Youth suicide has increased in recent years, and preventing youth suicide is a global health priority (

1–

3). Available evidence indicates that sexual and gender minority youths (SGMY) are more likely to consider, attempt, and die by suicide, compared with heterosexual and cisgender youths (

4–

9). Because of a paucity of longitudinal research, little is known about why some SGMY who think about suicide make an attempt, whereas most do not (

10,

11). Despite the persistence of these disparities, there are no well-established interventions tailored for this population (

12,

13). Prospective research is urgently needed to develop strategies to predict and prevent suicide attempts among SGMY (

14,

15).

Several recent advances inform future directions in establishing an evidence base for addressing suicidality among SGMY. First, developing methods for screening—the proactive identification of youths experiencing suicidality—is crucial (

16,

17). Correlates of suicidal behavior are more prevalent among SGMY, which may lead to different overall risk profiles (

18–

21). Novel, electronically delivered health interventions to address SGM health disparities have good efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability (

22,

23). Evaluating available screening tools, particularly those that can be delivered electronically, in this population will inform efforts to identify SGMY at high suicide risk and facilitate linkage to intervention.

Second, ascertaining factors that predict transitions from suicidal thoughts to behaviors can clarify targets for intervention (

24,

25). Predicting suicide attempts among youths is challenging, and this is especially the case for SGMY (

4,

26). However, research on youth suicide risk screening indicates that presence of a combination of symptoms of mood disorders and alcohol and drug use disorders effectively identifies youths at risk and may be informative in predicting SGMY risk (

17). Additionally, the ability to identify within-person factors associated with transitions in risk can inform our understanding of the naturalistic course of suicidality, effectiveness of screening strategies, and individualization of interventions (

27,

28). To date, only three published studies have examined suicidality longitudinally among SGMY (

29–

31). Nevertheless, these studies consistently found that attempt history and suicidal ideation severity were better predictors than previously examined SGM-specific factors (e.g., child gender nonconformity). Thus, characterizing suicidality specifically is likely to aid in predicting risk transitions. Additionally, interpersonal factors, such as SGM-related victimization and perceived social support, have been found to be associated with retrospective reports of suicide attempt history and prospectively with changes in suicidal thoughts (

29,

32). As such, their role in suicide risk transitions should be explored further.

Third, computerized adaptive testing (CAT) provides advantages over standard approaches to mental health assessments (

33,

34). For instance, structured interviews have good predictive validity but are subject to clinical judgment and require administration by trained interviewers (

35). Self-report measures can be administered in a wide range of settings but have modest predictive validity (

36–

38). Both methods often require the administration of a large number of items from static item banks and screening batteries. In contrast, CAT allows the number and sequencing of items to vary as a function of participants’ previous responses, facilitating personalized assessment with a high degree of accuracy for a range of mental health conditions, including major depressive disorder (

39,

40). The recently developed Computerized Adaptive Test for Suicide Scale (CAT-SS) has demonstrated convergent validity with structured clinical interviews and may improve risk formulation (

41).

The aim of this study was twofold. First, we sought to identify risk and protective factors for transitions from suicidal thoughts to behavior among SGMY. Second, we examined the predictive validity of CAT-SS when the analysis controlled for other risk and protective factors.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from two ongoing accelerated cohort studies of SGMY residing in Chicago, with youths assigned male at birth (RADAR project; current enrollment, N=1,153) and female at birth (FAB400 study; current enrollment N=488). The eligibility criteria and recruitment procedures of these studies have been described previously (

42,

43). Informed consent was obtained from all participants at enrollment. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at Northwestern University and University of Chicago.

Of the 1,641 participants enrolled in these studies, 1,072 completed CAT measures at one visit between January 2018 and July 2018 (subsequently referred to as baseline). Most of the 1,072 participants completed at least one follow-up visit (N=1,006, 94%). The number of follow-up visits after CAT administration varied across participants (median of three visits, range 1–4 visits). Participants without follow-up data did not differ from the analytic sample in age, race-ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were measured at all follow-up visits conducted over 16.5±3.7 months (range 6–24 months). The mean±SD age of the 1,006 participants was 20.7±3.2 years, with most identifying as cisgender (N=841, 84%) and with a nonmonosexual sexual orientation (N=522, 52%). The racial-ethnic distribution was as follows: Black (N=354, 35%), Latinx (N=294, 29%), White (N=237, 24%), and other (N=121, 12%).

