Many veterans returning home from deployment face new battles, including unemployment, mental illness, addiction, and problems readjusting to community life (

1,

2). Mental illness can substantially impede a person’s ability to sustain gainful employment (

3–

5). Job loss and financial hardship are associated with high rates of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

6), and prolonged unemployment has detrimental effects on physical (

7) and mental (

8) health outcomes. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) offers a range of vocational rehabilitation (VR) services, including prevocational counseling, sheltered transitional work (TW), and supported employment.

Individual placement and support (IPS) supported employment is a personalized service integrated within a treatment program that assists people with disabilities in obtaining and maintaining meaningful and well-matched competitive employment in the community. IPS is typically reserved for people living with serious mental illnesses, defined as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, and major depression with psychotic features (

9,

10). IPS has demonstrated remarkably robust and consistent employment outcomes (

11,

12), including for persons with disorders other than serious mental illnesses (

13,

14), that are durable over many years (

15).

In 2004, VHA implemented IPS for veterans diagnosed as having serious mental illness; the program provided limited access to veterans with other diagnoses (

16,

17). Subsequent controlled trials confirmed the efficacy of IPS for veterans living with PTSD (

18–

20). Unfortunately, VR or IPS services have been used by fewer than expected veterans with PTSD, traumatic brain injury (TBI), depression, or substance use disorders (

21–

23). Disabled veterans often fear losing disability income benefits or experiencing worsening symptoms in the competitive work environment, which dampens their interest in pursuing employment and engaging in VR services (

24). Additionally, service members transitioning to veteran status often delay seeking mental health treatment, because they fear not being able to obtain employment if psychiatric needs are disclosed—thus potentially delaying much-needed services.

To address these issues, this study sought to evaluate IPS when integrated within a primary care patient-aligned care team (PACT) and offered to veterans with a broad range of nonpsychotic mental disorders. The aim was to offer IPS employment services in a less stigmatizing setting, and it was hypothesized that this arrangement would yield more efficacious outcomes, compared with standard VHA VR services.

Methods

We conducted a randomized, controlled study at the Tuscaloosa Veterans Affairs Medical Center to evaluate the efficacy of IPS when delivered within a PACT, compared with standard non-IPS VR services. The protocol was approved by the Tuscaloosa Veterans Affairs Institutional Review Board, conforming to the Helsinki Declaration. Participants provided written informed consent. Safeguards included oversight by a Data and Safety Monitoring Board and approval of a National Institute of Mental Health Certificate of Confidentiality. Data collection occurred from July 8, 2015, through September 9, 2019. The methods and baseline characteristics of the sample have been described previously (

25).

Eligibility Criteria and Randomization

Prospective participants were referred by their treatment team or were self-referred after seeing a flyer, letter, or brochure that advertised the study or after hearing about the study from another veteran or staff member. Eligible veterans were receiving primary care in a PACT clinic and were age 19 or older, currently diagnosed as having a nonpsychotic mental disorder (including substance use disorders and excluding psychotic, bipolar I, or cognitive disorders), otherwise eligible for VR services (i.e., medical clearance to return to work), unemployed or underemployed (i.e., working ≤20 hours per week in a job not in keeping with the veteran’s ability, aptitude, or skills), seeking competitive employment, not participating in another VR study, not actively suicidal or homicidal, and able to be followed up for 12 months. The initial criteria limited enrollment to unemployed veterans who served after September 11, 2001, but these criteria were relaxed to include the underemployed and veterans who served after 1990.

Eligible veterans were randomly assigned to either IPS or VR by using permuted varied-sized block design. Participants, providers, and outcomes assessors were openly aware of the postrandomization assignment.

Baseline Assessments

A clinically experienced research coordinator (C.M.B.) collected baseline demographic data and assessed the participant with the structured MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) for

DSM-IV diagnoses (

26) and the Ohio State University Traumatic Brain Injury (OSU-TBI) identification method (

27,

28). The MINI and the OSU-TBI have previously well-established interrater reliability and predictive validity (MINI, all κ values ≥0.75 and excellent positive predictive value; OSU-TBI, all κ values ≥0.60; intraclass correlations >0.80; predictive validity, p<0.006).

Interventions

The IPS intervention (

29) used a rapid job search to help veterans obtain a broad diversity of jobs, assisted participants to directly engage in a competitive job rather than in prevocational training or set-aside sheltered jobs, embraced the notion of “zero exclusion,” provided personalized information about government entitlements, utilized a network of employers developed by the IPS specialist on the basis of veterans’ interests, and provided individualized follow-along supports that were open ended. The IPS model was not deliberately changed; however, implementation in a new setting required some adaptations as to how the colocated IPS specialist connected with the providers. Instead of participating in regularly scheduled comprehensive treatment team meetings as would be typical of IPS for populations with serious mental illness, the IPS specialist participated in brief PACT huddles, gave updates at monthly staff meetings, and met individually with providers for brief discussions, as clinic schedule permitted.

