The COVID-19 pandemic has elevated rates of mental distress in the United States (

1). Fear of infection or of losing loved ones, imposed social distance from friends and family, and increased financial burdens have resulted in high rates of anxiety and depression (

2–

4). The mental health impacts of COVID-19 include fears of infection, work burnout, prolonged grief, and clinical symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and acute posttraumatic stress (

5). Symptom severity varies across groups and differs by age, gender, race-ethnicity, and occupation (

6).

Essential workers—that is, those in occupations deemed indispensable for daily community life and whose jobs usually require direct interpersonal contact—have been particularly affected by pandemic-related mental health conditions (

7). Despite laboring in diverse industries (e.g., health care, food service, transport, or construction) and varying widely in perceived social status (

8), these workers have greater daily COVID-19 exposure risk than nonessential workers (

7). Therefore, anxiety and depression symptoms among essential workers have increased since the pandemic began, especially as a result of fear of contracting COVID-19 or of infecting a loved one (

7,

9–

11). However, research documenting the prepandemic mental health of essential workers has studied only subsets of essential workers, namely health care workers, first responders, and police. For example, several studies have focused on the impact of stress, grief, and burnout on health care workers’ mental health, especially among more junior providers and those exposed to patient death (

12–

14). Research on first responders and law enforcement personnel revealed significant job-related stressors before the pandemic (

15). A recent review (

16) of mental health effects on nonessential health care workers during six pandemics (2000–2020) found 32 studies documenting increases in depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health issues among these workers.

In the decade before COVID-19, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the United States had already been slowly but significantly increasing among adults, especially young adults. The prevalence of past-year depression increased between 2005 and 2015, especially among younger people (ages 12–17 and 18–25 years) (

17). COVID-19 has accelerated these trends: studies have shown drastically increased levels of depression specifically among adolescents (45%) and 18- to 25-year-olds (37%) (

18,

19). Among young U.S. adults, COVID-19–era prevalence estimates are 43% for anxiety and 40% for depression, more than double the rates for older adults (

20).

Gender and race-ethnicity also influence mental health outcomes (

21). Several COVID-19 studies have found that women and transgender and nonbinary people were more likely to develop depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during the pandemic (

21–

25). Moreover, women contribute a higher percentage of the health care, culinary, and retail workforce industries adversely affected by the pandemic (

26). Other studies (

27,

28) have shown that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black people are more likely than non-Hispanic White people to experience COVID-19–related symptoms of mental disorders. However, no study to date has addressed the association of demographic variables with mental health outcomes among essential workers during COVID-19.

Finally, vaccination status may also be associated with mental health outcomes, although pertinent research is sparse. One Dutch study found that low COVID-19 vaccination rates were associated with chronic psychiatric diagnoses, including self-reported depression and anxiety (

29). Similarly, in a sample of European and Asian neurosurgeons (N=534), those who were vaccinated reported a lower rate of depression (

30).

In this study, we sought to understand the longitudinal trajectory of clinical symptoms in a sample of adult essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data on anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were collected online at four time points between August and December 2021. We hypothesized that we would find high rates of clinical symptoms among essential workers, with minimal changes over time; greater symptom severity among women than men and among younger than older adults; and lower rates of clinical symptoms among those with COVID-19 vaccination than among unvaccinated individuals.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited through Prolific, an online crowdsourcing tool frequently used in psychiatric research (

31). Prolific constantly screens the platform population to ensure response consistency in demographic and other characteristics (e.g., occupation) (

32). It facilitates longitudinal studies by creating anonymous respondent IDs. To enhance participant verification and data quality, we excluded participants who repeated the assessment more than once and added a timer to ensure that respondents had properly read the instructions. We excluded respondents who failed attention-verification questions (e.g., “please mark the fourth answer”).