Measures

Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Participants completed items from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey to assess suicidality. Suicidal ideation was assessed with the question, “During the past 6 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” Attempts were assessed with the question, “During the past 6 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” Response options were measured on an ordinal frequency scale: zero times, one time, two or three times, four or five times, and six or more times. These items have good convergent and discriminant validity and test-retest reliability (

44,

45).

CAT-SS.

Participants completed the CAT-SS as a measure of recent suicide risk at one visit. The CAT-SS was developed by using methods of multidimensional item response theory in a sample of psychiatric patients and then validated in a sample of emergency department patients. The item bank of 111 items was developed from an initial pool of 1,008 items assessing the domains of anxiety, depression, and mania (including 11 items directly assessing suicidal ideation). With an item bank that assesses multiple domains, participants completing the CAT-SS receive prompts that vary in how directly the items inquire about suicide-related distress. Examples of suicidality-specific items include, “My life lacked meaning and purpose,” and “Did you think about taking your own life?” With a mean of 10 adaptively administered items, the CAT-SS can accurately measure suicide risk in approximately 2 minutes. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe suicide risk. The CAT-SS has demonstrated convergent validity with clinician-administered assessment of suicidality, the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (

41,

46).

Computerized Adaptive Diagnostic Test for Major Depressive Disorder (CAD-MDD).

The CAD-MDD is a computerized adaptive test used to screen for the presence of major depressive disorder (

39). Respondents are presented with questions drawn from a bank of 88 items that map onto domains assessed in the diagnosis of major depressive disorder: negative affect, anhedonia, sleep disturbance, weight fluctuation, psychomotor changes, fatigue, negative self-perception, concentration impairment, and suicidality. The sensitivity and specificity of the CAD-MDD to detect major depressive disorder (based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5) are 0.95 and 0.87, respectively.

Computerized Adaptive Test–Depression Inventory (CAT-DI).

The CAT-DI provides an assessment of depression symptom severity on a scale of 0–100 (

40). Items are drawn from a bank of 389 items assessing domains of major depressive disorder. In previous studies, the CAT-DI has had convergent validity with clinician-administered structured diagnostic interviews, with a sensitivity of 0.92 and specificity of 0.88, and convergent validity with the clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale of r=0.75.

Depressive symptoms.

Depression was measured with the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression–Short Form 8A (

47). This scale measures depressive symptoms in the past week (e.g., negative affect and worthlessness). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1, never, to 5, always). Measure reliability is high in both cohorts (RADAR, α=0.95; FAB 400, α=0.94) (

48).

Alcohol use.

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 10-item tool that assesses alcohol consumption and related impairment (

49). The AUDIT yields a summary score (ranging from 0 to 40), with higher scores indicating greater consumption and functional impairment. Consistent with previous studies of suicide risk in this age group, scores of ≥8 were classified as high-risk alcohol use (

50,

51). This measure has high reliability in these cohorts (RADAR, α=0.81; FAB 400, α=0.81) (

48).

SGM-based victimization.

A 10-item measure was used to assess SGM-related victimization (

52). Participants are asked to report on a 4-point scale (ranging from 0, never, to 3, three or more times) how often they experienced verbal and physical threats and assaults in the past 6 months because they “are, or were thought to be, gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender.” Measurement reliability is high in these cohorts (RADAR, α=0.86; FAB 400, α=0.87) (

48).

Social support.

Participants completed the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (

53). The measure assesses the extent to which participants receive support from family, friends, and significant others. Respondents rate agreement with items (e.g., “My family really tries to help me”) on a 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 1, very strongly disagree, to 7, very strongly agree). The total support subscale was used in this study and has high reliability (RADAR, α=0.88; FAB 400, α=0.90) (

48).

