Despite this evidence, adoption of MBC is limited in practice (

5). A study from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) found that only 58% of VA providers reported collecting at least one measure for at least half of their patients, despite positive provider attitudes about MBC (

6). Community behavioral health care providers (BHCPs) use MBC even less. One national survey of 504 clinicians showed that only 14% reported using standardized progress measures at least monthly, and 62% never used them (

7). A survey of 314 psychiatrists revealed that more than 80% indicated that they did not routinely use scales to monitor outcomes when treating depression (

8). However, data are limited on MBC utilization among community BHCPs.

In this study, we analyzed data from a survey administered by Blue Cross–Blue Shield of North Carolina (BCBSNC), the largest health plan in the state, as part of an effort to improve the quality of behavioral health care. The survey asked BHCPs in North Carolina about their current use of MBC as well as their demographic and clinical practice characteristics. The survey also assessed multiple domains thought to affect use of MBC, which we call “barriers to use” (

9). The aims of the analysis were twofold: to estimate associations between provider and practice characteristics and MBC use and to quantify the relative importance of barriers to use. An assessment of the most common and influential barriers to adoption of MBC among community BHCPs will help payers, health systems, and providers develop implementation strategies to increase adoption of MBC and ultimately improve the overall quality of behavioral health services.

Methods

Survey Instrument

Two of the authors (B.C.K. and I.P.B.) developed a 30-item survey for BHCPs about provider and practice characteristics, self-reported use of MBC, and barriers to its use; they then fielded the survey during February and March 2021. Cognitive pretesting was conducted with five BHCPs to ensure that the survey items were interpreted as intended (

10).

Information on clinical and demographic characteristics was collected: sex included male, female, and nonbinary; race-ethnicity included White; Black; Latinx; Asian American, Pacific Islander, Native American, or other; and “prefer not to specify.” Providers could select multiple races and ethnicities. Although we acknowledge that race is a social construct, we expected that provider race-ethnicity may be correlated with unobserved caseload and regional factors. Questions also assessed clinical characteristics, including practice type, professional licensure, years of experience, treatment modalities provided, specialty training, and practice zip code.

MBC was defined in the survey as the systematic administration of symptom rating scales to assist the provider and patient in noting progress and to drive clinical decision making. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they used MBC with 0%, 1%–49%, 50%, 51%–99%, or 100% of their caseload. The survey contained a 16-question instrument designed to measure provider-level barriers to use of MBC (

9), and it was adjusted as needed after cognitive pretesting (a table showing theoretical barriers to the use of MBC and the associated survey questions is available in the

online supplement to this article) (

6,

9). Each of the 16 questions was designed a priori to assess one of five provider-level barriers: attitudes, knowledge and self-efficacy, lack of clarity on the clinical utility of MBC, administrative burden, and concern with data utilization (i.e., whether data will be used to judge providers’ clinical skills or to affect compensation) (

9). The barrier constructs also operationalize distinct aspects of a provider’s orientation toward MBC: attitudes represent an evaluative association held toward MBC, self-efficacy involves an assessment of one’s performance while using MBC, and concerns about data use are related to one’s clinical skills potentially being negatively assessed in comparison with injunctive social norms (

11–

13). Each question was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. Secondary analysis of the survey was granted an exemption by the institutional review board of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sample

The survey was e-mailed to the BCBSNC behavioral health Listserv of 5,255 providers as well as to leaders of local provider professional societies. Because recipients may have forwarded the survey and the number of recipients in each professional society was unknown, we were unable to calculate the response rate.

Coding and Imputing Responses

We used providers’ primary practice zip code, mapped to the 2013 U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Urban Influence Codes (

14), to explore the association between their practice Urban Influence Code and their responses. The 12 Urban Influence Codes were collapsed into three categories: large metropolitan areas (≥1 million), small metropolitan areas (<1 million residents), and nonmetropolitan areas (

14).

We excluded respondents who reported more than 70 hours per week of outpatient clinical care (N=5). We imputed missing values for the 16 questions regarding beliefs about MBC, including responses of “no experience/not applicable,” through multivariate normal multiple imputations, with practice and provider characteristics as predictors (

15). Values were binned into five Likert categories on the basis of absolute distance. We performed a sensitivity analysis by using listwise deletion of records with a missing value for any barrier index (N=30).

