Adolescence (i.e., ages 10–19 years) is a peak time for the development of behavioral health issues, including mental health and substance use problems. Indeed, behavioral health treatment accounts for the largest proportion of health care spending for children and adolescents (

1). Youths often experience recurrences of behavioral health symptoms, suggesting the need for treatment across the course of adolescence rather than time-limited care. Similarly, extensive evidence indicates that both internalizing (e.g., depression and anxiety) and externalizing (e.g., attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD] and behavior disorders) problems that start in childhood can persist through adolescence (

2,

3). Recent research has more closely examined patterns of depression and anxiety among youths and adolescents and reported that such problems typically follow an episodic course and that recurrences and relapses are common; for example, among community and clinical samples of youths, 50%–70% of those with depression experienced recurrence within 2–3 years of the index episode (

4). Externalizing problems such as ADHD are also likely to persist throughout childhood and adolescence (

5). Despite the recurrent and episodic nature of behavioral health problems, much of the literature on behavioral health treatment focuses on single courses of psychotherapy interventions (

6); less is understood regarding long-term trajectories of behavioral health care among adolescents. In this study, we examined outpatient psychotherapy utilization to identify population-wide service utilization patterns across a period in which behavioral health symptoms are likely to recur.

In some studies (

6–

9), researchers examined patterns of behavioral health service utilization among youths in the United States; however, most of these studies are dated, only examined a narrow window of time, and relied on self-report data to determine rates and patterns of service utilization. In one study, Saloner et al. (

10) attempted to define episodes of mental health care and to examine patterns of treatment utilization and episodes of care among a large sample of U.S. youths across a 2-year period to better illustrate how youths do not follow a linear trajectory or single episode of care. Consistent with results from previous studies, they found low rates of both treatment utilization and continuity of care over a 2-year period, with an average duration of <6 months and with 40% of youths having only one mental health visit (

10). However, the authors used survey data to examine a wide variety of mental health services, and almost 40% of the participants were lost to attrition (

10).

In some studies, researchers have used administrative data to more accurately examine patterns of behavioral health care utilization by youths and to identify unique care trajectories. In one study, Reid and colleagues (

11) used an administrative data sample of Canadian youths and identified five distinct patterns of service use defined by duration of service involvement, service frequency, and defined episodes of care. Such findings illustrate the heterogeneity in patterns of care among children and adolescents ages 5–13 years; specifically, some in this age group receive multiple episodes of care, whereas others engage in only single episodes of care with varying duration and intensity. Still, these findings are based on a sample of Canadian youths; given the unique complexities of the U.S. health care system as well as the dynamic nature of child and adolescent developmental stages, it is important to determine whether these findings extend to other samples, such as U.S. adolescents.

This study expands on previous research to better understand patterns of outpatient psychotherapy utilization among adolescents in the United States. In this study, we focused on a large sample of adolescents enrolled in Medicaid; 51% of U.S. youths were enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) (

12). Thus, a better understanding of outpatient psychotherapy utilization among adolescents in this large group is needed. We focused on the course of outpatient psychotherapy utilization because this modality is the most commonly used service compared with higher-intensity behavioral health services, such as inpatient or residential services. Moreover, ongoing outpatient services are used, in part, to prevent more intensive (and higher-cost) services; therefore, it is important that youths with behavioral health needs receive appropriate and consistent services (

13,

14).

