Difficulty accessing affordable treatment is a leading reason for undertreatment of substance use disorders (

4). Lack of health coverage can pose financial barriers to treatment, especially for adults with low income (

5), who have elevated risks of substance use disorders (

6). To help meet the health care needs of low-income adults, the Medicaid expansion provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) was implemented in January 2014. Although expansion increased Medicaid coverage to approximately 13.1 million low-income Americans (

7), several states opted out of this provision. This decision may have had important implications for access to substance use treatment (

8).

Buprenorphine treatment can effectively manage opioid withdrawal and prevent relapse, and buprenorphine is the most widely prescribed medication for opioid use disorder (

9–

13). After expansion, Medicaid-financed buprenorphine prescriptions increased faster in expansion than in nonexpansion states (

14,

15). However, it is unknown whether these gains translated into population-wide differences in buprenorphine treatment across expansion and nonexpansion states or whether the policy resulted in improved treatment retention and dosing of buprenorphine. In this study, we provide the first population-wide assessment of the effects of Medicaid expansion on buprenorphine treatment patterns and on the quality of buprenorphine treatment among patients receiving Medicaid.

Recent ecological research (

16–

18), which has received extensive attention in the media (

19,

20), has linked Medicaid expansion to slower growth in opioid overdose (

16), drug overdose (

17), and substance use disorder–related deaths in expansion states (

18). It has been hypothesized that Medicaid expansion reduced overdose deaths by differentially increasing buprenorphine treatment in expansion states (

16,

18). In support of this hypothesis, opioid overdose accounts for most drug overdose deaths (

21), buprenorphine is the most widely prescribed medication for opioid use disorder (

9), and consistent buprenorphine treatment lowers the risk for death among patients with opioid use disorder (

22). Yet, most adults with opioid use disorder have private insurance (

23), and the effects of Medicaid expansion on buprenorphine treatment at a national population level have not been previously examined.

To evaluate whether Medicaid expansion had population-wide effects on buprenorphine treatment consistent with greater declines in opioid-related deaths in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states, we characterized national changes in buprenorphine treatment after Medicaid expansion. We hypothesized that Medicaid expansion would drive greater population-wide increases in buprenorphine-treated patients in expansion states than in nonexpansion states. We also explored whether expansion spurred changes in the fraction of Medicaid-financed patients reaching benchmarks in buprenorphine treatment retention and dosing quality.

