Population-based studies indicate that only half of youths in the United States who experience mental illness receive any mental health services (

1,

2). Moreover, the quality of mental health services is highly variable, with few youths receiving evidence-based care (

3), and epidemiologic surveys do not usually provide information about the quality of mental health services received. Receiving adequate treatment in childhood can reduce both current impairment and the likelihood of psychiatric problems later in life (

4,

5). Previous mental health services research has used several definitions of treatment adequacy. Minimally adequate treatment, a frequently used standard (

3), uses a prescribed set of rules to determine whether treatment is adequate for the primary mental illness (e.g., for children with depression or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], minimally adequate treatment consists of four or more visits with any mental health care provider plus medication or eight visits without medication over 1.5–3.0 years, depending on the study). Of note, only 10%–43% of children with mental illness receive minimally adequate treatment (

6–

8). Children are more likely to receive minimally adequate treatment if they have depressive disorders or have two or more comorbid mental disorders (

7). Another definition is “guideline-concordant care” (

9–

11), codified as receiving psychotherapy plus recommended medication (and no contraindicated medication) according to treatment guidelines for a particular diagnosis.

Sociodemographic variables, including socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity, appear to be important determinants of treatment adequacy. For example, youths with private insurance (vs. Medicaid) are more likely to receive adequate care (

8). Several studies that adjusted for confounders (e.g., socioeconomic status indicators) have found racial and ethnic disparities in access to adequate care. In a nationally representative sample of youths in the United States experiencing mental health impairments, Black and Hispanic youths and underinsured youths were less likely to receive adequate care compared with White and insured youths, respectively (

6). Among Medicaid-enrolled children, Black and Hispanic children were less likely than White children to receive appropriate medication, psychotherapy, or both across studies of children with ADHD or bipolar disorder (

10,

12). Regardless of definition of treatment adequacy, research consistently finds that, among youths who receive mental health care, <50% receive adequate care (

6–

8).

Although some consensus exists across methods for determining adequate care, these methods are not well suited to address other questions about quality of care. Researchers who have used minimally adequate treatment approaches have noted that these approaches do not allow for assessment of the comprehensiveness of care, comorbid conditions, or the appropriateness of different medications (

6). In this study, we used an expert consensus approach to identify adequate care that considers both appropriateness of different medications and comprehensiveness of care, given a child’s comorbid conditions. Researchers have long used expert consensus to determine diagnoses and classify treatment and other clinical characteristics (

13–

16). In this study, a child psychologist and a child psychiatrist reviewed the treatment records of children who sought outpatient mental health treatment. They independently determined whether each patient’s treatment was adequate on the basis of recently published guidelines and recommendations (a list of guidelines is available in Table S1 of the

online supplement to this article), by asking the core question, “Are the type and combination of services a child is receiving evidence based for their diagnoses?” They reviewed cases together to reach consensus when independent ratings did not match. Potential benefits of this approach are the ability to fully utilize all information available to rate treatment quality; flexibility to take into consideration comorbid conditions, age, and other clinical and treatment characteristics (e.g., recent inpatient hospitalizations); and utilization of the expert knowledge of two clinicians with complementary expertise.

We examined associations of demographic characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, and insurance status) and clinical characteristics (diagnoses and global functioning) with receipt of adequate treatment. We hypothesized that being a member of a minoritized racial or ethnic group or having a less severe clinical presentation would be associated with an increased likelihood of receiving inadequate care.

Methods

Participants

Data were from baseline assessments of the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study (

13,

17). The LAMS study prospectively followed up with a large, diverse sample of children, ages 6–12 years, at risk for bipolar disorder at enrollment. Screening and enrollment details are reported elsewhere, and we used procedures that were approved by the institutional review boards at each institution (

13). Participants were recruited during their first visit to one of nine outpatient clinics, all associated with academic health centers. Baseline interviews occurred well after the screening assessment or first clinic appointment; the mean±SD number of days between assessment and interview was 40.8±40.3 (median=30.0 days). The analytic sample included 601 children with sufficient information to assess mental health care adequacy and their demographic characteristics (97% of 621 baseline participants).

