In 1980, two policy scientists—Jack Knott and Aaron Wildavsky—published an article entitled “If dissemination is the solution, what is the problem?” (

1). The article thoughtfully critiqued the idea that disseminating research findings to policy makers was a panacea to social problems, a notion that was gaining acceptance at the time. A central tenet of Knott and Wildavsky’s argument was that the problem that dissemination sought to solve was often ill defined and that blindly disseminating evidence without considering the diverse characteristics of policy makers and the contexts in which they make decisions was ineffective and potentially counterproductive.

Although dissemination is by no means a silver bullet to challenges related to evidence-informed policy making (

2,

3), we argue that effective knowledge translation is part of a solution to an important problem in the arena of children’s mental health services research. The United States is in the midst of a children’s mental health crisis, with historically steep increases in rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide (

4–

7). Many policy makers are aware of the crisis, and most, if not all, want children to be mentally healthy and to flourish. And yet they often do not develop or support the policies that would contribute to this goal, because they are unaware of, or uncompelled by, evidence produced by children’s mental health services research. Evidence about what treatments work, the effects of neurodevelopment on children’s functioning, and the social determinants of children’s mental health is generally not communicated in ways that reach policy makers, are responsive to their information preferences, resonate with their worldview, or reflect the contexts in which they operate.

As a consequence of the ineffective translation of children’s mental health research, the policy and funding environment hinders the reach, fidelity, and sustainment of evidence-based mental health services for children and their families, as well as social and economic interventions that contribute to youths’ mental wellness (

8–

10). For example, state mental health agency investments in evidence-based treatments are in decline (

11), only 29 states have a definition of “evidence” to inform mental health policy and program decisions, and only 16 of these definitions have multiple tiers of evidence (

12). Policies that increase access to children’s mental services are underutilized (

13), and as a result, approximately half of children who need mental health services do not receive them—in some states the proportion not receiving these services is greater than 70% (

14).

Dissemination Science: Not a Panacea but Potentially Useful

Dissemination science—defined by the National Institutes of Health as the “scientific study of targeted distribution of information and intervention materials to a specific public health or clinical practice audience” (

15) (PAR-19–274) —can generate information to enhance the translation of children’s mental health services research. However, relatively little dissemination research in the United States has focused on public policy makers (

16), and even less has explicitly focused on mental health (

17,

18), let alone on children’s mental health. Successful policy maker–focused dissemination strategies are presumably different for mental health than for physical health because mental illness stigma is pervasive (

19–

22) and public willingness to allocate financial resources for mental health services is lower than for physical health services (

23,

24).

Additional complexities make effective policy maker–focused dissemination even more critical for children’s mental health issues. A first example is the paradox in children’s mental health whereby many children with serious need are not diagnosed or treated (

9) while some mental health conditions (e.g., attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) (

25) are overdiagnosed and some medications (e.g., antipsychotics) (

26) are over prescribed. A second complexity is the need to consider parents and family members in treatment and not just the individual child. Third, a wide range of public sector agencies interface with children’s mental health issues (e.g., education, child welfare, Medicaid, and juvenile justice), but few policy makers in these agencies have specialized knowledge about children’s mental health.

In the absence of empirical guidance to help children’s mental health services researchers and advocates effectively disseminate evidence to policy makers, the designs of dissemination strategies are typically based on anecdote, not data. As a consequence, evidence does not sufficiently reach, educate, or inform policy makers. The aim of this article is to provide guidance for researchers, advocates, and organizations who wish to use dissemination strategies to accelerate the policy impact of evidence produced by children’s mental health services research. To achieve this, we synthesize research about evidence-informed policy making, including recent studies about the dissemination of research on mental health and substance use (i.e., behavioral health) to state policy makers. The article builds on prior reviews of barriers to and facilitators of evidence-informed policy making (

2,

3) by extending findings to the specific area of children’s mental health. The article is also sensitive to critiques of the literature on evidence-informed policy making (

27–

29); we approach policy maker–focused dissemination as a challenge of political persuasion, not only a challenge of technical communication.

