Public substance use agencies of states and counties are integral to the provision of prevention, treatment, and recovery services for adolescents and young adults (hereafter referred to as “youths”) in the United States (

1). These agencies are involved with implementation of the approximately $290 million in youth-focused substance use federal programing that is allocated by Congress annually (

2) and the $1.8 billion Federal Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant program, which funds services for youths and adults (

3). As such, officials of public substance use agencies are an important stakeholder group to target dissemination and implementation efforts to increase the reach of youth-focused, evidence-based substance use treatments and prevention programs (

4,

5).

Implementation science frameworks suggest that the success of dissemination and implementation strategies could be increased by accounting for the extent to which different youth substance use issues are priorities within these agencies (

6,

7). Such priorities are conceptualized as inner-setting determinants in frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (

8) and the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework (

9). The impact of dissemination and implementation strategies could also be enhanced by taking into consideration the extent to which different external factors are perceived as influencing agency priorities for youth substance use. Such influences are conceptualized as outer-setting determinants in implementation science frameworks (

8–

10).

Recent reviews suggest that inner- and outer-setting factors are frequently measured in research conducted in the settings of public substance use and mental health agencies (

11,

12). Previous research has also assessed U.S. state legislators’ and city mayors’ priorities for public health and the factors that influence these priorities (

13,

14). Although national reports have identified strategies substance use agencies can use to address issues related to youth substance use (

15–

18), no previous research has assessed the extent to which specific issues are perceived as priorities within substance use agencies or as factors perceived as influencing these priorities.

Understanding public agency officials’ priorities for youth substance use and the factors that influence them is important because doing so can inform the selection and tailoring of dissemination or implementation strategies designed for these agencies (

19). For example, a nongovernment organization that conducts training sessions to support the implementation of substance use treatments could develop training materials so that the content, such as specific treatments highlighted or illustrative case studies, is tailored to align with the priorities of substance use agencies. As another example, dissemination materials describing an evidence-based treatment could be tailored to include information about cost-effectiveness if factors related to budget strongly influence priorities or to feature a patient testimonial if patient demand strongly influences priorities (

20). In addition to informing the selection and tailoring of dissemination and implementation strategies, a better understanding of the priorities of substance use agencies could help align researchers’ questions with the practice contexts in which public agency officials make decisions.

This study sought to advance the understanding of the inner-setting priorities and outer-setting influences of public substance use agencies. The study aims were to characterize the priorities of U.S. state and county substance use agency officials for addressing youth substance use, describe the factors that influence these priorities, and assess differences in priorities and influences between substance use agency officials at state versus county levels. We compared responses from officials at these two governmental levels because they may work within different contexts influencing their work.

Methods

We created a contact database of senior-level officials of substance use agencies and directors of youth-focused divisions and programs within these agencies. To this end, we reviewed contact lists maintained by the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and conducted Internet searches. We identified these officials at the state level for all 50 U.S. states and, in addition, at the county level in 15 states that had more decentralized public behavioral health systems, identified as such through consultation with the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. The states used to create the county sample frame were geographically diverse in terms of their U.S. Census region. The West included four states (California, Oregon, Utah, and Washington), the Midwest five states (Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio, and Wisconsin), the South three states (Florida, North Carolina, and Texas), and the Northeast three states (Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania).

A Web-based survey of the state agency officials was conducted between January and March 2020 and of the county agency officials between July and September 2020. The two surveys were identical except for using “state” or “county” language when referring to a respondent’s specific agency. The surveys were approved by the institutional review board at Drexel University. Each agency official was sent a personalized e-mail eight times with a survey link, and telephone follow-up was conducted with state officials to ensure that e-mails were received. Respondents were offered a $20 gift card for survey completion. The survey was sent to 112 state officials with valid e-mail addresses and completed by 42 (response rate=38%) and to 473 county officials with valid e-mail addresses and completed by 80 (response rate=17%). The aggregate sample size was 122, for an aggregate response rate of 21% (N=122 of 585); 35 states had a least one survey respondent.

Measures

The survey presented respondents with a list of 14 youth substance use issues and instructed them to “indicate the extent to which you perceive it as currently being a priority for your agency” on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with 1 indicating “not a priority/beyond scope of agency” and 5 indicating “top priority.” The survey also presented respondents with a list of nine factors and instructed them to “indicate how much influence you think it currently has on your agency’s youth substance use priorities in general.” Possible responses ranged from 1, “no influence” to 5, “major influence.” Similar items have been used to assess factors that influence state legislators’ health priorities (

14). The lists of priority issues and influencing factors were informed by a review of the literature on youths’ substance use and then refined through telephone and e-mail correspondence with former state and county behavioral health agency officials. The order of the items in the priority and influencing factor lists were randomized to reduce the risk for order-effect bias (

21).