Participants were English-speaking, U.S.-residing essential workers ages 18–80 years who replied to a mental health study request. Essential worker was defined as follows: as health care workers, including nurses, physicians, mental health professionals, health care administrators, and emergency medical technicians, and as workers in indispensable occupations such as manufacturing, food industry, construction, transportation, hospitality, and emergency services. We recruited essential workers who commuted daily during the pandemic. Participants received $3 compensation at each of the four time points, for a total of up to $12. The New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB protocol 8128).

The resulting nonprobability sample may not have been statistically representative of U.S. essential workers. Nonetheless, the large and demographically diverse sample allowed for comparisons between respondent subgroups and within subjects across time, providing insights into broader population trends.

Procedure

Before study entry and at each time point, participants reviewed an informed consent form and directions to complete study procedures via

Qualtrics.com, a secure online data collection platform. Demographic information, clinical symptoms, and COVID-19–related characteristics were first assessed in August 2021. Follow-up assessments occurred 14, 30, and 90 days after the initial assessment, with data collection completed by December 28, 2021.

Instruments

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 (GAD-7) instrument assesses the presence of seven generalized anxiety symptoms during the past 2 weeks, each rated on a scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”), with an overall score range of 0–21 (

33). Higher scores indicate greater self-reported anxiety: a GAD-7 total score of 5–9 indicates mild anxiety; 10–14, moderate anxiety; and 15–21, severe anxiety. Previous studies have reported high sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%) of the GAD-7 screen for a cutoff score of 10 (

33). In this study, the baseline Cronbach’s α (indicating internal validity for the GAD-7 items) was 0.92.

The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), a screening instrument based on the

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression, assesses depressive symptoms during the past 2 weeks (

34). Response options range from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”), yielding an overall range of 0–27. A total PHQ-9 score of 5–9 indicates mild depression; 10–14, moderate depression; 15–19, moderate to severe depression; and 20–27, severe depression. Previous studies have shown high sensitivity (88%) and specificity (85%) of the PHQ-9 for a cutoff score of 10 (

35). In this study, the baseline Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5) is a five-item yes-or-no self-report instrument that identifies probable PTSD (

36). It reflects

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD; three positive items constitute the screening threshold for probably PTSD. The PC-PTSD has good reliability and operating characteristics compared with a PTSD diagnosis based on clinician interview (

37). To focus on COVID-19–related events, we adjusted PC-PTSD-5 items for the pandemic (e.g., “In the past month, have you felt guilty or unable to stop blaming yourself or others for COVID-19–related events?”) In this study, the baseline Cronbach’s α was 0.67.

Data Analysis

Sociodemographic, clinical, and COVID-19–related characteristics were summarized by using frequencies and proportions. To analyze mean scores on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 instruments over time, longitudinal mixed-effect models were used with a random intercept to account for between-subject variances, a random effect of time point, and missing data with an unstructured covariance structure. All analyses included effects of time (baseline and 14, 30, and 90 days), age group (18–22, 23–30, 31–40, and ≥41 years), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American or Black, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Native American or Pacific Islander, and non-Hispanic other or prefer not to answer), gender (male; female; and transgender, other, or prefer not to answer). To test for sociodemographic differences (age, gender, race-ethnicity, and occupation) and other COVID-19–related factors, the model included an additional interaction effect of moderator and time point. For models with significant interactions, contrasts were performed to examine whether clinical symptoms changed differentially by moderator between baseline and 90 days. To examine differences in GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores by vaccination status, baseline vaccination status (received or not) was included in the main-effects model.

Attrition occurred at follow-ups. Pearson chi-square and t tests were used to examine differences between follow-up survey completers and noncompleters. Participants’ age and race-ethnicity differed significantly between 90-day completers and noncompleters; however, the mixed-effects model used all available data, not just those of completers, remaining unbiased under the missing-at-random assumption. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4, and all statistical tests were two-sided, using α<0.05.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Essential workers (N=4,136) completed the baseline evaluation after we had excluded 310 (7%) individuals who had failed validity tests. Of the 4,136 participants, 3,346 (81%) completed the 14-day assessment, 2,995 (72%) the 30-day assessment, and 2,545 (62%) the 90-day assessment. Mean±SD participant age was 27.7±9.3 years (range 18–73). Most respondents were women (69%).