Several parameters should be noted. The article does not provide suggestions regarding specific evidence-supported polices related to children’s mental health that should be the focus of dissemination strategies, because such suggestions are provided in other reviews (

9,

13,

30,

31). The article also does not discuss barriers related to fundamental differences between researchers and policy makers (e.g., different incentive structures and different thresholds for accepting scientific uncertainty) (

3), because these barriers, and interventions to address them, are not specific to children’s mental health. Finally, the focus of the article is limited to dissemination strategies that

push mental health research findings to policy makers as opposed to complementary strategies that encourage the

pull of research findings by policy makers (

32).

Review of Relevant Research

This article draws heavily on findings from studies conducted as part of a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)–funded R21 project focused on developing the evidence base to inform the dissemination of mental health research to state policy makers (

18,

33–

37). The project involved surveys of two types of policy makers: state legislators and state mental health agency directors and senior staff (i.e., SMHA officials). In short, the state legislator survey was multimodal (Web based, regular mail, and telephone) and completed by 475 legislators, with at least one legislator from every legislature completing the survey. The response rate was 16.4%, which is higher than the response rates of other recent surveys of state legislators (

38–

40). Nonresponse weights were calculated and applied to adjust for differences between respondents and nonrespondents in terms of political party, gender, and geographic region. The SMHA official survey was Web based, limited to one senior official per state, and completed by 43 officials (response rate of 84%). Both surveys were conducted in 2017.

In response to feedback obtained from legislators and SMHA officials during the instrument-piloting phase of the project, the focus of the project was expanded to include substance use research in addition to mental health research. Thus project instruments used language of “mental health/substance use” and the term “behavioral health” is used in this article when referring to project findings. Complete details about the survey methods are available in the published study protocol (

18).

Table 1 summarizes differences between legislators and SMHA officials that are relevant to dissemination. It should also be noted that there is substantial heterogeneity among both legislators and SMHA officials when it comes to their knowledge about, and ability to address, children’s mental health issues. Among legislators, the most important dissemination audiences are likely legislators on key committees—such as health, education, and child welfare. Among SMHA officials, the most relevant policy makers are likely those who lead the children’s division (

41). Policy makers in other state agencies—such as Medicaid, child welfare, education, and juvenile justice—are also highly relevant dissemination audiences.

The research synthesis presented here integrates key findings from the NIMH-funded R21 (

33–

37) with findings from review articles focused on dissemination (

42,

43) and evidence-informed policy making (

2,

3,

17,

18,

27–

29,

44,

45), as well as our own experiences engaging in research and practice related to dissemination of mental health evidence to policy makers. The article focuses on three domains of policy maker–focused dissemination strategies (

Box 1). Drawing from Leeman and colleagues’ (

46) definition, we define dissemination strategies as the development and targeted distribution of messages and materials about research evidence pertaining to a specific issue or intervention. We first synthesize research about what evidence policy makers want when it comes to mental health issues and provide four recommendations for developing dissemination materials. Second, we discuss how strategic framing and message tailoring can increase the chances that evidence is persuasive to policy makers. Third, we highlight how intermediary organizations and initiatives that foster relationships between researchers and policy makers can help ensure that children’s mental health services research findings reach and are used by policy makers.

Being Responsive to Policy Makers’ Information Preferences

Although the amount of information that can be included in dissemination materials (e.g., a policy brief) is finite, the number of ways in which information can be presented is infinite. Thus the development of dissemination materials necessitates decisions about what information to include and how it should be packaged (

47). Drawing from the literature, we identify four key considerations for developing dissemination materials about children’s mental health for state policy makers and provide concrete guidance to aid the development of these materials. Readers may consult the article by Butler and Rodgers (

48) for a detailed description of the process of developing a policy brief about children’s mental health.

The value of economic evaluation data.