Statistical Analysis

Responses were analyzed as both dichotomous and continuous variables. When dichotomized, responses of 4 or 5 were coded as “priority” and “influences priorities.” Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the proportion of respondents who identified each issue as a priority and each factor as an influence. Means and standard deviations were calculated for each item. State and county official data were analyzed together as well as separately. Chi-square and two-tailed independent sample t tests were used to compare differences in responses between the two samples of state and county officials.

Results

Nonresponse analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in the survey response rate by state U.S. Census region within the state agency sample or county agency sample nor by the political party of the state’s governor. The mean opioid overdose death rate among youths ages 0–24 years per 10,000 population was slightly lower in states of those who responded to the survey than in states of nonrespondents in the state agency sample (mean=3.53 vs. 4.59, respectively, t=5.50, p=0.02), but no significant difference in this rate was observed between respondents and nonrespondents in the county agency sample.

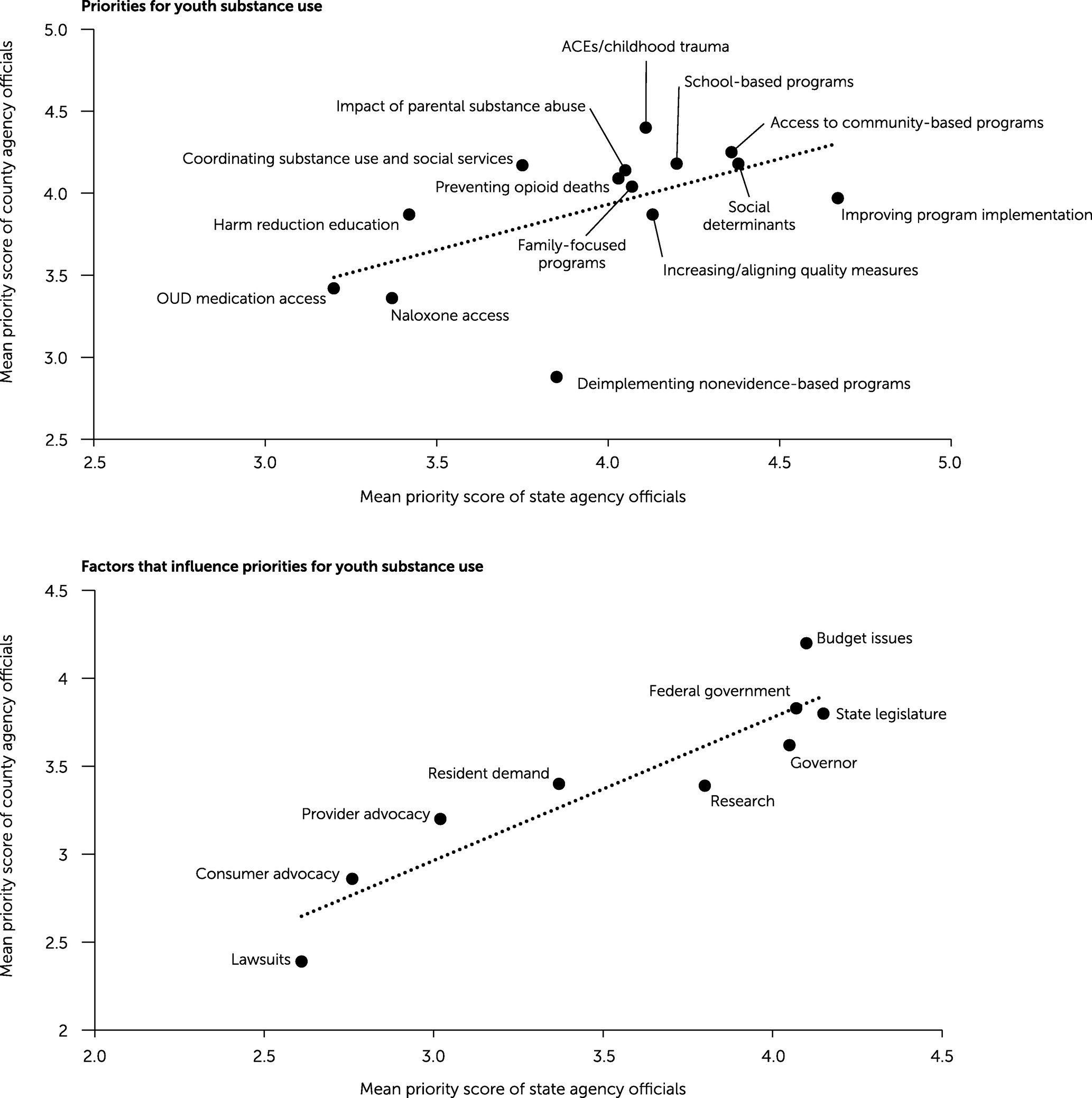

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the proportions of agency officials that identified each youth substance use issue as a priority and each factor as an influence on priorities, respectively, stratified by state and county and for both samples pooled together. The two panels in

Figure 1 indicate the mean priority ratings and influence ratings among state agency officials and county officials. (Tables showing the means, standard deviations, and t test statistics for the priority and influence ratings are available in an

online supplement to this article.)

