Factors Affecting Mental Health Professionals’ Sharing of Their Lived Experience in the Workplace: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

HIGHLIGHTS

Methods

Search Strategy

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

| Study and year | Design | Participants | Data collection | Data analysis | Overall findings | Key limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adame, 2011 (20) | Qualitative | 5 MHPs (psychologists) with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Semistructured interviews | Holistic content analysis | MHPs with lived experience served as role models in breaking down the ‘‘us and them’’ divide and supporting continuum models of emotional distress. | Study design and participants were not well suited for the stated purpose (i.e., to facilitate dialogue). Data saturation was not addressed with respect to the small sample. |

| Boyd et al., 2016 (11) | Mixed methods | 77 MHPs (psychologists, social workers, nurses, and “other”) with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Survey with qualitative data | Descriptive statistics, thematic analysis | On average, participants had disclosed to 16% of their colleagues, and one-third had not disclosed to any of their colleagues. Participants reported their lived experience as an asset and identified both enabling and constraining factors for disclosure. | Potential for sampling bias existed; however, this was addressed by authors. |

| Byrne et al., 2019, manuscript in review | Qualitative | 132 MHPs, including peer workers | Focus groups and interviews | Grounded theory | Promotion of disclosure for MHPs with lived experience did not automatically occur as a result of peer employment. Enabling factors included peer-designed and peer-delivered training and supervisors sharing their own challenges. | Differences in data collected in interviews and focus groups were not reported. |

| Cain, 2000 (50) | Qualitative | 10 MHPs (social workers, psychologists, and a psychiatrist) with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Participants reported reluctance to disclose to colleagues because of experiences of stigma and discrimination. Nondisclosure had negative impacts on MHPs with lived experience and on service quality and MHPs’ understanding of emotional distress. | This is the earliest peer-reviewed study found for review. The description of procedural and analytical rigor to determine trustworthiness is inadequate. |

| Cvetovac and Adame, 2017 (51) | Qualitative | 11 MHPs with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Discursive analysis | Holistic content analysis | Themes reported included “hiding and revealing psychological wounds,” with “need to hide” competing with a “desire to open up.” | Data saturation was not addressed with respect to the small sample. The description of participants’ work settings is inadequate to assess transferability. |

| Godfredsen, 2005 (52) | Mixed methods | 152 MHPs (psychologists, psychiatrists, and students of mental health professions) with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Survey with qualitative data | Descriptive statistics, thematic analysis | Psychologists reported fewer fears and negative experiences with regard to disclosure, compared with psychiatrists. Women were more likely to disclose to colleagues and supervisors. Themes included ongoing experiences of actual discrimination and reactions from colleagues, the usefulness of lived experience in clinical work, balancing the rights of MHPs with lived experience with standards for quality of care, and role conflict and internalized stigma. | Conclusions regarding the high prevalence of lived experience among MHPs were inappropriate, given the potential for selection bias in the sample. The description of analysis of qualitative data is inadequate. Potentially identifying and libelous raw data were published in an appendix. |

| Harris et al., 2016 (15) | Quantitative | 101 MHPs (psychologists, nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, and “other”) in non–peer-designated roles | Survey | Statistical analysis | Lived experience, knowledge of the recovery model, and work engagement were all associated with lower levels of disidentification with service users. Knowledge of the recovery model and work engagement were associated with lower levels of disidentification with MHPs with lived experience. | The low response rate may have indicated sampling bias in reported prevalence of mental health challenges and in findings with regard to differences between MHPs with and without lived experience. |

| Harris et al., 2019 (19) | Quantitative | 101 MHPs (psychologists, nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, and “other”) in non–peer-designated roles | Pre and post measures | Statistical analysis | There was greater evidence of reduction in stigmatized beliefs among MHPs when education was followed by continuous contact with an MHP with lived experience. | The effect of contact-based education intervention was not isolated. Lack of time-series analysis limited statistical power. |

