American military veterans and service members face an elevated risk for trauma exposure and psychiatric illness. An estimated 21%−41% of veterans returning from recent conflicts have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and 7%−15% have syndromal depression (

1). The combination of PTSD and major depression is particularly difficult to treat. A compounding risk factor for poor outcomes among veterans is their reporting of adverse experiences before and after deployment (

2,

3). Beyond the personal ramifications of PTSD and depression for veterans and service members, these disorders can affect military families through marital and parental dissatisfaction, disrupted child-parent relationships, caregiver burden, and domestic violence (

4,

5). These issues, in addition to elevated rates of trauma exposure unrelated to military service among military spouses, help account for high rates of PTSD and depression among military spouses, family members, and caregivers (

6–

8). These manifold problems affecting veterans, service members, and military families require responsive interventions that can alleviate PTSD and depressive symptoms. This report describes an open trial of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for treating military service members, veterans, and family members for PTSD with and without comorbid depressive disorder.

Available PTSD Treatment

Guidelines from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Department of Defense (DoD) primarily recommend exposure therapies for PTSD, including cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure (PE) (

9). Although research supporting exposure therapy is extensive (

10,

11), the limited range of available treatments for PTSD raises concerns. The very success of exposure therapies has resulted in insufficient study and clinical dissemination of other approaches. No treatment benefits everyone, and nonresponse and dropout occur even in the most robust interventions. Moreover, patients are more likely to experience improvement when given their preferred treatment (

12,

13). Many clinicians and patients avoid exposure-based interventions, which ask traumatized patients to confront their worst fears. Dropout rates can be high, generally exceeding 20% (

14,

15), and even though no direct comparison studies have been conducted, the outcomes of these interventions among veterans generally appear to be less favorable than among civilians (

16–

18). Hence, alternative treatments require investigation. Interventions targeting PTSD among military family members also need evaluation, because virtually no research has assessed mental health treatment for military family members despite well-recognized elevations in psychopathology among members of this group (

7).

IPT for PTSD

IPT, a nonexposure, non–cognitive-behavioral therapy approach, focuses on affect, life circumstances, and interpersonal relationships and on the interpersonal consequences of trauma, rather than on the trauma itself, distorted cognitions, or behavioral habituation (

19). IPT seeks to resolve interpersonal conflicts and mobilize social support. No homework is assigned; instead, IPT encourages self-agency and includes a time limit to press patients to act in interpersonal situations.

An advantage of IPT over cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for military and family populations is its targeted focus on bolstering social engagement and support and addressing feelings of isolation and estrangement to reduce psychopathology (

19,

20). Military veterans and families often lack social support and feel isolated and estranged from civilians who lack military service history (

21). Relocations and deployment cycles compound their social isolation and disrupt community support (

5,

8). Such isolation, disconnection, and absence of social support contribute to adverse general medical and mental health and to the development and persistence of PTSD and depression (

22–

24). IPT and other research suggests that bolstering social support plays an important role in relieving these symptoms (

19,

25).

IPT has established efficacy in treating major depressive disorder (

26,

27), and numerous studies support its efficacy across other disorders and treatment populations (

28). IPT for PTSD performed overall as well as PE in a randomized controlled civilian trial (

29) and better than PE for patients with sexual trauma or comorbid major depressive disorder (

29,

30). (Co-occurrence of PTSD and major depressive disorder is roughly 50% [

31].) Patients also preferred IPT to PE (

13). The VA has disseminated IPT to treat patients with major depressive disorder (

32), and IPT appears in VA/DoD PTSD and depression treatment guidelines (

9); however, the IPT research literature on veterans with either disorder comprises only two non-VA case reports (

33,

34) and two small pilot studies of veterans with PTSD (

35,

36). No previous studies of any individual psychotherapy exist for military family members.