Priorities for Youth Substance Use

The issues most frequently identified as priorities for youth substance use, identified by ≥80% of the sample, were social determinants of youth substance use (87%), adverse childhood experiences or childhood trauma (85%), increasing access to school-based substance use programs (82%), and the impact of parental substance use on youths (80%) (

Table 1). Increasing access to community-based youth substance use programs was identified as a priority by 79% of the respondents and was the issue with the highest priority rating (mean= 4.29). The issues least frequently identified as priorities, with <50% of the sample identifying them as such, were increasing access to naloxone for youths (49%), increasing access to medications for opioid use disorder among youths (49%), and deimplementing youth substance use programs that are not evidence based (41%).

As shown in

Table 1 and the upper panel of

Figure 1, state and county officials had similar perceptions of the extent to which youth substance use issues should be prioritized. The only exceptions to this were for issues explicitly related to program implementation. Compared with the proportion of county officials, a significantly larger proportion of state identified improving the implementation of evidence-based youth substance use programs as a priority (92% vs. 73%, p=0.01), as well as deimplementing youth substance use programs that are not evidence based (65% vs. 28%, p<0.001). Improving the implementation of youth substance use programs received the highest priority score among state officials, significantly higher than among county officials (mean score of 4.67 vs. 3.97, respectively, p<0.001).

Factors That Influence Priorities for Addressing Youth Substance Use

The factors most frequently identified as influencing priorities for addressing youth substance use, identified by >60% of the sample, were budget issues (80%) and state legislature (69%), federal government (67%), and governor priorities (65%) (

Table 2). The factors least frequently identified as having influence, with <40% of the sample identifying them as such, were provider advocacy organization priorities (34%), consumer advocacy organization priorities (22%), and lawsuits or concerns about litigation (15%). Only about one-half of respondents (53%) identified research evidence as influencing youth substance use priorities.

As shown in

Table 2 and in the lower panel of

Figure 1, similar factors influenced the priorities for addressing youth substance use among state and county officials. A significantly larger proportion of state than county officials identified research evidence as influencing their agency’s priorities (68% vs. 45%, p=0.02). A significantly larger proportion of state than county officials identified state legislature priorities (83% vs. 63%, p=0.02) and governor priorities (81% vs. 56%, p=0.008) as influencing agency priorities for addressing youth substance use.

Discussion

Officials at state and county substance use agencies perceived a range of issues to be high priorities for youth substance use, with upstream causes of substance use, such as social determinants and adverse childhood experiences or childhood trauma, most frequently identified as top priorities. Evidence-supported policy recommendations to address these root causes exist (

22–

25), and our findings suggest that dissemination and implementation strategies that are tailored to include information that helps substance use agency officials address these issues—either directly or through advocating for legislative changes—may be well received. Large proportions of state and county officials also identified improving the implementation of evidence-based youth substance use treatment programs as a priority. This finding indicates that the inner-setting context may be supportive of implementation strategies that help facilitate the delivery of evidence-based, youth-focused treatments in public substance use agencies.

Findings about the issues that are least frequently considered priorities are interesting when considered within the context of youth substance use treatment literature. We particularly note the issues related to opioids. For example, only one-half of respondents identified increasing access to medications for opioid use disorder among youths as a priority. Medication for opioid use disorder among youths is an evidence-based treatment (

26) recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (

27), yet barriers to obtaining access to medication for opioid use disorder among youths exist (

28,

29), and the prevalence of opioid use disorder among youths has been increasing (

30). Furthermore, only one-half of respondents identified increasing access to naloxone among youths as a priority, despite naloxone being a recommended evidence-based intervention and its uptake being low (

31,

32).

In light of these findings, we conducted a post hoc analysis to assess whether the 2019 youth opioid overdose death rate among youths ages 0–24 years in each respondent’s state was correlated with the respondent’s priority rating of each of the three opioid-specific youth issues. We found no significant correlation in the state agency sample nor in the county agency sample. These findings in our sample of administrative policy makers are in contrast to those in studies of state legislators, which indicate that state opioid overdose death rates are associated with these elected policy makers’ opinions about opioid-related issues (

33,

34). Taken together, these results highlight a need to better understand the extent to which opioid-related issues among youths are, or are not, priorities for substance use agency officials.

