Hospital discharge has been described as “confusing and chaotic” (

1) and is a time when patients are at high risk of experiencing medical errors and care discontinuity (

2). Although patients may be harmed when incorrect actions are taken (e.g., patients receiving the wrong medication dose) (

3), they are much more likely to be harmed as a result of errors of omission. For example, failing to schedule a patient’s follow-up appointment for mental health ambulatory services prior to discharge puts the patient at risk of missed treatment, nonadherence, clinical deterioration, and possible hospital readmission (

4). Effective discharge planning practices address these care gaps and include the following elements: timely discharge summary completion, predischarge patient education, medication reconciliation, and a follow-up appointment scheduled to occur shortly after discharge (

5). However, these elements are often implemented inconsistently. Further, patient factors, such as the patient’s attitudes and perceptions, frequent or recent previous admissions, co-occurring diagnoses, socioeconomic status, and housing status, may negatively affect the discharge planning process, particularly in the absence of standardization (

1).

A patient’s discharge from acute psychiatric services represents an opportunity to codevelop with the patient a comprehensive, evidence-based plan of care to promote continuity of care and ensure that any improvements achieved during hospitalization continue after discharge. Standard discharge practice includes the preparation of a discharge summary that is sent to the outpatient provider. A proposed new standard discharge practice is the preparation of a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS), which is a patient-facing version of the discharge summary that provides the essential information a patient needs to be an active participant in their discharge plan (

6). The PODS process brings the patient into the information loop and has been successfully implemented in a wide range of inpatient care settings, including acute care and rehabilitation services (

6), and the process has been found to be associated with patients’ increased self-efficacy in managing their conditions (

7,

8). The PODS template standardizes the information provided to patients prior to discharge, and it includes the reason for admission, current medications, scheduled follow-up appointments, and reasons to seek further help or reassessment. Additional resources, such as information about self-help groups or online services, may also be provided.

Although the focus of a PODS procedure is on patient education during the discharge period, the standardized process of completing the PODS template may have the added benefit of improving related discharge care processes, such as medication reconciliation (i.e., the process of comparing current medication orders with what the patient has been taking to ensure that there are no omissions, duplications, dosing errors, or drug interactions) and structured discharge planning.

Prior to this intervention, postdischarge follow-up appointment attendance at our institution (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health) was poor (weighted moving average=24.7% within 30 days), and return visits to the emergency department were not uncommon (9.6% within 30 days). The standard process was to provide a prescription and an appointment card to the patient. The attending physician also completed a discharge summary for the primary care provider; this task was completed promptly less than 40% of the time. Given that our hospital’s discharge process did not engage patients in a consistent or patient-centered way, we thought a PODS process could improve discharge outcomes, and we therefore joined a regional project for PODS implementation.

PODS Implementation

We implemented the PODS process at a large, publicly funded academic psychiatric hospital in Toronto. In 2019–2020, this hospital had 3,320 admissions to 330 beds, with an average length of stay of 14 days. The hospital has 22 units that cover a wide range of diagnoses and treat patients as young as 14 years old.

Our staged implementation started with two units and gradually expanded to all units in the hospital. The implementation phase occurred over 3 months, is described elsewhere in detail (

7), and followed the previously published provincewide implementation plan (

7). Because this facility was the only psychiatric hospital taking part in the provincewide implementation, the standard PODS template was modified to address psychiatric illnesses and common elements of a psychiatric discharge plan, such as a crisis plan. The hospital’s overall implementation plan was developed by a central team with input from stakeholders—unit social workers and pharmacists, community partners, patients, and families—to support and enhance existing workflows. Two units with a high volume of discharges and treating patients with a range of different psychiatric diagnoses were selected for the first phase. Each unit had a local PODS implementation team consisting of a PODS champion (usually the unit’s social worker), a pharmacist, a physician, the nursing team lead, and one to three members from the central implementation team. Problems were identified in real time and solved by the local PODS implementation team, which then provided data to the central team that informed later implementations. Subsequent units were rolled into the implementation in an order that was based on the unit’s ongoing projects, training of champions, and volume of discharges.

After the PODS implementation, units received weekly feedback on a run chart that displayed their performance on PODS completion. These charts were posted in each unit and discussed as part of weekly team huddles. This project was exempt from institutional review board approval.

