Depression and schizophrenia often first occur during adolescence and young adulthood, respectively (

1). However, approximately 32% of individuals with schizophrenia and 56% of people with depression do not receive treatment (

2,

3). Research suggests that barriers to treatment seeking among young people include stigma and embarrassment, poor mental health literacy, and a preference for self-reliance (

4). As such, public and internalized stigma or negative attitudes and beliefs may result in avoidance or reduced treatment seeking (

5).

Therefore, there is a need for interventions to reduce stigma among young people toward people with mental illness and to increase treatment-seeking intention among youths. Prior research has suggested that social contact–based interventions are effective, regardless of age group (

6,

7). These interventions involve interpersonal contact with individuals of a stigmatized group, who share their struggles and recovery, typically in person in classrooms or community centers. Recent studies have shown that video-based interventions have similar efficacy to in-person interventions and are easier to disseminate (

8).

However, extant video-based studies have had limitations. First, a recent review found that video interventions last 20–60 minutes or even days (

9), whereas younger audiences may prefer shorter content. Second, most studies have included relatively small samples (dozens to hundreds) consisting of narrow and nonrepresentative populations (mostly college students), thus limiting generalizability (

8–

10). Third, an emerging trend in treatment toward the use of online platforms has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, altering content dissemination and increasing remote learning and social media use (

11–

13). Finally, most studies of social contact–based video interventions have assessed stigma immediately postintervention but have lacked follow-up measurement to understand sustained effects (

9,

14,

15).

To address these gaps in the literature, we conducted a series of studies (

16–

21) to examine the effect of brief (73 to 100 seconds each) video-based interventions on stigma and treatment-seeking intention. The studies broached several domains, including psychosis-related stigma (

16–

18), depression-related stigma, transphobia, and help seeking (

19–

21). These studies were conducted among national samples of adolescents (ages 14–18) or young adults (ages 18–30) by using several crowdsourcing platforms. Across all studies, we followed the principle of disconfirming stereotypes by balancing discussion of struggles and symptoms with messages of hope and recovery (

22). We concluded that brief social contact–based video interventions are effective in reducing stigma and increasing help seeking.

Despite this progress, gaps remain. First, production of the traditional brief video is associated with substantial financial and time costs because it includes interviewing, filming, lighting, sound, and editing processes. Alternatively, young individuals usually film their stories on their own recording devices in selfie style. Selfie-style videos may also appeal more to a young audience because social media influencers often use the medium to connect with their audiences. Second, youths often consume their preferred content on social media platforms (

23). Our prior videos lasted 73–100 seconds, longer than the recommended duration limit for Instagram and TikTok of 60 seconds. Two crucial questions emerged from our findings: Would a selfie-style video yield the same effect as a traditionally filmed video? Would shorter versions of these videos yield the same effect?

To answer these questions, we designed two studies, differing in stigma domains, age of participants, and outcome measures, to compare traditional, professionally filmed video (“traditional”), selfie-style video (“selfie”), and control groups in each study. In study 1, young adults ages 18–30 viewed a 75-second video of an individual with psychosis telling her story. The two intervention groups (traditional and selfie) viewed videos with the same content and length and were assessed at baseline, postintervention, and 30-day follow-up. In study 2, adolescents ages 14–18 viewed brief videos of a young individual with depression telling her story. In study 2, we also compared longer and shorter video lengths; the traditional video lasted 102 seconds, whereas the selfie video lasted 58 seconds. Assessments were conducted at baseline and postintervention. We hypothesized that in both studies the intervention videos would show greater efficacy than the control condition and that there would be no difference in efficacy, as assessed with noninferiority analyses, between the traditional and selfie videos.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

In both studies, recruitment took place in September and October 2021. We chose to focus on adolescents and young adults because of their stage of identity consolidation, a developmental stage characterized by a strong need for autonomy, sense of competence, and social acceptance (

24). The age ranges also overlap with the median age of onset of psychosis (young adults) and major depressive disorder (adolescents).

Study 1: young adults.

We recruited participants by using Prolific, a crowdsourcing platform widely used in behavioral and medical research (

25). We required participants to be English-speaking U.S. residents and to be 18–30 years old. Participants were compensated $2.20 for study participation. The New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the project (protocol 8054).