Developing budgets and allocating resources for mental health services are core activities of policy makers (

49). Therefore, policy makers want information about the economic impacts of mental health interventions. Among state legislators, 82% identified cost-effectiveness data as a “very important” feature of behavioral health evidence summaries, and 82% identified data about budget impact as “very important” (

33). Among SMHA officials, the proportions were 86% and 81%, respectively (

35). Cost-effectiveness data appear to be of particular importance to legislators, influencing the likelihood that they will use evidence summaries. Eighty percent of legislators indicated that they would be substantially more likely (rated as 4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale) to use a research brief if it presented data about cost-effectiveness of behavioral health treatments, rather than data on only the clinical effectiveness of the treatments. Among SMHA officials the proportion was 44%.

Although economic evaluation data are important to all legislators, such data are especially important to Republicans. When Republican and Democrat legislators were compared, a significantly higher proportion of Republicans identified data about cost-effectiveness (89% versus 76%) and budget impact (87% versus 77%) as “very important” features of behavioral health research (

33). Given that prior research has found that Republicans are generally less supportive than Democrats of spending on behavioral health services (

19,

49), demonstrating the economic benefits of investments in children’s mental health could be key to cultivating bipartisan support for policies that increase access to children’s behavioral health services.

Recommendation 1: Include economic evaluation data in dissemination materials. To produce mental health economic evaluation data, researchers might consult reviews that have estimated the cost-effectiveness of various mental illness prevention initiatives (

50), as well as published guidance for conducting economic evaluations of mental health interventions (

51). To obtain estimates related to specific evidence-based children’s mental health services, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy’s Benefit-Cost Results database offers useful information (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety among children, cost-benefit ratio of $24.18; Triple P [Positive Parenting Program], cost-benefit ratio of $7.66). Information about SMHA spending across different program areas is also publicly available, making it possible to produce and disseminate state budget–specific estimates of the economic impact of scaling up, scaling out, and deimplementing various children’s mental health interventions.

The local relevance of research findings.

State policy makers serve their constituents. Thus it is not surprising that studies show that policy makers want mental health research that is relevant to populations they represent (

52). This is especially true for SMHA directors, 93% of whom identified “relevance to residents in [their] state” as a “very important” feature of behavioral health research (

35). Thirty-seven percent of SMHA officials indicated that they would be substantially more likely to use a research brief if it presented data about behavioral health problems for different counties in their state, as opposed to their state in aggregate. Among legislators, 48% indicated that that they would be substantially more likely (rated as 4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale) to use a research brief if it presented these data among residents in their legislative district as opposed to their state in aggregate. Randomized controlled dissemination experiments in the United States and the United Kingdom have found that tailoring evidence summaries with data that correspond with the geographic area that a policy maker serves increases the likelihood of that individual’s use of and engagement with evidence (

53,

54).

Recommendation 2: Use state and local data. Using state and local data, as opposed to national data, about the magnitude of children’s mental health problems is one way to demonstrate the relevance of an issue to a policy maker’s constituents. State estimates of the prevalence of children’s mental health issues are readily available, such as those that can be derived from the National Survey on Children’s Health and other children’s mental health surveillance systems (

55). Local-level estimates are more challenging to produce. However, national surveillance efforts, such as the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, produce comparable local data (

56). Other studies have used small-area estimation techniques to present data at the level of U.S. congressional districts (

57,

58). These approaches could be used to generate estimates of the prevalence of child mental health issues at the level of the state legislative district.

State and local estimates of children’s mental health service availability can be created through data sets such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Mental Health Services and National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services surveys. Preparing and presenting maps using geographic information systems is a potentially effective way to demonstrate the local relevance of an issue to policy makers (

39), such as by depicting the distribution of facilities that offer evidence-based children’s mental health services in a geographic region. PolicyMap, a Web-based data mapping tool, allows for the boundaries of state legislative districts to be overlaid on data relevant to children’s mental health, such as the location of mental health treatment facilities and Head Start centers.

The importance of brevity.