Available as an existing service within the medical center on a consultation basis and not embedded in PACT, the standard VR (control group) offered compensated work therapy (CWT); TW assignments in a set-aside, minimum-wage, time-limited job; or CWT–community-based employment services (CBES), which involved limited community job search and placement. The TW work assignments were typically low-skill jobs within the local VHA setting and aimed to help participants gain work-hardening experiences before they obtained competitive work in the community. Standard VR specialists had minimal contact with PACT providers, and follow-up supports for those receiving VR services ended soon after the TW assignment was completed or their first job was acquired.

In keeping with the IPS practice, an IPS expert (R.T.) provided technical assistance to the IPS specialists via biweekly teleconferences and quarterly onsite meetings and conducted semiannual onsite IPS fidelity-monitoring visits with performance improvement feedback. Standard VR services were also evaluated with this scale to ensure that there was minimal overlap of VR and IPS. Day-to-day supervision of the IPS and VR specialists was provided by the onsite VHA vocational service manager.

Employment Outcomes

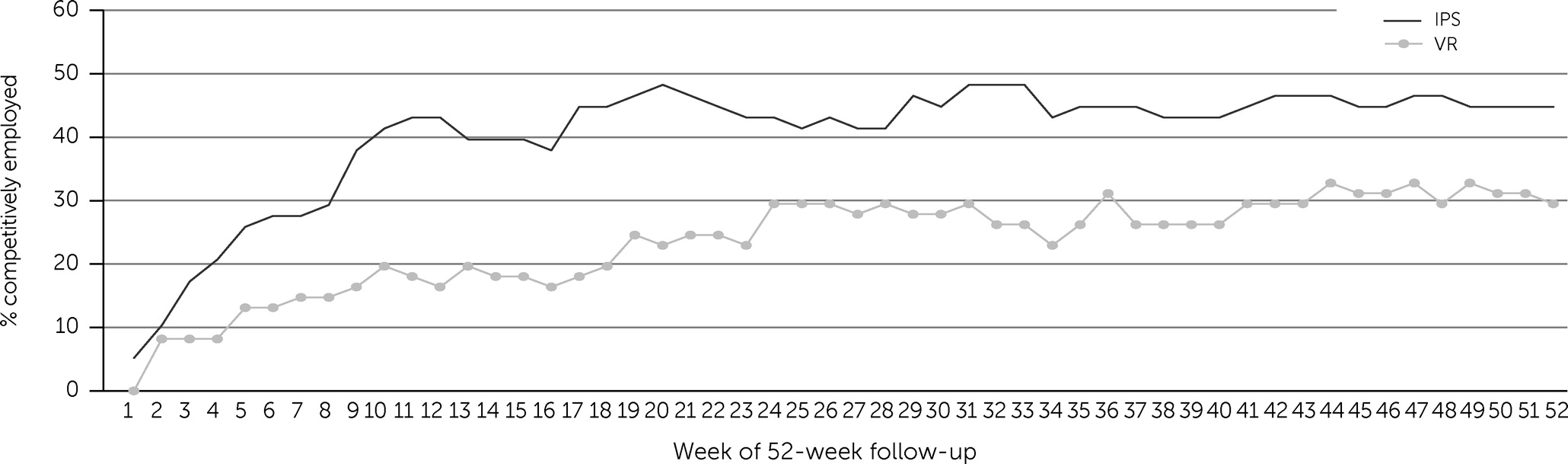

Postrandomization outcome assessments occurred monthly over 12 months. On the basis of a self-report employment calendar diary, pay and tax documents, and medical records, the research coordinator (C.M.B.) assessed each week for the following: work for pay (yes, no, or unknown), type of work (competitive, TW, or other), type of job(s), number of days and hours worked, gross income earned, and whether the job was new. “Competitive” was defined as a job for salary, wages, or commission in a setting that was not set aside (i.e., same job could be held by someone without a disability), not transient (i.e., yard work, babysitting, or day labor), and not military drill. “Steady worker” was defined as employed for ≥26 weeks of the 52-week follow-up, and “employed” was defined as working in a competitive job for ≥1 hour per day for ≥1 day per week. Weeks did not have to be consecutively worked to count toward the threshold of “steady worker.”

Statistical Analyses

The primary hypothesis was that IPS would result in a greater proportion of steady workers, compared with standard VR. The primary analysis used a logistic regression model to calculate an odds ratio (OR), controlling for baseline variables where relevant. The proportion of weeks worked in a competitive job unencumbered by a TW assignment was compared between groups, thus controlling for the time in a sheltered work setting. For purposes of outcome analyses, missing data for weeks worked were counted as “not worked.” However, missing data were minimal and did not have a statistically significant effect on our outcomes. The analysis adhered to the intent-to-treat principle, and participants were retained in the arm to which they were randomly assigned for the follow-up period, even if they discontinued the intervention or exited early. Secondary analyses of the employment outcomes included total time worked, income earned from competitive sources and all sources, and type of jobs held. These continuous employment outcomes were compared by using an independent, two-tailed t test, and categorical outcomes were analyzed by using the chi-square distribution or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate IPS in a primary care setting for people with a broad range of nonpsychotic mental health conditions. IPS efficacy research has traditionally focused on individuals with serious mental illness within a mental health clinical setting, with recent expansion to other diagnoses, such as PTSD (