Discussion

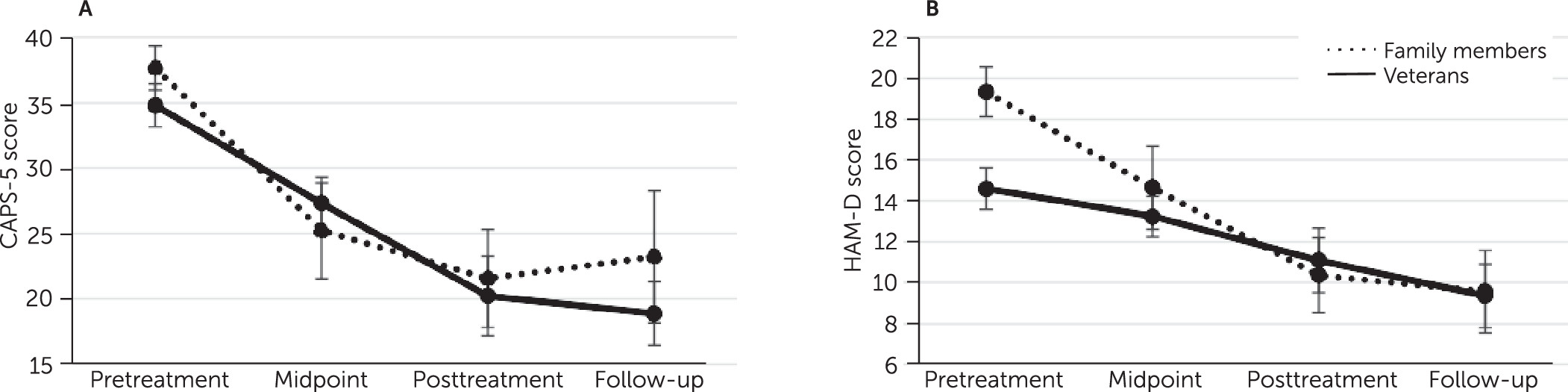

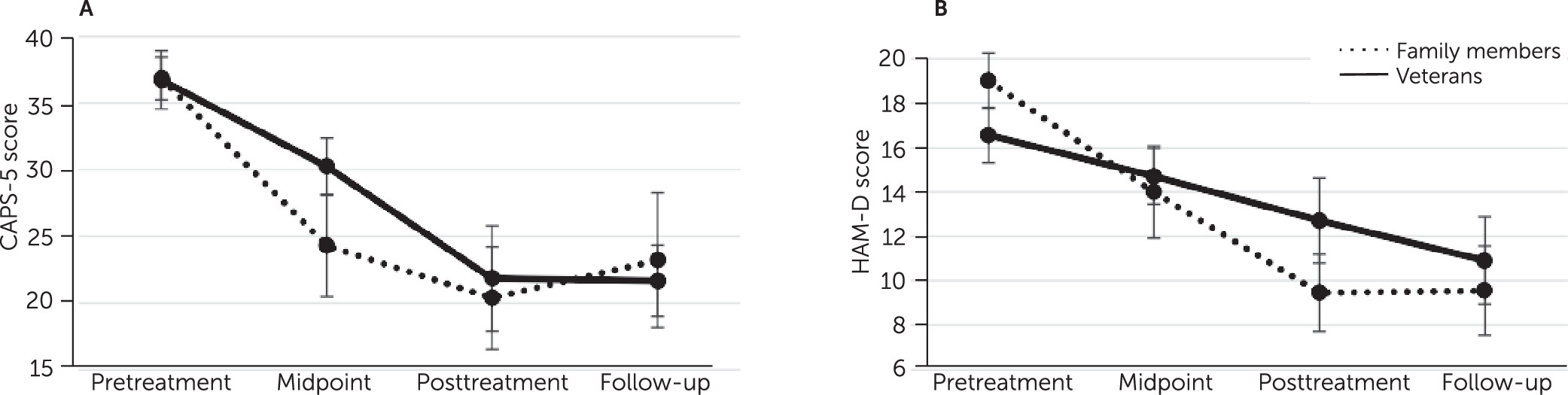

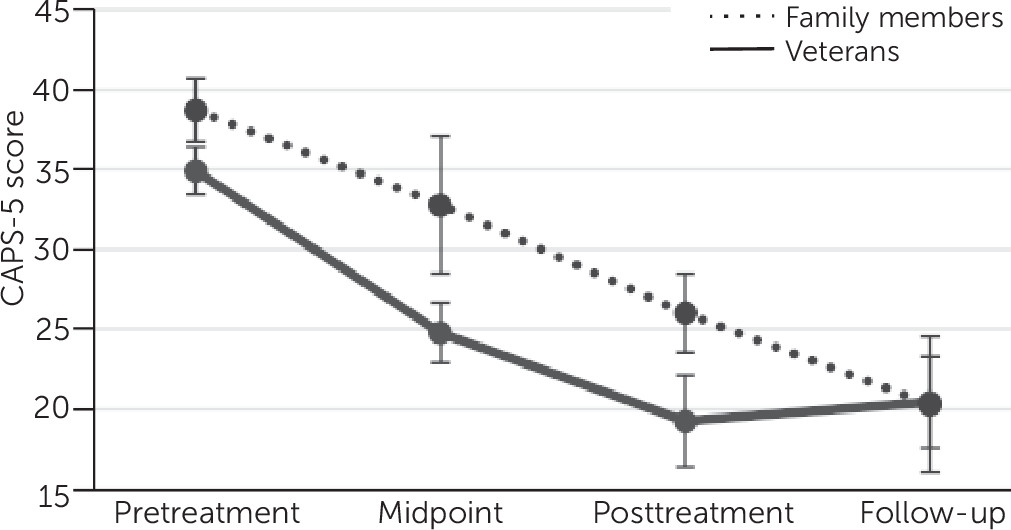

As hypothesized, veterans, service members, and family members receiving IPT in an open trial had improvements in PTSD and depression symptoms over time. These positive results replicate previous findings in a civilian population (

