Suicide ranks 10th among all-cause mortality in the United States, with suicide mortality rates on the rise within recent years (

1). Mental health conditions, including depression, are associated with death by suicide, and severe depression nearly doubles the odds of suicide death (

2). As both weight loss and weight gain constitute part of the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, the potential arises for weight change to be associated with increased risk for suicide (

3). Indeed, the odds of weight or appetite loss among individuals diagnosed as having major depressive disorder who died by suicide was nearly 2.6 times that of controls (i.e., those with depression but without weight or appetite loss) (

4). Other research, however, has not found an association between weight loss and death by suicide during a 5-year follow-up among individuals with depression (

5). Of note, these studies included only individuals with major depression. The need for research examining weight change and suicide mortality rates among larger, more representative samples is supported by data that only 24% of those who died by suicide were diagnosed as having a mental health condition in the month before their death (

6). Therefore, there is a need to identify suicide risk factors beyond psychiatric diagnoses. Nonbiased (e.g., objective) physiological indicators, including weight change, may represent one such risk factor for suicide death.

Only one study to date has examined associations between weight change and suicide among a large sample in London, United Kingdom (

7). In this study of 18,784 men over a 38-year period, 61 reported suicides occurred. Unexplained weight loss over the past year was associated with an elevated suicide risk. However, the study was limited in that unexplained weight loss was self-reported and therefore may have been biased, only men were included in the study, diagnoses of depression were not reported, and the study was conducted outside the United States. Indeed, there is a marked difference in the means used for suicide between individuals in the United Kingdom and the United States, with less lethal means being more commonly used in the United Kingdom (

8). Therefore, the results of the London study (

7) may not be generalizable to both men and women in the United States.

Further evidence for a potential link between weight change and suicide comes from the field of bariatric surgery. Among those who undergo bariatric surgery, which contributes to significant reductions in body weight, rates of suicide death are significantly higher than among those in the general population (

9). Interestingly, however, obesity has been associated with decreased suicide risk in several but not in all studies (

10). Thus, weight loss after bariatric surgery may have an effect that elevates suicide risk. Although existing evidence links specific populations (e.g., individuals with depression or those who have undergone bariatric surgery) with increased risk for suicide death, there is a need to further examine whether weight change is associated with variation in the risk for suicide death among the general population, including individuals with and without depression and other potential suicide risk factors. This study examined these associations while also accounting for the influence of demographic variables, mental or substance use disorder diagnoses such as depression, and medical conditions that may also be associated with the risk for suicide death.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the patient sample are presented in

Table 1. As age and sex were matched, the sample was predominantly male (71%) and 56–57 years old. In general, people who died by suicide were White (69%), had a diagnosis of depression (55%) or another mental or substance use disorder (23%), and a Charlson score >0 (57%), reflective of comorbid condition. Individuals who died by suicide and those in the control group differed significantly by race-ethnicity, mental or substance use disorder diagnosis, and comorbid condition. The two groups did not significantly differ in neighborhood poverty level or neighborhood education. An examination of the change in BMI during the previous year revealed a significant difference between the two groups, with those who died by suicide having lost on average 0.72 kg/m

2, whereas those in the control group gained on average 0.06 kg/m

2 (p<0.001); Cohen’s d effect size for this association was 0.17. None of the individuals who died by suicide received bariatric surgery in the year before their death, and one individual in the control group had received bariatric surgery in the previous year.

An online supplement to this article includes a table comparing the demographic characteristics of individuals in both the suicide death and control groups to those in the entire population from which the study sample was drawn. Our subsample was older and had a higher percentage of female and White individuals, as well as higher levels of medical morbid conditions, mental and substance use disorder diagnoses, and diagnoses of depression than those in the entire sample of individuals who died by suicide. However, the individuals in our sample did not differ from those in the entire sample by neighborhood education level or neighborhood poverty level.

