Individuals with serious mental illness are at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 and experience increased mortality once they are infected (

1,

2). COVID-19 vaccines help to prevent transmission and reduce mortality among infected patients (

3). In New York State, 95% of adults received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, and more than 70% received two doses, by February 2022, but individuals with serious mental illness have lower vaccination rates than the general population (

4,

5). Despite early efforts to prioritize COVID-19 vaccinations for patients with serious mental illness, little is known about COVID-19 vaccination rates in this population (

5). Characterizing COVID-19 vaccination rates in high-risk groups that are vulnerable to health inequities can help inform vaccine outreach efforts and infection control policies in psychiatric hospitals and other institutional settings.

In this brief report, we examined vaccination rates for patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric units at a large health system during the first 6 months of COVID-19 vaccine eligibility for adults in New York State. We then compared vaccination rates in the psychiatric population with those of patients admitted to medical and surgical units within the same health system and with the overall vaccination rates in the regional catchment area, which includes New York City, Long Island, and the Mid-Hudson region of New York, within the same period (

4). We hypothesized that during the first 6 months of universal adult vaccine availability, adults admitted to psychiatric units would have lower vaccination rates than patients admitted to medical and surgical units and the population of the regional catchment area. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine COVID-19 vaccination rates in a large inpatient psychiatric cohort.

Methods

We extracted data from electronic medical records (EMRs) of 12,714 unique inpatients at two facilities within a large health system in New York State: an 862-bed tertiary care academic medical center providing comprehensive general medical and surgical care and a 220-bed freestanding psychiatric hospital within the same regional catchment area. The sample included New York State residents ages ≥18 years who were admitted between April 6, 2021, and September 30, 2021. This time frame corresponded to the first six calendar months of universal adult COVID-19 vaccine availability in New York State. Extracted data included demographic characteristics (age, sex, race-ethnicity), ICD-10 codes corresponding to general medical and psychiatric diagnoses, and vaccination status at the time of hospital admission.

Patients were considered vaccinated if they had at least one dose prior to admission. We chose a single vaccination dose as the outcome of interest for two reasons. First, at the beginning of the study period, some patients were eligible only for the first of a two-dose series. Second, others received a Johnson & Johnson vaccine that was given as a single inoculation. Vaccination status was determined by using two methods. Initially, vaccination status was confirmed in the New York State Immunization Information System (NYSIIS) database, which records all state COVID-19 vaccine administrations (

6). Any patient listed in NYSIIS was considered vaccinated. Because patients residing in New York State may have been vaccinated in a different state and thus would not be listed in NYSIIS, we also extracted data from the health system’s EMRs, which contained patient self-report of vaccination status. Ninety percent of the vaccination data came from the NYSIIS database.

We calculated vaccination rates from April 6, 2021, to September 30, 2021, for psychiatric and for medical and surgical inpatients overall, by month, and within demographic groups and obtained vaccination rates for the overall regional catchment area from the New York State Department of Health (

4). If a patient was admitted to either the medical facility or psychiatric facility more than once, we counted only the first admission in the analysis because the patient may have been vaccinated during the first admission. Similarly, if a patient was admitted to both the medical and surgical facility and the psychiatric facility during the study period, we included only the initial admission. In the overall sample, 1.4% of patients (N=181 of 12,714) were admitted to the medical facility and then transferred to the psychiatric facility in a single admission. For the purpose of this analysis, these patients were considered part of the medical cohort. A separate analysis with these 181 patients considered as part of the psychiatric cohort did not lead to meaningful changes in our results or conclusions.

Finally, we used log-binomial regression to assess differences in vaccination rates after adjusting for patient characteristics (age, sex, race-ethnicity, presence of general medical and psychiatric conditions). The project was approved by the institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medicine of Cornell University.