Discussion

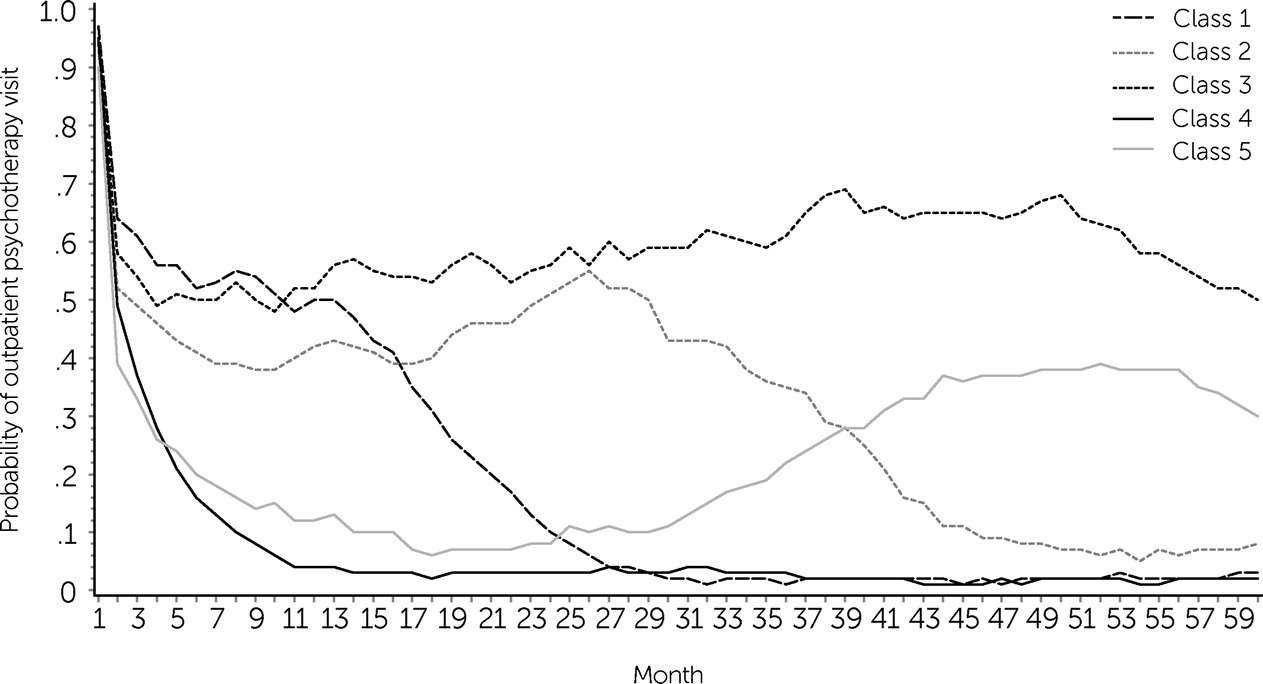

In this study, we sought to examine patterns of outpatient psychotherapy utilization among a large sample of adolescents during a 5-year period. In this large sample, five unique patterns of service utilization were identified that could be characterized by differences in duration of involvement and level of engagement as well as by differences in rates of diagnoses and demographic characteristics. The largest class (38.7% of the sample) was characterized by adolescents with minimal service use (classified as nonuse); this class had a psychotherapy visit of on average <1 month per year, had the highest percentage of Hispanic or Latinx adolescents, and had the longest duration of Medicaid enrollment gaps. One class, characterized as late-onset low engagement, had the highest rates of ED and inpatient behavioral health visits in the first month. Two classes were characterized by service utilization immediately after the initial visit for the first 3 years before a drop in utilization: one class of individuals with high engagement followed by a significant drop in engagement after year 2 and another class with variable and moderate engagement during the first 3 years. The smallest class of individuals were those with continuously high engagement throughout the 5-year window; this class had the highest percentage of adolescents with developmental disorders.

It is well understood that different behavioral health problems require specific treatment approaches with varying courses and service intensity (

9,

17). In this study, we focused on the use of psychotherapy services in particular, and our results suggest that symptoms are not always “cured” after a single course of manualized treatment; this conclusion is inconsistent with much of the research on adolescent behavioral health treatment that focuses on symptom changes across a time-limited standardized course of manualized treatment (

6,

18,

19). Moreover, there is evidence for a subset of “high-cost” outpatient service users with multiple and more complex diagnoses (

17). Although the data did not account for problem severity, results indicating different patterns of service use and differences in prevalence of diagnoses across classes do suggest that severity is a subgroup-differentiating feature. For example, the continuously high engagement class had the highest rate of developmental disorder diagnoses, and although we note significant heterogeneity in the severity of symptoms and level of functioning within and across these diagnoses, this general diagnostic class is associated with more intensive and high-cost services (

17). Taken together, our findings underscore the need for additional research to consider trajectories of behavioral health problems across this dynamic developmental period to inform best practices for managing such problems as well as informing health care policy so that appropriate access to treatment is available.

