It is estimated that in 2017, 46.6 million adults were living with mental illness in the United States (

1). Persons with mental illness frequently seek care in the emergency department (ED), with estimates indicating that one in eight ED visits are directly or indirectly related to mental health (

2). According to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 5.485 million ED visits in 2016 were for a primary psychiatric diagnosis (

3). The ED provider has several objectives when evaluating these patients: initially stabilizing the patient if unsafe behaviors exist, assessing whether a medical pathology could be playing a role in the presenting symptoms, determining disposition to either inpatient admission or discharge from the ED, and determining the appropriate admitting service (psychiatry vs. hospital medicine).

There has been debate about the benefits of routine screening labs. Although the literature suggests some utility of this practice (

6–

14), most recent studies have shown that the vast majority of abnormalities detected by laboratory tests were for patients for whom a test was ordered after a clinical history review or physical exam. These studies concluded that ordering routine screening laboratory tests has little to no value (

15–

26). Other studies have reported utility of more nuanced ordering of screening labs for certain patient populations, such as elderly persons and patients with no previous psychiatric history (

27–

29). Ultimately, several position statements from professional groups (e.g., the American College of Emergency Physicians and American Association for Emergency Psychiatry) have spoken out against ordering routine lab tests (

30–

32). Although this position is generally strongly supported by emergency medicine practitioners, the psychiatry community has been much slower in endorsing it (

33). Most hospitals still have guidelines that require mandatory screening lab tests for psychiatric admission (

34).

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

This study was conducted at a large tertiary care hospital with a 100-bed adult inpatient psychiatric unit. All pediatric and geriatric patients needing psychiatric admission are transferred elsewhere. Approximately 88,000 patients per year arrive in our ED, of whom roughly 3,500 are admitted to the inpatient psychiatry service. Within the ED, an 11-room care area is dedicated for patients with mental health complaints, staffed by emergency physicians, physician assistants, residents, and social workers. On April 16, 2018, a change in policy was made from routine ordering of laboratory tests to ordering based on individual patient evaluations. Data were obtained for a 4-month period before the change (December 15, 2017–April 15, 2018) and a 4-month period starting 1 month after the change (May 16–September 16, 2018). This allowed 1 month for the new process to become routine practice, allowing for more representative data.

Data from all patients admitted from the ED to the inpatient psychiatric service were included. This cohort included those who arrived with a clear primary mental health complaint, as well as those who may have been initially seen for injuries, ingestions, drug use, alcohol intoxication, or medical symptoms and who were eventually medically cleared and found to meet criteria for psychiatric admission.

This project was reviewed by the Regions Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB), which judged it to be a quality improvement project and not to require ongoing IRB oversight.

Interventions

Before the change in policy, the hospital’s standard admission order set required for inpatient psychiatric admission included orders for complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, basic urine drug screen, and urine pregnancy test when applicable. After the policy change, these lab tests were no longer required and were ordered at the discretion of the ED provider or at the request of the admitting psychiatric service.

Measurements

All data elements for this study were retrospectively obtained from electronic medical record data, and billing and coding data were retrieved via an automated data query. The data sets were created by hospital analysts who were blinded to the study hypothesis. Data included patient demographic characteristics, arrival information, diagnoses, common medical comorbid conditions, and common lab orders, as well as orders for electrocardiograms or noncontrast computed tomography head scans. Costs for lab and other diagnostic tests were determined according to the charge master of the hospital during the study period. We also collected orders for consultations and patient transfers to hospital medicine service or the intensive care unit (ICU) service. Finally, we collected ED and inpatient length of stay (LOS).

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for this evaluation were the total number of lab tests ordered and total charges for these orders. The charged orders included any placed from patient arrival in the ED to patient discharge from the hospital. Secondary outcomes included the number of lab tests ordered during the ED and inpatient stays, cost of tests ordered during the ED and inpatient stays, ED and hospital LOSs, inpatient consultations for hospital medicine or specialty services, transfer to hospital medicine, transfer to ICU, and death.