Barrier Index Construction

We developed barrier indices with the 16 questions described earlier. We examined correlation matrices between the responses to each of the 16 questions. The correlation pattern was largely consistent with the assignment of the 16 questions to the five barriers described in a previous review (

9). However, items regarding “attitudes” and “lack of clarity on the clinical utility” were highly correlated with each other and relatively uncorrelated with other items (

9). Therefore, we merged all questions designed to measure these two constructs into a single construct, described as “low perceived clinical utility.” The index for each of the four constructs was the average response to questions included in the given barrier construct, coding “strongly disagree” as 1 and “strongly agree” as 5 and reversing this coding as necessary. The indices had internal validity in item analysis (

16) and showed good reliability overall, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (see

online supplement) (

17). We calculated the means of the barrier indices to assess how strongly providers agreed, on average, with the component statements in the construct, deemed “endorsement” of the barrier. In the regression models, we standardized each barrier index to have a mean of 0 and an SD of 1 to facilitate comparison.

Data Analysis

In the first analysis, we used an ordered logit model to examine the relationship between practice and provider characteristics and frequency of MBC use. The predictor variables were sex, race-ethnicity, practice Urban Influence Code, years in the field, weekly hours of outpatient behavioral health care, whether the provider bills insurance, insurance distribution of the provider’s caseload, practice type (individual, small group [<10 providers], large group [≥10 providers], or facility based), licensure, specialty training, treatment modalities provided, and whether the provider’s training included instruction in MBC. Average marginal effects (AMEs) were calculated for each variable of interest, and they represent the percentage-point difference in the probability of use of MBC associated with a 10-unit increase (for continuous variables) or change of factor level (for categorical variables). We note values with p<0.10 in tables because of the relatively modest sample size for this model; for brevity, we focus our comments on those characteristics with the larger and statistically significant effects (p<0.05).

In the second analysis, we assessed the relative magnitude of association between the barrier indices and the use of MBC. We estimated an ordered logit model for each standardized barrier index, controlling for provider and practice characteristics. The resulting AMEs represent the percentage-point difference per SD increase of each barrier index. In a secondary analysis, we estimated a single-ordered logit model with all four barrier indices and the full set of provider and practice characteristics to explore whether the barriers mediated associations between these characteristics and use of MBC.

R, version 4.1.3, was used for initial data management (

18), and the R package ggplot2 was used for producing figures (

19). Stata, version 16.1, was used for all statistical procedures (

20). The Stata user-contributed module MIMRGNS was used to estimate AMEs after multiple imputation (

21).

Results

A total of 940 respondents completed the survey, with 922 eligible for inclusion. Respondents were excluded if they practiced outside North Carolina, reported weekly clinical care hours exceeding possible limits (e.g., 450 and 1,000 hours), indicated they were not health care providers or not practicing, or indicated they were responding to the survey for their agency in aggregate. Most identified as female (79%), White (72%), or master’s-level (80%) providers. Providers practiced in a variety of settings. Respondents practiced for a mean±SD of 25.1±10.7 hours per week.

Table 1 outlines additional provider characteristics.

A total of 224 providers (24%) reported never using MBC, 272 providers (30%) reported using MBC with 1%–49% of patients, 138 providers (15%) reported using MBC with 50% of patients, 171 providers (19%) reported using MBC with 51%–99% of patients, and 117 providers (13%) reported using MBC with all patients (see online supplement).

Multivariate analyses showed several factors associated with varying levels of MBC use, although few differences were found by race-ethnicity, sex, licensure type, or insurance billing (

Table 2). Providers trained in MBC reported greater use of MBC than those without MBC training (p<0.05). Longer time in practice (≥10 years) was associated with substantially lower frequency of MBC use (p<0.05), even after analyses controlled for MBC training. A practice located in a nonmetropolitan area was associated with a higher probability of providers’ use of MBC than was a practice located in a large metropolitan area (p<0.05). A large practice group was associated with an 11.0–percentage point reduction in no MBC use and with corresponding increases in the probability of using MBC with 50% and 51%–99% of patients (p<0.05), compared with non–large group practices.