29) and extend them to veterans in the largest study of IPT for PTSD among veterans to date (

35,

36). The findings support the growing recognition that focused systematic exposure to reminders of trauma, while often useful, may not be essential to treat all patients with PTSD (

43,

44).

This open trial is the first study to evaluate IPT—and, to our knowledge, any individual psychotherapy—for military family members. Extant research on military family members is scant and limited to couples or family interventions (

45). This study is the first to directly compare clinical outcomes between veterans/service members and military family members receiving IPT. Previous literature hints that veterans fare less well than civilians in PTSD treatment studies (

18), but we found comparable treatment responses among veterans/service members and quasi-civilian military family members. Attrition was higher for veterans/service members than for family members, consistent with trends reported in the larger PTSD treatment literature (

15).

As previously found (

13), patients with comorbid PTSD and depression who received IPT for PTSD experienced relief of their symptoms. PTSD-depression comorbidity is typically associated with clinical challenges, including treatment dropout and nonresponsivity (

46,

47). Consistent with these complexities, the dropout rate among veterans with comorbid PTSD and depression was 39%, comparable to the 36% rate reported for veterans receiving other forms of PTSD treatment (

15). However, attrition among family members with comorbid PTSD and depression was much lower (7%), lower even than observed among civilian patients with comorbid PTSD and depression in a previous study in which we compared IPT for PTSD (20%), PE (50%), and relaxation therapy (27%) (

29). Because this study treated only 15 family members with PTSD-depression comorbidity, it is premature to draw conclusions regarding treatment tolerability. Among patients who remained in treatment, responses followed a similar improvement pattern, regardless of comorbid condition or veteran/service member versus family member status. The preliminary evidence for IPT’s popularity and durability among veterans, and among patients with diagnostically complex conditions, makes the case for further research on IPT’s utility in the VA system and other settings where veterans seek treatment. IPT’s tolerability among family members further suggests its potential value in broader settings, although the small sample size precludes definitive recommendations.

Although teletherapy was not the focus of the present study, we found that patients who selected teletherapy had somewhat more severe baseline symptoms. These patients also showed declines in PTSD and depression symptoms with treatment. Telehealth for mental health treatment, particularly video conferencing, had gained popularity because it is cost-effective and increases access to high-quality care for rural or incapacitated patients (

48) even before its wholesale adoption in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (

49). Relevant to our sample, to veterans and to individuals with PTSD generally, teletherapy may benefit patients who avoid in-person treatment because of concerns about stigma (

50). Yet, as in this study, telehealth may be a modality that patients with more severe symptomatology prefer, reflecting clinical symptoms of avoidance or behavioral withdrawal (which are often targets of treatment). Tele-IPT research is needed to address its costs and benefits.

Limitations of this open trial included small sample and subsample sizes, attrition, and lack of a control condition, which precludes drawing conclusions about causality. Selective attrition may have yielded inflated estimates of symptom improvement during the treatment. Lack of randomization (all patients had opted for IPT), and the fact that assessors were not blind to treatment or delivery modality, might have biased our findings. Some patients received modifications of their pharmacotherapy regimens, limiting conclusions about treatment outcomes. Some patients received teletherapy, whose equipotency to in-person IPT remains unestablished (

49). Patients receiving tele-IPT appeared to benefit from the treatment, but our teletherapy analyses were likely underpowered. Our military sample findings may not generalize to nonveterans or to patients in VA settings. Future research should use a randomized controlled outcome design to compare IPT with other treatments for military patients. An as yet unpublished multisite randomized VA trial for PTSD and a planned randomized trial for military sexual trauma, both comparing IPT and PE treatments, should provide important comparative data on IPT for PTSD among veterans. Military family members deserve further treatment and research as well. Finally, our data were not well suited to address therapist effects on therapy outcomes; future studies should address these effects. These limitations notwithstanding, there is converging evidence that IPT for PTSD is well tolerated and effective, including for patients presenting diagnostically complex cases.