Results

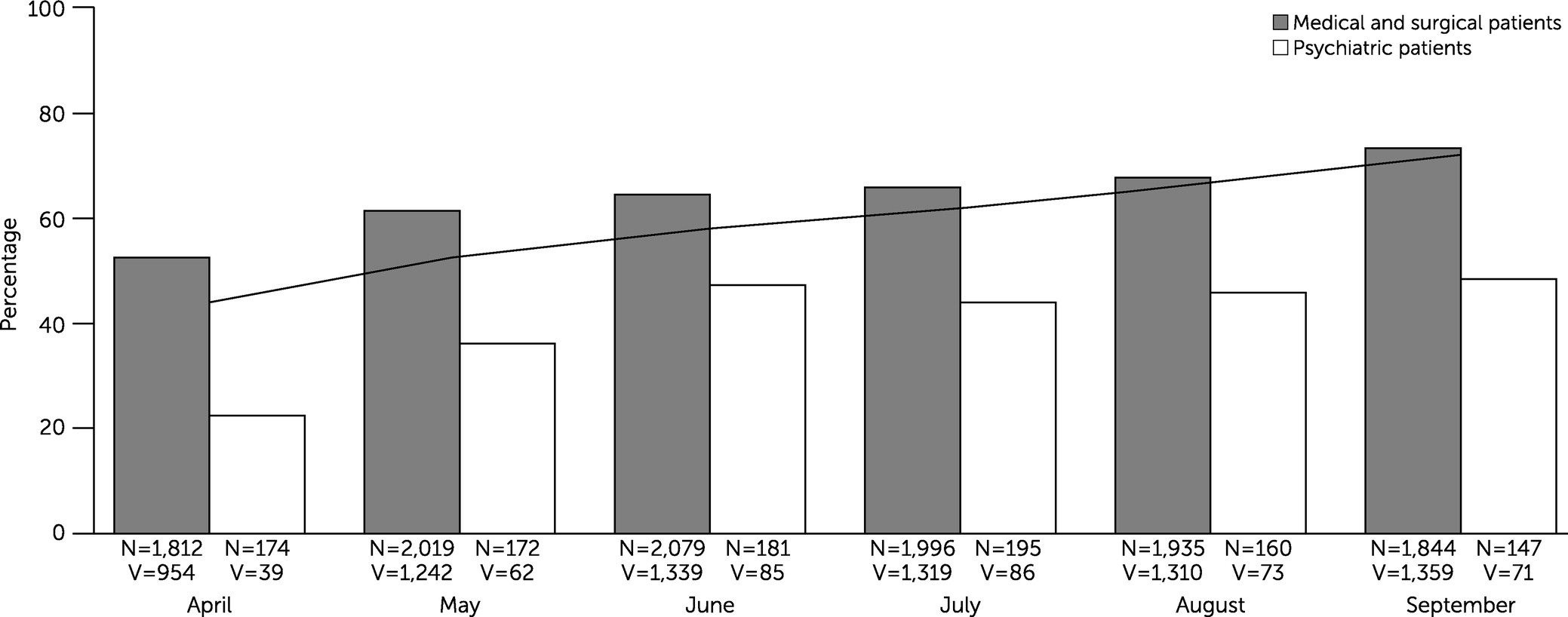

During the first 6 months after COVID-19 vaccines were universally available for adults, 40% (N=416 of 1,029) of psychiatric inpatients in our sample had at least one COVID-19 vaccination, whereas 64.4% (N=7,523 of 11,685) of medical and surgical inpatients had at least one vaccination. Vaccination rates among medical and surgical inpatients increased every month during the study period, from a low of 53% (N=954 of 1,812) in April 2021 to 74% (N=1,359 of 1,844) in September 2021 (

Figure 1). Vaccination rates among psychiatric inpatients plateaued at 47% (N=85 of 181) in June 2021 and never exceeded 50% during the study period.

Among the psychiatric inpatients (N=1,029), a majority had multiple psychiatric diagnoses (three or more diagnoses: N=660, 64%; two diagnoses: N=279, 27%; one diagnosis: N=90, 9%). The broad diagnostic groups among psychiatric inpatients included mood (affective) disorders (N=713, 69%), anxiety disorders (N=676, 66%), substance use disorders (N=665, 65%), psychotic disorders (N=422, 41%), personality disorders (N=284, 28%), developmental disorders (N=59, 6%), and other (N=282, 27%).

Differences in vaccination rates between psychiatric patients and medical and surgical patients were apparent for most age groups (ages ≥65, 66% [N=59 of 90] vs. 78% [N=3,176 of 4,060]; 60–64, 44% [N=21 of 48] vs. 70% [N=582 of 829]; 50–59, 47% [N=62 of 133] vs. 67% [N=841 of 1,264]; 30–49, 35% [N=134 of 378] vs. 57% [N=2,477 of 4,346]; 18–29, 37% [N=140 of 380] vs. 38% [N=447 of 1,186], respectively), both sexes (men, 34% [N=180 of 525] vs. 68% [N=2,793 of 4,094]; women, 47% [N=236 of 504] vs. 62.3% [N=4,730 of 7,589], respectively; missing data, N=2 for the medical and surgical group), and all racial-ethnic groups (Black, 28% [N=65 of 235] vs. 48% [N=692 of 1,442]; Latinx, 41% [N=79 of 194] vs. 54% [N=785 of 1,442]; White, 47% [N=174 of 374] vs. 71.9% [N=3,887 of 5,406]; other, 45% [N=62 of 139] vs. 65% [N=1,059 of 1,622]; not specified, 41% [N=36 of 87] vs. 62% [N=1,100 of 1,773], respectively).

