The United States is facing a critical shortage in the behavioral health workforce across a broad range of providers—including psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, counselors, therapists, case managers, social workers, and peer support specialists—who deliver mental health and substance use services. This shortage has been compounded by inequitable distribution of providers, rising burnout, and challenges with employee recruitment and retention. Workforce expansion is needed as a response to growing population health demands. Approximately one of three U.S. adults experiences a mental health or substance use condition, and behavioral health service gaps are increasing across many states (

1). High demand for behavioral health services has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been associated with higher prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms (

2) and record rates of overdose deaths and suicide attempts (

3). Despite the need for improved access to behavioral health services, one-third of those with any mental illness report unmet needs. These service gaps are even more prevalent among individuals with serious mental illness (including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other mental health conditions causing functional impairment) as well as those with substance use disorders (

4).

Access issues are compounded within the public behavioral health system, which provides services and programs to some of the country’s most vulnerable individuals—including a disproportionate share of those with serious mental illness—with limited resources (

5). The public behavioral health system is generally financed through a combination of Medicaid payments and local, state, and federal grants. The system is composed of community health clinics, school and community-based organizations, and state mental health hospitals, jails, and other entities (

6). In many ways, the public behavioral health system acts as a safety net by serving low-income populations, including people receiving Medicaid, people without insurance, and people at high risk for behavioral health problems (

7,

8). High turnover and attrition of providers are notable problems in the public behavioral health system, with an annual industry turnover average of about 30% (

9,

10). Turnover results in loss of expertise and institutional knowledge, high costs for recruitment and training of replacement providers, and care disruptions and delays for patients (

11).

Addressing workforce shortages is a high priority for state and federal policy makers. In recent years, a number of policy proposals have been developed or implemented to address behavioral health workforce shortages across states, including efforts to raise reimbursement rates for behavioral health services (

12,

13), increase support for telehealth (

14,

15), expand loan forgiveness and recruitment programs for trainees (

16,

17), and establish stable funding mechanisms for behavioral health programs through the certified community behavioral health clinics (CCBHCs) overseen by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (

18). The success of these policies relies on an understanding of the factors contributing to behavioral health provider turnover and attrition in public behavioral health systems. Although a body of literature has examined factors contributing to provider burnout across various training stages (

19) and settings (

20), including acute care hospitals (

21) and primary care (

22,

23), little recent work has examined which factors contribute to shortages of behavioral health providers in public health systems.

The well-being and stability of the clinical workforce, particularly in the public behavioral health system, are crucial to the U.S. health system. In this study, we conducted qualitative interviews with providers, administrators, and policy experts with knowledge of the public behavioral health system in Oregon, which (like many states) is facing a workforce shortage and high rates of unmet behavioral health needs (

24). Our objective was to assess factors contributing to workforce turnover and attrition in Oregon’s public behavioral health system, with a focus on challenges in the clinical work environment. This study was designed to expand the limited qualitative data on this topic and shed light on the perspectives of behavioral health professionals with firsthand experience of working in the field.

Results

We conducted 24 qualitative interviews with behavioral health providers, program administrators and leaders, state association or agency administrators, and policy experts with knowledge of the public behavioral health system in Oregon (

Table 1). Most of the interviewees (N=19, 79%) were current frontline behavioral health providers or had clinical experience but had shifted to an administrative role within the behavioral health field. Findings from the interviews are summarized and presented visually in