Results

Trends Among All Patients Treated With Buprenorphine

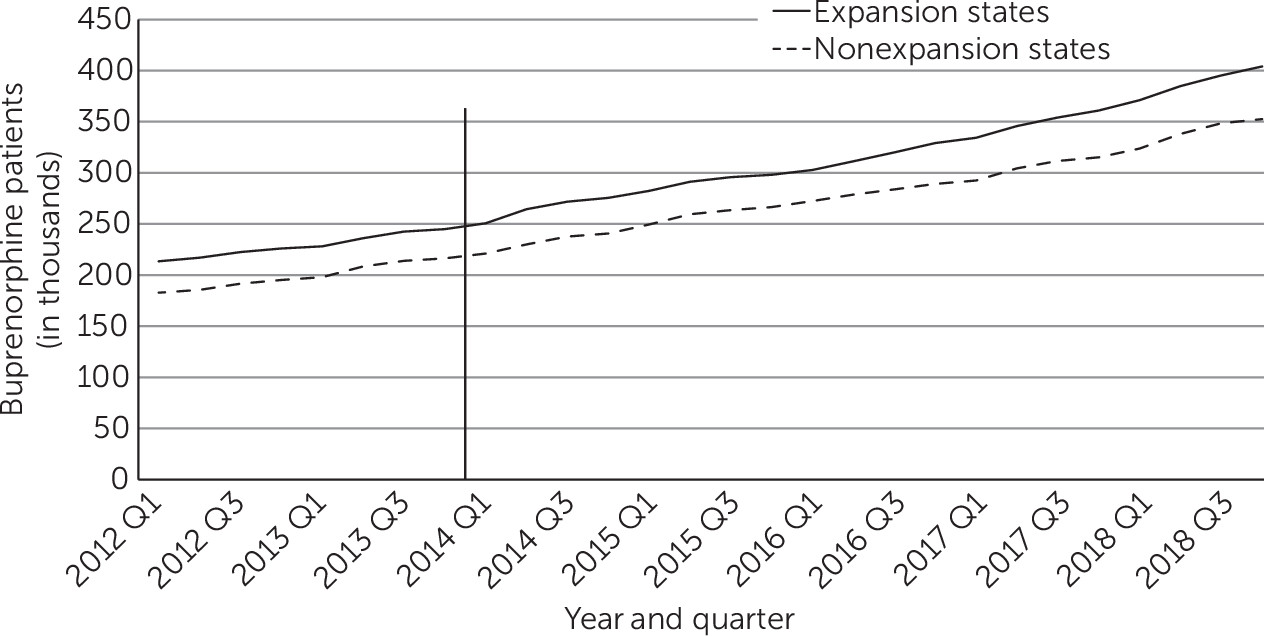

Over the 2012–2018 period, roughly parallel increases occurred in the mean quarterly number of all patients treated with buprenorphine in expansion and nonexpansion states (

Figure 1). Between the pre- and postexpansion periods, in each yearly quarter the number of patients treated with buprenorphine increased by 93,300 (95% confidence interval [CI]=59,570 to 127,020) in expansion states and by 84,960 (95% CI=55,590 to 114,320) in nonexpansion states (

Table 1), a difference that was not statistically significant. In both expansion and nonexpansion states, the increases were largest among patients ages 25–44, and buprenorphine prescriptions significantly declined among people ages 16–24.

In expansion states, the mean quarterly number of treated patients covered by Medicaid increased by 28,760 (95% CI=15,660 to 41,870), whereas the corresponding increase in nonexpansion states was more modest (4,050 patients, 95% CI=1,250 to 6,840). As a result of the disproportionate increase in Medicaid-financed buprenorphine treatment in expansion states, the percentage of total Medicaid-paid buprenorphine prescriptions in expansion states nearly doubled from 9.87% (95% CI=9.80 to 9.94) to 18.91% (95% CI=18.85 to 18.97) during the study period, whereas the corresponding increase in nonexpansion states was smaller, from 7.53% (95% CI=7.47 to 7.59) to 7.90% (95% CI=7.86 to 7.95) (see online supplement).

Buprenorphine Treatment per 100 Persons With Nonmedical Opioid Use

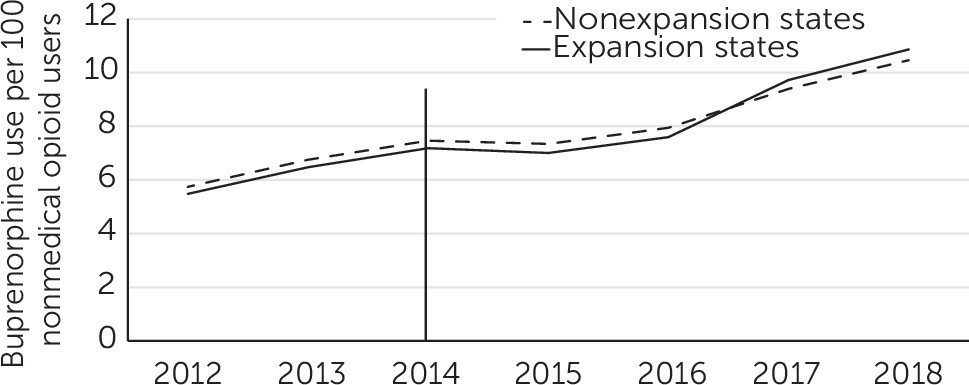

During the study period, the rates of buprenorphine treatment per 100 persons with past-year nonmedical prescription opioid use were similar in expansion and nonexpansion states (

Figure 2). Between 2012 and 2018, these rates increased from 5.5 to 10.9 per 100 persons in expansion states and from 5.7 to 10.5 in nonexpansion states.