Study 2: adolescents.

Participant recruitment was conducted by using CloudResearch (

26), a crowdsourcing platform with demonstrated validity across tasks and countries. We included only English-speaking youths, ages 14–18, living in the United States. Participants were compensated $4.50 for study participation. This study was approved by the Yale Human Investigations Committee, Yale University’s IRB (protocol 2000028980_a).

Intervention

Study 1: young adults.

We compared the efficacy of two brief videos, 75 seconds each, and a nonintervention control. The intervention videos presented the story of an empowered young woman with schizophrenia who described her psychotic illness and her struggles and introduced themes of recovery and hope. One video was filmed in traditional fashion, with support from a documentary video production company and professional lighting, sound, and editing—an intervention proven to be effective in reducing stigma (

18). The second video had identical content but was filmed by the participant (i.e., selfie) with her smartphone, with no editing, guidance, or instruction, as if the participant were about to upload her self-made video onto a social media platform. We conducted assessments at baseline, immediately postintervention, and at 30-day follow-up.

Study 2: adolescents.

We compared the efficacy of a traditional, studio-produced, 102-second video, which was previously found to be effective in reducing depression-related stigma and increasing help-seeking intention (

19), with that of a shorter (58 seconds), selfie version of the same content. Both videos were based on the same script, with the same 16-year-old adolescent (a professional actress) sharing her personal story of coping with depression and suicidal thoughts and discussing how treatment had helped her. The traditional video was filmed and edited professionally, and the selfie video was filmed by the adolescent herself, with no editing. In the control video, the same adolescent did not discuss mental health, but instead talked about her family and interests. We conducted assessments at baseline and immediately postintervention.

Assessment methodology.

To verify the validity of the study results, we applied several methods in order to exclude invalid participants during data collection. First, in designing the study, we added a timer to ensure that participants had sufficient time to read the instructions and watch the video before the “next” button appeared. Second, we excluded participants who failed our attention verification questions (e.g., “In the following question, please choose the second answer”). Third, we scanned the responses to exclude participants who answered the assessment more than once. Before initiating the survey, participants reviewed an informed consent or assent page (parental consent was waived). We directed individuals who agreed to participate to complete the study survey by using Qualtrics, a secure, online data collection platform.

Instruments

Study 1: young adults.

As in our previous studies (

16–

18), we used a questionnaire to assess public stigma toward people with schizophrenia across five domains (

27–

30): social distance (6 items), stereotyping (4 items), separateness (4 items), social restriction (3 items), and perceived recovery (2 items). Two items assessed whether the participant had a friend or family member with serious mental illness and, if so, their level of intimacy with that individual (

31).

Study 2: adolescents.

In study 2, we measured stigma toward depression with the Depression Stigma Scale (DSS) (

32) and measured treatment-seeking intention with the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) (

33), similar to our previous studies (

19–

21).

Data Analysis

We calculated sample size, seeking to discriminate at least a medium effect size (Cohen’s d>0.30) between the intervention groups and control group and between intervention groups. By using noninferiority analyses and on the basis of the primary outcomes and expected effect size of 0.30, we determined that a sample size of N=300 for each group in study 1 (young adults) and N=200 for each group in study 2 (adolescents) would provide adequate power (>0.80) to detect α<0.05. We used Pearson’s chi-square test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare demographic variables across study arms. In study 1, repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to compare mean stigma scores on each domain subscale across three study arms (traditional, selfie, and control) and three time points (baseline, postintervention, and 30-day follow-up). One-way ANOVAs were then used to compare changes in stigma scores between baseline and postintervention and between baseline and 30-day follow-up across the three study groups. In study 2, paired t tests were used to compare DSS and GHSQ mean scores from baseline to postintervention within study groups (traditional, selfie, and control), and independent t tests were used to compare between-group changes. For all t tests, we used a Bonferroni correction and considered only results with p<0.01 to be significant (i.e., adjusted for at least 5 comparisons). We conducted all statistical analyses with IBM SPSS, version 28.0.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Study 1: young adults.