Measures

Demographic information, reported by caregivers, included the child’s age, race, ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/Latino), insurance status (Medicaid or other coverage), and caregiver income and education (high school, general equivalency diploma [GED], or some college, bachelor’s, professional, or doctoral degree). Caregivers reported their children’s race as American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, White, or biracial/multiracial or did not disclose. For analyses, race was recoded as Black/African American, White, or other race (including all other responses).

Child psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms were assessed with the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present/Lifetime, with additional questions about depressive and manic symptoms from the Washington University in St. Louis version (K-SADS-PL-W) (

18,

19). The K-SADS-PL-W is a semistructured interview assessing youths’ current and most severe past symptoms of >30 psychiatric conditions and disorders based on

DSM-IV criteria. Trained interviewers interviewed caregivers and children and used all information available to determine diagnoses.

Global functioning was assessed with the interviewer-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS); scores range from 0 to 100, indicating poor and excellent functioning, respectively (

20). All diagnoses and CGAS scores were reviewed and confirmed by a licensed clinical psychologist or child psychiatrist.

Mental health service use data were collected by using the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA), an assessment of current and lifetime use of outpatient, inpatient, and school mental health services with excellent reliability and validity (

21,

22). Caregivers reported interventions that their children received, the reasons for seeking services (e.g., “thoughts about death” or “gets in fights at school”), and the duration of services. Caregivers also reported youths’ current and lifetime medication use.

Care Ratings

Two expert clinicians (a licensed child psychologist [A.S.Y.] and a board-certified child psychiatrist [R.L.F.]) reviewed participants’ current and past psychiatric diagnoses, medications taken (medications prescribed but not taken were not considered), psychotherapy received, psychiatric inpatient admissions, number of sessions, and duration of each intervention. They independently rated children’s current pharmacologic and psychotherapy interventions as standard of care, adequate, inadequate, inappropriate, or treatment pending (see Table S2 in the online supplement for details). Raters had access to all SACA data, K-SADS-PL-W–derived diagnoses, and participant age. Other demographic variables (e.g., race, ethnicity, income, and insurance status) were masked for this review. Discordant ratings were discussed until reviewers arrived at consensus. A third tiebreaker expert was available; however, consensus was always reached. Among the demographic and clinical variables, participants with discordant ratings across the five categories (25%) differed only on bipolar diagnosis, with participants whose ratings were discussed being more likely to have bipolar disorder than those whose ratings were not discussed.

Reviewers used a “benefit of the doubt” approach: interventions were assigned the most favorable rating possible, given the available information. Treatment ratings were then collapsed into two groups: inadequate (combining inadequate, inappropriate, and treatment pending ratings) and adequate (combining adequate and standard-of-care ratings). We considered whether treatment pending fit best with the adequate or inadequate group; we determined that children whose treatment was still pending for on average >1 month after their initial clinic visit were not receiving the indicated treatment. Ultimately, whether a child was receiving the indicated treatment was our primary interest. Combining groups also helped avoid small cell sizes. Interrater reliability across the binary adequacy variable was substantial (Cohen’s κ=0.72; for further information about rater agreement, see Tables S3 and S4 in the online supplement).

After we inspected the data, analyses were limited to medication adequacy. Insufficient information was available to confidently ascertain whether psychotherapy was evidence based (caregivers often simply reported “psychotherapy” without additional information). Psychotherapy information was still used to inform medication treatment ratings where appropriate (e.g., a child with depressive disorder not otherwise specified, without evidence of it being severe, who was participating in psychotherapy would receive a medication rating of adequate). Reported medication information was typically well detailed, with specific formularies and doses reported; only five cases had insufficient information to provide a consensus psychopharmacotherapy rating.

Statistical Analyses

We used chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and t tests (for continuous variables) to examine univariate associations between sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses, and psychopharmacologic treatment adequacy. Relative risk was computed to aid in interpretability.

