The opioid crisis continues to have a tremendous impact on the U.S. health care system (

1). Overdose deaths have reached unprecedented levels (

2), and complications of injection drug use have contributed to increases in emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations (

3). Opioid use disorder is associated with myriad adverse health consequences (

4) and accounts for the highest health care utilization among substance use disorders (

5–

7). In total, the excess health care utilization associated with opioid use disorder costs the U.S. health care system approximately $90 billion each year (

8).

Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is an effective intervention to improve health outcomes and address the health care burden of the opioid crisis (

9). The evidence-based pharmacotherapies buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX)—when taken as directed—protect against overdose, promote abstinence from opioids, and increase treatment retention among individuals with opioid use disorder (

9). MOUD has been associated with reduced health care expenditures, driven largely by reductions in ED visits and hospitalizations, even after accounting for the cost of opioid use disorder treatments (

10,

11).

To date, most studies evaluating health care utilization among those receiving MOUD, compared with those who are not, have been retrospective analyses of claims-based data (

12–

23) or data retrieved from medical records (

24–

29). Studies relying on claims and medical records data have been limited in their ability to fully account for medication adherence (because although data such as medication prescription and fill dates are captured, they lack evidence of whether individuals are taking their medication as prescribed) (

30) and to control for detailed individual and social determinants of health, including educational attainment, insurance status, access to care, clinical severity, and composite measures (e.g., employment, social support, psychiatric complications), that may confound the relationship between MOUD, health outcomes, and health care utilization.

Among the published studies reviewed for this project, we found only one that included data derived from a randomized controlled trial. Ling et al. (

31) demonstrated that those receiving monthly extended-release buprenorphine (XR-BUP) had fewer ED visits and hospital days compared with those receiving placebo, although no significant differences were found in the amount of inpatient addiction treatment or outpatient care. The Ling et al. study, however, examined only one type of MOUD, did not measure nonstudy MOUD, and did not control for confounding factors. These variables are important because patients may move in and out of treatment depending on their preferences and clinical stability; focusing only on random assignment (XR-BUP or placebo) does not account for participants who drop out of the study, receive MOUD through community programs, or access health care services for other reasons (e.g., psychiatric or general medical problems).

The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN) trial comparing XR-NTX with buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NX) for opioid treatment (X:BOT) (

32) afforded the opportunity to conduct a rigorous, longitudinal, multivariable analysis of the association between health care utilization and MOUD among a sample of individuals seeking treatment for opioid use disorder. The present study used a novel measure of MOUD adherence—a combination of directly observed and detailed self-report data collected via timeline followback and time-anchoring methods (

33,

34). We used an ordinal, time-varying measure of adherence to MOUD (including both study and nonstudy MOUD) as well as person-level characteristics that may influence health care utilization over time. We hypothesized that participants with greater adherence to MOUD during a given time frame would be less likely to use inpatient addiction treatment and acute care during that time and would be more likely to engage in outpatient care. An enhanced understanding of the relationship between increased adherence to MOUD and changes in specific types of health care utilization could better inform how decision makers allocate resources to fight the opioid crisis.

Methods

X:BOT Trial Overview

The present study was a secondary analysis of data from the X:BOT trial. The study design and rationale (

33,

35), primary outcome analysis (

32), cost-effectiveness analysis (

34), and key secondary outcomes analyses (

36,

37) have been published. In brief, X:BOT was a 24-week randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of treatment with XR-NTX (N=283) versus sublingual BUP-NX (N=287) for relapse prevention among patients with opioid use disorder. Participants were recruited among patients admitted to eight U.S. inpatient addiction treatment programs and were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, met

DSM-5 criteria for opioid use disorder, had used nonprescribed opioids during the past 30 days (heroin or prescription opioids), and were willing to accept treatment with either XR-NTX or BUP-NX. All sites obtained institutional review board approval, and all participants provided written informed consent. Study visits occurred weekly across the 24-week intervention period and at weeks 28 and 36 (follow-up period).

Measures

Baseline demographic and clinical covariates.