| Infranco, 2013 (53) | Mixed methods | 74 MHPs (social workers, counselors, psychologists, and “other”) in non–peer-designated roles | Self-study, survey, semistructured interviews | Descriptive statistics, narrative analysis | Themes included barriers encountered as a recovered professional, the benefits of experiential knowledge and being recovered, and the use of honesty as a means of advocacy and giving hope. | Data saturation was not addressed with respect to the small number of interview participants (N=2). |

| Johnston et al., 2005 (54) | Mixed methods | 202 participants, including MHPs, service users, and caregivers | Survey | Statistical analysis | Among all participants, 81.7% thought it was appropriate for MHPs with a history of eating disorders to work in the field of eating disorders treatment. MHPs without such a history were less likely than service users and caregivers to think it appropriate; 9.9% of all respondents felt that it would be appropriate for an MHP who currently suffered with an eating disorder. | The description of discipline and work setting of MHPs is inadequate. The study appears to conflate disclosure to colleagues and disclosure to service users. The study design represents a reductive approach to a complex issue. |

| Joyce et al., 2009 (55) | Qualitative | 29 nurses with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles, working in general and mental health settings | Semistructured interviews | Discourse analysis, ethnography | An overall theme emerged of support and trust, with four subthemes: declaring mental illness, collegial support, managerial support, and enhancing support. Most participants described constraining factors for sharing of lived experience. | It is unclear whether differences existed in experiences of nurses working in mental health and general settings. The description of procedural and analytical rigor to determine trustworthiness is inadequate. |

| Joyce et al., 2012 (40) | Qualitative | 14 nurses without lived experience, working in general and mental health settings | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis independently coded by two team members | Most participants were sensitive to the needs of colleagues who were affected by emotional distress and were willing to support them. However, many nurses were unaware and lacked understanding of the issues and how to deal with these issues in the workplace setting. | Data saturation was not addressed with respect to the small sample. It is unclear whether differences existed in narratives of nurses working in mental health and general settings. Conclusions reflected limitations in the interpretive paradigm. |

| Kidd and Finlayson, 2010 (56) | Qualitative | 19 nurses with lived experience, including 9 working in mental health settings | Narrative writing | Collective autoethnography | Nurses described experiences of stigma, discrimination, and bullying in the workplace that were linked to intolerance of vulnerability. Symbolic violence in the form of bystander inaction during instances of bullying was also noted. Nondisclosure of lived experience or leaving the profession of nursing was linked to internalized stigma. However, some reported that their lived experience was an asset to their practice. | It is unclear whether differences existed in narratives of nurses working in mental health and in general settings. The authors advocated for a “radical change” in nursing culture; however, the approach to the topic and the language used were somewhat pathologizing. |

| Kottsieper and Kundra, 2017 (57) | Mixed methods | 69 MHPs (mostly social workers and counselors) with lived experience | Survey | Descriptive statistics | Participants reported overall positive responses to disclosure to colleagues and supervisors, including support and mutual disclosure. A small group reported experiences of discrimination and social distancing in response to disclosure. | The brief report was published online, and peer review was not reported. The survey was not well described (i.e., closed versus open questions). Exclusion of other disciplines limited transferability of findings outside the United States. The small sample size was not addressed. |

| Lindow and Rooke-Matthews, 1998 (58) | Qualitative | 36 MHPs (social workers, nurses, and “other”) with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Interviews and workshop | Not described | Participants reported discrimination from employers and colleagues. Whether or not to be open about past mental health treatment was a dilemma during recruitment and while employed. | The study is 21 years old and was published online as a brief report, with peer review not reported. The professional background of the “other” group is unclear, as are differences between staff in paid and unpaid roles. The description of procedural and analytical rigor to determine trustworthiness is inadequate. |

| Morgan and Lawson, 2015 (32) | Qualitative | About 27 participants, including MHPs in non–peer-designated roles and service users | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Enabling factors identified included supportive team and organizational cultures, role models, and supportive human resources policies. | The study is not formal research; however, it demonstrated sufficient attention to procedural and analytical rigor for findings to be considered trustworthy. |