Trends Among Medicaid-Financed Patients Treated With Buprenorphine

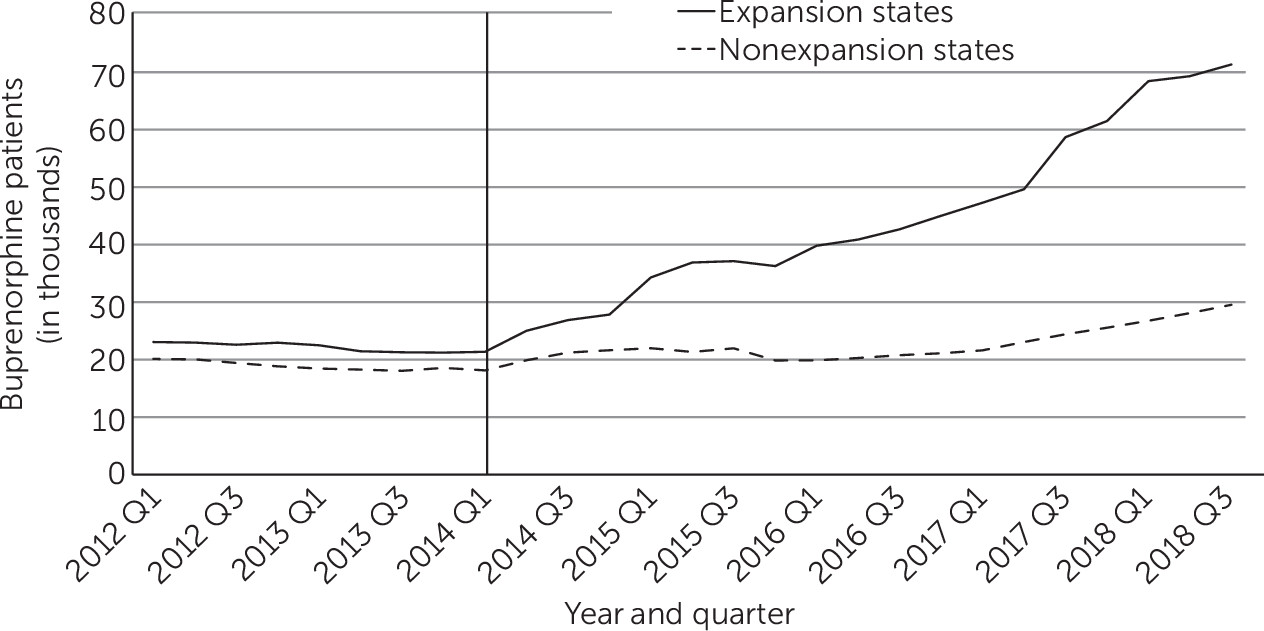

During the preexpansion period, the numbers of and changes in Medicaid patients treated with buprenorphine in each yearly quarter were similar in expansion and nonexpansion states. After the policy intervention, however, the rise in buprenorphine treatment was greater in expansion than in nonexpansion states (

Figure 3). During the postexpansion period, an estimated 59,830 Medicaid patients per quarter were treated with buprenorphine in expansion states who would not have been treated had the policy not been enacted. The corresponding number in nonexpansion states was 16,730 (see

online supplement). The largest gains occurred among adults ages 25–34 in expansion states, followed by those ages 35–44 (see

online supplement).

After excluding from the analysis states that expanded Medicaid before 2014 or in 2015 through 2018, an estimated 43,850 (95% CI=17,990 to 69,220) additional Medicaid patients at the end of the expansion period received buprenorphine in expansion states, whereas the estimated policy-related increase was not statistically significant in nonexpansion states (9,260 patients, 95% CI=−1,030 to 19,560).

Among new episodes of buprenorphine treatment of Medicaid patients, no significant change occurred in the proportion reaching the 180-day duration threshold in expansion states (increase of 21.9% to 24.6%, difference=2.7 percentage points, 95% CI=−7.4 to 12.7) and nonexpansion states (23.1% to 28.0%, difference=4.9 percentage points, 95% CI=−5.6 to 15.5). A significant decline in the proportion that included prescriptions for ≥16 mg/day was detected in expansion states (from 68.2% to 62.7%, difference=−5.5 percentage points, 95% CI=−9.3 to 1.7) and a nearly statistically significant decline was observed in nonexpansion states (from 73.4% to 70.5%, difference=−2.9 percentage points, 95% CI=−5.9 to 0.0).

