Second-generation antipsychotic medications account for 96% of pediatric outpatient antipsychotic prescriptions (

1) and are used to manage a wide range of mental health conditions among adolescents. These conditions include psychotic symptoms, affective disorders, and disruptive behaviors (

2). Second-generation antipsychotic medications, however, are associated with adverse cardiometabolic effects, such as obesity (

3–

7), dyslipidemia (

4,

7), and dysglycemia (

7,

8). Given the downstream associations of mental illness and early metabolic dysregulation with later cardiovascular health (

9), early detection and intervention to address cardiometabolic risk factors of dysglycemia and dyslipidemia among second-generation antipsychotic medication–treated youths are key parts of clinical care.

Clinical guidelines, including those from the American Diabetes Association and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, recommend routine cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring (glycemic and lipid tests) of youths during second-generation antipsychotic treatment (

10), but rates of monitoring have remained low (ranging from 11% to 31%) (

11–

13), even after release of the guidelines. In 2015, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (

14) implemented the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measure for annual glycemic and lipid monitoring for youths taking an antipsychotic medication. Quality metrics are factored into financial and reputational incentives for health care systems, encouraging increased performance in key health care quality domains (

15). However, recent data that might reflect the impact of clinical guidelines and HEDIS metrics are lacking. The most recently published data (collected in 2016–2017) (

16) suggest persistently low monitoring, with completion rates of only 26%–30%.

In an integrated health care delivery system serving youths with diverse sociodemographic characteristics, who initiated second-generation antipsychotic treatment in 2013–2017, we sought to examine changes in cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring over time in order to assess whether monitoring rates differed by patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Despite known racial-ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring among second-generation antipsychotic medication–treated adults (

17,

18), monitoring data for youths of diverse racial-ethnic backgrounds are lacking, limiting our understanding of the potential contribution of low monitoring to poor cardiometabolic health among these already vulnerable young patients. Similarly, previous studies, which focused on a narrower subset of behavioral health diagnoses, did not adequately capture the diagnostic heterogeneity among contemporary cohorts of second-generation antipsychotic medication–treated youths (

2). Because youths with differing behavioral health profiles interact with the health care system in divergent ways, approaches to ensuring guideline-concordant monitoring for these youths will likely need to be tailored to their needs.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This was a serial cross-sectional analysis of electronic health record (EHR) data for 4,568 youths initiating second-generation antipsychotic medication treatment during 2013–2017 in Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated health care system serving >4 million socioeconomically and clinically diverse patients. KPNC patients are representative of the Northern California population, except for those at the lowest and highest incomes (

19). Patients may enroll in KPNC through health insurance plans, including employer-based coverage, Medicare, Medicaid, and health insurance exchanges. The KPNC Institutional Review Board approved the study, with a waiver of consent. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

Youths, ages 10–21 years, were included if they had two prescription fills of one of the following second-generation antipsychotic medications within a 12-month window during 2013–2017: aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, ziprasidone, asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, or paliperidone. The first prescription date was considered the index date. Additional inclusion criteria were no pregnancy and continuous KPNC enrollment and drug coverage for the year before and 2 years after the index date, allowing for brief lapses in enrollment (i.e., no more than a total of 3 months). To constrain the cohort to youths with new second-generation antipsychotic prescriptions, we excluded youths with any antipsychotic medication fill during the year before the index date. The total observation range for this study was January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2019.

Measures

Patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, health care utilization, and cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring were extracted from the EHR. Racial-ethnic categories were White; Black or African American (Black); Hispanic or Latino (Latino); Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (AANHPI); and another or unknown race-ethnicity. We also assessed age, gender, Medicaid insurance, and median annual neighborhood income (income was based on census tract data for the youth’s residential address; ≤$50,000 was considered low income).

Mental and behavioral health diagnoses were considered present at baseline if documented in the EHR 1 year before and after the index date (2 years surrounding the index date; see Table S1 in the online supplement to this article for the list of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used for classifying diagnostic groups). We constructed a hierarchical variable capturing presence or absence of serious mental illness according to three categories: any psychotic disorder, any bipolar disorder, and neither of the above. We additionally measured the following four dichotomous indicators representing presence or absence of nonbipolar affective disorder (i.e., major depression or anxiety disorder): substance use disorder; attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; developmental, intellectual, or disruptive disorder; and other behavioral health diagnosis—these diagnostic categories were not mutually exclusive. By using pharmacy dispensation records, we identified an index second-generation antipsychotic prescription on the basis of two documented fills of a given antipsychotic type. Obesity status was determined by using age-adjusted body mass index (BMI) percentiles during the year before the index date, with the 95th percentile indicating obesity for youths ages 10–19 and a BMI of ≥30 indicating obesity for youths ages 20–21 (coded as observed or not observed). Presence of a comorbid cardiometabolic condition was defined as any ICD-10 diagnostic codes or laboratory results (see Table S2 in the online supplement) indicating prediabetes, diabetes, hypertension, or dyslipidemia. Behavioral health (e.g., psychiatry or addiction medicine) and primary care (e.g., internal or family medicine, obstetrics, gynecology, or women’s health) utilization were for the year after antipsychotic initiation.