Demographic characteristics reported at baseline included age, sex, race, ethnicity, health insurance, educational attainment, and marital status. Clinical variables included participants’ baseline health-related quality of life (on a scale of 0, death, to 1, perfect health), measured via the three-level version of the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-3L) instrument (

38); composite measures from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) comprising baseline ratings of medical, employment, alcohol, drug, legal, family or social, and psychiatric problems (on a scale of 0, no problems, to 1, severe problems) (

39); random assignment (XR-NTX or BUP-NX); and mean days of utilization for the respective health care resource category during the 30 days prior to random assignment. Inpatient addiction treatment during the 30 days before random assignment was for episodes other than the index admission.

Nonstudy health care utilization.

The outcome of interest was nonstudy health care utilization among all X:BOT participants across the 36 weeks of the study (

32–

34). Health care utilization was self-reported, with time-anchoring methodology via the Nonstudy Medical and Other Services (NMOS) form (

34), at each monthly study visit. Four resource categories were defined: inpatient addiction treatment, which included days spent in a hospital or residential setting for detoxification or MOUD initiation; outpatient addiction treatment, which included days spent in outpatient substance use disorder treatment and substance use disorder therapy visits; acute care, which included ED visits and days spent in a hospital for general medical or psychiatric reasons; and other outpatient care, which included outpatient general medical and mental health therapy visits.

Adherence to MOUD.

The main predictor variable was adherence to MOUD, which included any MOUD prescribed through the study or outside the study. Study medications (XR-NTX and BUP-NX) were provided for up to 24 weeks (intervention period) or until relapse. XR-NTX was administered by monthly injection; each injection was assumed to provide 30 days of medication adherence, as consistent with human laboratory studies (

40). For participants randomly assigned to receive BUP-NX, adherence was monitored via timeline followback (

33). Use of nonstudy MOUD (e.g., XR-NTX and BUP-NX provided by community treatment programs, oral naltrexone, sublingual buprenorphine, or methadone) was assessed by using time-anchoring methodology via the NMOS form (

34).

Adherence to MOUD was defined as the percentage of days on which a participant took an MOUD (PDM). PDM was calculated as the number of days on which an MOUD was taken during a 30-day period divided by 30. Although optimal clinical cutoff points for adherence to MOUD have not been established, previous studies (

20,

22,

41) have distinguished adherence from nonadherence by using a PDM threshold of ≥80%. Adherence to MOUD was thus operationalized as an ordinal variable, and participants were grouped into three levels of adherence: low (PDM <20%), medium (PDM ≥20% but <80%), or high (PDM ≥80%). Rather than evaluating adherence as a binary variable (i.e., adherent [PDM ≥80%] vs. nonadherent), we used these three levels to evaluate gradations of adherence.

Data Analysis

The unit of analysis for our primary variables of interest (i.e., adherence to MOUD and health care utilization) was the person-month. This unit aligned with the primary data collection points of the trial and reduced missing-data bias by using all available data for each participant up to the point of censoring or study end (

42). An ordinal, time-varying measure of MOUD adherence was used. This time-varying approach allowed us to examine the relationship between MOUD adherence in a given month and health care utilization in the same month, resulting in a more precise measure of adherence.

All analyses were conducted in accordance with guidelines for conducting evaluations of health care utilization and other economic measures alongside clinical trials (

42). Individual multivariable regression analyses were estimated within a generalized linear model (GLM) framework for each of the four resource categories studied. Standard errors were clustered at the participant level to control for intragroup correlation from repeated measures over time. In each instance, the overdispersion of zeros dictated that a zero-inflated two-part model would be appropriate. Such models could be used to evaluate the extent to which MOUD adherence influenced health care utilization through the effects of adherence on the probability of an individual using a specific resource and on the quantity of the resource consumed, if any.

A probit regression analysis was used in the first part of the model to estimate the probability of an individual using a given resource in a particular month. The second part of the model used a GLM regression analysis to evaluate the quantity of services used, conditional on having used any. The aforementioned guidelines were also followed to determine the most appropriate mean and variance function for the GLM portion of each model (

42). Inverse probability weighting was used to address potential bias caused by missing data (

43), following methods used as part of the X:BOT trial’s economic evaluation under the assumption of data missing at random (

32,

34).