Statistical Analysis

Primary analyses examined the extent to which baseline characteristics and baseline CAT-SS scores predicted suicide attempts in the overall sample and transitions from suicidal ideation to subsequent attempt. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine time to suicide attempt at follow-up in the overall sample and in models stratified by baseline history of suicidal ideation. Associations between baseline factors and suicide attempts were examined in bivariate models (i.e., single predictor) and multivariate models (i.e., all predictors). A positive screen for depression on the CAD-MDD was included as a dichotomous variable (positive or negative screen). CAT-SS scores were divided by 10 to increase interpretability in terms of a unit change on a 10-point scale and analyzed as a continuous measure.

We also conducted post hoc exploratory analyses to assess whether CAT-SS scores could be used to stratify participants into low- and high-risk groups. To test this, we used a log-rank test to determine whether a score ≥5 (≥50 on the original 100-point scale) distinguished participants with a higher risk for an attempt. For participants who reported multiple attempts, data were censored after the first attempt. Gender minority status, nonmonosexual sexual orientation, and race-ethnicity were examined as potential covariates but did not alter study findings. In sensitivity analyses, alternative models were examined, with depressive symptoms measured with the CAT-DI and the PROMIS-8 (see tables in an

online supplement to this article). Analyses were conducted with Stata, version 16.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The characteristics of the overall sample and of suicide ideators and nonideators at the time of CAT-SS administration are presented in

Table 1. At baseline, 258 participants (26%) reported a history of suicidal ideation, and 73 participants (7%) reported a history of suicide attempt. Suicide ideators were more likely than nonideators to report being assigned female at birth, gender minority status, and nonmonosexual sexual orientation and were less likely to report racial-ethnic minority status. Compared with nonideators, ideators reported more frequent victimization, more severe depressive symptoms, and less social support and had higher CAT-SS scores.

Longitudinal Analysis

At follow-up, 32 of the 1,006 participants reported at least one suicide attempt, with half of attempts occurring in the 6 months after the CAT-SS administration at baseline. Bivariate associations between study variables and prospectively observed suicide attempts are detailed in

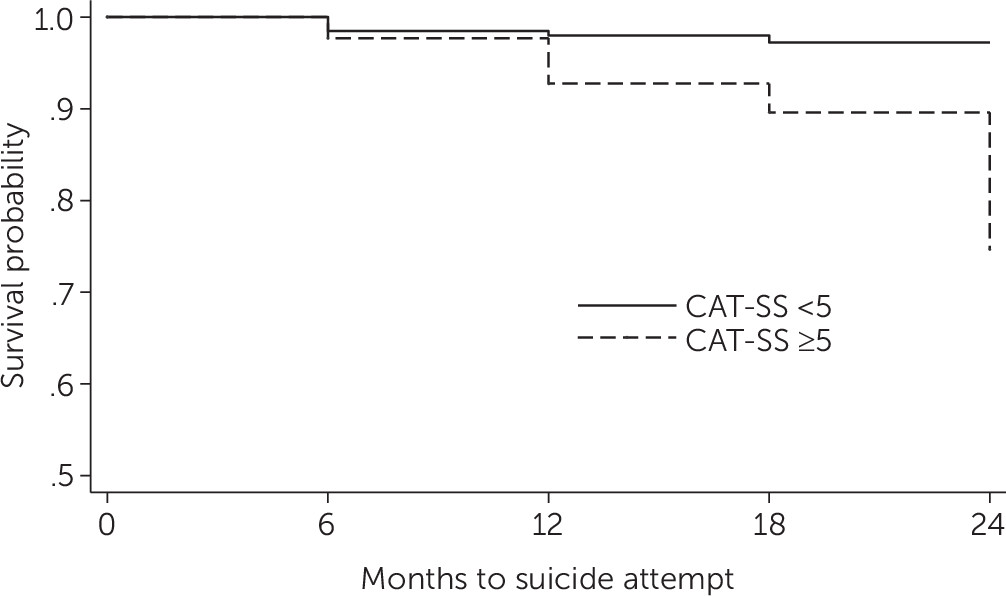

Table 2. In the overall sample, all variables except alcohol use predicted suicide attempts. Among nonideators, social support attenuated the risk for a suicide attempt. Among ideators, victimization increased the risk for suicide attempt. A CAT-SS score of ≥5 was statistically significantly associated with time to suicide attempt (log-rank test χ