The primary outcome was presence of cardiometabolic monitoring laboratory results, defined as having both glycemic and lipid tests performed within 2 years following the index date (follow-up). We selected a 2-year follow-up window to include laboratory results occurring any time during the calendar year after the index date. We also assessed monitoring rates within 1 year after the index date. Glycemic testing was defined as a fasting glucose serum or glycosylated hemoglobin test. Lipid testing was defined as a triglyceride or cholesterol test.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square statistics to describe rates of glycemic and lipid testing and to assess differences by sociodemographic characteristics. To assess time trends in monitoring rates, we used a modified Poisson regression framework to estimate risk ratios (

20,

21). We first estimated a generalized linear model including the year of antipsychotic medication initiation, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and health care utilization. To account for effects related to geographic or site-specific intercorrelation, we specified a generalized estimating equations model including the same variables but additionally accounting for clustering by medical facility service area. We also assessed potential sociodemographic moderators of the time effect on monitoring by estimating five additional generalized estimating equations models to examine interactions between year of antipsychotic initiation and each sociodemographic characteristic: gender, age (continuous), race-ethnicity, median neighborhood income, and insurance type.

Because of the data set size and multiple comparisons, we assessed statistical significance by using a conservative alpha of 0.002 and 99.8% CIs, consistent with a Bonferroni correction for 29 variables used in the regression models. Analyses were conducted in Stata, version 15.1.

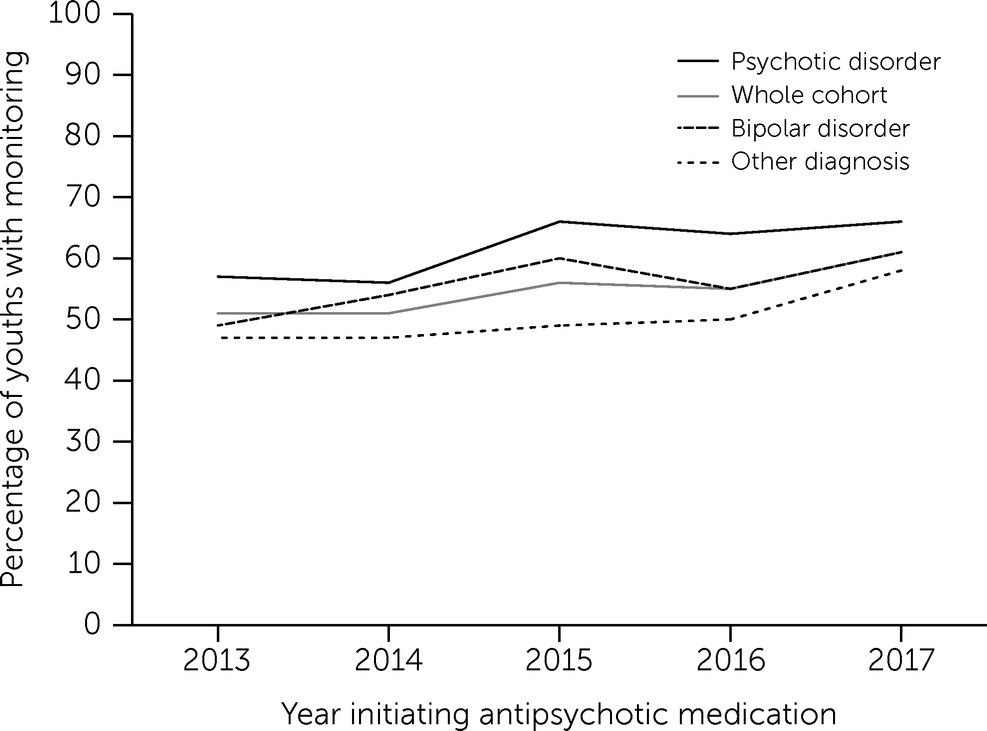

Discussion

Regular glycemic and lipid monitoring are recommended for youths taking antipsychotic medications, and although these guidelines have been reinforced with quality metrics (

10,

22), low monitoring rates have persisted (

16,

23). We sought to examine change in cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring over time and to assess whether sociodemographic and clinical factors were related to receipt of monitoring. In a large integrated health care delivery system, we found that monitoring rates increased modestly, by 5% with each medication initiation year for each given cohort, after the analyses were adjusted for patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and health care utilization. Our findings that only 41%–54% of youths completed the recommended monitoring within 1–2 years of initiation of antipsychotic medication suggest a need for strategies to increase the reach of this recommended disease prevention practice.

