Weighted lifetime prevalence of probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among U.S. veterans is about 8.0% (

1), and era-specific estimates range from 18.7% to 37.3% (

2–

4). Veterans with PTSD within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have increased dramatically, with nearly 400,000 having received a PTSD diagnosis during the 2002–2015 period (

5). In 2010, the overall prevalence of PTSD in VA primary care was 11.5% (

6). PTSD has been associated with comorbid mental health conditions, decreased functioning and quality of life, unemployment, greater health care costs, and difficulty reintegrating into civilian society (

2,

7–

11).

Although antidepressant therapies may improve PTSD symptoms (

12), response rates are typically ≤60%, with remission rates of ≤30% (

13). Complementary to neurobiological targets, advances in nonpharmacological interventions for PTSD have progressed (

14,

15). Currently, trauma-focused cognitive or behavioral psychotherapies are the first-line, evidence-based interventions recommended by the PTSD practice guidelines of the VA and U.S. Department of Defense (

12). However, up to two-thirds of military personnel and veterans continue to have PTSD symptoms after trauma-focused psychotherapy (

16). Treatments are not effective for every individual, and remission rates are low (

17,

18), making PTSD a chronic and debilitating condition. New treatments that improve functioning and quality of life, implemented together with existing treatments, would be valuable.

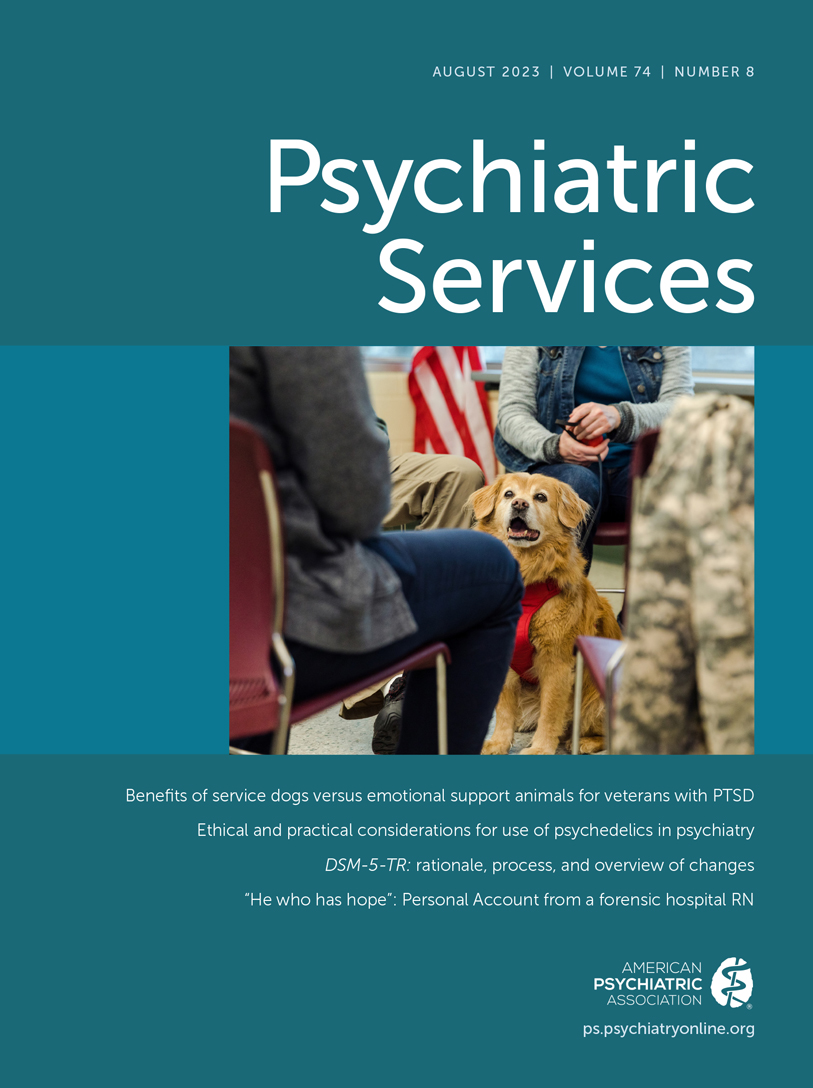

Multiple studies have reported physiological components to human-dog attachments. Dogs have been shown to have beneficial effects on the mental health, quality of life, and well-being of wounded warriors (