2=14.94, df=1, p<0.001;

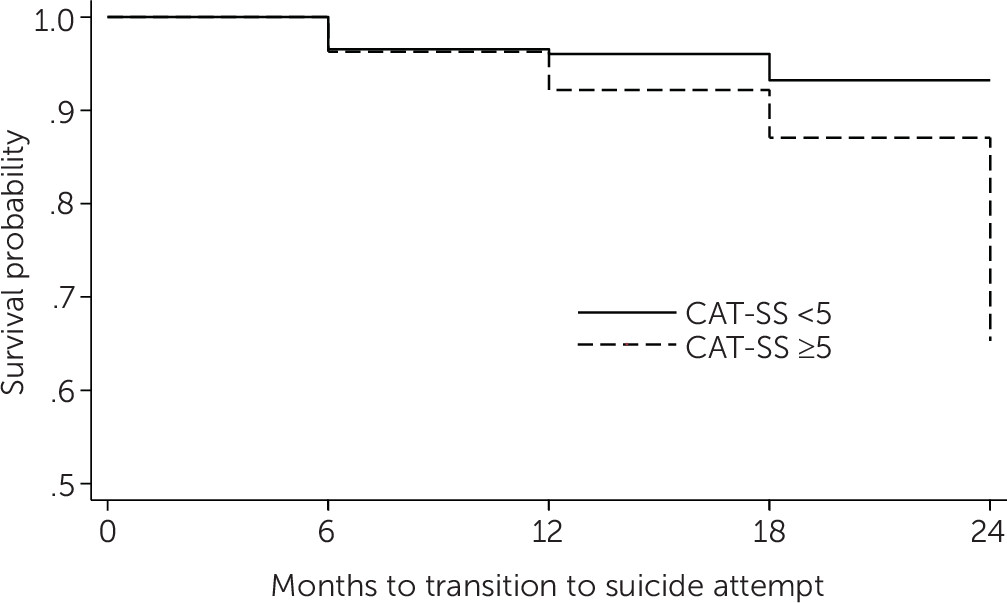

Figure 1). This relationship was attenuated in predicting the transition from suicidal ideation to attempt (log-rank test χ

2=2.86, df=1, p=0.09;

Figure 2).

In multivariate analyses, key predictors within the overall sample included CAT-SS score and victimization (

Table 3). Among nonideators, social support was a protective factor for suicide attempts. For suicide ideators, CAT-SS score and victimization predicted transition to suicide attempt. The CAT-SS predicted suicide attempts in the overall sample (hazard ratio [HR]=1.34, p<0.05; see

Table 3). For the CAT-SS, this represents a 34% increase in risk for a suicide attempt for each 10-point change. Among ideators, the CAT-SS also predicted suicide attempts (HR=1.51, p<0.05), representing a 51% increase in risk for transition from suicidal ideation to attempt for a 10-point change in score—or up to a fivefold increase in transition risk across the range of the scale. A positive screen for major depressive disorder on the CAD-MDD item was not associated with suicide attempts in the overall sample or among nonideators, and a modest but nonsignificant association was observed for ideators (HR=0.29, p=0.08). In sensitivity analyses, we examined multivariate models with alternative measures of depressive symptoms. The CAT-DI and PROMIS-8 were not significantly associated with suicide attempts (see tables in

online supplement).

Discussion

This study examined the predictive validity of the CAT-SS for future suicide attempts, for the transition from suicidal ideation to attempts in a large sample of SGMY, and in combination with adaptive and static measures of depressive symptoms. Variables evaluated included self-report measures of risk and protective factors, as well as a computer-adaptive measure of suicidality, the CAT-SS. This adaptive approach allowed for administered items to vary in the content, number, and order of presentation, potentially providing more tailored and dynamic assessments of suicide risk. Three key findings emerged. First, predictors of suicide attempts differed between youths with and without a history of suicidal ideation at baseline. Social support was associated with reduced risk among nonideators, whereas victimization predicted transition to attempts among ideators. Second, the CAT-SS had predictive validity as an individual predictor, as well as in combination with other factors, of suicide attempts and risk transitions in multivariate models. Third, the CAT-SS predicted suicide attempts regardless of the type of measure of depressive symptoms. Thus, the CAT-SS reliably predicted suicide attempts when examined alone or in combination with other risk and protective factors.