Generalists were less likely to use MBC than nongeneralists (p<0.05), and substance use disorder specialists were more likely to use MBC (p<0.05). Providers who offered acceptance and commitment therapy were more likely to use MBC than those who did not offer this service (p<0.05). Providers who do not bill insurance reported lower use of MBC than those who do (p<0.05).

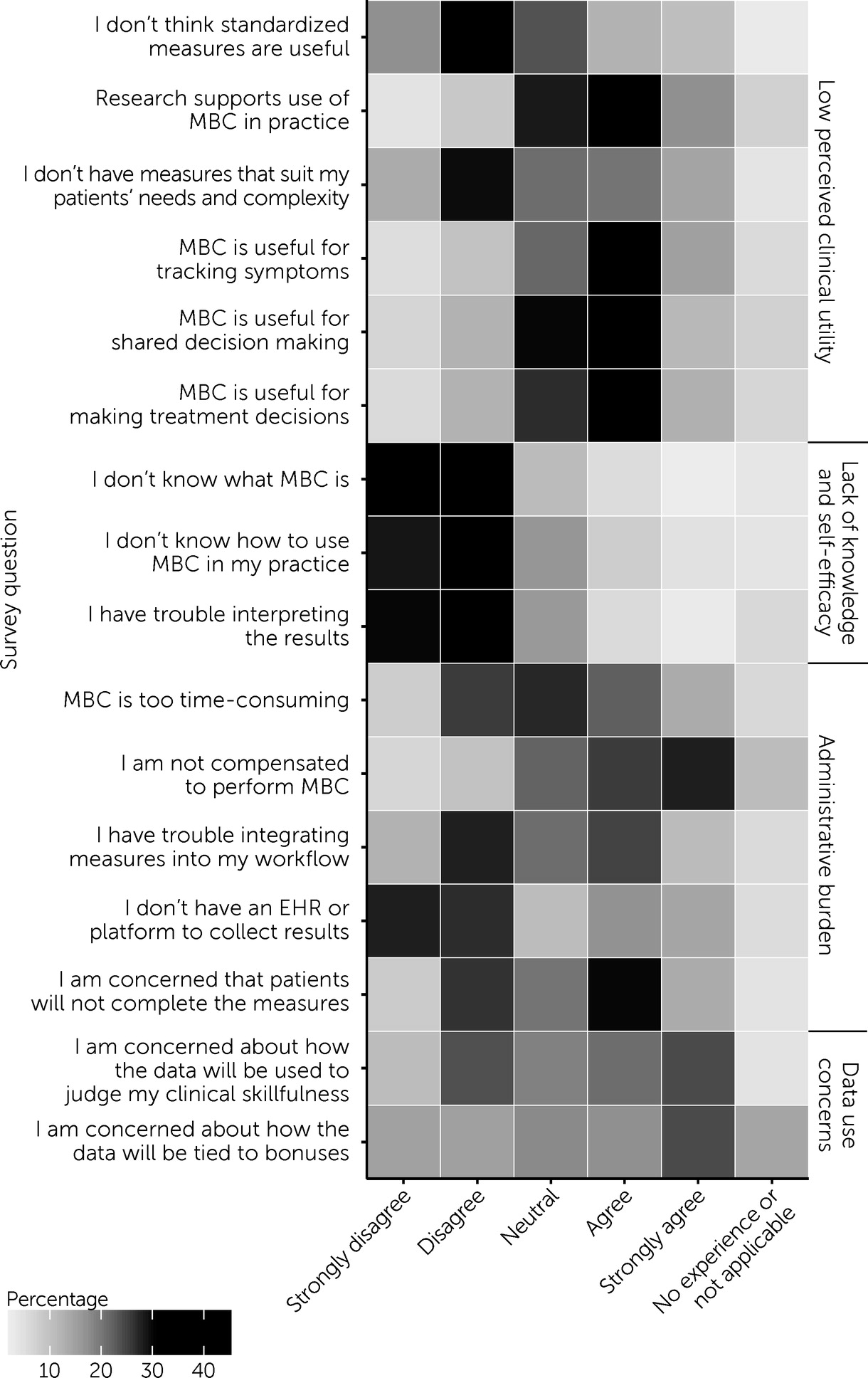

More than half of providers agreed or strongly agreed that research supports use of MBC in practice (54%, N=497), that MBC is useful for tracking symptoms (60%, N=553), that MBC is useful for making treatment decisions (50%, N=463), and that providers are not compensated for MBC (53%, N=489) (

Figure 1). Most providers strongly disagreed or disagreed with the following statements: “I don’t think standardized measures are useful” (53%, N=490), “I don’t know what MBC is” (80%, N=738), “I don’t know how to use MBC in my practice” (70%, N=641), “I have trouble interpreting the results” (72%, N=660), and “I do not have an EHR [electronic health record] or platform to collect the results” (55%, N=503). Together, these results suggest that most providers acknowledge the usefulness of MBC and disagree with several proposed barriers to MBC.