| Peterson, 2017 (59) | Qualitative | 1 MHP (nurse) with lived experience in a non–peer-designated role | Journaling | Autoethnography | Constraining factors identified included fear of stigma, abuse of power in managerial relationships, experiences of discrimination and surveillance in return to work practices, and mandatory reporting to professional bodies. | The description of procedural and analytical rigor in creation and analysis of the narrative is inadequate. |

| Richards et al., 2016 (21) | Qualitative | 10 MHPs with lived experience in peer-designated and non–peer-designated roles (art therapy, nursing, management, social work, peer work, psychology, occupational therapy, and psychiatry) | Semistructured interviews | Discourse analysis | Participants described both “unintegrated” and “integrated” identities. Positive identity discourses that integrated experiences as a service user and a professional drew on discourses of “personhood,” “insider activist,” “personal recovery,” “lived experience,” and “use of self.” | Data saturation was not addressed with respect to the small sample. The sample included staff in designated peer roles and trainees but did not differentiate in reporting of findings. |

| Tay et al., 2018 (60) | Quantitative | 678 MHPs (psychologists) in non–peer-designated roles | Survey with standardized measures | Statistical analysis | Two-thirds of participants identified as having lived experience. Perceived stigma regarding mental illness was higher than external and self-stigma. Intrapersonal factors that constrained disclosure included fears about negative consequences for self and career and shame. | The focus on disclosure for help seeking was somewhat reductive, considering the inclusion of stigma measures. |

| von Peter and Schulz, 2018 (61) | Qualitative | 1 MHP (psychiatrist) with lived experience in a non–peer-designated role | E-mails | Autoethnography | Examples are given of how the “us and them” divide is produced by implicit category work by MHPs, service users, and researchers. | The findings have limited transferability because it is unclear whether the first author works clinically. The description of procedural and analytical rigor is inadequate. |

| Waugh et al., 2017 (62) | Qualitative | 13 MHPs in non–peer-designated roles and 11 health professionals in other health fields | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Key themes included personal experiences and their effect in changing attitudes, perceived stigmatizing views of mental illness among other staff members, factors affecting one’s decision, attitudes toward disclosure, and support in the workplace after disclosure. The decision about disclosure of lived experience was carefully thought out, with advantages and disadvantages. Participants identified fear of stigma and discrimination from colleagues as constraining factors. | The reporting of findings did not specify which respondents had lived experience themselves. All MHPs were nurses, and thus the findings may not generalize to MHPs from other disciplines. |

| White et al., 2006 (26) | Quantitative | 370 MHPs (psychiatrists) | Survey | Statistical analysis | Overall, 13.8% would disclose a future mental illness to colleagues. Reasons for not disclosing were career implications (34.7%), professional integrity (27.5%), and stigma (22.4%). Those with lived experience were less likely to disclose a future mental illness and were more likely to cite stigma as the reason for this decision. | Questions asked of participants were limited to reasons for nondisclosure rather than reasons they might disclose. Concepts such as “stigma” and “professional integrity” were not operationally defined in the questionnaire. Responses to open questions were not reported. |

| Williams and Haverkamp, 2015 (63) | Qualitative | 11 MHPs (social workers, counselors, and psychologists) with lived experience in non–peer-designated roles | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes included boundary issues; the wellness of MHPs with lived experience, helpfulness of lived experience, and openness regarding lived experience. There was a lack of perceived interpersonal safety in some settings, resulting in isolation, discouraging consultation and supervision, and inhibiting development of self-awareness and identity integration of lived experience. | The sample was small. Conclusions were limited by an ethical framework locating disclosure of lived experience as an individual issue. |