Policy makers are very busy and typically underresourced (

3,

59). In many states, legislators have few or no staff—leaving it to them alone to sift through all the information they receive. For these reasons, policy makers value brevity in mental health evidence summaries. When presented with a list of 11 potential barriers to using behavioral health research and instructed to select “the three biggest barriers,” 43% of legislators and 33% of SMHA officials identified “lack of time” as a primary barrier to using behavioral health research in their work, and 28% and 30% of these policy makers, respectively, identified “lack of clear summary of research findings” as a primary barrier. Thus, not surprisingly, 82% of legislators and 81% of SMHA officials identified behavioral health research “being presented in a brief, concise way” as a “very important” feature of disseminated evidence (

33,

35). Not only do policy makers value brevity, research suggests that presenting too much evidence can be counterproductive. A randomized controlled dissemination experiment with policy makers’ in Denmark found that increasing the amount of information in an evidence summary did not produce beliefs that were aligned with the evidence and in some cases amplified beliefs that were counter to the evidence (

60).

Recommendation 3: Keep it brief.

The importance of evidence.

Studies suggest that details about empirical evidence should be explicitly emphasized, not glossed over, when communicating with legislators who prioritize behavioral health issues. These legislators are an important target audience, because they are typically the ones who draft and introduce children’s mental health bills and cultivate support for their passage (

61). A 2012 survey of state legislators found that those who prioritized behavioral health issues were significantly more likely than legislators who did not prioritize these issues to identify research evidence as a factor that influenced their policy priorities (

62). More recent data are consistent with these results. A 2017 survey found that state legislators who prioritized behavioral health issues were most strongly influenced by the extent to which a behavioral health bill was based on evidence when deciding whether to support it (

34).

Recommendation 4: Emphasize evidence for legislators who prioritize mental health issues. When developing evidence summaries for legislators who prioritize mental health issues (identified as such by a mental health advocacy organization or a track record of introducing mental health bills), researchers might consider adding details about the study design, p values, and confidence intervals—while also keeping the information presented concise.

Creating Dissemination Materials That Persuade Policy Makers

Framing.

The effectiveness of dissemination materials can potentially be enhanced by framing mental health evidence in ways that are persuasive to policy makers (

63). Framing involves selectively emphasizing certain aspects of an issue to alter specific opinions among a target audience (

64). Framing is particularly important when communicating with policy makers, because they rely heavily on heuristics (i.e., cognitive shortcuts) to make decisions, even more so than the general public (

65). For example, a report published by the FrameWorks Institute identified heuristics that the public and policy makers might use when thinking about children’s mental health, including the notions that “children can’t have mental health” because their emotional capacities are undeveloped and that mental illness is solely caused by genetic factors and thus cannot be prevented or treated (

66).

The use of strategic frames that account for heuristics can improve the effectiveness of dissemination materials and, at a minimum, reduce the risk that these materials will reinforce inaccurate ideas about children’s mental health. Frames can be created, for example, through choices about the evidence that is emphasized in dissemination materials and through the inclusion of brief narratives (i.e., stories) that illustrate how policy and system-level issues affect children with mental health conditions and their families (

67). Numerous experiments conducted with the general public have manipulated narratives to generate policy support for behavioral health issues (

68–

71), although none of this research has focused on children.

Framing decisions about children’s mental health issues can be informed by Corrigan and Watson’s (

49) conceptual model of how policy makers make decisions about the allocation of resources for mental health services. One of the four factors in the model is the extent to which policy makers perceive people as being responsible for their mental health problems. The more policy makers view the problems as being the result of factors beyond a person’s control, the more likely they are to allocate resources to help them (

72). Within the context of children’s mental health, an effective frame might emphasize the role of trauma, abuse, and neglect (factors beyond a child’s control) in the development of children’s mental health problems (

36). Such a frame could also emphasize the role of biogenetic risk factors for mental illness, but caution should be exercised when emphasizing this because such frames can potentially increase stigma toward people with mental illness (

73,

74).

All frames related to children’s mental health should be sensitive to the fact that stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about children with mental illness are common among the U.S. public and policy makers (

20–

22). Among state legislators, levels of stigma regarding mental illness are similar to those of the general public (

37). Frames related to children’s mental health should be sensitive to the fact that the public and policy makers’ concerns about mental illness are often linked to concerns about mass shootings (

19,

75), despite the reality that most people with mental illness are not at increased risk of perpetrating interpersonal violence (

76). Framing investments in children’s mental health as a strategy to prevent mass shootings could cultivate political support among some policy makers, but it could also produce and perpetuate stigma. For example, a public opinion experiment found that a frame that emphasized systems-level barriers to mental health treatment was as effective at increasing willingness to pay additional taxes for mental health system improvements as a frame that emphasized violence perpetration (

19). However, the frame emphasizing systems-level barriers did not produce mental illness stigma, whereas the violence perpetration frame did.