Trends Among Non–Medicaid-Financed Patients Treated With Buprenorphine

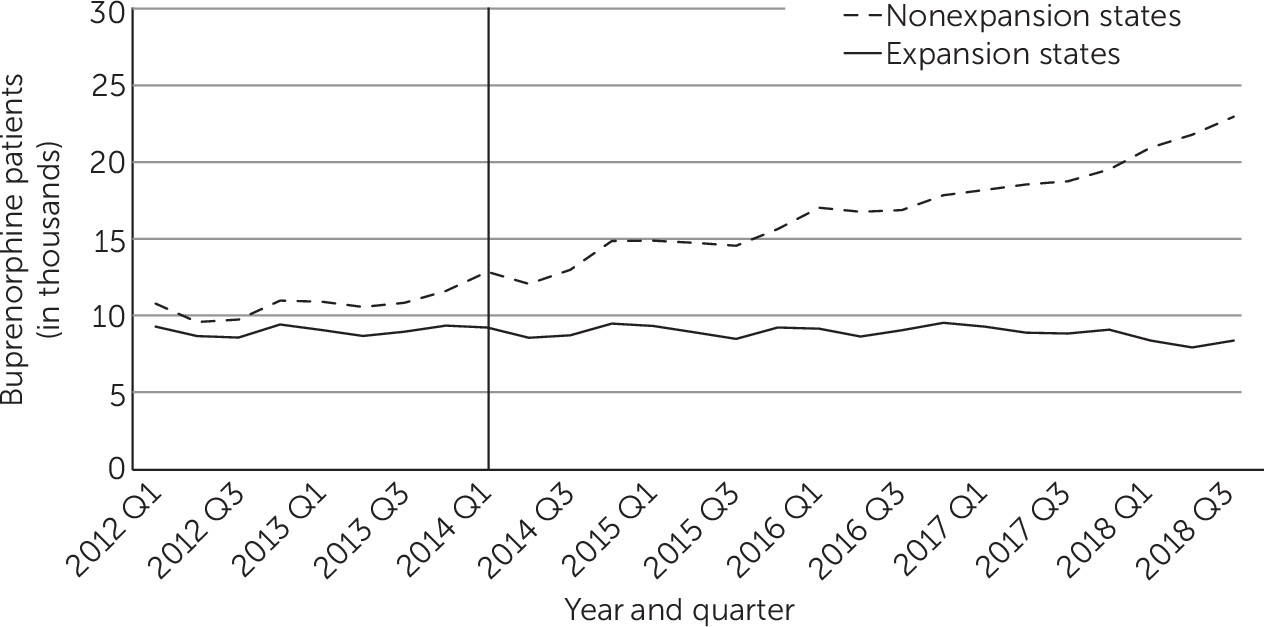

During this period, the mean quarterly number of self-pay patients who were treated with buprenorphine increased from 10,610 to 17,290 in nonexpansion states and declined slightly from 8,980 to 8,890 in expansion states (

Table 1 and

Figure 4). Trends among buprenorphine-treated patients who were financed through private insurance and other public insurance were similar in expansion and nonexpansion states (see

online supplement).

Discussion

Medicaid expansion coincided with a disproportionate increase in the number of Medicaid-financed patients receiving buprenorphine in expansion states. This increase did not, however, translate into a significantly greater population-wide increase in buprenorphine treatment in expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states. Because of offsetting increases among buprenorphine-treated patients who were uninsured or who had other payment sources in nonexpansion states, we observed nearly parallel increases in the total number of buprenorphine-treated patients in expansion and nonexpansion states. Similar trends were observed in buprenorphine treatment rates of people who misused prescription opioids. Despite these increases, the national volume of buprenorphine treatment remained remarkably low, estimated at approximately 300,000 per yearly quarter, far below a conservative (

30) estimate of approximately two million U.S. individuals with opioid use disorder (

31).

Although Medicaid is a vital source of health care coverage for people with low income and disabilities, it accounts for only a modest proportion of overall buprenorphine treatment coverage in the United States. During the years immediately before expansion, Medicaid covered 12% of buprenorphine treatment episodes in expansion and nonexpansion states. Given its modest coverage contribution to the total national buprenorphine supply, it is not surprising that the increase in Medicaid-covered buprenorphine treatment in expansion states did not drive a significant overall increase in buprenorphine treatment in these states. The increase in Medicaid-financed treatment in expansion states was offset by increases in self-pay in nonexpansion states. Left without insurance, those in need of treatment in nonexpansion states may have opted to pay out of pocket. This pattern suggests that one important function of Medicaid coverage was to reduce financial burden arising from out-of-pocket costs.

Private insurance was the dominant buprenorphine payment source during the study period, accounting for more than three-quarters of patients who were treated with buprenorphine. This percentage exceeds the estimated 53% of people with opioid use disorder who have private insurance (

23). Our findings suggest that privately insured individuals with treatment needs were disproportionately treated with buprenorphine. This finding is consistent with previous work indicating that buprenorphine tends to be provided in more affluent and less racially diverse communities (

32,

33) and that substance use clinics that offer medications for opioid use disorder tend to accept private insurance (

34).