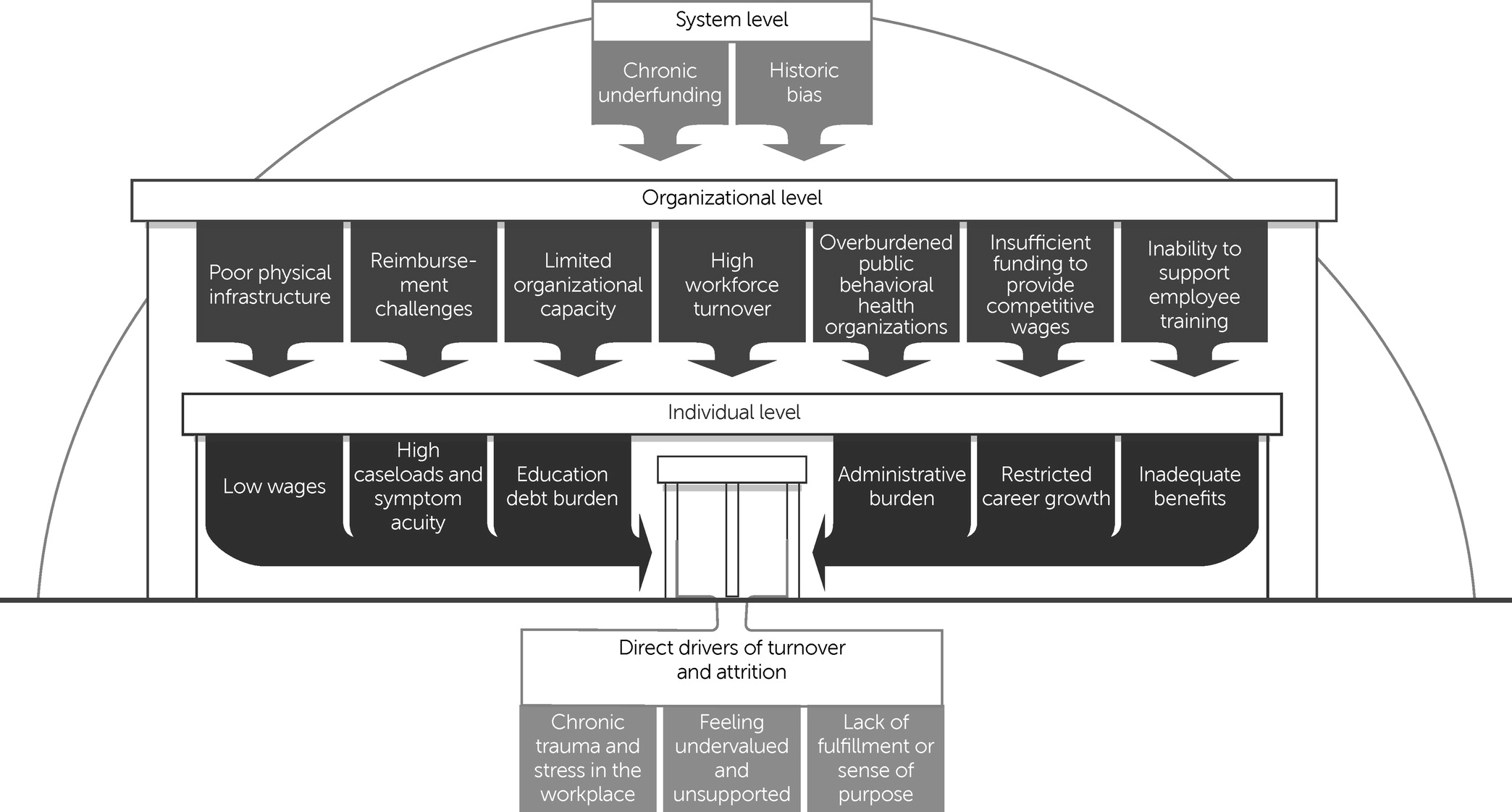

Figure 1. Interviewees identified various interconnected factors affecting their workplace experience that we designated across three levels: system, organizational, and individual. System-level factors included overarching government policies and societal views on behavioral health; organizational-level factors were those related to infrastructure, administration, and support within an organization or workplace; and individual-level factors encompassed day-to-day experiences affecting an individual’s financial, emotional, or physical well-being. These factors coalesced into direct drivers of turnover and attrition, which we identified as chronic trauma and stress in the workplace, feeling undervalued and unsupported, and lack of fulfillment or sense of purpose. Five major themes emerged from the analysis of the various factors. Example quotations for the five themes are provided in

Table 2, and a glossary of terms is available in the

online supplement to this article.