More than one-third of providers strongly disagreed or disagreed (42%, N=385) that current measures do not suit patients’ needs and complexity, whereas approximately one-third of providers strongly agreed or agreed (34%, N=316). Providers had a similar lack of consensus about MBC being too time-consuming (33% [N=300] strongly disagreed or disagreed vs. 35% [N=323] strongly agreed or agreed), trouble incorporating measures into their workflow (39% [N=361] strongly disagreed or disagreed vs. 35% [N=321] strongly agreed or agreed), and concern that patients will not complete measures (34% [N=310] strongly disagreed or disagreed vs. 43% [N=393] strongly agreed or agreed).

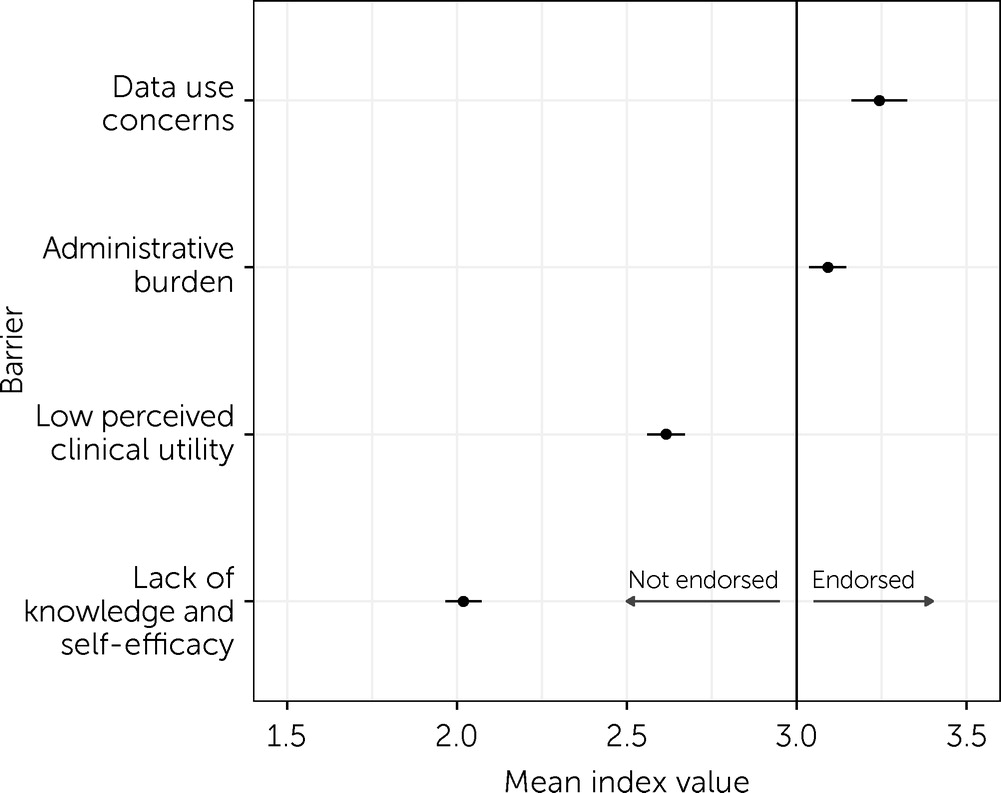

Data use concern was the most strongly endorsed barrier to MBC (mean index value=3.24, 95% CI=3.16–3.32, α=0.76) (

Figure 2; also see

online supplement), followed by administrative burden (mean index value=3.09, 95% CI=3.04–3.15, α=0.69), low perceived clinical utility (mean index value=2.62, 95% CI=2.56–2.67, α=0.87), and lack of knowledge and self-efficacy (mean index value=2.02, 95% CI=1.97–2.07, α=0.76). The indices were uncorrelated with each other (correlation coefficient=0.286–0.546), suggesting that they measure distinct barriers to MBC.

