Among people with serious mental illness and other mental health conditions, the presence of co-occurring substance use disorder complicates and adversely affects illness trajectories that can be effectively managed only if the disorder is identified (

1,

2). Accurate assessment is relatively straightforward among those who are already in treatment for and who self-report substance use, but biased self-reporting can make identification difficult among those recently engaged by treatment providers. This bias has several sources (

3). People with mental illness develop difficulties with relatively small amounts of substance use, confuse the effects of substances with mental illness, and, compared with those who use substances and who do not have mental illness, experience different consequences of use because of reduced personal resources and support. Admitting to having a substance use disorder and related problems can also lead to loss of both child custody and access to benefits such as housing, disability payments, employment, and welfare. These consequences provide ample motive for dissembling. When patients are given enough time to interact with care managers and other community teams, correct identification of substance use disorder is likely (

4–

6), but failure to identify it at initial engagement represents an opportunity cost associated with delayed treatment. In this study, we examined the potential use of self-reported personal characteristics to substitute for or augment established measures for substance use detection in a population at high risk for disability and substance use disorder.

The Supported Employment Demonstration (SED) was a study of people whose first applications for disability benefits (Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance), based on an alleged mental impairment in the past 30–60 days, were denied (

https://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/supported_employment.html) (

7). To help enrollees find employment and reduce rates of reapplication and eventual award of disability benefits, the SED randomly assigned participants to one of two treatment arms (basic or full) or a treatment-as-usual control group (N=2,960). After a 1-year enrollment period, the SED conducted follow-up of each participant for 3 years. Participants in the basic- and full-treatment arms were offered team-based care management, behavioral health care, and individual placement and support (

7), an effective, evidence-based practice that helps people with serious mental illness find employment (

8). Participants in the full-treatment arm were also offered medication management support and coordination of medical services from a nurse care coordinator (

7). Trained interviewers assessed baseline substance use disorder status in person for all enrollees by using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) and the 10-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10). These screening measures have some utility for individuals with either known substance use disorder or a recent history of treatment for mental illness (

9–

12). Participation in the SED was not predicated on meeting either of these criteria. SED participants reported a low level of substance use disorder on the AUDIT and DAST-10, a self-assessment that conflicted with early qualitative data, including clinical observations and interviews of providers with study enrollees, and a high prevalence of baseline characteristics known to be associated with substance use disorder (

13). Examples of such prevalent characteristics (

13,

14) included back pain (63%) (

15,

16), smoking (46%) (

17,

18), obesity (47%) (

19,

20), not being employed (81%) (

21,

22), homelessness (5%) (

23–

25), a history of arrest (54%) (

26), and high school or less as the highest educational level attained (49%) (

27,

28). Baseline diagnostic interviews that used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview with 1,842 SED participants indicated a high prevalence of anxiety disorders (71%) and antisocial personality disorders (46%) among these participants (

14,

29).

SED participants experienced clinical difficulties, such as those related to legal problems, family conflicts, or medical conditions related to substance use disorder, which reinforced the importance of reliable substance use disorder identification (

30). Projects like the SED that rely on baseline measures to determine substance use disorder status may not include more reliable approaches, such as the use of collateral information from friends and family (

31), urine drug screens (

6), time-line follow-back interviews (

32,

33), extensive research interviews (

34), or the collection of basic demographic, behavioral, and diagnostic characteristics associated with substance use disorder (

5). The SED enabled evaluation of this last option by providing a large sample of baseline data and a long period of follow-up during which treatment teams, including employment specialists, case managers, and clinicians, evaluated participants’ substance use (

6). The objective of this study was to examine the sensitivity and specificity of the baseline AUDIT and DAST-10 scores for identification of substance use disorder, to determine the associations of known enrollee characteristics with observed substance use disorder, and to use classification tree analysis (CTA) to demonstrate practical means of using combinations of personal characteristics to identify participants with substance use disorder.