Analysis

Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, means and SDs, and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), were generated as appropriate for variables of interest. Because the data were nonnormally distributed, all continuous variables were described by median and IQR, except when this was not informative (i.e., a median of 0; see below). Chi-square tests were used to statistically assess differences among categorical variables between the pre and post groups. For continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the pre and post groups with a 95% confidence level. For a given individual lab test, we determined whether it was ordered for a patient. For total cost analysis, we included all lab tests ordered, including multiples of the same test if applicable. For example, a patient who was admitted with slight anemia that was monitored with several CBC orders over several days to assess for stability would be counted as a single order for CBC in the lab order analysis but as multiple lab orders in the cost and total labs analysis. We chose this analysis to avoid any skewing that would happen because of inpatients with multiple similar lab orders during their stays.

Results

Data from 1,910 patients were included in the analysis (886 in the preimplementation cohort and 1,024 in the postimplementation cohort), of whom 1,028 (54%) were male. Patient characteristics are shown in

Table 1. Patients in the postimplementation cohort were slightly older and had a higher incidence of coronary artery disease and hypertension as comorbid conditions, but these differences were not clinically relevant. The two groups did not clinically significantly differ in admitting diagnoses. All other demographic variables were balanced between the two groups.

Primary Outcome

Because the number of lab tests and hospital charges were not normally distributed, results are presented as medians with IQRs (

Table 2). The median number of total lab tests ordered in the ED pre- to postimplementation decreased from three to one (p<0.001). The median number of lab tests ordered in the hospital was identical between the two groups (0), likely because no tests were ordered for a large number of patients, skewing the data toward the median of zero. The mean±SD number of lab tests ordered in the hospital, however, increased from pre- to postimplementation, from 0.94±3.00 to 1.47±2.81 (p<0.001). The total median number of tests ordered during the hospital stay (ED arrival to hospital discharge) decreased from three to two (p<0.001).