Table 1 presents age, race-ethnicity, gender, and occupation data. Sociodemographic characteristics differed significantly between 90-day completers (N=2,545) and non-completers (N=1,591) for age (26.1±7.7 vs. 28.7±10.0 years), female gender (68% vs. 71%), and race-ethnicity (White 69% vs. 67%; Black 6% vs. 12%) but not in clinical symptom severity.

Figure 1 illustrates participants’ geographic distribution.

COVID-19–Related Characteristics and Clinical Symptoms

Table 2 presents COVID-19–related characteristics and baseline clinical symptoms. Of the 4,136 participating essential workers, 78% (N=3,208 and 2,608) reported anxiety, depression, or PTSD symptoms at baseline and day 14, respectively, and 74% (N=2,208 and 1,884) reported these symptoms at days 30 and 90, respectively. Rates of symptom endorsement did not change significantly over time. On the GAD-7 screen, 69% exceeded the mild threshold (GAD-7 scores 5–21), and 37% exceeded the moderate threshold (GAD-7 scores 10–21) at baseline; 71% (N=2,361) and 37% (N=1,242), respectively, exceeded these two thresholds on day 14; 65% (N=1,951) and 31% (N=923), respectively, exceeded these thresholds on day 30; and 66% (N=1,678) and 32% (N=824), respectively, exceeded these thresholds on day 90. For depressive symptoms, 66% reached the mild threshold (PHQ-9 scores 5–27), and 39% exceeded the moderate threshold (PHQ-9 scores 10–27) at baseline; 63% (N=2,123) and 35% (N=1,183), respectively, exceeded these two thresholds on day 14; 64% (N=1,909) and 34% (N=1,032), respectively, exceeded these thresholds on day 30; and 65% (N=1,644) and 37% (N=953), respectively, exceeded these thresholds on day 90. Overall, 27% of the respondents reported symptoms suggesting probable PTSD (PC-PTSD score ≥3) at baseline; 30% (N=1,004), 26% (N=780), and 20% (N=514) reported such symptoms on days 14, 30, and 90, respectively.