Data Analysis

Results

Description of Included Studies

| Factor | N studies | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Enabling environmental factors | 20 | 11, 15, 19–21, 32, 40, 50–55, 57–59, 61–63; Byrne et al. |

| Supportive workplace culture | 14 | 11, 15, 19, 32, 40, 51–53, 55, 57–59, 62; Byrne et al. |

| Supportive management practices | 9 | 11, 32, 40, 53, 55, 57, 58, 62; Byrne et al. |

| Lived experience regarded as an asset | 9 | 15, 19, 21, 32, 50, 53, 54, 63; Byrne et al. |

| Guidance and support to share and use lived experience | 9 | 11, 32, 50, 53, 57, 61, 63; Byrne et al. |

| Continuum model of mental distress | 7 | 11, 20, 21, 32, 55, 61; Byrne et al. |

| Human resource practices | 6 | 11, 19, 32, 50, 57, 58 |

| Leadership championing of disclosure | 5 | 11, 19, 32, 57; Byrne et al. |

| Constraining environmental factors | 21 | 11, 15, 19–21, 32, 40, 50–59, 61–63; Byrne et al. |

| Allowed ways of being a professional | 17 | 20, 21, 32, 40, 50, 52–59, 61, 63 Byrne et al. |

| Culture of nondisclosure | 11 | 11, 19–21, 32, 40, 53, 55, 57, 58, 63 |

| Discrimination | 9 | 11, 21, 40, 53, 55, 57–59, 62 |

| “Us and them” dichotomy | 7 | 19–21, 51, 53, 61; Byrne et al. |

| Lived experience as a liability | 7 | 21, 40, 53, 54, 58, 59, 63 |

| Unsupportive management practices | 5 | 40, 55, 59, 62; Byrne et al. |

| Intrapersonal factors | 20 | 11, 20, 21, 32, 50–63 |

| Safety and fear | 16 | 11, 21, 26, 32, 50–53, 55, 57–60, 62, 63; Byrne et al. |

| Pride and shame | 15 | 11, 19–21, 32, 50–56, 60, 61, 63 |

| Negotiating hybrid identities | 12 | 11, 21, 32, 51–53, 56–58, 60, 61; Byrne et al. |

| Current state of distress or well being | 10 | 11, 51–55, 59, 60, 62; Byrne et al. |

| Insider activism | 9 | 11, 20, 21, 32, 52, 53, 57, 58, 63 |

| Female gender | 1 | 52 |

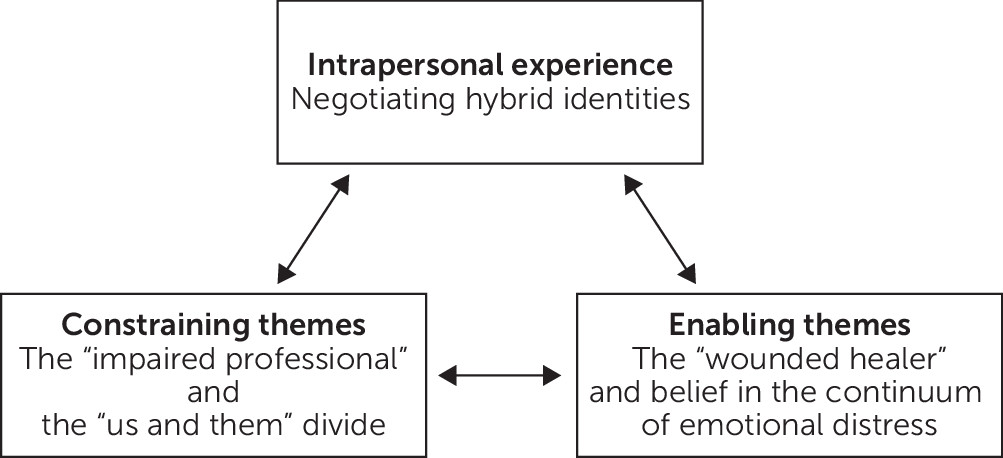

Constraining Themes: The “Impaired Professional”

Constraining Themes: The “Us and Them” Divide

Enabling Themes: The “Wounded Healer”

Enabling Themes: Belief in the Continuum of Emotional Distress

Intrapersonal Experiences: Negotiating Hybrid Identities

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 20.90 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Competing Interests

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).