Consistent with findings from previous research (

12,

13,

24), youths with serious mental illness and those with more frequent contacts with the health care system were more likely to be monitored for cardiometabolic risk. Unlike earlier studies, our analysis included participants ages 18–21 years, and we found that these transition-age youths were less likely than younger adolescents to complete monitoring. Screening was less common among White and Black youths and more common among Latino and AANHPI youths. These racial-ethnic differences were not statistically significant once we accounted for potential similarity within areas served by medical facilities, suggesting a need to examine geographic or facility-specific factors to understand these differences. Evidence (

17,

25) suggests that Hispanic and Latino, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Black individuals face earlier risk for type 2 diabetes, both in the general population and among those with serious mental illness. This elevated risk further underscores the need to conduct early, guideline-concordant cardiometabolic monitoring.

Past research has found low cardiometabolic monitoring rates among individuals treated with antipsychotic medications (

23,

26) and that increased monitoring is associated with quality-improvement interventions (

27). Within the health system of this study, quality-improvement methods were under way during the study period in response to HEDIS metrics seeking to improve cardiometabolic screening through population-based methods (e.g., by using EHR data to track patients’ completion of monitoring and send screening reminders to patients and clinicians). Despite these efforts, we found that 1–2-year monitoring rates among these youths were lower than the approximately 60% of the target population achieved in studies evaluating quality-improvement approaches to increase screening of patients treated with antipsychotic medications (

27). To close this gap, future research seeking to increase cardiometabolic monitoring should consider patient-level sociodemographic and clinical variables identified in the present study.

Having a psychotic disorder was associated with greater likelihood of receiving cardiometabolic monitoring, a finding that may reflect the particular focus of quality metrics (

14) on improving cardiometabolic disease screening and monitoring for people with schizophrenia. Health system quality processes may have been optimized for individuals with psychotic disorders. Another reason for greater monitoring could be the severity of impairment among adolescents with psychotic disorders compared with those with severe mood disorders (

28). Youths with psychotic disorders may have been more dependent on adult caregivers who would have been more likely to bring youths to laboratory visits. Risperidone prescription, also positively associated with monitoring in the current study relative to quetiapine, may also have been a marker of dependence on caregivers, because risperidone is often prescribed for challenging behaviors across a range of mental disorders (

29,

30). Targeted clinical strategies may be needed to raise monitoring rates among youths with nonpsychotic mood disorders, which are prevalent among adolescents prescribed antipsychotic medications (

2) and are correlated with long-term cardiometabolic disease risk (

31–

34).

We also observed a lower likelihood of cardiometabolic monitoring associated with substance use disorder, another risk factor for cardiovascular disease and associated increased mortality rates (

35–

37). Youths with diagnosed substance use disorder may receive more of their behavioral health care in specialty addiction rather than in other mental health treatment settings. These findings suggest a need to integrate monitoring for cardiometabolic risk factors into addiction services. The association of substance use disorder with lower monitoring persisted after the analyses were adjusted for primary care and behavioral health visit rates; the content of these visits may have differed between youths with a substance use disorder and youths without such disorder, perhaps because providers put less emphasis on cardiometabolic monitoring of youths with substance use disorder.

Obesity, but not other cardiometabolic disease risk factors (e.g., prediabetes), was significantly related to greater monitoring. Obesity may present as a more obvious concern to patients, caregivers, and clinicians, prompting the monitoring (

38). Other cardiometabolic risk factors, such as hypertension, although associated with monitoring of antipsychotic-treated adults (

39), remain underdiagnosed among adolescents (

40,

41). The increasing prevalence of cardiometabolic conditions among youths more generally raises the urgency of cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring, especially among the vulnerable subpopulation of youths treated with antipsychotic medications.

A limitation of our findings was that they may not generalize to youths treated in other regions of the United States or to other health care settings, such as community mental health clinics. As an inclusion criterion, we required participants to fill two prescriptions of a second-generation antipsychotic medication, but we did not examine whether later discontinuation of the medication influenced likelihood of monitoring. In practice, dosage and duration of the antipsychotic medication prescription may affect likelihood of cardiometabolic monitoring, but we did not examine these factors. It was not possible to determine whether the elevated monitoring rates observed among AANHPI and Latino youths would generalize to individuals from these backgrounds who were not served in the study health system. Once we accounted for the geographic area served by medical facilities, AANHPI and Latino race-ethnicity were no longer significantly associated with monitoring. This finding suggested that similarities at the local level explained racial-ethnic associations, but we could not determine whether these similarities were specific to race-ethnicity or were confounded by other variables. Future studies including other large samples of racially and ethnically diverse youths are needed to confirm these associations between race-ethnicity and increased cardiometabolic risk factor monitoring. Our EHR data did not allow for confirmation of the mechanisms that drove greater monitoring among some subpopulations, and these mechanisms should be explored in future research.