Twenty-one percent of individuals who are homeless have serious mental illness, compared with 5% in the general U.S. population (

1–

4). Mental illness among people who are homeless is associated with higher risk for mortality, disability, substance use disorders, and suicide (

5–

8). Adverse living conditions, combined with serious mental illness, substance use, trauma, and feelings of disaffiliation, can diminish the ability of people who are homeless to manage their general medical and mental health (

9–

13). Among individuals with serious mental illness, homelessness is associated with higher rates of emergency and mental health service utilization and law enforcement involvement (

14–

17). The pervasive cycle routing homeless people with serious mental illness from hospitals, to jails, and to the streets rarely results in resolution of housing and mental health needs (

16). This revolving door of service systems for homeless individuals often involves involuntary psychiatric treatment.

In California, involuntary psychiatric treatment is governed by the Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) Act, which was enacted in 1967 with the goal of ending “the inappropriate, indefinite, and involuntary commitment of persons with mental health disorders” (

18,

19). Under the LPS Act, temporary civil commitment for psychiatric treatment is authorized for individuals with serious mental illness who meet specific criteria—danger to self, danger to others, and/or grave disability. When certain criteria are met, sequentially longer commitments are possible: up to 72 hours for assessment, evaluation, and crisis intervention (Welfare and Institutions Code [WIC] 5150); up to 14 additional days for those who still meet criteria for involuntary psychiatric treatment at the end of the 72-hour period (WIC 5250); and up to 30 days of additional intensive treatment for individuals who continue to meet criteria for grave disability and are unwilling to accept treatment voluntarily (WIC 5270) (

19–

21). In everyday practice, these commitments are referred to as 72-hour, 14-day, and 30-day holds.

In California, an estimated 24% of emergency medical service encounters are for involuntary psychiatric holds (

15). Nearly 40% of these involuntary holds are attributed to a very small number of patients who have five or more repeated holds and grave disability, a population that frequently includes homeless people (

17). In theory, patients may move through the system of sequentially less restrictive mental health services after hospitalization in order to transition to community-based care. Potential discharge locations include locked and unlocked residential facilities (e.g., institutions for mental disease, psychiatric rehabilitation, and board and care) that offer a structured living environment with onsite mental health services. However, severe shortages of mental health beds at all levels of inpatient and residential care in California and persistently high rates of homelessness and mental illness in California mean that frequent short-term involuntary holds do not always resolve housing instability or mental health needs (

16,

22).

The LPS Act also established criteria for initiating an LPS mental health conservatorship (

23). LPS conservatorships last for 1 year and are reserved for individuals with grave mental disability and who require long-term assistance for making health decisions (

23). Unlike multiple short-term holds, LPS conservatorships mandate long-term, intensive mental health services that can be coupled with placement in long-term, locked residential facilities (

23). Although conservatorships are necessary for some individuals, they are contentious, have had mixed success in resolving long-term mental health and social needs of homeless individuals with grave mental disability, and are burdensome to mental health systems. Evidence suggests that rates of recidivism (jail, homelessness, emergency service use, psychiatric hospitalization) are high when individuals exit conservatorship and that a minority of those conserved can function independently (

24,

25).

Evidence indicates that individuals who are homeless and have grave mental disability frequently use psychiatric services via short-term LPS holds, but less is known about how homelessness and LPS mechanisms, including LPS conservatorship, intersect to affect mental health service systems (

26). Initiating an LPS conservatorship is a difficult, lengthy, and resource-intensive process for referring facilities, including varying timelines, petitions, court hearings, and other requirements by the patient’s county of residence as well as renewal of the conservatorship every year (

25). The purpose of this study was to examine the association between homelessness and length of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization under LPS mechanisms in California and to explore the role of the LPS conservatorship in determining discharge location for homeless patients with grave mental disability.

Methods

Design

This retrospective, observational study used data from a nonprofit safety-net psychiatric hospital in Los Angeles from 2016 to 2018. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the research committee at Gateways Hospital and Mental Health Center.

Setting and Sample

The setting for this study was a 28-bed adult (18–56 years) inpatient unit at a safety-net psychiatric hospital near Downtown Los Angeles. The hospital primarily cares for adults who are placed on an involuntary psychiatric hold and who do not have health insurance. Psychiatric hospitalizations for uninsured patients are paid for by the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health through the Short-Doyle program, a fund established by the State of California Short-Doyle Act of 1953, or by other county funds for psychiatric emergency services (

27).

A total of 849 adult patients (18–56 years) were admitted to the hospital between January 2016 and December 2018. Patients with no recorded discharge data, patients who were accepted for admission but did not actually arrive at the facility, patients sent back to the admitting facility on arrival, and a small number of patients who were hospitalized under one of two non-LPS mechanisms (voluntarily admitted patients, forensic patients) were omitted from the sample (N=54). Ultimately, 795 patients were included in the analysis.