19), TBI (

31), and spinal cord injury (

32). However, like civilians, veterans have a broad range of nonpsychotic mental conditions that can interfere with maintaining a job, and they often initially present for treatment in a primary care setting. To overcome stigma related to being referred to a mental health clinic and the delays in access due to the referral and intake process, we innovated delivery of IPS by providing services directly within primary care clinics and including veterans with a broad range of nonpsychotic mental disorders. This allowed for more efficient delivery of IPS services to an expanded population.

Compared with standard non-IPS VR services, IPS led to a substantially greater number of steady workers in a much shorter time frame, which resulted in more full-time jobs and higher income earned. Research has consistently shown that IPS is efficacious in helping participants return to work (

11,

13) and improves psychosocial recovery (

20). Our results are consistent with those of a multisite study of veterans with PTSD, which found that IPS participants were more rapidly able to obtain employment and were twice as likely to maintain steady work, compared with those receiving usual-care VR services (

19). Meaningful employment embraced by strong clinical supports contributes to health and well-being and serves as an antidote to social exclusion (

11).

Despite decades of public health education, the stigma associated with mental disabilities is particularly rampant in the workplace and causes delays in seeking mental health care, especially for members of the military (

33). Therefore, the delivery of IPS within primary care has the potential to accelerate access to effective employment services in which people would otherwise not engage for fear of being stigmatized during the employment process. There is growing evidence that individuals with nonserious mental health issues are more likely to be treated in primary care than in a specialized mental health clinic (

34). PACTs are already providing individualized, patient-centered, and evidence-based behavioral health services; thus, with more research to refine high-fidelity implementation, IPS could be added to the PACT armamentarium. This strategy is in line with the VHA Mission Act (

35) and whole-health initiatives that aim to increase access to a full array of services for veterans both in the VHA and in community settings.

Implementation of IPS in a new setting required a steep curve of adaptation for our PACT providers, because some elements of IPS were not easy to implement, such as demonstrating an advanced understanding of the IPS principles by executive leadership and clinicians and integrating the IPS specialist into a fast-paced PACT. As reflected in the fair fidelity scores, the PACT team struggled with the core principle of IPS integration as it related to shared decision making, given the limited time that the primary care providers had available. Unlike other initiatives for persons with serious mental illness and for those with PTSD, where the IPS specialists work intensely with a mental health team, the PACT model did not allow for ease of access to the interdisciplinary team in which employment considerations were included within the overall treatment plan. This dynamic resulted in a greater burden on the IPS specialist to address case management and social work issues rather than focused employment services. Our IPS team was small, and the onsite supervisor was transitioning full retirement, which negatively affected the IPS fidelity score—i.e., higher points are given for one or more specialists and for a highly engaged VR supervisor. The IPS staff turnover required training and reintegration of new specialists, which likely affected implementation from the standpoint of sustained strategic job and employer development, consistency in establishing community connections, and maintenance of the network of employment resources. The IPS specialists had difficulty at times promoting a diversity of jobs within the community and leveraging the vocational assessment as a dynamic tool for veteran engagement and strategic job development. Ideally, study teams should allow time for IPS to reach a more mature state of implementation prior to starting randomization—although research budgets do not always allow for this luxury of time and readiness. However, within the constraints of any budget, the leadership and clinicians should be fully engaged and strongly advocate for high-fidelity IPS implementation in a new setting to achieve maximal outcomes.

The findings of this study are timely, in that the COVID-19 pandemic has put steady employment in jeopardy, as evidenced by a 12% increase in veteran unemployment (

36,

37). Large-scale national crises that lead to economic recessions and increased unemployment are associated with adversities, such as increased risk of overdose and suicide (

38,

39). Strengthening community partnerships and increasing services available to veterans outside traditional settings have the potential to improve timely delivery of efficacious services, mitigate negative health outcomes, and improve psychosocial functioning.

The study had strengths and limitations. The strengths included its randomized approach, 12-month follow-up period, broad eligibility criteria, and novel setting. The generalizability of the findings is limited by a single-site design in a sample of mostly male veterans; thus, results would require replication from a multisite, more diverse, and larger sample of participants to better understand the efficacy of IPS in PACT. Limitations of the study include the fair fidelity to the IPS model, which may have weakened employment outcomes in the intervention group. In addition, the TW assignments may have delayed entry into community-based competitive work, which may have weakened employment outcomes in the control group. However, we confirmed that, despite fluctuations in fidelity of IPS implementation and the fact that half the control group participated in a time-limited TW assignment, IPS resulted in a significantly greater proportion of weeks employed (40%), compared with VR (25%), when the analysis controlled for the number of weeks encumbered by a TW assignment.