Several strengths of this study represent important contributions to the literature. This study included a large sample and a prospective design. To date, only three studies have examined longitudinal predictors of attempts among SGMY. Stratifying by suicidal ideation history revealed factors associated with both increased and reduced risk for attempts. As found in previous studies, heavy alcohol use did not predict suicide attempts. Similarly, the predictive effects of depressive symptoms were reduced after accounting for other risk and protective factors. In ancillary analyses, the CAD-MDD was associated with a somewhat higher (but nonsignificant) likelihood of suicide attempt in the overall sample when examined alone but a lower (also nonsignificant) likelihood of transitioning from suicidal ideation to attempt in multivariate models. This finding may reflect risk profile differences between youths with and without a history of suicidal ideation. A positive CAD-MDD screen in the overall sample may have indicated risk for any suicidality. Among youths with suicidal ideation, a positive CAD-MDD screen may reflect particular impairments that can reduce the likelihood of engaging in suicidal behavior (e.g., fatigue, sluggishness, and hypersomnia).

Moreover, the predictive validity of the CAT-SS is encouraging. The CAT-SS appeared to predict future suicide attempts—and beyond what is explained by having a history of suicidal ideation. Additionally, the adaptive means of administration and large item bank allowed for indirect assessment of suicidality. This aspect is a notable advantage, because a direct assessment could underestimate risk for individuals who may have risk that fluctuates over time and for individuals who tend to underreport suicidal thoughts. CAT-SS assessments appear to improve the accuracy of prediction of future suicide attempts, which opens the door to large-scale suicide prevention. Online health interventions for SGMY are feasible and efficacious (

22,

23). As such, the availability of computerized evidence-based assessment of suicidality can aid in reaching larger numbers of SGMY.

This study’s findings should be interpreted with its limitations in mind. First, the sample was drawn from two cohort studies based in Chicago. Future research should examine the extent to which these findings can be replicated in more broadly representative samples. Second, the incidence of suicide attempts in this sample during the follow-up period may have limited statistical power to detect small effects. Because the HRs had relatively modest sizes (i.e., <2), it is important to treat these findings as preliminary. Administration of the CAT-SS in larger, high-risk samples would provide more definitive tests of the clinical utility of using adaptive assessment. Confidence intervals for some effects were wide (e.g., CAD-MDD and victimization), reflecting the relatively small number of attempts, and may become narrower in studies that include higher-risk participants. Studies with longer follow-up periods may also reveal other relevant predictors of transitions from ideation to attempts.

Third, we assessed most risk and protective factors with static self-report measures. Results of this and other studies have indicated the incremental utility of adaptive measures. Using CAT methods to characterize other mental health domains, such as anxiety, posttraumatic stress symptoms, psychosis, and substance use, may bolster prediction. Additionally, suicide attempts were measured with items from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System surveys, which may underestimate risk. Use of other validated measures would provide a more comprehensive assessment of suicidal behavior as an outcome. Future research on the CAT-SS could compare its predictive validity with those of other standardized measures, such as the clinician-administered Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (

46). Future studies should explore more longitudinally intensive suicide assessments. The adaptive nature of the CAT-SS and the fact that all the same questions are not repeatedly administered are advantages that could facilitate highly sensitive and precise ecological momentary assessments (e.g., daily or weekly assessments), which are now possible.

Conclusions

The results of this study represent important extensions of previous research and suggest directions for future work. This study is the first to conduct a prospective examination of transitions from suicidal ideation to attempts among SGMY and demonstrates the predictive validity of the CAT-SS. Longitudinal risk and protective factors have been difficult to identify, but our results suggest that the salience of factors may differ for youths with a history of suicidal thoughts. In addition, adaptive testing methods exhibited predictive validity and should be considered for incorporation into screening and intervention efforts.