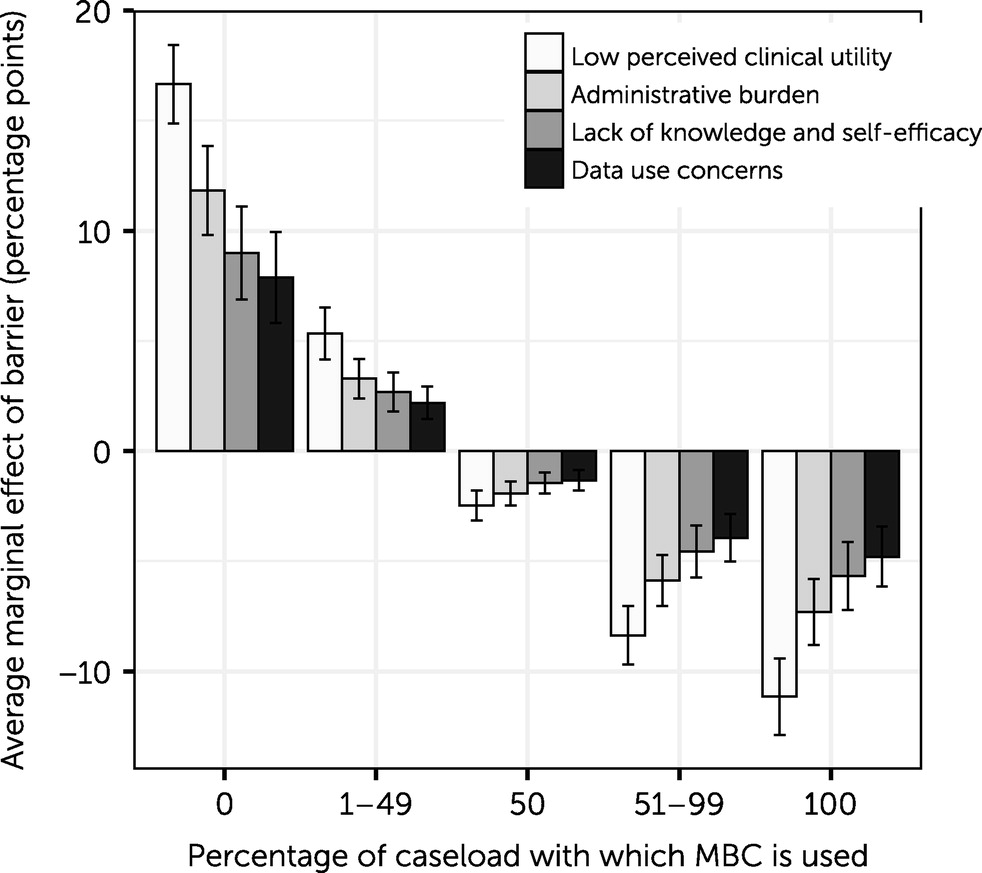

Analyses of the association between the barriers and use of MBC, adjusted for the full set of characteristics, showed that low perceived clinical utility was the barrier associated with the largest decrease in use of MBC: a 1-SD increase was associated with an increase of 16.7 percentage points in reported use of MBC with 0% of the caseload, followed by 5.3, −2.5, −8.4, and −11.2 percentage points for the other levels of utilization (p<0.05) (

Figure 3; also see

online supplement). This barrier was followed by (in order of magnitude) administrative burden, lack of knowledge and self-efficacy, and data use concerns. All four barriers were associated with statistically significant decreases in use of MBC (p<0.001). Listwise deletion instead of multiple imputation returned nearly identical results (see

online supplement), likely because of the relatively small number of missing values (N=30).

Finally, we found that including the barriers slightly mediated the association between provider and practice characteristics and use of MBC, with slight attenuation of most AMEs, although largely without changes in statistical significance (see online supplement). However, generalist training and substance use disorder training were no longer associated with a decrease and an increase in MBC use, respectively. In this model containing all four barrier constructs, data use concerns were no longer associated with changes in MBC use.

