The COVID-19 pandemic and related stressors (e.g., lockdowns, uncertainty, social isolation, and socioeconomic insecurity) have led to a variety of poor mental health outcomes, including elevated incidence and exacerbation of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (

1,

2). Furthermore, growing evidence indicates that critical disparities place many marginalized people and communities at elevated risk for poor mental health outcomes linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (

3,

4). For example, pandemic control policies in the United States have been associated with poor mental health outcomes among women, particularly women experiencing various forms of socioeconomic and related insecurity, as well as women and men with preexisting psychiatric disorders (

2,

5,

6). Racial and ethnic minority populations, as well as other marginalized populations, may face additional preexisting and systemic stressors (e.g., socioeconomic insecurity, racism, social isolation, limited access to health and mental health services, chronic stress, and past trauma) thought to contribute to poor mental health and stress-related outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (

3,

4,

6). Building on emerging research into social inequities and related health disparities among marginalized populations during the pandemic, in this study we focused on mental health among the large and fast-growing, yet understudied, populations of forcibly displaced persons (FDPs) seeking sanctuary.

Forced Displacement During the COVID-19 Pandemic

For the >82 million FDPs worldwide (

7), the stressors and sequelae of the pandemic may be magnified significantly (

4,

8–

10). Before the pandemic, risk for poor mental health among FDPs was linked to pre- and peri-migration trauma and stress as well as postmigration living difficulties (

11,

12) characteristic of high-risk postdisplacement settings (e.g., resettlement communities) (

13–

15). Such postmigration difficulties include insecure residential status; food, housing, and income insecurity; limited access to social, general, and mental health services; social isolation; and other chronic stressors (

11,

12). The COVID-19 pandemic has been theorized to exacerbate these preexisting chronic stressors and inequalities among FDPs (

16) and thereby result in poor mental health outcomes (

16–

18).

Empirical studies of FDPs’ mental health during the pandemic are now emerging. Several studies, conducted in various populations and postdisplacement settings, have documented that the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19–related socioeconomic factors, and the pandemic as a reminder of past traumatic life events were associated with poor mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and stress among refugees (

19–

21). In the largest study of its kind to date, the World Health Organization carried out a large online screening survey (ApartTogether) among migrants (N=28,853) in approximately 170 countries over the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic (April–October 2020). A large majority of respondents were from high-income countries, had higher education, lived in secure accommodations, and had secure residency status. The survey was used to measure several pandemic-related experiences and stressors, including perceived worsening of mental health outcomes related to the pandemic through single-item screening questions (e.g., “feeling anxious” and “feeling depressed”). The most elevated rates of perceived worsening of mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic were observed among migrants living in refugee camps, asylum centers, or on the streets and in insecure accommodations (

22). A follow-up analysis among a subsample of survey respondents (N=20,742) documented that women, as well as men and women struggling with basic needs, reported particularly elevated rates of worsening of mental health due to the pandemic (

23).

Building on this work, research is now needed regarding unrecognized asylum seekers and other FDPs living in fast-growing and unstable postdisplacement settings, wherein risk for poor mental health and its exacerbation during the pandemic may be most prevalent and severe (

10,

15,

23). Specifically, studies and data are needed to help specify the stress- and trauma-related mental health outcomes (i.e., posttraumatic stress [PTS], depression, anxiety, and suicidality) exacerbated by the pandemic among FDPs. To do so, it is important to measure mental health outcomes with psychometrically reliable and valid measures. Likewise, studies are needed regarding malleable risk factors (e.g., sociocontextual factors) linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (

17) that may be readily targeted by policy-level interventions (

18,

22).

Discussion

We aimed to test the association between the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically, socioeconomic insecurity related to the pandemic, and stress- and trauma-related mental health outcomes among East African asylum seekers living in an unstable postmigration setting in Israel. First, during national lockdowns due to COVID-19 control policies, asylum seekers reported higher levels of anxiety and, among women, an elevated rate of suicidal ideation, relative to a sample of asylum seekers from the same community in the months before the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, no pre–post pandemic differences were observed for depression or PTS. These null effects, however, may be related to very high levels of symptomatology in the pre–COVID-19 participants who had been exposed to high levels of traumatic stress and postmigration living difficulties before the pandemic (

26,

41–

43). Notably, the two samples did not differ significantly in terms of demographic characteristics, trauma exposure history, or postmigration living difficulties. Accordingly, we are reasonably confident that differences, or the lack thereof, between the samples may be ascribed to effects associated with the pandemic.