19,

20), nursing home residents (

21,

22), and institutionalized people (

23). The human-animal bond can be particularly strong for individuals who are psychologically vulnerable (

24). Veterans with a mental health service dog trained to mitigate PTSD symptoms have shown improvements in symptoms, quality of life, and social functioning (

25). Therefore, utilization of service dogs trained specifically to assist veterans with PTSD has been considered a promising augmentation strategy, in part because individuals with high anxiety sensitivity and behavioral avoidance tend to decline exposure-based psychotherapies but may be more accepting of a service dog, which may make individuals with PTSD amenable to modular or combination treatments (

16).

Guide, hearing, medical alert, and mobility dogs are examples of service dogs trained to perform tasks directly related to a person’s disability. Service dogs for PTSD are taught a variety of tasks specific to assisting individuals with PTSD, such as turning on lights in a dark room, sweeping the perimeter of a room, retrieving an object, or providing space between the individual and a person approaching. Service dogs are entitled to accompany their disabled handler into public buildings (

26). Pet dogs or emotional support dogs have no special training; their sole function is to provide comfort, which does not qualify them to legally access public buildings under the Americans With Disabilities Act (

26). To determine whether the benefits from a service dog extend beyond the general benefits of the human-dog bond, we compared outcomes after the provision of a service dog versus an emotional support dog.

In this trial, we assessed whether providing a service dog versus an emotional support dog to veterans diagnosed as having PTSD improved overall functioning and quality of life over time. Additionally, we assessed PTSD symptoms, suicidal behavior and ideation, depression, sleep quality, anger, and economic outcomes (

27–

29).

Methods

We conducted a randomized, two-arm, parallel-design, multicenter clinical trial recruiting veterans diagnosed as having PTSD from three VA medical centers. The study’s rationale and design have been published (

30). The trial was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) with an executive committee responsible for trial oversight (see the

online supplement to this article for inclusion and exclusion criteria). The economic analysis was approved by the Stanford University IRB.

Veterans were randomly assigned to receive either a service dog or emotional support dog. Service dogs were required to pass the American Kennel Club Canine Good Citizen (

31) and Assistance Dogs International Public Access (

32) tests and were taught to perform five tasks specific to a handler’s PTSD (

30): “lights” (locate and turn on a light in a dark room), “sweep” (enter a room and sweep the perimeter), “bring” (retrieve an object at the handler’s request), “block” (stand in front of the handler to provide space between the participant and the person approaching), and “behind” (stand behind the handler to provide space between the participant and a person approaching from behind). Emotional support dogs were required to pass the American Kennel Club’s Canine Good Citizen and Community Canine tests and were expected to be well behaved and well socialized but were not taught the five PTSD-specific tasks.

Assignment and Follow-Up

Each eligible participant was randomly assigned to either a service dog or an emotional support dog. A block randomization scheme was used to randomly assign participants by center and dog vendor to the two treatment groups. After the random assignment and before pairing (i.e., when the participant received the study dog), a participant observation period (with a minimum length of 3 months) began, during which the study team and participants remained blind to assigned treatment condition. During the observation period, participants were required to complete a dog care course that included information on the general care and feeding of dogs, dog health issues and when to seek medical attention, recognition and prevention of dog aggression, financial burden associated with having a dog both during and after the study, the differences between service dogs and emotional support dogs, and the legal rights of the owners of each. During this time, participants were also interviewed so that a dog could be selected that would match the participant’s physical traits and lifestyle. Following this observation period, participants then received (i.e., were then paired with) either a service dog or an emotional support dog on the basis of their previous random assignment and were actively followed up for 18 months. Participants were assessed for primary and secondary outcome measures along with the collection of postpairing dog-related information via study questionnaires at screening, baseline, and after the observation period but before pairing (clearing), as well as at weeks 1 and 2 postpairing, months 1 and 2 postpairing, month 3 postpairing, and every 3 months through month 18 postpairing (see the online supplement for the visit schedule). Assessments took place during in-clinic visits, home visits, and telephone calls.