Methods

Participants

This study assessed detection of potential substance use disorder based on combined AUDIT and DAST-10 scores and baseline characteristics in a subsample (N=1,354) of the SED cohort for whom observed substance use disorder status was known and in a subset of that group for whom the presence or absence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), antisocial personality disorder, anxiety disorder, and mood disorder diagnoses was known (N=706). We chose not to define smoking as a substance use disorder; instead we considered it an observable behavior, because smoking had the potential to indicate alcohol abuse or drug use that the AUDIT and DAST-10 may have failed to detect. Standard cutoff scores for the AUDIT and DAST-10 were used to determine sensitivity and specificity, with observed substance use disorder status as the gold standard for detection of alcohol abuse or drug use. We constructed five series of decision trees that were based on combinations of the baseline AUDIT and DAST-10 substance use disorder indicator and on baseline personal and diagnostic characteristics, and we determined the mean sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for each.

Measures

Determination of substance use disorder.

Observed and instrument-based measures of substance use disorder were expressed as indicator variables.

Observed behavior.

At the end of follow-up, SED treatment teams classified each participant in both intervention arms as having or not having a substance use disorder or as not having been observed fully enough to make a determination; these data were collected in Microsoft Excel. Not all participants in either treatment arm participated in services. Despite extensive and ongoing attempts to engage enrolled participants, many never engaged with their treatment teams (largely because of inaccurate contact information and lack of response to outreach) (

35) or declined any participation in services (

36). During discussions, treatment teams applied

DSM-V criteria (

37) on the basis of team members’ interactions with study enrollees to determine substance use disorder status. This measure (i.e., observed substance use disorder by community-based teams) constituted the gold standard for detection of substance use disorder in this study. Subsequent analyses omitted individuals whose substance use disorder status was not observed.

Instrument-based measures.

Every SED participant completed the AUDIT and DAST-10 at baseline. Meeting threshold scores of 7 for the AUDIT or 6 for the DAST-10 indicated presence of a substance use disorder.

The AUDIT is a 10-item screening test designed to detect high-risk drinking. Reliability and construct and criterion validity are acceptable. In populations with a range of alcohol use patterns, sensitivity and specificity of the AUDIT have generally ranged from 0.7 to 1.0 (

38). In standard usage, scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more harmful alcohol use and a cutoff score of 8 indicating harmful alcohol use and potential alcohol dependence (

39). Cutoff sores of 7 or 8 were identified as optimal for people with severe mental illness (

9).

The DAST-10 is a 10-item version of the original 28-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) that is scored on a scale of 0–10, with higher scores indicating more harmful drug use. It has been reported to have moderate to high validity, sensitivity, and specificity. Most studies of the psychometric properties of the DAST and DAST-10 have been conducted in populations of individuals known to use drugs or with patients with an established psychiatric history (

12). Scores of 6 and 9 represent standard cutoffs, indicating substantial and severe substance use, respectively, and lower cutoff scores optimize detection of problematic drug use among those with serious mental illness (

9–

11). The SED sample contained individuals with a range of mental illness severities.

Diagnoses.

Diagnoses of PTSD, antisocial personality disorder, anxiety disorder, and mood disorder were based on the results of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview administered by trained interviewers either in person or by telephone to 1,842 SED enrollees soon after enrollment.

Baseline characteristics.

Baseline demographic, behavioral, and general medical measures included age (<35 or ≥35 years), sex (male or female), race (White, Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, or two or more races), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), highest level of education achieved (less than high school, high school or general equivalency diploma, some college or technical school, or completed bachelor’s degree), current housing status (homeless or in a shelter, multiple apartment or house addresses, or one apartment or house address), any employment in the past 2 years (yes or no), current smoker (yes or no), any history of arrest (yes or no), obesity at baseline (yes or no), and back pain at baseline (yes or no).

Statistical Analysis

Data preparation.

This analysis used a combination of SED baseline data and observed substance use disorder status. To assess the generalizability of results to the SED sample, we compared the distribution of the chosen baseline characteristics in two groups: participants with observed substance use disorder status and participants with no observed status.

Detection of substance use disorder.