Theme 1: Low Wages

Participants generally agreed that the public behavioral health field requires high educational investment but offers low financial return, with several participants attributing low wages to historical reliance on provider goodwill. Across the state, several participants reported that wages for entry-level behavioral health positions were on par with or lower than those at fast-food restaurants in their locales. In addition, insufficient supervisory and leadership roles limited opportunities for promotion and wage progression. As a result, participants reported more difficulty alleviating debt burdens compared with peers in medical professions with higher entry-level wages.

A frequent observation was that public behavioral health organizations could not compete, in wages or benefits, with national telehealth companies or large hospitals at any level of staffing. Five participants reported leaving their employer or turning down otherwise desired positions because of low wages or inadequate benefits (e.g., lack of affordable health insurance). Eight participants reported that in recent years, their organizations had not offered cost-of-living increases, differential pay for language skills or other additional service provision, or supplemental benefits (e.g., professional development funds).

Participants felt that low reimbursement rates for services directly limited the salaries and benefits offered by their employers. Several participants believed that lower reimbursement rates—particularly compared with those for general medical services—were a remnant of historical bias toward the behavioral health field, which resulted in persistent stigma and financial undervaluing of behavioral health services. A state association administrator said, “The behavioral health system has been underfunded for decades. You can’t pay people more than [an organization] gets paid to do the work.” Participants felt that low salaries actively pushed employees out of the public behavioral health system or out of behavioral health completely, contributing to workforce shortages.

Theme 2: Documentation Burden

Many participants shared that documentation and reporting burdens often exceeded what they could feasibly complete in a standard work week and felt that this burden significantly contributed to provider-level stress, burnout, and turnover in the public behavioral health system. A director of a community mental health organization reflected, “[A] leading reason . . . people leave the public behavioral health system is administrative burden. It seems meaningless. It doesn’t make them happy.” Participants felt that documentation burden directly reduced time available for patient care. For example, a program manager at an outpatient mental health clinic described a near-continuous communication loop with insurers to receive prior authorizations for basic services and to get claims approved; some claims were ultimately denied because of formatting issues. Funding streams were often fragmented between different entities with incompatible documentation requirements, demanding hours of staff time to receive full reimbursement for services.

Many participants perceived the public behavioral health system as held to a higher standard of reporting and accountability compared with the general medical health system. Several participants believed that policy makers and state leaders expected evidence of financial cost savings or documentation of treatment efficacy in behavioral health, which exceeded standards in general medical health. For example, to receive full reimbursement, providers were often required to conduct an assessment, write a treatment plan, and make a diagnosis before providing any services to a potential client. Other providers struggled to meet the changing reporting metrics required to maintain the CCBHC or evidence-based program designation and associated funding. Nonintegrated health information technology systems made it difficult for staff to track clients across settings and locations and to locate the historical documents necessary for these assessments and reports.

Theme 3: Poor Administrative and Physical Infrastructure

Much frustration was voiced about inadequate operational support in the public behavioral health system, including poor administrative and physical infrastructure. Regarding administrative support, participants reported that their organizations often had insufficient and inconsistent funding available to hire human resources, administrative, and supervisory staff. Many participants described long delays in hiring and onboarding new employees, which forced them to maintain large caseloads for months at a time.

Multiple participants reported that their small facilities operated in a state of disrepair, which lowered morale and forced staff to operate in outdated buildings that the clinics had outgrown. Organizations with few financial resources often used temporary state or community grants to provide basic services or to hire staff, which limited physical infrastructure investment. A state agency administrator reflected,

How are we paying for the infrastructure to create environments where people feel good about where they work? How do we ensure that they have data systems that support their work? All of that gets in the way of retention and recruitment. Who wants to come to work in an environment that isn’t very clean?

Many participants noted a general lack of facilities, especially in rural areas, to treat a spectrum of behavioral health needs.