Therapeutic Outcomes

Primary outcomes were health and activity limitations (i.e., disability, assessed via the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale II [WHODAS 2.0]) and health-related quality of life (assessed via the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey [VR-12]). For the WHODAS 2.0, total scores range from 0 (no disability) to 100 (full disability) (

33). Two subscores were derived from the VR-12: a physical component score (PCS), assessing general medical health, physical functioning, physical role limitations, and bodily pain, and a mental component score (MCS), assessing emotional, vitality and mental health, and social functioning (

34,

35). For this study, the survey question regarding problems with work or other daily activities because of any emotional problems (question 4b) was modified to mirror that of problems with work or other daily activities because of any physical problems (question 3b). Higher PCS and MCS scores indicate better quality of life.

Secondary outcomes included sleep quality (assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]) (

36), suicidal behavior and ideation (assessed with the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale [C-SSRS]) (

37), changes in PTSD symptoms (assessed with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 [PCL-5]) (

38), and depression severity (assessed via the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]) (

39). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) (

40) was administered to assess the essential features of PTSD, and the seven-item Dimensions of Anger Reactions (DAR) scale (

41) was used to assess anger disposition directed toward others. Outcome measures were continuous (except suicidal behavior and ideation, assessed as a binary variable) and were assessed at baseline, clearing, and 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months postpairing.

Economic and Medication Adherence Outcomes

Economic outcomes data were obtained through participant self-report and VA administrative data. Self-reported data included non-VA health care and non-VA medication use, as well as work productivity and employment, measured via the six-item Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health Problem, version 2.0 (WPAI) (

42). VA administrative data were used to identify inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy utilization and costs by using data from Managerial Cost Accounting inpatient treating specialty and outpatient files (

43). Medication information was extracted from the Managerial Cost Accounting pharmacy file. Cost and utilization data were grouped into mutually exclusive categories of care by using inpatient treating specialty or outpatient clinic stop codes: inpatient medical/surgical, inpatient psychiatry/mental health, inpatient substance use treatment, inpatient other, outpatient medical/surgical, outpatient pharmacy, outpatient psychiatry/mental health, outpatient substance use treatment, and outpatient other. VA cost and utilization data for 18 months, starting on the participant’s pairing date, were summarized into six 90-day periods. Costs were adjusted to 2018 prices with the annual Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers. Non-VA health care utilization was converted to costs on the basis of average 2019 VA data (i.e., $18,882 per inpatient stay, $283 per outpatient visit, and $392 per emergency visit).

Proportion of days covered (PDC) was used to measure medication adherence for common psychiatric medications (VA drug class codes: CN600–699, antidepressants; CN700–799, antipsychotic medications; CN302, benzodiazepines; and CN300, CN301, and CN309, other hypnotics and sedatives). PDC was computed by drug class if at least one refill was in the drug class (i.e., secondary adherence) (

44–

46). PDC was also measured for the 18 months before pairing.