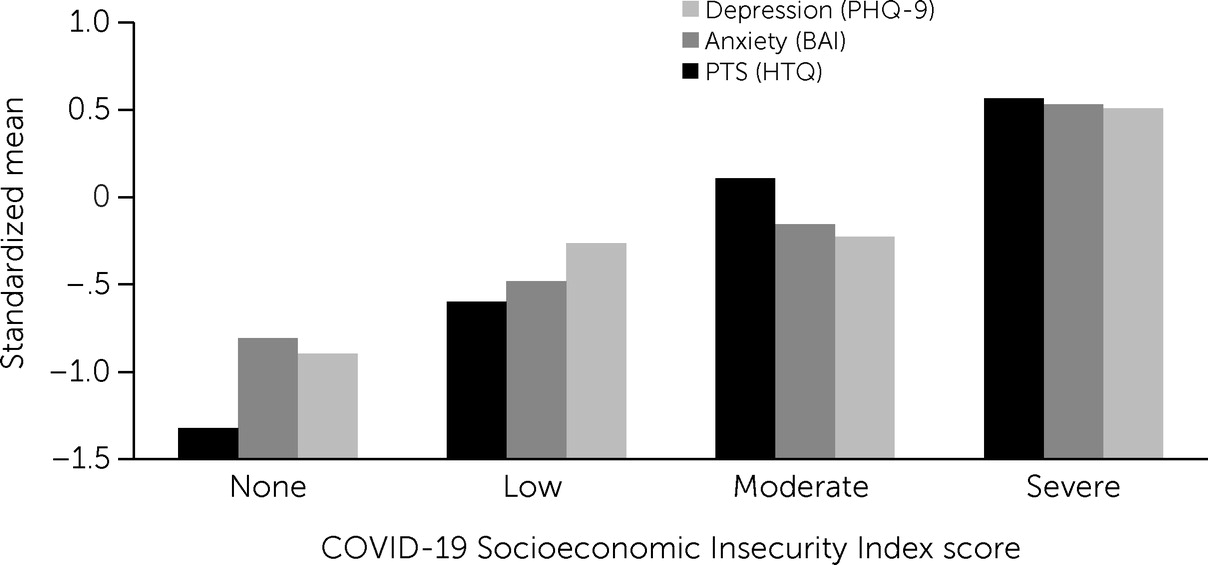

Second, as predicted, the association between insecurities related to the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health outcomes among asylum seekers was strong and statistically significant. The greater the degrees of pandemic-related food, housing, and income insecurities, the greater the severities of anxiety, depression, and PTS symptoms and higher the rates of probable depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation. For example, among asylum seekers experiencing food, housing, and income insecurities due to the pandemic, 58% (N=14 of 24) of the subsample reported current suicidal ideation, and 71% (N=17 of 24) reported probable depression. These rates were almost twice those observed among the pre–COVID-19 participants, who also had high levels of traumatization and chronic stress (31% [N=49 of 158] reported suicidal ideation, and 36% [N=57 of 158] reported depression); moreover, these rates were approximately six times higher for suicidal ideation and 10 times higher for depression than the rates observed in other nonclinical populations before the COVID-19 pandemic (

26,

44,

45).

This study’s findings are important observations regarding the potential association between COVID-19–related socioeconomic insecurity and mental health outcomes among FDPs in this type of unstable postdisplacement context. Indeed, because anxiety was elevated in the COVID-19 sample, compared with the pre–COVID-19 sample, these findings are partially consistent with theory and recent findings in other marginalized populations for whom preexisting health disparities and inequities may be significantly exacerbated by COVID-19 control policies (

3,

4,

20,

21). Our findings are also aligned with previous research documenting that marginalization, tied to unrecognized asylum status in high-risk postdisplacement settings, contributes to poor mental health outcomes (

3,

10,

18,

46,

47). Furthermore, our findings are mostly consistent with and extend recent findings from the World Health Organization’s ApartTogether survey. Migrants with insecure residential status and limited access to basic needs due to COVID-19 reported the highest rates of perceived mental health concerns during the pandemic (

22,

23). We also note that our findings highlight the potential mental health significance of intersectional marginalization for FDPs within the pandemic (

48). Indeed, of particular urgency and global public health concern, we observed an elevated risk for suicidal ideation among female asylum seekers (

23,

48,

49). Thus, COVID-19 and pandemic control policies, when paired with preexisting social marginalization and migration policies that do not provide a safety net postdisplacement (

50), are likely to exacerbate stress- and trauma-related mental health outcomes among asylum seekers.