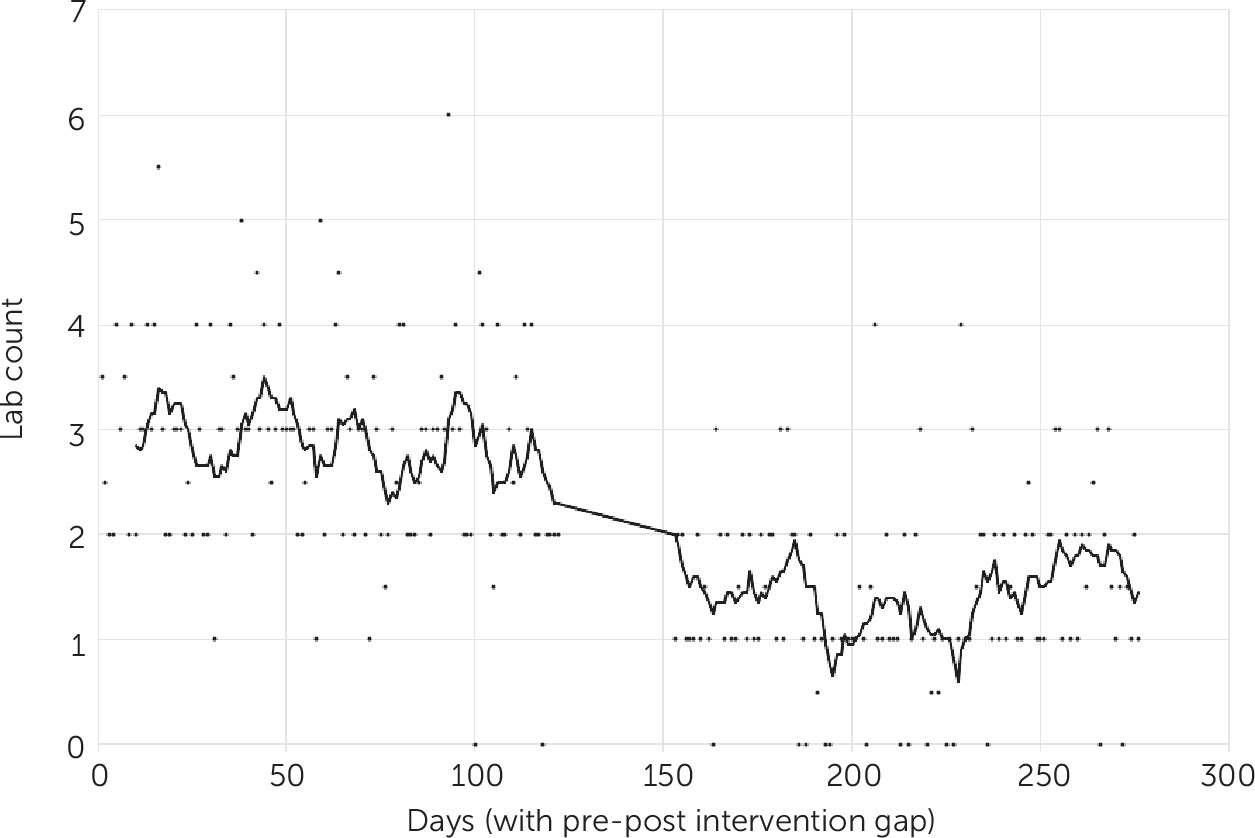

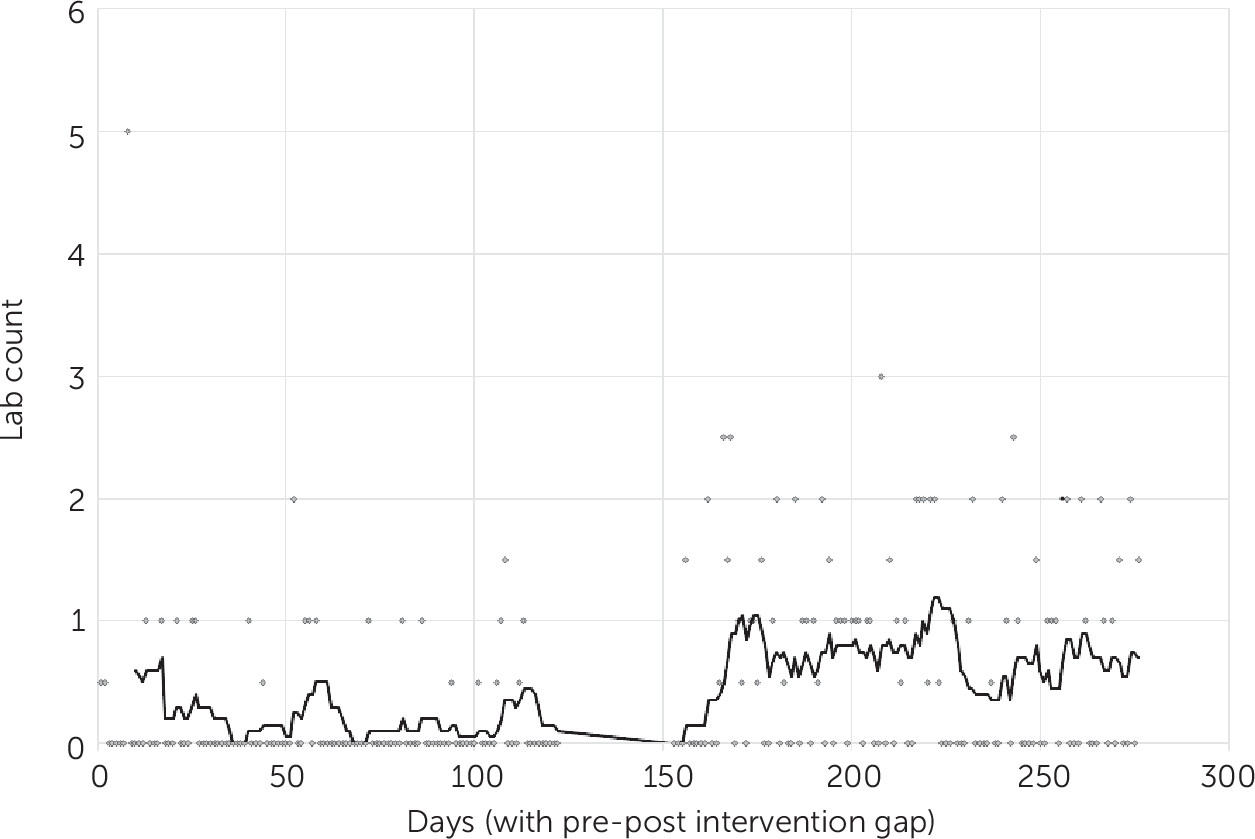

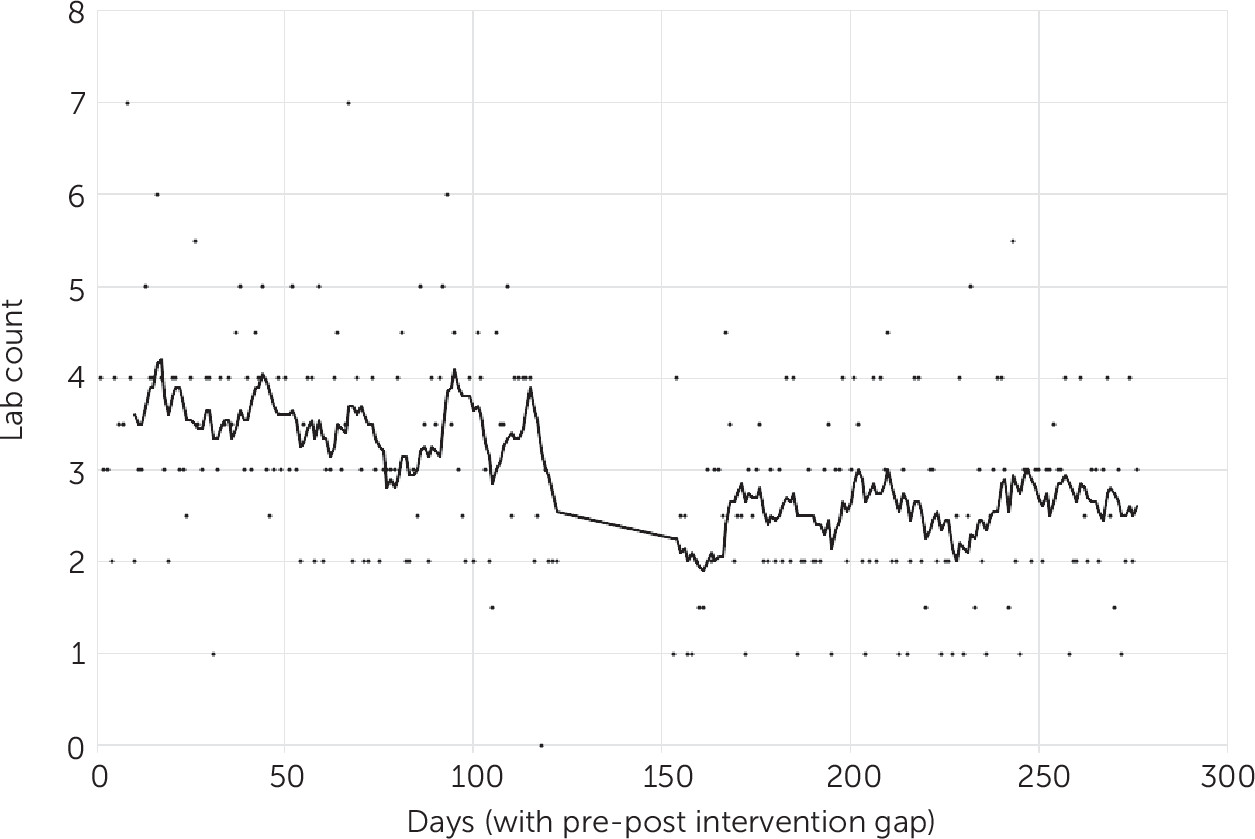

The daily median number of lab orders during hospitalization are shown in

Figures 1,

2, and

3. The number of patients with no lab tests ordered at any point during the hospital stay increased from 82 (9%) to 206 (20%) (p<0.001). The number of patients with no tests requiring a blood draw increased from 194 (22%) to 411 (40%) (p<0.001).

The most notable pre- to postimplementation decreases in specific lab orders in the ED included the CBC (70% to 25%, p<0.001), chemistry panel (72% to 30%, p<0.001), urinalysis (27% to 15%, p<0.001), and urine drug screen (63% to 54%, p<0.001). The ordering of most of these tests increased in the inpatient psychiatry unit, except for the urinalysis, which did not change significantly.

The total median ED lab charges per patient decreased from $405 to $93 (p<0.001). The total median inpatient lab charges were $0 before and after the change, and the total mean inpatient lab charges per patient increased from $139.59±$447.81 to $212.78±$400.91 (p<0.001). The median total lab charges per patient during the hospital stay (ED arrival to hospital discharge) decreased from $445 to $312 (p<0.001), representing a cost saving of $133 per patient. When multiplied by our postintervention patient cohort of 1,024 patients, this represents total savings of $136,192.