Statistical Analysis

To calculate sample size, data from two VA Cooperative Studies Program studies were first used to estimate mean±SD WHODAS 2.0 scores. Data from a study on a mindfulness-based stress reduction program (

47) were used to estimate mean±SD scores on the VR-12 PCS and MCS. The minimal clinically important difference was set at a 10-point difference between groups in WHODAS 2.0 total score and at a 15% difference between groups for the VR-12 PCS and MCS scores (

30). For a statistical significance of p=0.05 and a power of 85%, 110 participants paired per group were required to account for a maximum of 25% postpairing participant loss or dropout rate. Analyses were based on the per-protocol population, defined as the participants paired with a service or emotional support dog, and included data collected after any replacement dogs were provided. Consequently, the per-protocol population may be considered a modified intent-to-treat population, because it comprised a subset of the participants undergoing random assignment (the intent-to-treat population) and maintained the randomization structure but excluded individuals in a justified way (e.g., never starting treatment or never paired with a dog). Participants in the per-protocol population were followed up after pairing, regardless of whether the study dog remained or was removed or replaced. Another data set was derived from the per-protocol population by removing any data collected after a replacement dog was provided (per-protocol [replacement dog] data removed [PPDR]).

For all therapeutic outcomes, except suicidal behavior and ideation, we used a linear mixed repeated-measures model to determine changes over time between the service dog and emotional support dog groups, with gender, center, and baseline score on the measure included as prespecified covariates, as well as a time-by-treatment interaction (with time as a categorical variable). Suicidal behavior and ideation were examined with a generalized linear mixed model. All models were analyzed with the per-protocol population and rerun with the PPDR population to examine sensitivity of the results to dog replacements. Additional analyses using a linear mixed repeated-measures model with random intercepts were conducted. The random intercept was based on the participant and was used to correct standard errors given the repeated observations for each participant. Linear contrasts tests for a difference between groups across time (to address the study hypotheses) and at 18 months (post hoc analyses) were conducted with effect coding.

Panel models were analyzed with a person random effect to examine whether treatment assignment was associated with VA health care utilization and costs, with analyses controlled for follow-up time. Models included dummy variables for periods after pairing, gender, and center. In separate models, interactions of treatment and follow-up periods were used to identify time-varying effects. For cost data, a linear model fit the distribution best, per the modified Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic (

48). For utilization data, negative binomial regression was used (except that Poisson regression was used for outpatient pharmacy utilization). PDC was estimated with a linear model, with analyses controlled for baseline PDC (

49). For the work productivity analysis, we capped reported hours worked at 50, but in a sensitivity analysis, we used actual reported hours worked. All statistical tests were two-sided, with a 5% significance level, and were performed with SAS, version 9.2/9.4, and with Stata, version 16.

Results

From December 2014 through June 2017, informed consent was provided by 287 participants, with 227 meeting the eligibility criteria. Of these veterans, 114 (50%) were randomly assigned to receive a service dog and 113 (50%) were randomly assigned to receive an emotional support dog (see the online supplement for a flow diagram). Forty-six (20%) participants were excluded from the study before pairing with a dog. The remaining participants (N=181) were paired with a dog—of these, 97 (54%) received a service dog, and 84 (46%) received an emotional support dog—after a median observation period of 5.2 months (range 3.0–12.9). Nine participants—three (3%) with a service dog and six (7%) with an emotional support dog—received a replacement dog at some point after pairing. Among the paired participants, nine (9%) service dog and 19 (23%) emotional support dog participants discontinued the intervention before completing 18 months of follow-up.

Participant Characteristics

Participants paired with a dog had a mean±SD age of 50.6±13.6 years (range 22–79), and most were male (80%), White (66%), and non-Hispanic (91%); 38% were married, 36% were divorced, and 13% had never married (

Table 1). Most of the participants had served in the army (53%) and in a combat area (74%). Just over one-third (38%) of the participants used alternative therapies, such as yoga (8%, N=15), acupuncture (5%, N=9), massage (4%, N=8), and meditation (21%, N=38), to help with PTSD symptoms. General medical and mental health disabilities were observed among 33% and 43% of participants, respectively, and 28% worked part- or full-time. The two groups appeared to be balanced in all characteristics except for a difference in part-time volunteer status. Additionally, results on outcome measures at baseline were balanced between the two groups. According to results from the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, version 7.0.0, current major depressive disorder was most prevalent (37%, N=66), with current panic disorder observed for 13% (N=23) of participants, current generalized anxiety disorder for 7% (N=13), alcohol use disorder for 4% (N=8), and substance use disorder for 1% (N=1) (see the

online supplement). No group differences in these disorders were found.