After we excluded 47 (5%) participants who failed validity tests, 895 completed the baseline assessment before being randomly assigned at a 1:1:1 ratio to one of the three study groups. Of those, 856 (96%) completed the postintervention assessment, and 640 (72%) completed the 30-day follow-up assessment (a flow diagram is available in the

online supplement to this article). Baseline characteristics did not differ between those who did and those who did not complete the assessments, and sociodemographic characteristics did not differ across study groups (

Table 1). Mean±SD participant age was 23.9±3.7 years (range 18–30). Almost half of respondents were women (N=428, 48%). A total of 124 (14%) participants self-identified as Black, 124 (14%) as Hispanic, 579 (65%) as White, 113 (13%) as Asian, 7 (1%) as Native American, and 72 (8%) as other.

Study 2: adolescents.

After we excluded 92 (13%) participants who failed validity tests, 637 were randomly assigned at a 1:1:1 ratio to one of three study arms. Six hundred twenty-five (98%) completed the postintervention assessment (a flow diagram is available in the

online supplement). Baseline characteristics did not differ between those who did and those who did not complete the assessments, and sociodemographic characteristics did not differ across study groups (

Table 1). Mean participant age was 17.1±1.1 years (range 14–18), and almost half of participants were female (N=309, 49%). A total of 142 (22%) participants self-identified as Black, 127 (20%) as Hispanic, 356 (56%) as White, 53 (8%) as Asian, 9 (1%) as Native American, and 71 (11%) as other.

Intervention Effects

Study 1: young adults.