The mean LOS in the ED decreased from 810.0 to 477.5 minutes (p<0.001), and the mean LOS in the hospital from 113.9 to 97.9 hours (p=0.003). The percentage of consultations placed by the psychiatry service for inpatient medical or other consultation services did not change after the policy change. There were 171 consultations (19%) for inpatient medicine before the change and 206 consultations (20%) after the change. Moreover, no change was detected in the percentage of consultations with other services, with 29 (3%) consultations before and 38 (4%) after the policy change. The number of patients transferred to the hospital medicine service was 8 (1%) before the change and 13 (1%) after it. No patients in either cohort were transferred to the ICU or died during the hospital stay.

Discussion

The psychiatry community has historically been reluctant to substantially change the practice of requiring routine screening lab tests for psychiatric admission. The reasons for this are likely multifactorial. The clinical presentation of possible mental health crises can mimic many other medical emergencies. Inpatient psychiatric hospitals typically have fewer resources to care for patients with acute medical conditions. Likewise, psychiatrists have limited training and experience caring for nonpsychiatric illnesses. Arguments against the indiscriminate ordering of routine lab tests do not deny their utility. Rather, the focus is on placing orders for appropriately selected patients—those with abnormal vital signs, abnormal findings on a physical exam, or concerns raised after review of the patient’s medical history.

To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of a real-world change in practice in which routine lab orders are no longer required for admitted psychiatry patients. We observed a number of benefits without any obvious deleterious effects. These benefits included fewer blood tests, which equated to fewer blood draws, as evidenced by the increased number of patients with no blood lab orders; lower cost of care; and decreased LOS in both the ED and the hospital. Together, these improvements represent the three dimensions of the “triple aim” of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (

36). Another patient-centered benefit of not utilizing routine screening labs before admission is a reduced risk for escalating agitation by forcing a patient to undergo an invasive blood draw. This reduces the risk of harm to the patient and the care team and has the potential to improve ED throughput of patients. Finally, the decrease in urinalysis ordering may have led to fewer false-positive diagnoses of urinary tract infections and fewer antibiotic prescriptions.