Participants commented that fragmented, capitated funding streams for behavioral health services left little room for operational flexibility, which necessitated a choice between providing services, increasing wages, or maintaining infrastructure and did not align with the aims of delivering integrated, evidence-based care. Thirteen participants reported pervasive coding and billing limitations and inefficiencies, including considerable limitations regarding types of reimbursable services and provider billing eligibility. For example, a peer services coordinator noted that only five Medicaid codes were available for peer providers to use in billing and that these codes did not reflect the workers’ scope of services or cover the cost of their positions. State and organization-imposed limits on the types and number of services that unlicensed providers could submit for reimbursement created frustration and stress among workers. Complex billing rules also existed for clients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders.

Theme 4: Lack of Career Development Opportunities

Several participants noted that minimal organizational support, burdensome training requirements, and an ill-defined career ladder contributed to their perception of insufficient career development opportunities. Participants described substantial variation in organizational policies for paid time off or financial assistance for job-related training. Independent of official policies, some participants felt unable to participate in job-related training because of inadequate staffing, large caseloads, and loss of potential billable hours for the organization. A few participants shared that training rarely fit their schedules, was an out-of-pocket cost, or was not offered in their native language. Three participants reported that they were ineligible for many loan repayment programs or other financial support for training because they were part of the unlicensed workforce. Most participants felt that support for efficient training and licensure pathways had not been prioritized at the federal or state system level.

Many participants felt that career advancement opportunities were unclear or nonexistent; specifically, these participants felt that public behavioral health jobs did not have defined career paths with established supervisory or leadership positions. Others described inadequate mentorship from senior providers or behavioral health leaders as a result of the competing burden of daily workloads and lack of financial incentives for mentoring, both of which deprioritized professional development for junior employees. These factors contributed to a sense of disillusionment, with a few participants viewing public behavioral health as an unsustainable career choice in the medium and long term.

Theme 5: Chronically Traumatic Work Environment

Consistently large caseloads, patients with acute symptoms, and a general feeling of insufficient organizational support created a high-stress daily work environment for many participants. These challenges, along with ongoing secondary traumatic stress from caring for people exposed to trauma, were felt by most to directly drive stress and turnover. A child and adolescent psychiatrist said,

Burnout, it’s like a boulder gaining steam. As you have staff attrition and challenges recruiting, the few therapists [who] remain have a higher caseload, perhaps with greater production expectations to make up for that loss of the other providers. That’s almost like a death spiral for the organization from a burnout perspective—how do we stop the bleeding?

In addition to larger caseloads, participants commented on a general rise in patients’ symptom acuity. Multiple participants observed that new graduates who entered the workforce often were not prepared for the level of patients’ symptom severity or complexity in their caseloads and quickly became overwhelmed. The rapid turnover of new providers created additional stressors for remaining providers, who often had to absorb more clients. Providers at CMHPs described having large caseloads of patients with complex symptoms who required services for long periods of time, which they felt was due in part to lack of bed and space availability at the inpatient level of care.

Many participants reported that organizational leaders did not adequately recognize or compensate for the chronic workplace trauma the providers experienced as a result of large caseloads and patients’ high symptom acuity. For example, several participants described challenges in requesting time off and advocating for culturally relevant care or appropriate services for their patients. Certain job duties, such as supervising interns or translating documentation, were routinely uncompensated. Behavioral health providers in understaffed rural areas reported performing more than one job within their organization or working at a level of responsibility above that for which they had been hired. Most participants felt that the taxing work environment disincentivized long-term retention, especially when other settings, such as telehealth or private practice, could offer lower patient symptom acuity, higher wages, and a more flexible work environment.

Discussion

The public behavioral health system serves as a safety net for individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders, many of whom have low incomes (

30–

32). Entities financed in part or in full by public funds (e.g., county behavioral health sites, CCBHCs, FQHCs, and jails) provide essential emergency services, clinical outpatient and inpatient services, as well as rehabilitation and community support. In recent years, demand for behavioral health services at entities primarily supported by public funds has increased, and employee turnover and workforce shortages have accelerated (

33,

34). In interviews with public behavioral health providers, administrators, and policy experts in Oregon, we identified five key themes—low wages, high documentation burden, poor infrastructure, lack of career development opportunities, and a chronically traumatic work environment—that influenced turnover and attrition of the public behavioral health workforce across provider types, work settings, and geographic regions. The persistence of these challenges, which likely have worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic began (

35), has important implications for the long-term stability of this essential workforce.