Primary Outcomes

For both groups, WHODAS 2.0 scores decreased at 18 months (indicating less disability) from those at 3 months. After adjustment for baseline score, center, and gender, the linear mixed repeated-measures model showed no treatment group difference, although a trend toward a significant difference was observed (p=0.052;

Table 2). The model showed a time effect, indicating scores changed over time, but no significant interaction between time and group (see the

online supplement). Additional contrast testing for a difference between groups at 18 months indicated no significant difference (

Table 2).

Adjusted models indicated no significant group differences or change over time in the VR-12 PCS score, but some improvement (i.e., increase) in the VR-12 MCS score over time was observed in both groups. VR-12 MCS scores were 31.1 at baseline and 39.0 at 18 months for the emotional support dog group and were 30.7 at baseline and 40.3 at 18 months for the service dog group. In the adjusted models (see the

online supplement), no significant group difference or time effect was observed for the VR-12 PCS score. For the VR-12 MCS score, the model indicated a within-participant time effect after pairing, but no treatment difference between the two groups. Model contrasts confirmed no differences between the two groups for the VR-12 PCS and MCS scores over time and at 18 months (

Table 2).

Least-squares means (from adjusted models) over time further supported the results of the WHODAS 2.0 analysis, showing minimal separation between the groups, and of the VR-12 scores, confirming the absence of significant effects of treatment allocation. Similar findings were observed for the PPDR population and random intercept models (see the online supplement).

Importantly, although this study had multiple primary outcomes, no adjustment of the probability level in statistical analyses was considered during the planning and design of the trial. We took this lack of an adjustment into consideration when interpreting the results, but because no differences were observed between the two groups over time for the primary outcomes, an adjustment for multiple comparisons would not have affected the trial results.

Secondary Therapeutic Outcomes

We observed a consistent separation in PSQI scores between the two groups over time and a decline in scores (indicating improved sleep quality) over time in both groups. Scores were 14.3 at baseline and 12.5 at 18 months for the emotional support dog group and 13.6 at baseline and 11.7 at 18 months for the service dog group (see the

online supplement). The adjusted model showed no group difference but did indicate a time effect, with improvement in PSQI score over time (see the

online supplement). Contrast testing further supported the absence of group differences in PSQI score over time and at 18 months (

Table 2).

Levels of suicidal behavior and ideation did not appear to vary between the two groups until months 15 and 18, when some separation started to appear. The rate of suicidal behavior and ideation was 16% at baseline and 28% at 18 months for the emotional support dog group and was 25% at baseline and 15% at 18 months for the service dog group (see the

online supplement). The adjusted model indicated a time effect but no treatment or time-by-treatment effect, indicating changes in suicidal behavior and ideation over time but without a significant difference between the groups over time (see the

online supplement). Contrast testing indicated no difference between the two groups across time but did disclose a difference between the groups at 18 months (

Table 2), consistent with the separation seen between the groups after 12 months (see the

online supplement). Least-squares means determined with the adjusted model indicated a suicidal behavior and ideation rate of 30% for the emotional support dog group versus only 14% for the service dog group at 18 months, suggesting a potential reduction in suicidal behavior and ideation with longer pairing for the service dog group versus the emotional support dog group.

A decline in PCL-5 scores (indicating improvement in PTSD symptoms) was seen in both groups. Scores were 47.0 at baseline and 35.2 at 18 months for the emotional support dog group and 48.3 at baseline and 31.7 at 18 months for the service dog group (see the

online supplement). Some separation in scores between the groups started to appear at 9 months, with scores for the service dog group decreasing more than those for the emotional support dog group. The adjusted model indicated a significant group difference, time effect, and interaction (see the

online supplement). Individuals in both groups experienced improvement in PTSD symptoms (i.e., lower PCL-5 scores) over time but in different ways. Participants with a service dog had a continued decrease in PTSD symptoms over time, whereas those with an emotional support dog had stabilized PCL-5 scores from 6 to 15 months and then decreased scores at 18 months. Model contrasts further indicated a group difference over time and at 18 months (

Table 2). The model showed an approximately 3.7-point improvement in PCL-5 score over time for the service dog group versus the emotional support dog group (p=0.036).