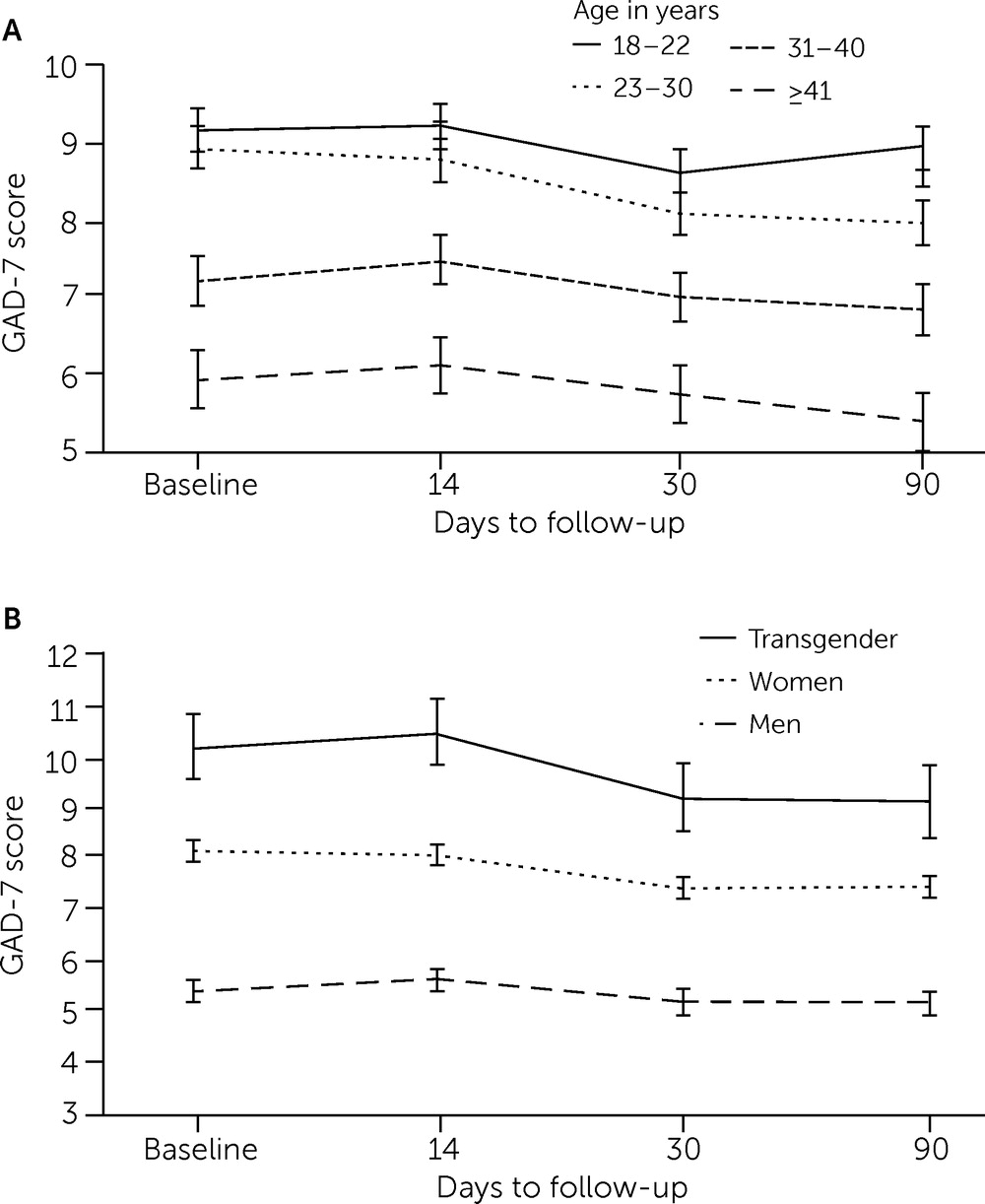

Both age (F=2.87, df=9 and 8,884, p=0.002) and gender (F=2.18, df=6 and 8,887, p=0.042) significantly moderated GAD-7 scores over time after adjustment for race-ethnicity.

Figure 2 presents the adjusted mean GAD-7 scores over time by age and gender. At every time point, adjusted mean GAD-7 scores were consistently inversely related to age group: the scores were highest among the youngest age group (ages 18–22, range 8.8–9.4), followed by the 23–30 age group (range 8.0–9.0) and the 31–40 age group (range 6.9–7.3), and were lowest among the oldest age group (≥41; range 5.5–6.2). Compared with baseline scores, 90-day GAD-7 scores significantly decreased in the 23–30 (t=−7.11, df=8,884, p<0.001) and ≥41 (t=−2.30, df=8,884, p=0.02) age groups but remained stable in the other age groups. These changes reached statistical significance but did not appear to be clinically significant.

For gender, at every time point, adjusted mean GAD-7 scores were consistently highest among transgender respondents (range 9.2–10.5), followed by women (range 7.4–8.1), and were lowest among men (range 5.3–5.7). Compared with baseline, the decrease in GAD-7 scores at 90 days among women was statistically significant by −0.70 points (t=−6.95, df=8,887, p<0.001) but, as with age, appeared to be clinically insignificant.