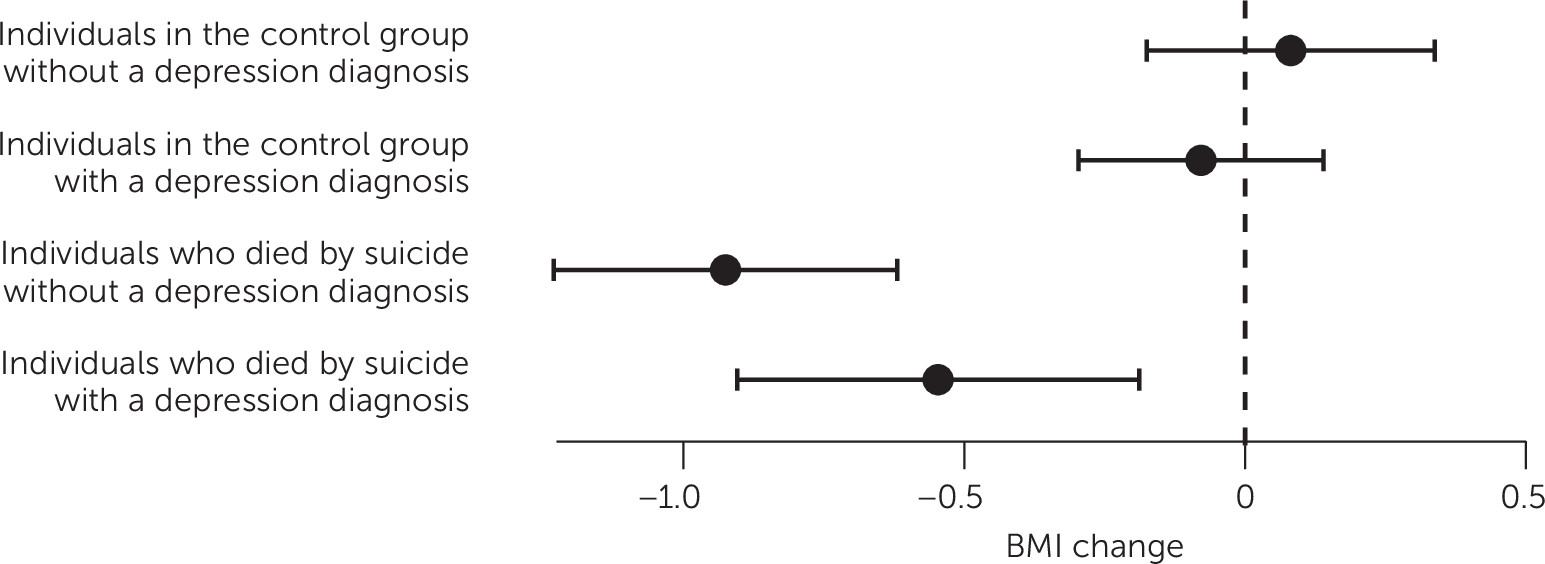

Univariable analyses revealed significant associations between our main outcome, suicide death, and BMI change, race-ethnicity, mental or substance use disorder diagnosis, and comorbid condition (

Table 2). After accounting for demographic predictors, mental or substance use disorder diagnosis other than depression, depression diagnosis, and comorbid conditions, the association between BMI change from the latest to most recent BMI measurement before the index date and suicide death remained statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.11, 95% confidence interval=1.05–1.18, p<0.001), such that a one-unit decrease in BMI was associated with a significantly increased risk for suicide death. The association between BMI change and risk for suicide differed between people with and without a diagnosis of depression. Among those with a depression diagnosis, BMI change and suicide death were not significantly associated with each other (p=0.098). In contrast, among those without depression, we detected a significant association between increased BMI change and decreased suicide risk (p<0.001) (

Figure 1). To assess whether weight loss may have been due to the presence of medical conditions, we tested the interaction between Charlson score and BMI change. We observed a significant association between BMI change and suicide for both those with and without comorbid conditions (

Table 2), suggesting that the association between BMI change and suicide was not restricted to individuals with a comorbid condition.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of death by suicide as documented in medical records from the U.S. general population. After accounting for several demographic, medical, and psychiatric predictors, we found that weight loss in the preceding year is associated with suicide death. Consistent with previous statistics on suicide completion (

1,

14), having a mental or substance use disorder diagnosis or comorbid condition independently increased the odds of suicide death. In the present study, those who died by suicide lost on average about a three-quarter BMI point in the year before their death, which roughly translates to a 4-pound weight loss. However, it should be considered that, from 1992 to 2010, the BMI of U.S. adults who initially had a weight within the normal range increased from 0.7 to 1.1 pounds and, among those who were initially overweight, from 0.4 to 1.3 pounds (

15). In addition, those in the control group gained weight, on average, during the same period. Thus, the observed trend in weight loss among those who died by suicide contrasted both with those in the control group and with population-wide trends of increasing BMI in the United States. Additionally, our finding that individuals who died by suicide on average experienced weight loss in the year before the suicide is consistent with research that BMI and suicide risk are inversely associated. Kaplan and colleagues (

16) noted that each 5 kg/m

2 increase in BMI was associated with an up to 24% lower suicide risk.