Most adolescents in the study fell into the nonuse class; this observation is consistent with findings that the near majority of youths do not engage in or do not seek needed psychotherapy services and that continuity of care and treatment engagement is challenging (

7,

10,

11,

20). This study is one of the first to examine long-term trajectories of care among a large sample of Medicaid-insured adolescents. Other studies based on samples of privately insured youths in the United States have also shown high rates of early treatment termination or lack of continuity of care (

7,

10). However, in one recent study, lower rates of treatment utilization were found among adolescents with Medicaid compared with those with private insurance (

21). Thus, further research is needed to better understand potential differences in service utilization by health insurance type. The nature of the data used in the present study did not allow for exploration of reasons for low utilization; however, previous literature has highlighted family preferences (

22), patient-provider relationships (

23,

24), geographic access to care (

25), and system-level variables (i.e., poor care coordination) as reasons for poor care continuity. Taken together, the findings underscore the need for efforts to increase service utilization through improved service connection, such as through utilization of integrated care models (

26), treatment engagement strategies, and treatment retention.

We also noted differences in demographic characteristics across the classes we identified that are consistent with previous findings. For example, the nonuse group had the highest percentage of Hispanic or Latinx adolescents, consistent with previous findings of lower service utilization among minority youths (

10,

27–

29). These findings highlight the need for health care policy to address such disparities. With respect to psychotherapy in particular, extensive research is available on the need for cultural adaptations to evidence-based interventions (

30,

31); although this premise could not be deciphered from the data, results hint at the need to further explore whether implemented treatment models are culturally appropriate, because recent meta-analytic results suggest that culturally adapted interventions are associated with greater symptom reduction and better retention in treatment (

31,

32).

We note several limitations of this study. The study data were limited to Medicaid claims, and reasons for nonenrollment were unknown. Furthermore, significant policy changes occurred between 2006 and 2017, such as Medicaid expansion, that could have affected patterns of service use. The data were from Indiana, which did not expand Medicaid until 2015; therefore, in future analyses with more recent data, researchers should examine changes in utilization due to Medicaid expansion. Given that the data were from an urban county in one state, results may not be generalizable to other areas. Heterogeneous and dynamic patterns in Medicaid eligibility and enrollment change that can occur monthly (i.e., “churning”) also make it challenging to delineate large classes of adolescents on the basis of whether drops in service use were due to Medicaid enrollment or another reason. Data reported in the LCA models were only for outpatient psychotherapy visits because this service area was the focus of this article; further research is needed to examine use of inpatient, ED, and residential services. Similarly, the data did not account for medication management services given that psychotherapy is different from medication treatment alone; in future studies, researchers should examine use of medication and psychotherapy (

21). Last, because of the aforementioned data limitations, we were unable to account for the severity of adolescents’ behavioral health problems; however, as mentioned above, other studies have identified a link between type and severity of problems and patterns of service utilization (

10,

11,

16). In future studies, researchers should further examine differences in utilization on the basis of problem severity.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use administrative data to examine long-term patterns of outpatient psychotherapy utilization among a large heterogeneous sample of adolescents with varied behavioral health treatment needs. The findings reemphasize that most youths on Medicaid receive minimal outpatient psychotherapy services after their initial visit, despite psychotherapy being the gold standard of treatment for many behavioral health problems. In fact, <15% of the sample appeared to use psychotherapy consistently over time. This analysis serves as a necessary starting point to investigate both drivers and consequences of differences in psychotherapy utilization.

Despite some limitations, our findings do provide meaningful information. The classes identified point to the unique service needs of adolescents and the necessity to consider treatment across this developmental period rather than examining single, time-limited courses of manualized psychotherapy, which is typically presented in the literature. Additionally, although the observed variation in psychotherapy utilization patterns was unsurprising, this analysis quantifies the nature and extent of this variation over a long period. Furthermore, results from this large and diverse sample provide a benchmark for comparison in future studies considering long-term treatment trajectories. Such research may also be beneficial for policy makers and health care administrators to better understand the needs of the specific population they are serving and to allocate resources accordingly, particularly to high-risk groups of youths who may benefit most from continuous services.