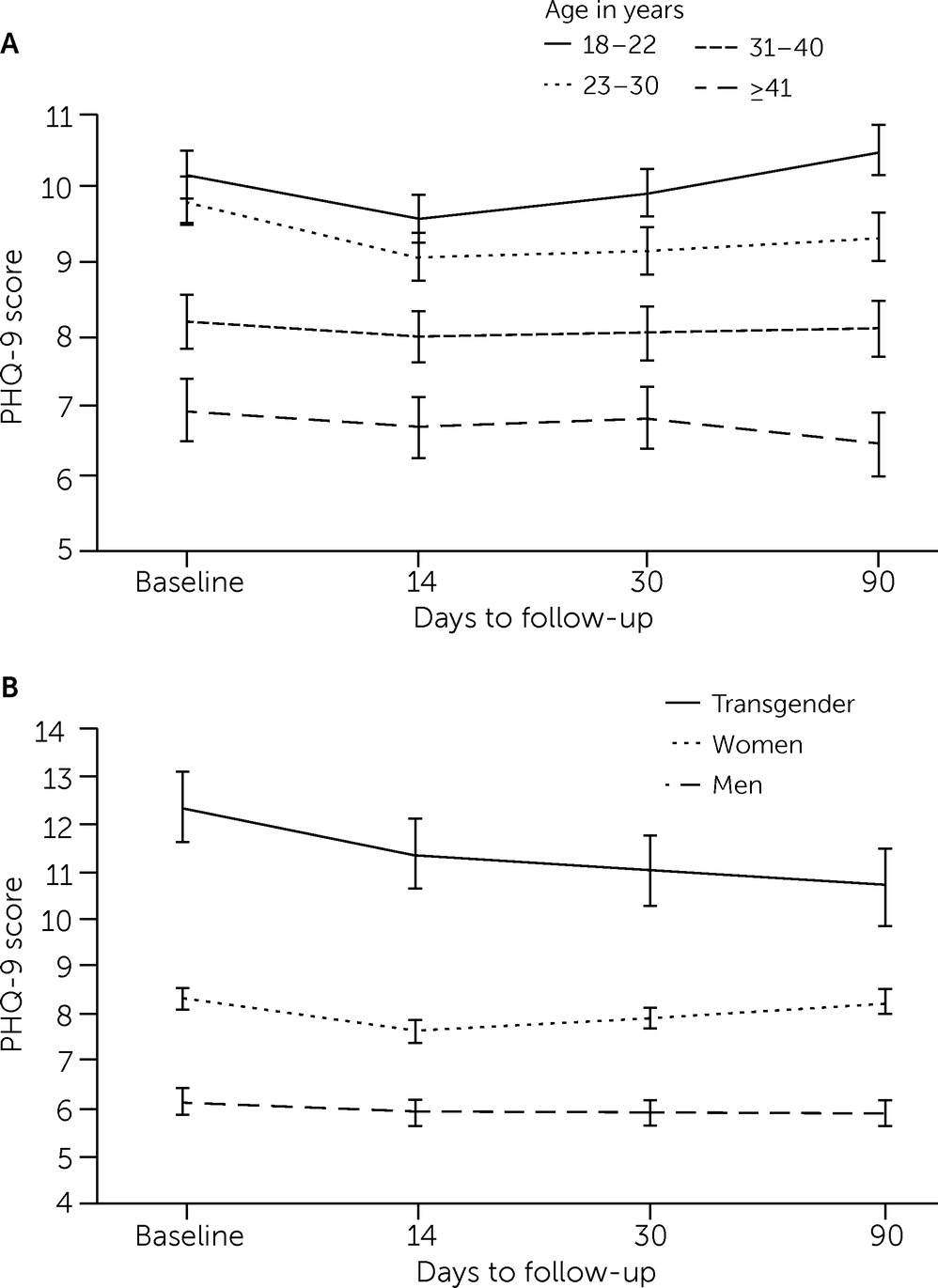

Similarly, both age (F=3.81, df=9 and 8,884, p<0.001) and gender (F=3.45, df=6 and 8,887, p=0.002) significantly moderated depressive symptoms over time, with adjustment for race-ethnicity.