We first determined the sensitivity and specificity of the combined AUDIT and DAST-10 instruments by using the full sample of individuals whose substance use disorder status had been observed. Two multivariable logistic regressions were used to describe the associations of positive substance use disorder detection (on the basis of the combined baseline indicator) and of baseline characteristics, including or not including diagnostic data, with observed substance use disorder status. The model that included diagnostic data was restricted to the subset for whom these data were available. To account for type I error inflation associated with multiple hypothesis tests, we selected an α=0.003.

We used CTA to evaluate discrimination of substance use disorder status, with five sets of predictors to be used as potential nodes; each tree was trained and validated in the sample for which predictors were available. CTA hierarchically maximizes correct classification without assuming multivariate normal distributions and can illuminate patterns of interaction in the data and predictive values relevant to practical identification of substance use disorder (

40). We computed sensitivity and specificity with confusion matrices and reported AUCs for CTAs. Higher AUCs (those between 0.5 and 1.0) indicate that a model discriminates between outcomes increasingly well compared with pure chance. Predictor sets included the baseline substance use disorder indicator, baseline characteristics of SED enrollees, and baseline characteristics and psychiatric diagnoses. To the latter two groups, we then added the baseline substance use disorder indicator. Performance measures represent means based on 10 CTAs for each predictor set; each CTA used 70% of the sample for training and 30% for validation. We used pruning with the C4.5 algorithm (

41) to avoid overfitting the data and improve generalizability to other data sets; we limited the tree to a depth of four, binary branching, and a minimum of 20 enrollees per leaf. For purposes of illustration, we created a classification tree by using the entire sample for training and based on the four baseline characteristics most frequently utilized across 40 decision trees. Analyses were conducted in SAS, version 9.4 (

42), with proc logistic and proc hpsplit.

All procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

Treatment teams provided observed substance use disorder status for 1,354 enrollees. Although largely representative of the SED cohort, they were slightly older, had higher educational attainment, were less likely to smoke at baseline, and had higher rates of anxiety and mood disorders than those for whom observed substance use disorder status was unavailable (

Table 1).

The 2,959 and 2,946 SED enrollees who completed baseline AUDIT and DAST-10 assessments, respectively, had a computed baseline substance use disorder prevalence of 19% (N=544 of 2,922). The observed substance use disorder prevalence during follow-up was 32% (N=433 of 1,354). Assuming that observed substance use disorder status constituted a gold standard, we found that the baseline indicator detected substance use disorder with a sensitivity of 0.34, specificity of 0.88, and positive and negative predictive values of 0.57 and 0.74, respectively. The latter values represent the probabilities that positive or negative test results are correct.

Table 2 shows the results of both logistic regressions, including the ORs associated with each parameter. In the model that used only baseline characteristics as predictors (N=1,222), smoking versus nonsmoking (OR=3.32, p<0.001), having versus not having an arrest history (OR=2.28, p<0.001), and being homeless or living in a shelter versus living at a single fixed address (OR=2.83, p<0.001) were significantly associated with substance use disorder. In the model that also included baseline diagnoses (N=706), smoking versus nonsmoking (OR=2.94, p<0.001), having versus not having an arrest history (OR=2.38, p<0.001), and having versus not having a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (OR=1.87, p=0.001) were associated with substance use disorder.