Data

Hospital administrative data and medical records data were used for this study. Administrative data were from an internal patient tracking data system that included length of stay, type of admitting facility (safety-net hospital, psychiatric urgent care, other), funding source (Short-Doyle funds or psychiatric emergency service funds), discharge location, age, gender, and dates of LPS legal proceedings during hospitalization (e.g., initiation of a new involuntary hold, probable cause hearing, initiation of conservatorship). Homelessness status at the time of admission was extracted from admission notes in patient medical records.

Variables

The primary outcomes for this study were length of stay (days) and whether or not the patient was unhoused at discharge. The primary predictor variables were homelessness status at admission and whether conservatorship was initiated during hospitalization.

Predictors.

Homelessness status at admission was indicated in admission notes as routine practice because the hospital consistently receives a high volume of people who are homeless. Although homelessness can refer to a range of unstable living situations, for this facility “homeless” denotes that the patient was brought to the facility from living on the streets, not from shelters or unstable housing with relatives or friends.

Conservatorship initiation status was determined from conservatorship proceedings dates in the administrative data set; patients were coded as having been conserved if a temporary conservatorship was initiated. Within the California LPS system, grave disability criteria are required to be met for 30-day holds and conservatorship initiation (

23). Because patients can be placed on a 14-day or a 30-day hold or be conserved—in that sequential order—only if they have acute, ongoing, unresolved psychiatric need and grave disability, hold status at discharge was used as an indicator of psychiatric severity.

Outcomes.

Length of stay in days was calculated from admission and discharge dates. Discharge locations were categorized into four types: home (patient’s, family member’s, or friend’s home), locked psychiatric residential facility (e.g., institution for mental disease, psychiatric rehabilitation), unlocked psychiatric residential facility (e.g., step-down institution for mental disease, board and care, group home), and unhoused (e.g., homeless shelter, short-term transitional housing, hotel or motel, patient escaped hospital site without returning).

Analysis

Analyses were performed by using R, version 4.0.3 (

28). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study sample overall and were stratified by homelessness status at the time of admission. Bivariate tests (analysis of variance for continuous variables, chi-square tests for categorical variables) were used to compare patients who were homeless at admission with all other patients, with a Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons.

The association between homelessness status at admission and length of stay was assessed with a multiple linear regression model regressing length of stay on an indicator for homelessness status at admission and adjusting for patient age (years), patient gender (male, female), and admission year (2016, 2017, or 2018). Next, the association between conservatorship initiation and discharge status only among patients who were homeless at admission (N=362) was assessed by using multiple logistic regression models with each of the four discharge location variables (outcomes) regressed on the categorical variable for the highest-level hold during the psychiatric hospitalization (predictors). This predictor variable had four categories indicating that the highest level of involuntary commitment was, in reverse sequential order, conservatorship (the predictor of interest) or a 30-day, 14-day, or 72-hour hold. The 30-day-hold category was used as a reference because it is the final hold category prior to conservatorship initiation. The association between highest-level hold and discharge location among individuals receiving conservatorship was therefore relative to those whose highest-level hold was for 30 days. This categorical highest-hold variable was treated as a proxy for length of stay and psychiatric severity as well as for assessing the specific implications of conservatorship. The model was adjusted for the same covariates noted above.

Results

The percentage of patients who were homeless at admission increased from 45% (N=128) in 2016 to 49% (N=145) in 2018. The average length of stay for adult patients from 2016 to 2018 was 25.6 days (median=11 days, range 0–483 days). Most patients stayed for fewer than 14 days, but the average length of stay was 2.5 times longer for patients who were homeless at admission compared with patients who were housed at admission. Conservatorship was initiated for 14% (N=50) of the 362 patients who were homeless at admission and for 3% (N=11) of the 433 patients who were not homeless. Homeless patients for whom conservatorship was initiated comprised 6% (N=50) of the overall sample, but their hospital stays accounted for 41% of total inpatient days. The average length of stay for patients for whom conservatorship was initiated was 154.8 days. Most homeless patients for whom conservatorship was initiated were male (N=38, 76%), and patients under conservatorship had a mean±SD age of 37.5±11.3 years.