Figure 3 presents adjusted mean PHQ-9 scores over time by age and gender. At each time point, adjusted mean PHQ-9 scores were consistently highest among the youngest (18–22; range 8.8–9.4) and lowest among the oldest (≥41; range 5.5–6.2) respondents. Depressive symptom scores were significantly lower at 90 days compared with baseline only for participants ages ≥41 years, which does not appear to be clinically significant. For gender, at every time point, adjusted mean PHQ-9 scores were consistently highest among transgender respondents (range 10.5–11.1) and lowest among men (range 6.5–6.7). We found no significant association between symptom level and racial-ethnic group, occupation, or geographical region.

COVID-19 vaccination status was statistically significantly associated with mental health symptoms. Baseline vaccination status significantly moderated GAD-7 scores (F=4.98, df=3 and 8,808, p=0.002) over time, with adjustment for age, gender, and race-ethnicity. At 90 days, GAD-7 scores were 0.50 points higher (t=2.03, df=8,808, p=0.04) among vaccinated participants (mean=7.5, 95% CI=7.0–8.0) than among nonvaccinated participants (mean=6.7, 95% CI=6.1–7.4). For depressive symptoms, adjusted PHQ-9 scores were 0.63 points higher (F=10.47, df=18 and 811, p=0.001) among vaccinated participants (mean=7.7, 95% CI=7.2–8.2) than among nonvaccinated participants (mean=7.1, 95% CI=6.5–7.7).

Discussion

Our study assessed essential workers’ self-reported anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms over 90 days in the latter half of 2021. As hypothesized, we found above-threshold clinical symptoms among >70% of the participants, with higher symptom rates among female than male, transgender than cisgender, and younger than older adult participants. Contradicting our hypothesis, COVID-19 vaccination was associated with slightly higher rates of clinical symptoms compared with nonvaccinated status. Clinical symptom levels remained stable over time in the absence of significant pandemic-related health developments (e.g., no new COVID-19 vaccine). We note that to our knowledge and although the United States ranks first in number of COVID-19–related infections and deaths, this is the first study to report on a longitudinal course of mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic across a wide range of essential workers.

Between 74% and 78% of the participants reported anxiety, depression, or PTSD symptoms across the four study time points. Research on COVID-19–related psychological outcomes among essential workers in the general population is scant. Although we cannot compare our sample with population-based representative samples, other Web-based opportunity samples have shown similarly high symptom rates in specific occupations. A survey of 5,077 U.K. residents showed reduced well-being and greater psychological distress among construction, manufacturing, food and retail, and transport sector employees than among individuals working from home (

38). A study from China showed that non–patient-facing essential employees reported a high rate of probable depression of 50%, as assessed with the PHQ-9 (

39). Among 637 Italian workers, those in public health emergency roles (e.g., police and emergency personnel) self-reported more anxiety symptoms and fear than did Italian students (

40).

Our results support previous findings of greater depression and anxiety symptoms among young adults (

18–

20). Several explanations may account for these increases. First, young adults endorsed increased stress levels during the pandemic resulting from events such as job loss or reduced hours, financial strains, and separation from loved ones (

18). Second, transition-age youths may be especially vulnerable to mental health problems during the developmental period of identity consolidation, characterized by powerful needs for a sense of competence, social acceptance, and autonomy (

41). Third, young adults report greater COVID-19–related loneliness, distress, and worry, which predict psychiatric symptoms (

42).