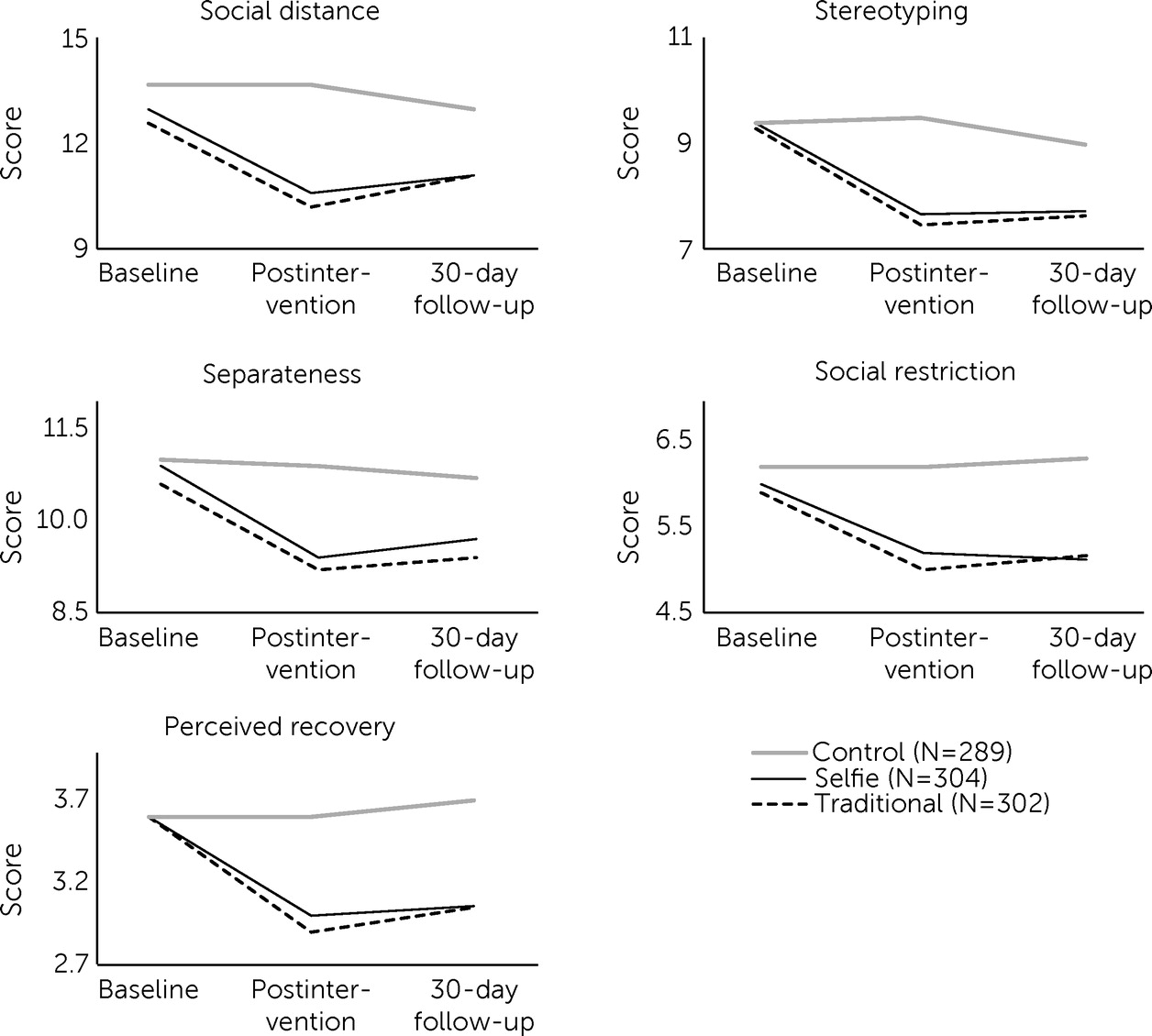

Study groups significantly differed in outcomes. A 3×3 group × time ANOVA showed that mean stigma scores decreased over time in the two intervention groups across all five stigma domains: social distance (F=25.1, df=2 and 4, p<0.001), stereotyping (F=38.8, df=2 and 4, p<0.001), separateness (F=17.0, df=2 and 4, p<0.001), social restriction (F=22.9, df=2 and 4, p<0.001), and perceived recovery (F=13.2, df=2 and 4, p<0.001).

Figure 1 presents the mean score curves of the study groups over time, stratified across each of the five stigma domains, showing that the control group essentially did not demonstrate any change, whereas both intervention groups did. One-way ANOVAs showed a significant between-group change from baseline to postintervention and from baseline to 30-day follow-up across all five stigma domains. Post hoc tests showed that selfie videos were not inferior to traditional videos, with no significant difference between the two but significant differences between each intervention video and the control group. Cohen’s d effect sizes ranged from 0.47 to 0.76 for changes from baseline to postintervention and from 0.31 to 0.76 for changes from baseline to 30-day follow-up.

Study 2: adolescents.

As in our previous study (

19), the study groups significantly differed in outcomes. A univariate ANOVA showed a significant between-group effect for mean DSS total scores between baseline and postintervention (F=8.0, df=1 and 2, p<0.001).

Table 2 presents the DSS items and compares baseline with postintervention mean and total scores for the traditional (N=220), selfie (N=212), and control (N=205) groups. Cohen’s d effect sizes ranged from 0.13 to 0.47 for individual DSS items and from 0.24 to 0.26 for DSS total scores. To better understand the outcome differences across study arms, we used independent t tests to compare DSS pre-post changes among the traditional, selfie, and control groups. The traditional (1.4±2.7) and selfie (1.3±3.0) video groups significantly differed from the control video group (0.4±2.1) (t=3.5, df=408, p<0.001 and t=3.6, df=413, p<0.001, respectively), but the traditional and selfie videos did not significantly differ from each other.

Table 3 presents the GHSQ scores. We found a significant increase in intention to seek help from a telephone helpline and a decrease in unwillingness to seek help from anyone in both the traditional and selfie video groups. In addition, we found an increase in intention to seek help from a parent in the selfie video group. We found no change in help-seeking intention in the control group. Cohen’s d effect sizes ranged from 0.14 to 0.33.

Discussion

We tested the efficacy of brief videos to reduce stigma toward people with psychosis among 895 young adults (study 1) and to reduce stigma toward people with depression and increase treatment-seeking intention among 637 adolescents (study 2) in two RCTs. As hypothesized, these 58- to 102-second videos, regardless of filming style (traditional or selfie), had significantly greater impact than the control condition in reducing illness-related stigma and increasing treatment-seeking intention. In hopeful, uplifting stories, the intervention videos presented young individuals who struggled with mental illness and successfully engaged in treatment. These findings replicate and extend our previous findings (

16–

21) by showing reduced stigma as a result of viewing shorter videos and videos filmed in a selfie style. Despite a slight rebound after 30 days, these reductions were preserved over time. Our work is consistent with the current literature emphasizing the potency of contact-based interventions in changing young people’s perceptions about mental illness and treatment (

7,

10).