Discussion

This survey of BHCPs in North Carolina demonstrates that fewer than half of providers use MBC with at least half of their caseload. Our results also suggest that the most prevalent concerns about MBC may not be the most influential in determining its use. Concern about data use (that MBC may be used to judge providers’ clinical skills or affect their compensation) was the most strongly endorsed barrier yet the barrier least associated with real-world reported use of MBC; the barrier associated with the greatest decrease in MBC use was low perceived clinical utility. Together, these results suggest that providers are willing to practice MBC if they perceive it to be in the best interests of their patients, even if they have concerns about how data will be used.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate utilization of MBC among independent community BHCPs. We hypothesized that community-based providers would practice MBC less regularly than providers in VA settings because of the VA’s long history of collecting behavioral health outcome measures (

22). We found that whereas less than half (46%, N=426) of providers reported using MBC for at least half of their patients, providers’ reported use of MBC was greater than prior estimates of MBC use among community BHCPs (20%) (

5,

7,

8).

The variation in MBC utilization by provider type may indicate a need for flexibility and heterogeneity in incentives to expand use of MBC. Doctors of medicine and doctors of osteopathic medicine were less likely to use MBC frequently, consistent with prior research (

6). Providers trained in substance use disorders were more likely to use MBC, whereas those reporting generalist training were less likely to use MBC. Self-described generalists are a heterogeneous group, and their approach to patient care may be less amenable to systematic and objective assessment because MBC instruments focus on single conditions. A previous study showed that providers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) orientations held more positive attitudes toward MBC (

7). Contrary to our expectations, we did not find an association between CBT and use of MBC despite MBC being a core tenet of CBT (

23). Conversely, acceptance and commitment therapy, a more specialized form of therapy that also focuses on measurement, was associated with increased use of MBC.

Providers who had been in the behavioral health field for ≥10 years were less likely to frequently use MBC. It is possible that training on the use of MBC has recently become a standard practice, although providers who have been practicing for a longer time may feel an increased sense of competence and less desire to use manualized interventions and systematic measurement.

Several of the provider and practice characteristics associated with the use of MBC are nonmodifiable, but policy makers and payers should still consider that incentivizing use of MBC may lead to varied results in these distinct groups. Large group practices had higher levels of MBC use possibly because of more robust infrastructure, including EHRs and administrative staff, which may facilitate MBC uptake (

24). Surprisingly, providers in nonmetropolitan areas demonstrated more frequent use of MBC, even after adjusting for covariates.

Training in MBC is a modifiable factor that is positively associated with MBC use; however, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow us to infer that training has a causal effect on MBC use. Providers who are already aligned with MBC principles may be more likely to seek training in its use. We did not have information on voluntary versus mandatory training.

The most strongly endorsed barrier, concerns about data use, was associated with the smallest decrease in use of MBC. This finding suggests that although providers express concerns about how MBC data will be used, these concerns do not correlate with a decrease in use of MBC.

Administrative burden was associated with a decrease in MBC use. Heavy caseloads and time restrictions limit use of evidence-based practices (

25). However, MBC may streamline treatment (

1). Advances in technology may decrease administrative burden by allowing patients to complete assessments in the waiting room (

26). Measurement feedback systems, or health information technologies that support MBC implementation, have demonstrated that they lead to increases in MBC use (

27).

This study showed that the barrier associated with the greatest decrease in MBC use was low perceived clinical utility, which is consistent with previous research (

8,

28). Our study produces new estimates of the relative importance of this barrier for a sample of mostly master’s-trained clinicians in the community setting. Of note, providers generally did not feel that they lacked knowledge about MBC. Initiatives that only aim to address knowledge gaps may have less success than those attempting to understand and address providers’ concerns about the clinical utility of MBC.

Limitations of this study include low participation by doctors of medicine and doctors of osteopathic medicine (N=32) as well as by advanced practice providers (N=20). In addition, the data are from a single state, and regional variation in MBC adoption may exist. The survey response rate could not be determined because of our snowball sampling method; thus, we were not able to determine differences between respondents and nonrespondents. It is likely that selection bias favored providers who have stronger opinions about MBC and were willing to respond to a survey from an insurance company. Last, because this study had a cross-sectional design, it is impossible to infer causality.