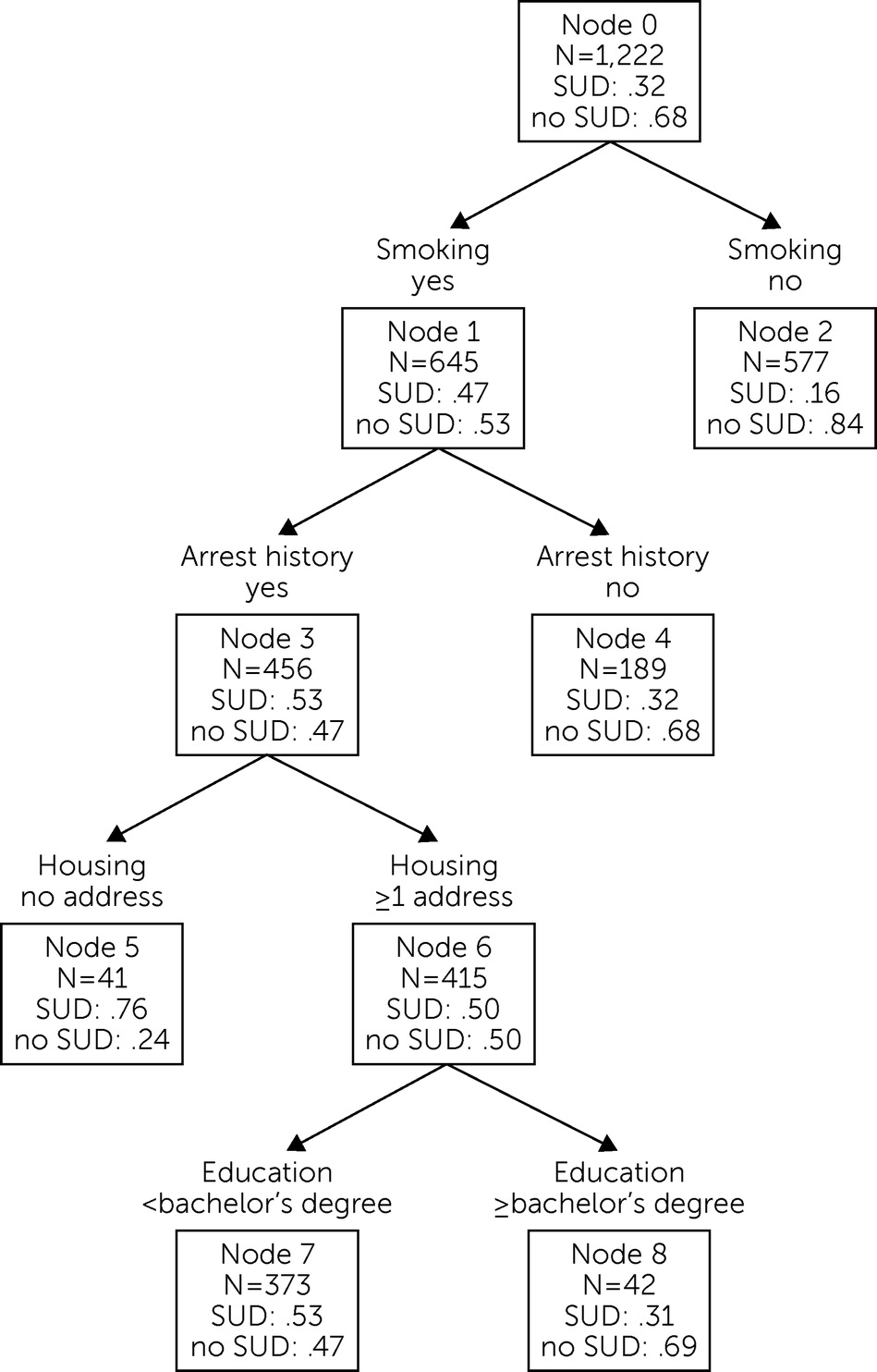

The results of the CTAs, which were based on random sample partitions and displayed a range of performance characteristics, are shown in

Table 3. The trees created by using baseline characteristics had a mean AUC of 0.71, sensitivity of 0.47, and specificity of 0.83; those that included diagnostic status had a mean AUC of 0.72, sensitivity of 0.54, and specificity of 0.81. Addition of the baseline substance use disorder indicator to these predictor groups only negligibly improved the AUC at the cost of decreased sensitivity.

Figure 1 shows the classification tree that was trained by using the entire sample and was based on the four baseline nondiagnostic characteristics most frequently selected for the prior decision trees (smoking, arrest history, education, and housing). Only 16% (N=90 of 577) of nonsmokers, compared with 47% (N=300 of 645) of smokers, and 32% (N=60 of 189) of smokers without arrest histories, compared with 53% (N=240 of 456) of smokers with arrest histories, had observed substance use disorder. Of SED enrollees who smoked, had an arrest history, and were homeless at baseline, 76% (N=31 of 41) were observed to have a substance use disorder.