Our findings emphasize the need for early detection and treatment of mental health difficulties among young essential workers. Such workers are often reluctant to seek mental health care, which increases the need for interventions to facilitate greater openness to treatment seeking. Among barriers to care, treatment-related stigma is a significant obstacle; some essential workers perceive receiving treatment as a weakness or failure to meet social or personal expectations (

43,

44). Long after the pandemic eventually fades, psychiatric sequelae among these young essential workers may persist, leaving them vulnerable and needing assistance (

45–

47). Stigma and treatment avoidance are not the only obstacles to care. Limited availability of services and inadequate insurance also pose barriers to care. Research needs to examine the need for policy changes and how to increase the likelihood of care seeking among essential workers.

Our findings of higher symptomatology among female than male essential workers corroborate results from the literature (

21–

24). Although the subsample of transgender or other participants was relatively small (N=79), they reported the highest PHQ-9 (range 10.5–11.1) and GAD-7 (range 9.2–10.5) scores of any group. Usually marginalized, transgender individuals face unprecedented difficulties with mental health and social well-being and challenges accessing mental health care (

25). These disparities are worsened by policies based on binary gender norms that can impede transgender individuals’ access to mental health care and increase the risk for psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic (

48). Surprisingly, we found no significant association between racial-ethnic group and symptomatology. Future studies should explore psychiatric symptoms, ways to increase access to care, and policy changes for in-need groups.

COVID-19 vaccines were freely available to essential workers beginning in early 2021, months before this study took place. Accordingly, 80% of the participants reported receiving at least one COVID-19 vaccination at baseline, increasing to 86% at day 90 (data not shown). The most frequent reasons for declining a COVID-19 vaccine were “I don’t trust its efficacy” (50%), “Because of the side effects” (47%), and “It is not needed” (20%) (data not shown). A U.S. study on hesitancy regarding a future vaccine, with sampling designed to reflect national census data, reported similar explanations, that is, unknown efficacy and adverse effects (63%) (

49). A recent review identified the following vaccine hesitancy factors: perceived risk, concerns about safety and effectiveness, lack of doctors’ recommendations, and history of influenza vaccination (

50).

We found that receiving a COVID-19 vaccination was associated with slightly higher rates of clinical symptoms of anxiety and depression than not having received a vaccination. It is possible that people with higher baseline anxiety levels tend to have higher vaccine acceptance. We cannot, however, draw conclusions about causality given the cross-sectional nature of the assessment. Our interpretation of this result concurs with some of the current literature. For example, a German study of 1,779 adults found that COVID-19–related anxiety and health-related fears were associated with higher vaccine acceptance (

51), as did a French study of 2,047 health care workers (

52). Our data replicate existing literature, extending findings to essential workers in the United States.

Our study had several limitations. First, its findings are limited to a convenience sample of Prolific participants, who may not fully represent the population of essential workers. This restriction precludes comparison of our prevalence findings with those of the general population. The material used to recruit participants mentioned mental health, which may have encouraged enrollment of people with psychological difficulties. Ethnoracially, our sample fairly closely resembled the 2020 U.S. census distribution: 13% versus 16% Hispanic or Latino, 68% versus 72% non-Hispanic White, and 8% versus 13% non-Hispanic African American or Black in this study versus in the United States, respectively. However, at the 90-day follow-up assessment, non-Hispanic African American or Black participation had decreased to 7%. Second, we did not collect data on socioeconomic status or education level, which both are associated with mental health outcomes. Third, clinical assessments based on self-report questionnaires rather than formal diagnostic interview are subject to over- or underreporting (

53). The PC-PTSD had borderline internal reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.67). Last, the cross-sectional nature of the data precluded addressing causality, and absence of pre–COVID-19 information limited comparison with the prepandemic era.

Conclusions

More than 70% of essential workers surveyed in this study consistently reported symptoms of generalized anxiety, depression, or PTSD over the course of 3 months in late 2021. Younger adult, female, transgender, and COVID-19–vaccinated participants reported greater distress. The overwhelming, unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the mental health care needs of essential workers, especially in these subgroups. Employers and administrators should support and proactively encourage employees to access care when needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the essential workers who participated in this study.