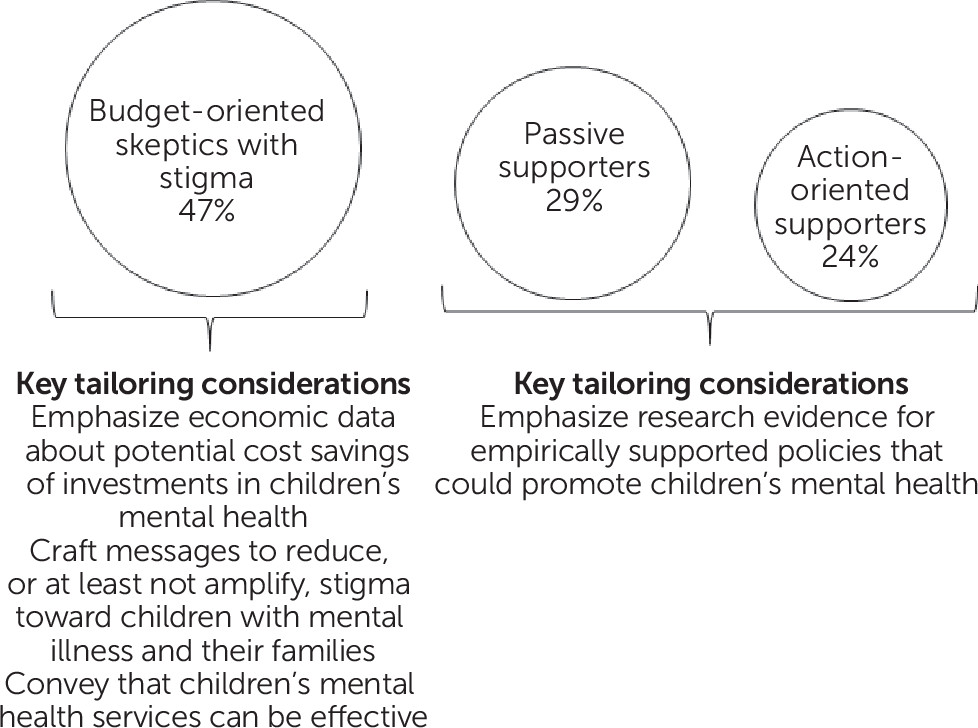

Message tailoring and audience segmentation.

Strategic frames can be most effective, and avoid undesirable messaging effects, when they are tailored for groups of policy makers with shared characteristics (

77). Audience segmentation analysis can help achieve this by identifying discrete groups of policy makers who are similar in terms of their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (

46,

78). An audience segmentation analysis identified three distinct groups of state legislators for whom tailored frames might be warranted when disseminating evidence about children’s mental health (

Figure 1). (

34) “Budget-oriented skeptics with stigma” (47% of legislators) are characterized as having high levels of mental illness stigma, believing that behavioral health treatments are not effective, being strongly influenced by budget considerations, and being ideologically conservative. In contrast, “action-oriented supporters” (24% of legislators) are characterized as perceiving behavioral health issues as policy priorities, introducing behavioral health bills, and being strongly influenced by the strength of evidence. Finally, “passive supporters” (29% of legislators) are characterized as having the most faith in the effectiveness of behavioral health treatments and the least mental illness stigma; however, this group is also characterized as being least likely to introduce behavioral health bills. Although the audience segmentation analysis was not specifically focused on children’s mental health, findings suggest that for legislators in the “budget-oriented skeptics with stigma” group, messages should be tailored to emphasize the cost-savings that can be produced by investments in children’s mental health (

50,

79,

80) and that messages should be carefully created so as not to amplify stigma toward children with mental illness and their families.