We found no difference between the efficacy of traditional and selfie videos, despite differences in study characteristics (e.g., video lengths, presenter with lived experience vs. actor, recruitment methods, assessment tools, study population [young adults vs. adolescents]), thus emphasizing the generalizability of the results. The implications are clear: traditional videos, which require interviewers, photographers, lighting, sound, and editing processes, cost more and take longer to create than selfie videos yet have no advantage over them. In addition, a growing body of literature supports the use of smartphone and selfie videos in medicine. For example, selfie videos are used to detect and monitor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (

34), to intervene to change toothbrushing technique (

35), and to develop proficiency in clinical interviewing for medical students (

36). In psychiatry, photographs and narratives have been used to communicate the experiences of people with mental illness and engage in a critical dialogue to inform social action (

37). For example, Cabassa et al. (

38) demonstrated the efficacy of photovoice, a participatory method that empowers people with severe mental illness by giving them cameras to document their experiences of perceived recovery. Tippin and Maranzan (

39) showed the efficacy of photovoice-based video in reducing mental illness–related stigma among 303 undergraduate university students.

Selfie-based interventions offer a culturally consonant, technically simpler, and cheaper alternative to traditional videos. Adolescents and young adults create selfie videos anyway—why not harness them to reduce stigma? Although concern has been raised that sharing personal stories through selfies could lead to criticism and shame, especially on social media (

40,

41), data point to the potential of social media to combat stigma, raise awareness of mental health problems, and emphasize the societal benefits that can be facilitated via such platforms (

42). Young individuals, who already share personal stories on their recording devices using selfie videos, can create content that may reduce stigma. Future intervention research should focus on guiding and instructing adolescents and young adults on how to create stigma-reducing content.

Why explore the optimal length for social contact–based video interventions? We previously showed the efficacy of 73- to 100-second videos in reducing stigma and increasing treatment-seeking intention (

16–

21). Study 2 is the first to directly compare a briefer, 58-second video with a longer intervention video, demonstrating similar efficacy. Brevity has advantages. Leading social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, which youths often use (

23), recommend limiting video content to 60 seconds. Social media influencers often use selfie videos to connect with the young audiences who follow their opinions and advice. For example, a recent study (

43) examined the association between Twitter content of social media influencers and suicide. The authors showed that tweets describing suicide deaths or tragic news stories about suicide may be harmful, whereas those that present suicide as undesirable or preventable may be helpful. These results suggest that social media influencers can positively affect youths’ lives via their social media communications and can be a potential avenue for intervention. Future studies should examine the efficacy of brief videos filmed by a social media influencer and uploaded to a social media platform to reduce mental health stigma and increase engagement with treatment at a larger, population-wide level.

Our study had several limitations. First, findings may be limited to users of crowdsourcing platforms, who might not be fully representative of the general population, thus limiting generalizability. More studies are needed, preferably ones that incorporate social media use. Second, our study assessed only attitudes about stigma and treatment seeking, the reporting of which is subject to social desirability (

44). Future studies should measure real-world behaviors and how many participants sought treatment. Last, although one study evaluated 30-day aftereffects, the second study evaluated only the video’s immediate impact. Future research should examine longer-term sustainability of stigma-reduction interventions among adolescents.

Conclusions

These two RCTs replicated and extended our previous findings by showing the positive effect of brief videos, both traditional and selfie style, on reducing stigma associated with psychosis (young adults) or depression (adolescents) and increasing treatment-seeking intention among adolescents. Traditional and selfie videos showed similar efficacy, at a duration of 102 or 58 seconds, respectively (study 2). These findings suggest the potential for the use of brief selfie videos on social media platforms to increase the likelihood that youths will seek services and to improve access to care among young individuals with mental illness. These improvements are especially important given the increased rates of mental illness among youths since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Future studies should explore the effects of brief videos presented by social media influencers on mental health stigma and treatment engagement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the video presenters, who shared their stories and contributed to stigma reduction.