Patients who were homeless at admission, on average, were older (p<0.01), were more often men (p=0.01), and more frequently met criteria for initiation of conservatorship (p<0.01), compared with those who were not homeless (

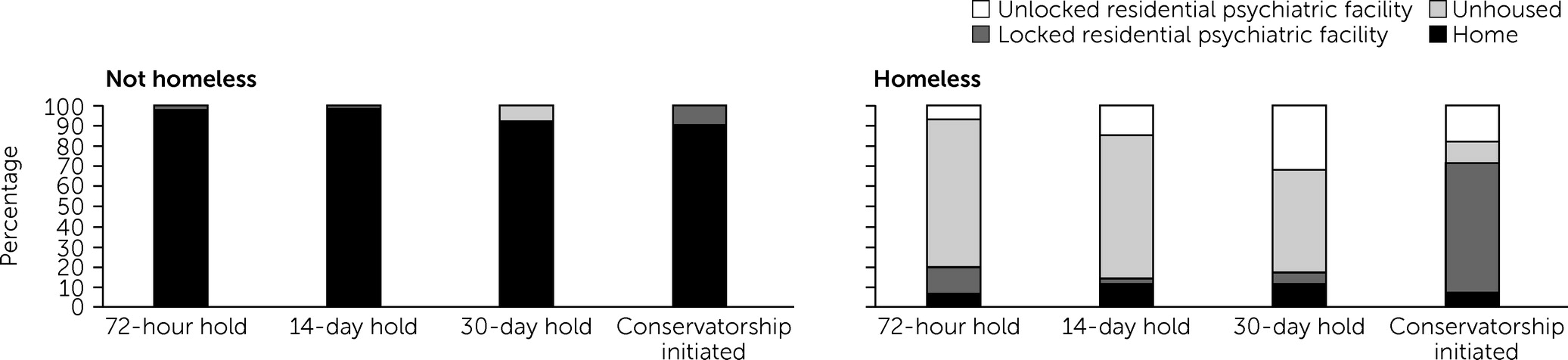

Table 1). They were also more frequently unhoused at the time of discharge (p<0.01). Fifty-six percent (N=203) of patients who were homeless at admission were unhoused at the time of their discharge, compared with 2% (N=9) of nonhomeless patients. Among patients who were homeless at admission and had a conservatorship initiated during hospitalization, 8% (N=4) were discharged to home, 64% (N=32) were discharged to a locked psychiatric or residential facility, 18% (N=9) were discharged to an unlocked psychiatric or residential facility, and 10% (N=5) were unhoused at the time of discharge (

Figure 1).

In the first model predicting length of stay (

Table 2), homelessness status at admission was associated with longer length of stay after adjustment for sociodemographic variables. Being homeless at admission was associated with an additional 27.5 days of hospitalization (SE=3.5 days, p<0.001). Older age was also associated with longer hospitalization (p<0.01).

Among the subsample of patients who were homeless at admission (N=362), those who had a conservatorship initiated had 11 times the odds of discharge to a locked residential psychiatric facility compared with those whose highest hold type was a 30-day hold (

Table 3). This subsample also had a substantial reduction in odds of being unhoused at the time of discharge (risk ratio [RR]=0.19). Other gradations in highest hold type during the hospitalization were also associated with differences in discharge location: those who had a 14-day hold as their highest hold had a large reduction in odds of discharge to an unlocked psychiatric residential facility (RR=0.46) and a 1.4 times greater odds of being discharged unhoused, relative to those with a 30-day hold as their highest hold type. Among those who were homeless, younger age had a small but significant association with being discharged to home. Being admitted during the most recent year in the data set, 2018, was also significantly associated with discharge to an unlocked psychiatric residential facility and with a reduction in the likelihood of being unhoused at the time of discharge (

Table 3).

Discussion

This study of involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations in Los Angeles found that patients who were homeless at the time of admission experienced longer hospitalizations and were more likely to remain unhoused when discharged than those who were not homeless (

26,

29–

31). Among patients who were homeless at the time of admission, those for whom an LPS conservatorship was initiated were less likely to be unhoused at time of discharge than those who were discharged after a 30-day hold, and a majority of conserved patients were mandated to a locked residential facility (e.g., institution for mental disease or psychiatric rehabilitation), where their mental health care could be continued (

23). Such discharges are common in California for individuals in conservatorship, who require a highly structured environment (

24). It is important to note that being placed in a locked residential facility is not equivalent to being stably and voluntarily housed at the end of inpatient treatment. Although psychiatric hospitals expend substantial resources in retaining patients with serious mental illness until they are able to be placed in an appropriate lower level of treatment that includes housing, there is no guarantee that patients will remain housed after exiting their conservatorship (

32,

33).