Ensuring That Evidence Reaches Policy Makers

The content and framing of dissemination materials matter little if the materials fail to reach policy makers. Thus it is important to consider the sources to which policy makers turn for mental health research and to disseminate evidence to those sources. Data suggest that the primary sources of behavioral health evidence vary between elected and administrative policy makers.

Among legislators, mental health advocacy organizations were cited as the primary source for behavioral health research (53%), whereas only 16% of SMHA officials turned to these organizations as a primary source (

33,

35). Professional organizations (e.g., National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors) are the primary source to which SMHA officials turned (77%), while only 38% of legislators turned to their respective professional organization (e.g., National Conference of State Legislatures) for behavioral health research. Universities were generally not cited by policy makers as a primary source for behavioral health research. Only 27% of legislators—and just 19% of Republicans—and 56% of SMHA officials reported turning to universities for this research.

Given that universities are major producers of children’s mental health research, initiatives that foster relationships between university researchers and policy makers could increase the chances that evidence reaches and is used by policy makers. Facilitating social interactions and interorganizational linkages has been identified as an important aspect of such strategies (

81,

82). Recent research also has found that the presence of state-focused, university-affiliated research and evaluation centers were robust predictors of state-level funding and policy supports for evidence-based mental health services (

83).

At the state level, the family impact seminar model is one approach to connecting children’s mental health researchers and policy makers that has demonstrated promising results (

84). The William T. Grant Foundation has also produced guidance about models of research-practice-policy partnerships that can improve the dissemination and use of research evidence in the areas of child mental health and welfare (

85). At the federal level, the research-to-policy collaboration model, which involves legislative needs assessments and a rapid-response researcher network, is an example of a model that shows promise at increasing the uptake of findings from prevention science (

86). Outside the United States, intermediary organizations in Canada are supported by government funds to help facilitate connections between mental health researchers and policy makers (

87). In Australia, the Supporting Policy In health with evidence from Research: an Intervention Trial (SPIRIT), which included the facilitation of interactions between researchers and policy makers, found that the intervention improved policy makers’ perceptions of and capacity for research use (

88). With appropriate funding or other incentive structures, such models could be adapted for the U.S. context and the area of children’s mental health.

Limitations and Future Directions

As noted above, the focus of this article is limited to dissemination strategies that push children’s mental health research findings to policy makers. There are many complementary strategies that may also facilitate the translation of children’s mental health research into policy, such as those that encourage the pull of research findings by policy makers, cultivate public demand for evidence-supported children’s mental health policies, and foster coalition building around children’s mental health issues. Research and scholarship that provide concrete guidance about how to carry out these strategies would benefit the field.

The data presented in this article about the dissemination preferences of administrative policy makers are limited to those in state mental health agencies and policy makers across a range of executive branch agencies who make decisions that affect children’s mental health. There would be value in future research that characterizes these policy makers’ preferences for, and practices of using, children’s mental health research.

There is also a need for research that sheds light on the dynamics of children’s mental health policy-making processes. Such studies can generate insights that could enhance dissemination strategies, such as by elucidating the factors that open a “policy window” for children’s mental health and identifying the ideal times in policy cycles to disseminate evidence. Although some prior work has been conducted in this area (

52,

89,

90), there could be benefit to future research with a specific eye toward implications for dissemination. Finally, there is a need for experimental research that tests the effects of different dissemination strategies on policy makers’ engagement with and uses of children’s mental health research, knowledge and attitudes about children’s mental health issues, and policy-making behaviors (e.g., volume and content of children’s mental health policy proposals).

Conclusions

Like most issues in the realm of children’s mental health, the problem that policy maker–focused dissemination seeks to solve is extremely complex. It would be naive to think that dissemination strategies, even if designed and executed with absolute precision, would transform the policy environment. That said, the effectiveness of dissemination strategies can certainly be enhanced. Specifically, policy maker–focused dissemination strategies can be improved by using empirical data to inform decisions about what information is included in dissemination materials, how evidence is framed for different audiences, and the entities that deliver dissemination materials. Dissemination science can generate these data and help accelerate the policy impact of children’s mental health services research.