The primary findings indicate that suicide death is associated with weight loss in the previous year before the suicide, with a significantly increased risk for suicide death for each one-unit decrease in BMI after adjustments for demographic, psychiatric, and comorbid conditions, although the magnitude of the effect of BMI change on suicide was relatively small. Notably, this association apparently was not accounted for by weight changes attributable to chronic medical conditions, because the BMI decrease was associated with increased risk for suicide regardless of the Charlson score. We note that weight and height are routinely measured at medical visits, making this information highly visible to medical providers (

17). Measured vitals from which a BMI can be calculated provide a value that is not subject to bias associated with personal reporting of weight and height (

18). Suicide screening has been shown to predict future suicide attempts and suicide deaths (

19), illustrating the importance of routine screening, especially among individuals with weight loss.

Despite depression being most strongly associated with suicide death of all the predictors examined, only 55% of individuals who completed suicide were given a diagnosis of depression, and only 23% had a mental or substance use disorder diagnosis other than depression. Interestingly, our results revealed a significant association between weight change and suicide death only among those

without a diagnosis of depression. One possible explanation for this observation is that depression can contribute to weight gain or weight loss, which, when considered together across individuals with depression, could obscure a potential association between suicide death and weight change. Additionally, consistent with previous research, antidepressant medications may attenuate weight change, as they can contribute to both weight loss and gain (

20). However, the nonsignificant interaction between weight change and depression diagnosis should not be interpreted to mean that weight change is not pertinent among those with depression. Rather, it is possible that weight loss may confer a risk for depression.

The evidence presented here suggests an association between weight loss and suicide death, although causality could not be ascertained. One possibility is that the relationship is direct, with weight loss increasing the risk for suicide. For example, hormones, including ghrelin, may be responsible for the association between weight loss and suicide, as has been posited for those who have undergone bariatric surgery (

9). Alternatively, it is possible that weight loss is a marker for the “true” cause of suicide. As such, weight change may be an “externalized” indicator of depressive symptoms or other mental health symptoms. Research has also found lower levels of triglycerides among those who attempted suicide (

21), and triglyceride levels are shown to decrease with modest weight loss in overweight and obese individuals (

22).

The strengths of this study include the large sample of individuals who died by suicide and vital measurements derived from reliable medical record data from health systems across the United States. Our results may inform clinical care by shedding light on the relevance of weight loss as a potential psychiatric marker for suicide. Additionally, the findings may be used to guide future studies that use predictive modeling of risk for suicide.

We note several limitations. People who died by suicide and people in the control group were included if they had at least two weight measurements in the year before the index date. However, the ability to determine the elapsed time between the measured weights could vary significantly across patients. Indeed, we found greater variability in BMI change as the number of elapsed days between weight measurements increased, which is to be expected. Therefore, future efforts to expand this study would benefit from a prospective study design to capture weight measurements at clinically relevant, potentially vulnerable time points for suicide across the life span, such as within 3 months of an emergency department visit or inpatient stay due to a mental health condition (

23). Because we included only individuals with two or more health care visits in the previous year, it is important to also consider that these individuals may have been more engaged in their health care, which may have biased the findings. Indeed, the patients in our sample had higher levels of medical and psychological comorbid conditions.

Additionally, this study did not examine suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, which are associated with suicide death (

2) as well as with weight control behaviors (

24) and perceived weight status (

25). Examining associations among objective weight change, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts would be a valuable future research direction. Additionally, assessing whether weight loss was either intentional or unintentional could have implications for suicide risk and subsequent treatment, as demographic risk factors such as older age, poorer health status, and lower BMI are associated with both suicide and unintentional weight loss (

26). Last, this study did not include use of antidepressant medication, which could have contributed to weight changes, and did not consider medical conditions that could contribute to edema, which has a small positive correlation with weight (

27). Future studies should consider the potential influence of specific medical conditions and of antidepressant use, including medication type, dosage, and adherence, on the relationship between weight changes and suicide risk.