In both groups, PHQ-9 scores declined (indicating improvement in depression) through 6 months postpairing (see the online supplement). Scores for the emotional support dog group increased at 9 months, then stabilized until scores began to decrease again at month 18. Scores for the service dog group steadily declined through 9 months, at which time the scores stabilized until they decreased again at 18 months. Scores were 13.1 at baseline and 9.4 at 18 months for the emotional support dog group, and 12.8 at baseline and 8.2 at 18 months for the service dog group. The adjusted model indicated a time effect, with a reduction in depression (i.e., lower scores) observed over time. Despite some observed separation in scores between the two groups after 6 months, this difference was not statistically significant in the models (see the online supplement).

DAR scale scores declined among individuals in both groups, with some separation between the two groups starting after 6 months postpairing, when scores for the service dog group continued to decline (indicating improvement in anger reactions), unlike those for the emotional support dog group. Scores were 23.8 at baseline and 20.2 at 18 months for the emotional support dog group and 21.8 at baseline and 15.9 at 18 months for the service dog group. The adjusted model indicated a time effect, with both groups experiencing less anger reactivity over time. After 6 months, participants in the service dog group continued to have fewer anger reactions, whereas those in the emotional support dog group experienced an increase at 9 months and then a decrease (see the online supplement). However, no statistically significant differences between the groups were observed.

Economic Outcomes

Receipt of a service dog compared with receipt of an emotional support dog did not significantly affect VA costs for any category of care (

Table 3) nor VA health care utilization, except for outpatient substance use disorder treatment. Participants with a service dog had 1.12 (SE=0.56, p=0.045) more outpatient substance use visits during follow-up than participants with an emotional support dog. Analyses examining time-varying effects also showed no evidence that service dogs reduced health care use compared with emotional support dogs. We noted some minor indications that having a service dog might lead to more substance use treatment and use of mental health services at various follow-up times, but these effects, although statistically significant, were not consistent across different models or periods and may have been due to multiple comparisons in these analyses. No group differences were observed for non-VA clinic visits, overnight hospital visits, or emergency department visits, with ≥80% of participants reporting receiving all or most of their outpatient care at VA during the follow-up.

Of the 181 participants paired with a study dog, 158 (87%) had at least one refill for antidepressants, 38 (21%) for antipsychotic medications, 41 (23%) for benzodiazepines, and 41 (23%) for other hypnotics and sedatives. Participants with a service dog had a 10-percentage-point (SE=0.03, p=0.001) greater adherence to antidepressant use (

Table 4) and tended to have decreased use of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics and sedatives. More than 90% (N=170) of participants reported using no medications outside of VA prescriptions during the follow-up.

No differences between the two groups were observed in employment and productivity end points at 18 months (see the online supplement). At assignment to a study group when completing the WPAI, 35% of participants in the emotional support dog group reported working and 24% of the service dog group reported working.

In sensitivity analyses, including imputation models for the intent-to-treat population of 227 randomly assigned participants, results were largely consistent with the main analysis, with a few exceptions. These exceptions, however, may have resulted from multiple comparisons, rather than from any notable findings. All sensitivity analyses and models are available in the VA reports to Congress (see the online supplement).

