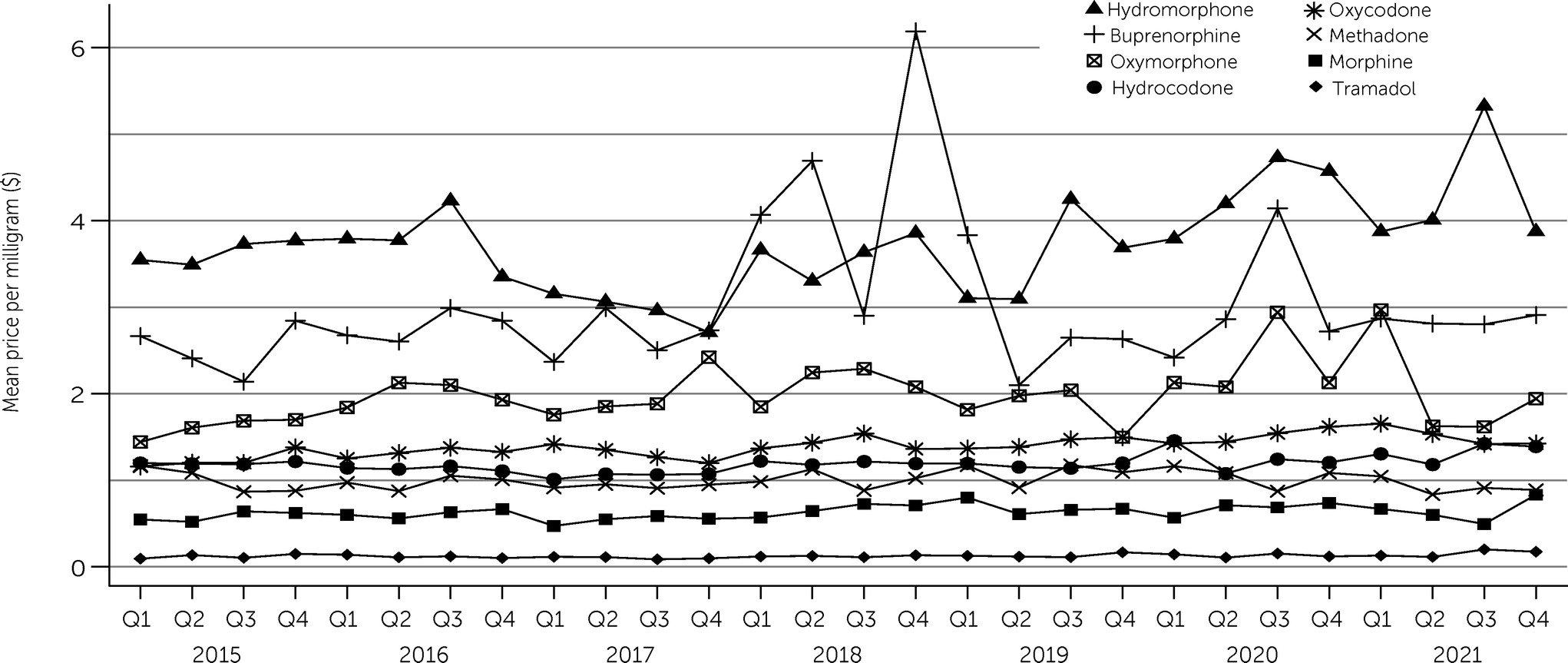

From March 2020 to May 2020, the number of prescriptions for opioid analgesics decreased because distribution to new patients was severely decreased (

6). Observed increases in street prices could reflect the decreased supply of analgesics and increased demand from illicit sources because some patients needing treatment for opioid use disorder were disconnected from treatment and other supports at a time when the stresses of the pandemic were possibly contributing to increased demand for opioids (

7). Higher street prices of prescription drugs could have caused an increase in substituting illicitly manufactured opioids, especially fentanyl, which can be produced cheaply because it is a synthetic opioid. The high potency of fentanyl also allows it to be transported in small quantities, which keeps its cost low (

8). Frequently dispensed opioids (e.g., morphine, oxycodone), which would be the most limited during the pandemic and create shortages, increased in price in 2020. Prices for these drugs then seemed to decrease by 2021 when dispensing potentially returned to previous patterns. Both high-potency opioid analgesics (oxycodone and hydromorphone) and low-potency opioids (morphine and hydrocodone) increased in street price per milligram. Although absolute differences in price per milligram appeared small, differences could be substantial for high-potency, extended-release opioids, such as 32-mg hydromorphone or 80-mg oxycodone, or if many pills are purchased at once. Disruptions to analgesic and postoperative medication availability may have contributed to increased nonmedical substance use, potentially directly through diverted drug use or indirectly through limiting patient access to needed care, causing patients to seek other options. Notably, changes in street prices per milligram for medications for opioid use disorder (buprenorphine and methadone) were not significant. Researchers had hypothesized that increased availability of take-home medications, as part of measures taken during the pandemic, would increase their availability and decrease their price (

6,

9). However, the importance of these medications to combat rising mortality may warrant further investigation into their ongoing diversion and price, particularly when evaluating nonpill forms of these drugs. One notable limitation of this study was that drug prices relied on self-reported data, and the prevalence of counterfeit products, possibly adulterated with other drugs such as fentanyl, can result in misclassification of sales to the incorrect drug or an incorrect attribution of the milligram strength of the drug in the RADARS System StreetRx Program. There was an increase in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids in 2020 (

1). Continued monitoring of street prices of prescription opioids may provide insight into future factors affecting the opioid crisis.