Overall, after we adjusted for differences in patient characteristics, patients admitted to psychiatric services had a significantly lower likelihood of vaccination during the study period (risk ratio=0.78, 95% confidence interval=0.73–0.85, p<0.001) compared with patients admitted to the medical and surgical facility. Sensitivity analyses based on data from psychiatric patients versus medical and surgical patients matched for age, sex, race-ethnicity, and general medical comorbid condition yielded identical results.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study was that during the first 6 months of COVID-19 vaccine eligibility for adults in New York State, psychiatric inpatients at a large health system were less likely to be vaccinated than were medical and surgical inpatients (risk ratio=0.78). Vaccination rates increased every month for the medical and surgical inpatients and for the overall population in the regional catchment area but plateaued for the psychiatric inpatients and never exceeded 50%. These findings are significant for several reasons. The overall lower vaccination rate and plateauing vaccination rate among psychiatric inpatients highlight possible disparities in vaccine access, acceptance, or outreach efforts and identify an at-risk group within a regional population that has benefited from an overall successful COVID-19 vaccination campaign. This was the first study to characterize vaccination rates in a large U.S. psychiatric inpatient sample and to highlight the disparity in vaccination rates for this population.

Individuals with serious mental illness have substantially reduced life expectancy (

7), and persistently low COVID-19 vaccination rates may exacerbate mortality in this patient population. Future vaccine outreach efforts should therefore specifically address the needs of this community. Our findings contrast with an early European report showing similar COVID-19 vaccination rates among individuals with serious mental illness and individuals in the local community (

8). In comparison, our study suggests that there are greater challenges in the United States associated with vaccine hesitancy or access for individuals with serious mental illness and extends the findings of Shahani et al. (

9), showing significant vaccine hesitancy in an inpatient psychiatric population. Additional work is needed to better understand the factors that contribute to low COVID-19 vaccination rates in this population in communities such as ours.

Black psychiatric inpatients had the lowest overall vaccination rate in our sample (N=65, 28%), highlighting the vulnerability of this group. This finding is of particular concern because life expectancy of Black and Latinx individuals has disproportionately decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic (

10), and it underscores the need to build trust and adopt better strategies to improve vaccination efforts in communities of color. Promising approaches include identifying clinicians, clergy, and community leaders from racial-ethnic minority groups to champion vaccination efforts and serve as trusted communication channels (

11).

Our results also help inform institutional infection prevention policies. Although early mitigation efforts were successful in reducing institutional COVID-19 outbreaks (

12), individuals in inpatient psychiatric facilities, homeless shelters, supportive group residences, and correctional settings may remain at high risk even during periods of relatively low COVID-19 transmission in the community (

13). These institutional settings should consider maintaining routine COVID-19 testing, social distancing, face mask mandates, and other interventions for longer than may be deemed necessary for the general population in order to reduce transmission. Psychiatric hospitals should continue to invest in and prioritize COVID-19 vaccination programs for individuals with serious mental illness and formally evaluate vaccine hesitancy as part of comprehensive care. A recent report showing high COVID-19 vaccination rates among patients in an outpatient clozapine clinic that adopted a simple tool to promote vaccination may serve as a model for encouraging vaccination in this population (

14). Inpatient psychiatric settings already have the infrastructure for and personnel who have experience with vaccination programs, as required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for influenza vaccines (

15). Physician and administrative leadership support will be necessary to adopt and expand these readily accessible tools for larger populations.

Major strengths of this study included the large sample and use of data extraction from health system–wide EMRs, which reduce selection bias. Limitations included the use of a single vaccination dose as the outcome of interest and the use of a regional sample, which limits generalizability to areas outside the New York City region. Additionally, our results were drawn from inpatient populations and may not generalize to populations with reduced acuity of psychiatric or general medical conditions. Replication of our findings over longer time frames and in other U.S. regions can further characterize vaccination patterns among individuals with psychiatric conditions.

Conclusions

Despite early recognition of the importance of prioritizing COVID-19 vaccination for patients with serious mental illness, our results suggest that present efforts are inadequate. Psychiatric hospitals, homeless shelters, correctional facilities, and other institutional settings serving many patients with serious mental illness may need to continue infection control practices longer than is necessary for the general population. Greater COVID-19 vaccination efforts are needed to reach desirable vaccination rates in psychiatric populations with acute illness in the New York City region, with a particular focus on building trust and increasing vaccine acceptance and access among Black populations. Additional research is necessary to confirm our findings for outpatients and in other U.S. regions. Improving vaccination rates for individuals with serious mental illness could contribute to the goal of reducing excess medical mortality in this vulnerable population.