Only about two-thirds of state agency officials and one-quarter of county officials identified deimplementation of non-evidence-based substance use programs for youths as a priority. Although deimplementation is largely regarded as a priority area among implementation science researchers (

35–

38), it may be a low priority for substance use agency officials because of insufficient workforce or program capacities to meet the need for youth substance use treatment services in the United States (

39,

40). Thus, deimplementing programs might not be a priority because it could exacerbate treatment capacity issues by reducing the supply of available programs. It is also possible that the economic and political costs of deimplementing an entrenched, non-evidence-based program are perceived as exceeding the benefits of deimplementation. Furthermore, it is possible that many respondents did not rate deimplementation of non-evidence-based programs as a high priority because they did not perceive any of their programs to be nonevidence based. All of these possibilities signal a need for future research that explores the determinants of deimplementation in substance use agencies.

The finding that budget issues are perceived as having substantial influence on substance use agency priorities at state and county levels is consistent with those of previous research indicating that information about the budget impact and cost-effectiveness of substance use treatments is of paramount importance to policy makers (

41–

45). Such economic evidence exists (

46,

47), and findings suggest that tailoring dissemination materials to include this information would be beneficial. There could also be a benefit to tailoring dissemination materials to include information about the costs of implementation strategies (

48,

49), especially because improving the implementation of evidence-based youth substance use treatment programs was identified as a top agency priority.

The finding that state legislature and governor priorities have major influences on state substance use agencies’ priorities is not surprising given that these agencies are directly accountable to these entities. However, the finding is still important because it supports the idea that elected officials, such as state legislators and governors, are major outer-setting stakeholders who could be targeted by dissemination and implementation efforts (

10,

41,

42,

45,

50). Dissemination strategies that affect these elected officials’ perceptions of priorities for youth substance use could then influence the priorities and practices of executive branch officials of substance use agencies. The finding that a moderate proportion (53%) of substance use agency officials perceived research evidence as influencing priorities is consistent with results from previous research (

45,

51) and underscores the importance of selecting and tailoring implementation strategies to account for outer-setting contextual factors that influence decision making.

Comparison of survey responses between state and county substance use agency officials revealed more similarities than differences. The most notable difference was that improving the implementation of evidence-based programs and deimplementing non-evidence-based programs were higher priorities among state than among county officials. This finding could reflect county agency officials being more focused on the direct provision of substance use treatments, whereas state agency officials also function in a strategic and planning capacity. However, the difference could also reflect the fact that the state agency survey was fielded immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas the county agency survey was fielded during the pandemic.

Our study had some limitations. The aggregate response rate was moderate for a sample of public agency officials (

52). Although respondents and nonrespondents did not differ in terms of the U.S. Census region of their state or the political party of their governor, the opioid overdose death rate among youths was slightly lower in the states of respondents than in states of nonrespondents in the state agency official sample. However, it is unlikely that this difference substantially influenced the representativeness of the results, because we found no association between state opioid overdose death rates among youths and substance use agency officials’ perceptions of opioid-related youth issues as priorities. Nevertheless, it is possible that agency officials who were motivated to complete the survey systematically differed from those who were not motivated in terms of their perceptions of priorities for youth substance use and the factors that influence them.

The survey asked about the relative priority of 14 youth substance use issues and nine factors that could influence these priorities. By no means were these lists exhaustive inventories of all youth substance use issues that may be perceived as priorities or the factors that influence them. The survey was also limited to substance use agency officials, and a much wider range of public sector agencies, such as child welfare, criminal justice, and education, address youth substance use issues (

53). It should be emphasized that the study focused on substance use agency officials’ perceptions, and therefore the unit of analysis was the officials of substance use agencies, not the agencies themselves. Last, the survey did not assess the extent to which addressing issues of structural racism were priorities. This was a limitation because structural racism is major social determinant that contributes to racial disparities in substance use and mental disorders (

54,

55).

Conclusions

Social determinants of youth substance use, adverse childhood experiences and childhood trauma, increasing access to substance use treatment programs in school and community settings, and the impact of parental substance use on youths were top priorities for substance agency officials. Improving the implementation of evidence-based substance use programs for youths was also perceived as a high priority, especially among state agency officials. However, deimplementing youth substance use treatment programs that are not evidence based was not a high priority at the state or county level. Budget issues and the priorities of state legislatures and governors were factors perceived as having substantial influence on the priorities for addressing youth substance use in public substance use agencies, and research evidence was perceived as having only a moderate influence on these priorities. These survey findings can inform the selection and tailoring of dissemination and implementation strategies to account for the contexts in which officials of public substance use agencies make policy decisions.