Patients who were homeless at admission and had a conservatorship initiated during hospitalization represented 6% of the sample but 41% of inpatient days. This substantial allocation of inpatient resources was due in part to a scarcity of beds within lower levels of care (i.e., institutions for mental disease) (

33,

34). Patients who are placed in conservatorship can remain in an inpatient setting for 3–6 months, sometimes for more than 1 year, while awaiting bed availability in locked residential facilities. Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization at a community-based hospital is estimated to cost $767 per day, or $279,802 per year, in contrast to the estimated $13,661 annual cost of a year of supportive housing (

35,

36). In addition to the fact that inpatient facilities may be too restrictive for patients who are conserved and stabilized psychiatrically, the immense amount of inpatient resources that must be devoted to conserved patients awaiting placement means that inpatient psychiatric hospitals cannot function as intended to stabilize acute psychiatric crises (

34). The high number of inpatients under conservatorship means that fewer remaining beds are available for others needing acute psychiatric care, which may affect the length of stay and discharge dispositions of these other patients.

In 2020, an audit of the implementation of the LPS Act was conducted in three California counties (

22,

34). The report concluded that all three counties failed to ensure adequate care for people with serious mental illnesses and that repeated involuntary holds did not result in connection to community-based care (

34). Our findings from one of the few facilities in Los Angeles County that cares for individuals without insurance who are placed on involuntary holds, which often includes homeless people, align with the conclusions of the report. Our findings also suggest that reliance on conservatorships as a means to secure both longer-term shelter and mental health treatment is a signal of systemic gaps in California’s safety-net systems of care (

33,

34,

36,

37). Although, in theory, homeless individuals with grave disability from serious mental illness have a continuum of available housing and mental health treatment options that do not involve being compelled into restrictive treatment, jails and prisons, or the streets, extremely limited bed availability prevents seamless care transitions along this continuum (

38). Hospitals in California often must discharge patients unhoused or mandate patients to restrictive settings, with no alternatives in between (

32,

34,

39).

Although conservatorship can be a necessary mechanism for assisting people with grave disability from serious mental illness to receive treatment, it is important to note that conservatorship is not appropriate or humane for a majority of people with serious mental illness who are homeless, particularly when extended stays in an acute setting are needed to accommodate legal processes and residential placement. California can expand upon existing services (e.g., Homeless Outreach and Mobile Engagement, Housing for Health) and can draw lessons from other locales to expand the continuum of housing and mental health treatment options available to individuals with serious mental illness who are homeless (

39–

43). For example, in Los Angeles, homeless-outreach teams are in place to connect homeless persons who do not utilize traditional models of care to street-based medical and psychiatric providers (

44,

45). Because patients with severe mental illness and chronic homelessness are sometimes too functionally impaired to engage in treatment and placement, empowering street-based teams with the ability to provide street-based treatment and initiate LPS conservatorship referrals may help reduce the burden of prolonged hospitalizations in current LPS conservatorship pathways (

46,

47). Increased construction and funding of Housing First permanent supportive housing and expedited pathways to access such services outside the hospital setting may also help reduce the burden of prolonged hospitalizations associated with this vulnerable population. There is a need for more systematic and comprehensive data regarding conservatorship and long-term outcomes (e.g., medication adherence, suicide, quality of life, hospital readmissions, housing, violence) of civil commitment (

25). County or state mental health systems may be well suited to collecting such data to improve the use of these legal pathways and ensure appropriate service coordination for individuals who are conserved.

This study had strengths and limitations that should be considered in interpreting the results. Our study used data from a patient population that is transient and at times difficult to access for research purposes. We had a large sample from this population and information about legal proceedings during hospitalization under the LPS Act. Our study also had detailed information about discharge location and type. There were limitations to our study as well. The study used a sample from a single facility, and we did not have detailed information on past mental health history (past involuntary holds, hospitalizations), psychiatric diagnoses or symptoms, race-ethnicity, or comorbid medical conditions. Additionally, we did not have long-term follow-up data on patient housing status. All patients in the sample were hospitalized, and we were unable to make comparisons with other mental health programs that initiate conservatorships (e.g., assisted outpatient treatment) or to homelessness service programs that initiate housing. Future studies should investigate the health and social history and long-term outcomes of this population, including consistency in psychiatric and demographic characteristics of those for whom conservatorship is initiated and who remains stably housed in the long term.

Conclusions

The intersection of homelessness and mental illness presents a major challenge to California, which has both a housing crisis and substantial gaps in safety-net mental health services (

4,

34,

36). This study illustrates how LPS conservatorships function in such a context. They reduce the likelihood of patients being discharged to the streets but also can deplete mental health resources in inpatient settings. Conservatorships require substantial resources from hospitals and do not guarantee that an individual will be connected with housing when exiting conservatorship, but conservatorships can benefit some patients with grave disability from serious mental illness by allowing them to receive intensive treatment in settings that include residence. These findings suggest a need to expand psychiatric services along the continuum of psychiatric care, including street-based care, and to study factors associated with resolution of long-term housing and mental health needs for individuals who are conserved, which can then inform future intervention research.