Discussion

In this trial, to our knowledge the first of its kind to directly compare the effectiveness of service dogs and emotional support dogs, we found no significant differences between participants paired with a service dog versus an emotional support dog in the primary outcomes of overall functioning and quality of life over an 18-month follow-up period. We observed an approximately 3.7-point greater reduction in PTSD symptoms (assessed with the PCL-5) over time among participants with a service dog versus an emotional support dog. At month 18, PCL-5 scores were 31.7 and 35.2 for those paired with a service dog and emotional support dog, respectively. Although a PCL-5 score of 31 is a clinically relevant threshold associated with probable diagnosis of PTSD, scores <31 represent a symptom burden that may not require clinical intervention (

50). Because the mean PCL-5 score for participants with a service dog remained slightly above 31, we could not substantiate that service dogs have a demonstrable clinical advantage over emotional support dogs for PTSD. The symptoms in a larger proportion of veterans paired with a service dog no longer met criteria for a PTSD diagnosis by CAPS-5 standards at study completion, although not significantly so (28% in the service dog group vs. 24% in the emotional support dog group). Unsurprisingly, self-reported measures of PTSD (i.e., on the PCL-5) indicated a more robust response than the objective measure (i.e., CAPS-5), findings that likely reflect veterans’ overall perception of greater benefit of service dogs for alleviating PTSD symptoms. Additionally, we noticed a trend toward a potentially greater reduction in suicidal behavior and ideation with longer pairing time for participants with a service dog versus an emotional support dog, although longer follow-up is needed to determine whether this finding persists beyond 18 months. Because both groups had improvements in some outcomes, and a small change in PTSD symptom severity was observed in the service dog group, this study’s results will need to be carefully considered in light of the cost of providing service dogs to veterans with PTSD.

Several strengths of our trial design addressed critiques of previous studies (

25,

27,

28,

51,

52). Specifically, past trials were either underpowered or did not detail the intervention effect (e.g., type and amount of dog training, pairing duration, and effectiveness and quality of human-dog bond), select robust outcome measures, control for bias, or provide consistent and detailed data collection methods. Outcome measures were specifically selected to examine a breadth of common PTSD problems, with multiple data collection points over 18 months to power the time-dependent models. To further reduce variability, we used contract requirements for dog health, soundness, and training, as well as consistent proofing (i.e., a performance evaluation of service dogs or emotional support dogs against contract training standards) procedures by VA trainers, and adhered to practices previously reported by Yarborough et al. (

52).

This study, the largest examination to date on the impact of service dogs on PTSD, assessed a multitude of clinically relevant PTSD outcomes, and its findings are consistent with findings by O’Haire and Rodriguez (

25) showing an improvement in PCL-5 scores. We specifically addressed concerns raised by Yarborough et al. (

51) by including the CAPS-5 score in our analyses and increasing the duration of follow-up with appropriately matched individuals in a control group. Finally, similar findings have emerged across the literature, notably that veterans with PTSD who receive service dogs remain engaged in treatment, are more socially engaged, and derive benefit from the dogs’ ability to deescalate PTSD symptoms by performing specific tasks. Although not all treatments are available, acceptable, or effective for all veterans, another treatment modality that is beneficial and welcomed by veterans is important.

In summary, we found no evidence that a service dog or emotional support dog worsened PTSD or its recovery. Future work should examine mechanisms by which a service or emotional support dog has an impact on patient functioning, such as by directly reducing PTSD symptoms (e.g., arousal or avoidance), indirectly reducing symptoms through improved treatment engagement (e.g., in psychotherapy) or adherence (e.g., to pharmacotherapy), or by enabling veterans to overcome challenging situations in the presence of such symptoms.

Limitations of this study included the inability to have participants be blind to dog type and the lack of a control group. A placebo-controlled design would not only create ethical challenges but could raise problems with appropriate analysis, because it might introduce other biases that cannot be readily mitigated. It is unknown whether the study results can be generalized to nonveteran populations.

Conclusions

In this trial, we observed no significant differences in primary outcomes between participants paired with service dogs and those paired with emotional support dogs. However, participants paired with service dogs had a statistically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms and tended to have a potential improvement in suicidal behavior and ideation compared with participants with emotional support dogs. The design and implementation of studies of this nature are complex; however, by combining the findings of this study with those of previous studies, real benefits are possible for veterans with PTSD. Pairing such veterans with service dogs can complement existing evidence-based treatments and may increase levels of treatment engagement and reduce PTSD symptoms.