Although we focused on a single state, findings specific to Oregon’s behavioral health workforce challenges are potentially generalizable to other contexts (

33). As in other states, Oregon’s public behavioral health system is heavily reliant on the Medicaid program, although health system financing, organization, and delivery differ from those of other state Medicaid programs. Although behavioral health workforce shortages have local and regional footprints, they constitute a national crisis with similar contours. Nearly every U.S. state is facing projected shortages of psychiatrists, psychologists, and other behavioral health providers—all caused by similar systemic issues (

36). Thus, the experiences of Oregon’s frontline behavioral health workers add context for policy discussions.

Our findings suggested that multiple interacting factors contribute to job dissatisfaction for the behavioral health workforce. Some of these factors have been documented, such as low reimbursement rates for behavioral health services (

37). In response, more than half of all states are implementing rate hikes or planning to raise reimbursement rates during the next 2 years (

38). However, our interviews highlighted that other factors—for example, clinical and regulatory burden, chronic stress, and lack of professional development opportunities—also appeared to be important. Many of these factors are recognized predictors of burnout. Although there is a robust body of literature on protective strategies to combat burnout (

39–

41) (e.g., addressing work satisfaction, organizational respect, employer care, and work-life integration) (

42), these strategies were infrequently cited by our interviewees. As such, reimbursement rate hikes are necessary, but likely insufficient, tools for improving workforce capacity, and commensurate attention is needed to address other factors.

Our findings suggested a need for organizational approaches to support workforce capacity and individual job satisfaction in a public behavioral health system. Potentially beneficial strategies may include streamlining hiring processes, providing paid time off to pursue continuing education and professional development training, creating supervisory roles that are compensated for time and effort, and encouraging organizational leaders to consistently recognize both the work that behavioral health providers perform and the chronic trauma that they face in their daily work.

Ultimately, organizational approaches, including positive leadership and workplace support, rely on adequate funding. Much current policy attention and funding at the federal level are directed toward bolstering the behavioral health workforce to meet public health demands. For example, the Consolidated Appropriations Act (

43), passed in December 2022, authorized new provisions to address behavioral health workforce shortages, including new psychiatry residency positions, new funds that can be used toward workforce initiatives for peer support providers, and expanded loan repayment programs for behavioral health professionals.

Similar efforts are being made at the state level. During the 2021–2023 biennium, the Oregon State Legislature appropriated $1.35 billion to support large-scale improvements to the state’s behavioral health system (

44). The OHA, which administers Medicaid and helps support public behavioral health services in the state, has been tasked with allocating these funds to strengthen infrastructure and to increase access to services. Planned funding includes grants to the state psychiatric hospital to convert temporary positions into permanent jobs, add staff, and offer wage increases (

45,

46). Moreover, grants for behavioral health organizations are intended to be used for increasing staff compensation and implementing policies to improve workforce retention and recruitment (

47). Many other states, including Virginia and North Carolina, are engaging in their own efforts to address their behavioral health workforce crises through expanded funding (

28). These efforts are crucial and should be implemented in conjunction with approaches that address the three direct drivers of turnover and attrition identified by our interviewees.

This study had several limitations. The study sample was small and was restricted to a single state, limiting generalizability of the findings. Although efforts were made to ensure representation across a variety of interviewee characteristics, women were overrepresented at high levels of organizational leadership, and participants from Oregon’s southwestern region were underrepresented. We did not systematically collect data on age or sexual orientation from our participants. In addition, this was a cross-sectional study that assessed participants’ experiences at a time when much of the funding appropriated by the Oregon State Legislature in the 2021–2023 biennium had not yet been distributed. Allocation of this additional funding to public behavioral health organizations has the potential to alter the findings of our study.