The treatment trends we report here have implications for recent ecological research reporting that Medicaid expansion has slowed substance use–related mortality (

16–

18). These findings have led to the hypothesis that mortality reductions in expansion states are due to increased buprenorphine treatment (

16,

18). However, population-wide buprenorphine treatment trends cast doubt on whether Medicaid-financed gains in buprenorphine treatment have slowed overall drug-related mortality rates more in expansion states than in nonexpansion states. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that greater buprenorphine-related reductions in mortality rates in expansion states were associated with the outsized impact on Medicaid patients, who may have higher illness severity (

35) and mortality risk than other patients who are treated with buprenorphine. It is also possible that other factors may have accounted for these reductions in mortality rates, such as Medicaid-related improvement in financial security (

36), Medicaid-financed naloxone-based overdose reversal (

37), methadone or naltrexone treatment, and other Medicaid-financed mental health or substance services (

14).

Our findings extend previous research on the volume of buprenorphine prescribing after Medicaid expansion (

14,

15) by including national trends in the number of patients prescribed buprenorphine. Consistent with the previous research, we noted that Medicaid expansion was associated with an increase in Medicaid-financed buprenorphine treatment that was greater in expansion than in nonexpansion states. Some previous studies, including a natural coverage experiment, the Oregon Medicaid lottery (

38), and a time-series study based on population (

39), did not find a significant increase in opioid use disorder treatment after Medicaid coverage. However, these studies were likely underpowered to evaluate this outcome.

Our results contrast with a five-state study of 2011–2016 IQVIA LRx data that reported an increase in the overall rate of nonelderly adults treated with buprenorphine in counties of expansion states, compared with nonexpansion states (

40). In that analysis, significant corresponding changes were not found in Medicaid-financed buprenorphine prescriptions or number of medication days. Differences in study populations, study periods, units of analysis, and analytical methods may help to explain these contrasting results.

Several factors may have contributed to overall rising rates of buprenorphine treatment in expansion and nonexpansion states during the study period. First, the burden of opioid use disorder increased during this period. Second, practice guidelines and clinical research published during that time supported buprenorphine’s effectiveness for managing opioid use disorder. Third, federal policies increased buprenorphine prescriber waiver limits and broadened the range of health care specialists eligible to receive waivers. Finally, several other contemporaneous health care reforms may have played a role. These reforms included Marketplace exchanges that enrolled >10 million people in private health insurance each year from 2016 to 2018 (

41), most of which provided at least some coverage of buprenorphine; the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2016, which increased buprenorphine patient limits for individual prescribers from 100 to 275; and the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, which extended buprenorphine waiver options to physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

Adults ages 25–44, have borne a particularly heavy burden of the opioid epidemic, with high and rapidly increasing rates of opioid-involved overdose deaths (

42). It was therefore encouraging that the fastest growth of Medicaid-financed buprenorphine treatment occurred in this age group. It was also encouraging that the rate of buprenorphine treatment of those who misused prescription opioids increased during the study period.

Problems with retaining patients on buprenorphine (

43) and achieving adequate dosing undermine the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment in community practice (

44). In addition to increasing treatment access through Medicaid expansion, the ACA offered hope of improving the quality of substance use treatment by integrating and coordinating the care of dually eligible Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries with substance use disorders via Medicaid health homes and coordinated care organizations (

45). The present analysis, however, provides no evidence of improvements over time in the proportion of Medicaid-covered, buprenorphine-treated patients reaching dosing and duration thresholds. Instead, we observed a nonsignificant trend toward a declining proportion of new episodes reaching the dosing threshold, which raises concerns about a decrease in quality of buprenorphine treatment during a period of rapid growth in buprenorphine prescribing that may be related to less-experienced buprenorphine prescribers (

46) or to changes in patient case mix.

This analysis had some limitations. First, the accuracy of population IQVIA coverage estimates was uncertain. Second, the prescription data represented buprenorphine purchases rather than consumption, and assessment of illicit diversion was not possible (

47). Third, we could not exclude patients treated with off-label buprenorphine prescribing for chronic pain. This group accounts for approximately 11% of buprenorphine prescriptions (

48). Finally, the NSDUH survey item concerning nonmedical prescription opioid use is a crude and broad proxy to index trends in treatment need.