Logistic regression models were used to examine associations among sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses, and adequacy of current psychopharmacologic treatment. The first model included only sociodemographic characteristics (sex, race, ethnicity, age, primary caregiver education, and insurance). The second model included these same sociodemographic characteristics, dichotomous indicators for each psychiatric diagnosis, and CGAS scores. Finally, we added race × insurance status and race × caregiver education as interaction terms to the model. Standard errors in all models were estimated with cluster-robust variance estimates to account for clustering of participants by academic center of recruitment. Statistical significance was assessed at p<0.05. We conducted analyses in RStudio, version 1.2.5042; R, version 4.0.0; and SPSS.

Discussion

We examined adequate receipt of pharmacotherapy by children with a more nuanced, expert consensus method that accounted for their diagnoses and the extent to which their treatment approached guidelines established for those diagnoses. We hypothesized that, among 601 children at high risk for mood disorders, children from minoritized racial groups and those with less severe presentations (i.e., with higher CGAS scores and without bipolar disorder) would be less likely to receive adequate care.

Just above half of the children (51%) were receiving adequate pharmacotherapy. This proportion is somewhat higher than the 10%–43% estimate obtained with approaches assessing minimally adequate treatment used in earlier studies (

6–

8). Several reasons might account for this difference. In minimally adequate treatment approaches, the same rules are applied to every child’s treatment, regardless of age or comorbid conditions, whereas our consensus approach was informed by treatment guidelines and could flexibly account for variability in patient characteristics such as age, severity, and comorbid conditions. Additionally, patient characteristics might differ between our study population and those in earlier studies; previous studies often used claims data and focused on youths with Medicaid insurance. In this study, more detailed information about service use was available, and insurance type varied. Further, the children in our study all sought treatment from academic medical centers. It is possible that children in such clinics may be more likely to receive adequate care.

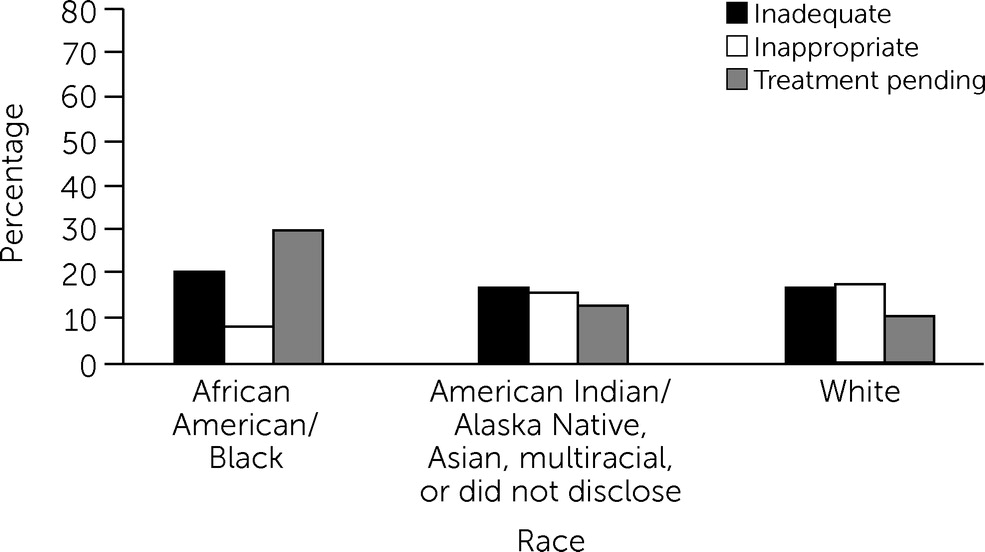

Consistent with previous research, caregiver education was significantly associated with receiving adequate care. Children whose caregivers had a bachelor’s degree or more education were more likely to receive adequate care than those whose caregivers had less than a bachelor’s degree. Also consistent with our a priori hypotheses and with previous research, Black children were less likely than White children to receive adequate care. White children and those who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, or biracial/multiracial (combined into one group because of small subgroup sizes) did not significantly differ in the likelihood of receiving adequate care. Although Black children were also more likely than children who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, or biracial/multiracial to receive inadequate or pending care, it remains unclear whether the observed racial disparity was specific to Black children because of the heterogeneity of the combined race group. This effect persisted after adjustment for other demographic and clinical characteristics; the racial disparities identified could not be explained by differences in insurance status, caregiver education, or diagnosis. It is noteworthy that many Black children were in the subgroup for treatment pending, suggesting that public health efforts that speed up the initiation of active treatment for Black youths who come to mental health clinics seeking care could decrease disparities. The racial disparities identified in this study are consistent with earlier LAMS analyses in which we identified racial disparities in treatment retention over time (

23), as well as multiple other studies finding similar disparities in access to children’s mental health services (

24–

33).