PODS Completion Process

At our institution, the unit social worker coordinates the discharge process and prepares a draft PODS document, incorporating input from the attending physician and the pharmacist obtained via data entry forms from the electronic medical record (EMR). The PODS template is embedded in the EMR and includes free-text boxes for details about the admission; patient education materials, including a list of reasons to seek further help or reassessment; and prepopulated fields for medication information, scheduled follow-up appointments, and clinic contact information. Unlike a traditional discharge summary, which can be completed in our EMR only at discharge, the PODS template was built to incorporate data from a series of forms (i.e., linked fields in the EMR) that could be completed at different times during a patient’s hospitalization. This flexibility allows the discharge plan to evolve over the patient’s hospitalization and permits the prompt completion of a PODS document at discharge. The expected process was that 1 day prior to discharge, a patient would meet with the attending physician (or resident), pharmacist, and social worker to review key information from the PODS document and have their questions answered. The social worker would then finalize the PODS document, provide a printed version to the patient, and go over the follow-up appointment information with the patient. The medical discharge summary would then be completed within 48 hours of discharge and sent to the patient’s primary care provider.

Results

There were 9,762 discharges between January 1, 2017, and February 29, 2020, an average of 257 discharges per month. Of these, 7,624 (78.1%) were planned (i.e., not coded as being against medical advice and not urgent transfers to a general medical hospital) and eligible for PODS completion according to the implementation plan. These 7,624 discharges were included in the analysis.

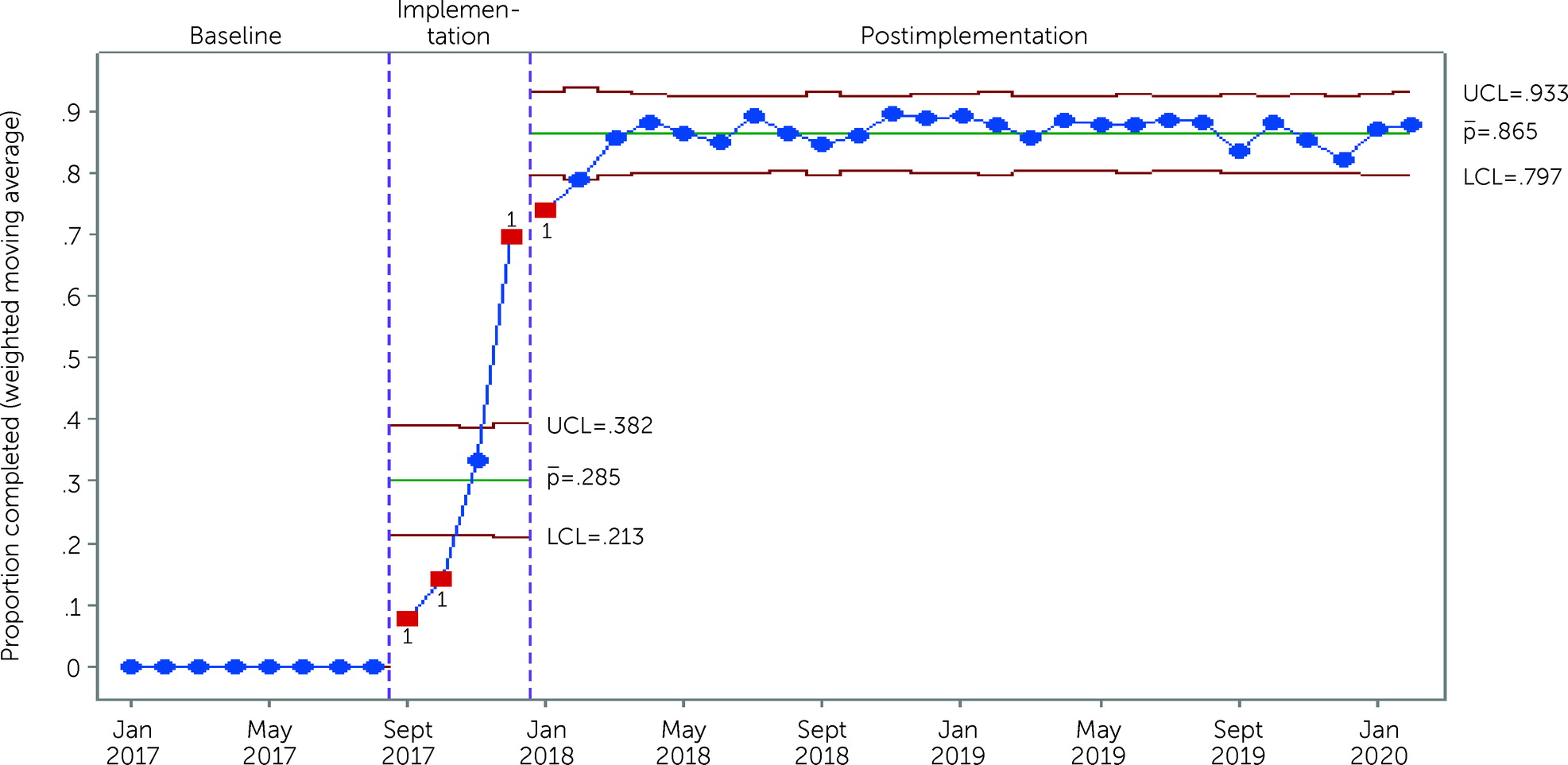

We sustained the PODS process for 2 years after implementation, as demonstrated by a PODS completion rate (weighted moving average) at discharge of 86.5% (lower control limit [LCL]=0.80, upper control limit [UCL]=0.93) over that period (