The large decrease in lab ordering in the ED was somewhat offset by a less pronounced increase in lab ordering of nearly all the same lab tests during the inpatient stay. However, the total overall lab ordering decreased significantly. Perhaps most important, the percentage of patients with no lab orders increased from 9% to 20%, and the proportion of patients with no blood lab orders increased from 22% to 40%. In our cohort, this represents a substantial number of patients who did not have to undergo invasive and painful needle pokes.

The least pronounced decrease in lab ordering was the order for a urine drug screen. This could suggest a utility of this test—perhaps to help with evaluating specific symptoms or to help with disposition of patients with possible chemical dependence. Ordering of other tests, such as liver panel, troponin level, and alcohol level, was similar before and after the policy change both in the ED and the inpatient ward. This similarity suggests that the policy change did not necessarily affect the ordering of tests that were tailored more specifically to individual patients.

The decreased LOS in the ED was to be expected, given a decrease in time spent waiting for lab samples to be obtained from the patient and processed in the lab. Of note, inpatient LOS also decreased. These decreases in LOS certainly translated to improved timeliness of patient care. Increased throughput indicates increased capacity to care for patients, which likely translated to decreased cost for individual patients and possibly increased revenue for the hospital.

Of note, lab tests ordered in the ED were at the discretion of the provider. However, the accepting psychiatry provider could request specific lab tests before accepting the patient. This collaborative aspect of patient care did not change after the policy change.

Several factors may explain why the rate of lab ordering for the required admission lab tests (CBC, chemistry panel, urinalysis, urine pregnancy test, and urine drug screen) before the policy change was not 100%, as might be expected when these tests were part of the routine order set. If patients had tests ordered within the 6 months before admission, repeat lab test orders were not required. If a patient could not urinate before being transferred to inpatient care, the urinalysis, urine pregnancy test, and urine drug screen were deferred to inpatient care. In addition, patients frequently refuse lab tests, which, if deemed that the results are unlikely to be abnormal, are also often deferred to inpatient care.

A strength of the study was that it was a simple before-and-after study at a single institution. During the study period, no other major policy changes were implemented that would likely have affected the outcomes examined here. This provided a unique opportunity to evaluate behavior change in a straightforward manner. Second, all the data were obtained through automated retrieval from an administrative database. Because of this, the study could be completed in a timely manner, with little risk for introducing bias into the data abstraction process. The data set included a large number of patients over a 9-month period, allowing inclusion of patients with a multitude of psychiatric diagnoses. Finally, although this was a retrospective review, the data set was robust. It was generated by several analysts with routine experience in conducting similar electronic medical record queries.

Previously, hospitals have been reluctant to adopt the policy change that we have described here. With the current findings supporting these changes, perhaps more hospitals can move from one-size-fits-all policies to more nuanced policies of tailored lab ordering.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. A notable limitation was that the study was conducted at a busy tertiary care center, with extensive experience caring for patients with mental illness and a large psychiatry inpatient unit. Moreover, experienced emergency physicians, physician assistants, and social workers examined these patients. These factors may limit the generalizability to other facilities with fewer resources. Additionally, it is possible that patients undergoing routine screening labs in the cohort before the policy change would have had notable lab test abnormalities that precluded their admission to the psychiatry service. In theory, this would have led to a more carefully screened patient group and would have led to fewer transfers to the hospital medicine service during that period. Because this outcome was not observed, it is unlikely that this scenario affected the composition of our patient cohort.

Previous research has shown a reduction in test ordering after various initiatives; however, sustainability of the reduced ordering has not been studied as thoroughly (

37). Future investigations could evaluate whether similar policy changes lead to enduring changes in practice. The policy change described here included all patients admitted to inpatient psychiatry, regardless of age, comorbid conditions, and diagnoses. We did not evaluate the utility of lab ordering in specific patient subgroups; future research and policy changes may consider explicit recommendations for higher-risk patient groups, such as older patients or patients with substance use disorders.