Although this study was not designed to determine causes of racial disparities, such disparities in access to health care are well established and may originate from inequitably distributed financial or logistic barriers (e.g., distance from home to clinic and availability of feasible appointment times) or systemic barriers such as provider bias and the relatively smaller number of mental health care providers practicing in areas having more people from minoritized racial groups (

34–

37). The results may also reflect possible differences in patient and family treatment preferences. Treatment preferences are frequently investigated as contributors to disparities in access to health care (

38–

40), but they often appear to explain only a small portion of disparities (

29). Taken collectively, the results highlight the need both for systemic change to reduce barriers and for providers to carefully reflect on their own biases and the long, complex history of medical harm and health disparities that may contribute to mistrust of the medical profession among minoritized groups (

41–

43).

Having an anxiety disorder (vs. no anxiety disorder) was associated with receiving inadequate care. Anxiety disorders might be unrecognized or undiagnosed by treating providers, or families may not pursue recommended treatment. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that pediatric anxiety disorders may be significantly underdiagnosed in clinical settings (

44–

46). Increased dissemination of information about evidence-based interventions for childhood anxiety to practitioners (

45), and perhaps novel dissemination strategies, are warranted.

Counter to our hypotheses, bipolar disorder was not significantly associated with receipt of adequate care. We expected that worse functioning or more severe mental illness would increase the likelihood of receiving adequate care, because previous research has indicated that youths with more severe presentations are more likely to engage in mental health care (

7,

23). However, more severe presentations may also be more challenging to manage and may require multiple interventions or interventions with more adverse effects (e.g., mood stabilizers with cardiometabolic adverse effects), leading to less adequate care.

These results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, we focused on medication adequacy because detailed information about psychotherapy was lacking. Caregivers often had difficulty recalling, or perhaps had never been told, what type of psychotherapy their children were receiving; therefore, we could not reliably rate the adequacy of the psychotherapy received. Second, ratings occurred, on average, about 1.3 months into treatment—likely enough time for many children to start medications or psychotherapy but not long enough in some cases. However, notably, receiving adequate vs. inadequate pharmacotherapy did not vary by how much time a child had been in treatment before the time point at which we rated their treatment. Third, to provide informed ratings, unmasking expert raters to diagnoses and participant age was essential, and this approach is vulnerable to subjectivity; however, each treatment rater had been practicing in their respective fields (psychiatry and clinical psychology) for ≥10 years and were clinical researchers familiar with up-to-date research on evidence-based treatment and guidelines. Further, consensus was required for the final categorization of treatment adequacy. Fourth, information regarding treatment preferences of patients and their families was not available and, therefore, was not taken into account. Finally, participants were 6- to 12-year-old children from the midwestern United States. Access to mental health care may differ by region (

47,

48); therefore, these findings may not generalize to children with other demographic characteristics.

However, we note some strengths. LAMS is a uniquely rich data set that uses reliable, valid methods to determine diagnoses across a relatively large, diverse sample. LAMS has detailed service use records that include recent psychiatric hospitalizations, duration of treatment, and number of treatment sessions attended. In these analyses, we used an expert consensus approach to assess treatment adequacy, which enabled full utilization of the rich information available to determine treatment adequacy, and to do so flexibly, taking into account patients’ comorbid conditions, age, and other clinical and treatment characteristics (e.g., recent inpatient hospitalizations). Furthermore, although we used an uncommon approach to assessing treatment adequacy, our findings are consistent with those of previous studies on disparities in access to care.