Discussion

Several key points emerged from this study of the detection of substance use disorder among individuals whose first application for disability benefits because of a mental illness was denied. First, screening for substance use disorder status based on a few personal characteristics commonly known at intake was more accurate than AUDIT and DAST-10 scores. Second, combining these characteristics with the results of the AUDIT and DAST-10 instruments did not substantially improve detection of substance use disorder. Third, further work is necessary to understand the practical value of personal characteristics to screening and to combine these findings with existing techniques in order to develop a more efficient screening process.

The approach used here resembles that of a previous study of substance use among hospitalized psychiatric patients with severe mental illness, which also used hierarchical regression tree analysis to identify characteristics associated with alcohol, cocaine, or cannabis use (

5). The themes of incarceration, antisocial personality disorder, and housing identified in that study echo those identified in our SED sample, but the former study omitted other background characteristics associated with substance use disorder, including tobacco use and arrest history. Previous research has reported mixed success in using existing screening instruments to detect substance use disorder. Although some studies have indicated that measures such as the AUDIT, DAST, and DAST-10 are useful for detecting substance use among recently hospitalized psychiatric patients (

9,

11), others have concluded that these measures are generally of low value (

6). Some of this variance may be due to the sensitivity of standardized instruments to both the skill of the interviewer and the characteristics of the enrolled participants (

43). These difficulties are compounded in populations, such as that sampled for the SED, with histories of arrest and of seeking disability benefits (

3). The results of this study reinforce the inaccuracy of established measures for screening for substance use disorder applied in isolation to disability applicants with mental illness and highlight the importance of confirming test performance under challenging circumstances. Subgroup-specific prediction of substance use disorder represents an effective and easily implemented augmentation of existing practices.

Basic demographic, behavioral, and diagnostic data that correlate with substance use disorder are commonly available when clinicians initially engage patients with mental illness. The AUDIT and DAST-10 accurately screen for possible substance use disorder when responses are unbiased, a condition that appears to be consistently unmet in this population. Research is necessary to confirm whether other established instruments are subject to the same shortcoming and to explore whether recall bias can be reduced. However, in populations prone to biased recall, detection of possible substance use disorder based on specific background characteristics appears to be more accurate than the use of simple screening instruments. This finding is of crucial importance when more resource-intensive techniques are impractical. Given larger samples and the measurement and evaluation of additional personal traits, such as the characteristics of relatives (

44), subgroup-specific detection of substance use disorder could constitute a first level of screening. This screening would be of specific value in clinical environments treating populations that are prone to biased recall and lacking the resources for universal application of more rigorous procedures. The process could be implemented by individual providers (e.g., case managers) or through automated application to electronic health records. Additional methods, such as time-line follow-back interviews (

32), could then be applied selectively to individuals in high-risk subgroups. Development of tiered substance use disorder detection based on high-risk subgroup identification that guides deployment of more accurate methods would enhance the convergent validity long known to compensate for shortcomings in any one method of detection (

45).

Use of observed substance use disorder status as a gold standard was a primary limitation of this study. Evidence suggests that this information is of high accuracy, but in this study, it represented a period prevalence (i.e., the number of cases during a specified period divided by the total number of people in the population) of substance use disorder. The AUDIT and DAST-10 scores yielded an estimate of the baseline substance use disorder as a measure of point prevalence. Although the emergence of many new substance use disorders during the study was unlikely, this difference between period prevalence and point prevalence may have caused an upward bias in the relative estimated risk for substance use disorder by including substance use disorders that developed during the follow-up period. Also, the group with observed substance use disorder status was not entirely representative of the SED sample, being older, more educated, and less likely to smoke and having higher rates of anxiety and mood disorders, thereby limiting generalizability.

Conclusions

Traditional substance use disorder screening instruments are inaccurate, especially for people who are under surveillance or applying for various benefits and whose drug use may have perceived negative legal or financial consequences. Biased responses to items in tests such as the AUDIT and DAST-10 can cause underestimation of substance use disorder prevalence and lead to misdiagnosis, inaccurate treatment planning, and suboptimal care. Combining personal characteristics correlated with substance use disorder with other detection methods could increase the reliability of substance use disorder identification at the point of initial engagement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mustafa Karakus for his comments on the manuscript.