In light of the growing evidence base, this study’s findings may have tentative implications for postdisplacement policy making, social justice advocacy, humanitarian aid, and clinical science and practice. First, awareness among policy makers and promotion of public policy–based interventions oriented to guarantee basic human rights and socioeconomic security (

51,

52) may be crucial to mitigating negative mental health outcomes among FDPs during the COVID-19 pandemic (

53,

54). Policy relevant to residential status may be particularly important and effective because temporary status has been linked to poor socioeconomic integration postdisplacement (

55). Second, humanitarian aid organizations and NGOs that provide services to ensure food, housing, and income security for FDPs during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis may be well suited to assess the incidence of poor mental health outcomes and deterioration and, specifically, guide efforts aimed at suicide prevention (

56–

58). Likewise, governmental organizations and NGOs facilitating food, housing, and income security may be an important part of social justice advocacy and public health care for FDPs (

22,

52). Finally, to complement policies and services supporting socioeconomic security during the pandemic, clinicians working with FDPs can also aim to help prevent and mitigate the impact of COVID-19–related socioeconomic insecurity on mental health outcomes with intervention programs such as Self-Help Plus (

51), Group Problem Management Plus (

59), or Mindfulness-Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees or its mobile adaptation (

26).

Although our findings may inform the collective understanding of the magnitude of the emerging pandemic-related mental health crisis among FDPs, this study was limited in several ways, which should be addressed in future research. First, the COVID-19 sample was small, consisting of 66 asylum seekers. The sample size was restricted by the acute period during the COVID-19 crisis, restrictive pandemic control policies, and a required in-person assessment with a cultural mediator and translator. We have found that despite these logistic constraints, our assessment methodology yielded significantly more reliable and valid reporting than online assessments completed autonomously by asylum seekers in such highly unstable postdisplacement conditions. Thus, on balance, we believe that the sample size versus data collection integrity trade-off was necessary. Second, this study did not have a repeated-measures design. Although the pre- and postpandemic samples were closely matched on key demographic characteristics, trauma history, and postmigration living difficulties, inference about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes must be interpreted cautiously. Although recruitment was from the studied community, larger-scale population data on unrecognized East African asylum seekers residing in this region of the Middle East are very limited. We therefore could not definitively evaluate to what degree the samples represented the population from which they were selected. It is therefore important for researchers in future studies to test whether these findings are relevant for other FDP populations and postdisplacement settings. Last, in this study, we relied on a self-reported measure to assess COVID-19–related socioeconomic insecurity. In future studies, researchers could also incorporate objective indices of these outcomes, although doing so may be more feasible in stable postmigration resettlement settings than in the present high-risk urban context in which such objective data are not likely to be available.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the asylum seekers who participated in the two studies, before and during a COVID-19 lockdown. For the pre–COVID-19 study, the authors thank Sendel Abraham, Dawit Weldehawariat Habtai, and Mogus Kidane for their assistance in translation and data collection; the team at the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Kuchinate for hosting the study, including Dr. Diddy Mymin-Kahn, Sister Azezet Habtezghi Kidane, Ruth Garon, Hewan Desta, Eden Gebre, Asmeret Haray, Fiori Yonas, and Achbaret Abraha; and Ron Peleg for his help in participant recruitment and data collection. For the COVID-19 study, the authors thank Yotam Phung, Michael Tesfahanes Afworki, and Alexandra Rzyanina for their help in data collection; the authors also thank the team at the NGO Assaf for collaborating and hosting the mobile lab to carry out the study, including Tali Ehrenthal, Sari Urim, Yael Federman, Miriam Meyer, and Michal Shechter. Finally, the authors thank Meital Gil Davis for coordination of logistics, research funding, and personnel for both studies; Ido Lurie, M.D., for pro re nata psychiatric consultation; and Yikealo Beyene for expert translation of study materials.