Figure 1). We also saw sustained improvement in other discharge processes, including medication reconciliation at discharge (which increased from 82.8% to 98.7%; LCL=0.96, UCL=1.00) and provision of patient-centered medication education (not done at baseline and sustained at a level of 82.9% postimplementation; LCL=0.75, UCL=0.91). We also observed improvements in the completion rate of medical discharge summaries within 48 hours of discharge, which increased from 57.1% to 74.2% (LCL=0.65, UCL=0.83) postimplementation.

With respect to clinical outcomes of importance related to patient discharge, PODS implementation coincided with the rate of postdischarge appointment attendance at our institution (scheduled to occur within 7 days of discharge) increasing from 43.2% (N=318 of 736 discharges preintervention) in the first 3 months to 51.9% (N=368 of 709 discharges postintervention) in the final 3 months. Scheduling a follow-up appointment within 7 days of discharge is a mandated quality standard in our jurisdiction, and attendance of a follow-up appointment within 30 days is a local quality metric. However, improving the 7-day appointment booking rate did not translate into an increased rate of attendance of these scheduled postdischarge appointments (or any follow-up appointment within 30 days of discharge) or into reductions in 7-day emergency department visits or 30-day hospital readmission rates. Because of limitations in data availability, we have only data related to care provided at our institution and cannot comment on health care provided by other services or facilities.

Reflections on Change

The PODS process was implemented with the goal of creating a patient-centered, standardized discharge procedure that used effective, timely communication to reduce the potential for harm that can arise during this care transition (

7). PODS implementation at our large psychiatric hospital was successful and led to significant improvements in discharge practices, including medication reconciliation, patient-centered medication education, follow-up appointment scheduling, and medical discharge summary completion. Despite these improvements, attendance at scheduled follow-up appointments and hospital readmission rates were not improved by this implementation.

Our implementation demonstrated that even with very high adoption of discharge best practices, including patient-facing discharge counseling and materials, downstream outcomes of importance did not improve (i.e., attendance at a follow-up appointment within 30 days, hospital readmission within 30 days). Earlier attention to this lack of change in our outcomes may have permitted us to modify the process and thereby improve these outcomes, a reminder of the importance of following rapid-cycle improvement methods during implementations.

Several potential reasons may explain why hospital readmission rates and follow-up appointment attendance did not improve. The lack of improvement in hospital readmission rates may represent optimally managed severe mental health conditions—that is, perhaps patients’ severity of illness makes our readmission rate of 10.9% for a specialty mental health hospital the best that can be achieved (

9). In relation to follow-up appointment attendance, the data were limited to care at our institution, and we provided follow-up appointments for 10% of the total patient cohort, although we scheduled follow-up appointments for about 50% of patients. Our ability to robustly assess health care use and follow-up was therefore limited, given that we could not track the follow-up appointments of at least 40% of patients. Further, this implementation of the PODS process was local and did not focus on engagement with community providers or outpatient clinics (even those at our own institution) in proactive scheduling of follow-up appointments, limiting the effect of the process and change in access to care. This project was part of a wider study of the implementation of the PODS process across a range of health care settings (

7). The focus was on the PODS process’s implementation, and the unique factors relevant to discharge from a mental health setting were considered but perhaps not sufficiently addressed.

Although patients receiving PODS documents were more likely to have scheduled follow-up appointments and to have received focused education regarding their follow-up plan, the rate of follow-up appointment attendance within 30 days of discharge did not improve. This result suggests that to improve 30-day follow-up rates, additional interventions after discharge may be required, such as active in-reach to inpatient units (i.e., the practice of outpatient providers visiting an inpatient unit to meet patients before discharge), appointment reminders, case management, and further patient education (

10). Subsequent improvement cycles at our institution have incorporated provision of a PODS document during precipitous discharges occurring against medical advice; postdischarge appointment reminder calls; and, more recently, a text-message reminder system. The outcomes of these interventions are pending.

Conclusions

The PODS process is feasible and sustainable and is associated with increases in best practices such as patient medication education, medication reconciliation, and communication with primary care providers. Although PODS implementation improved predischarge processes, it did not improve postdischarge outcomes, suggesting that additional postdischarge interventions may be needed to meaningfully improve outcomes in the postdischarge period.