Both parts of each model included the measures of MOUD adherence (as delineated above), site and study-month fixed effects, and interaction terms of adherence and month. Control variables in each stage of the model included age, sex, race, health insurance, educational attainment, marital status, baseline health-related quality of life, baseline ASI composite measures, random assignment (study medication received), and a participant’s use of the resource of interest during the 30 days prior to random assignment.

The predicted mean number of utilization days was calculated for each resource and time point, by adherence category, via the statistical method of recycled predictions. The predicted mean values were then summed over 24 weeks (intervention period) and 36 weeks (intervention plus follow-up). Differences in the predicted mean utilization estimates were tested by using standard errors derived from the recommended nonparametric bootstrap method (

42).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Sample characteristics.

Baseline descriptive characteristics are shown in

Table 1. Among the 570 participants randomly assigned to receive a study medication, on average, participants were 34 years old, and most were male (70%), were White (74%), and had completed high school or its equivalent (78%).

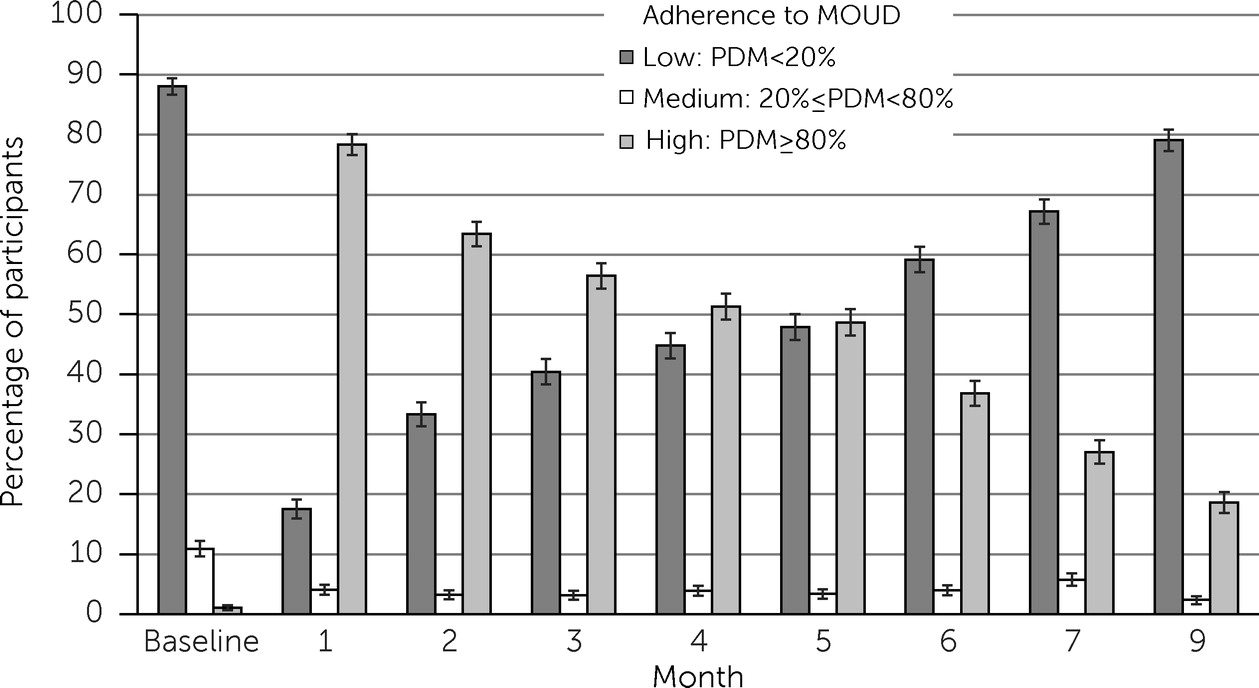

Distribution of adherence to MOUD.

Figure 1 shows the monthly distribution of participants by adherence category from baseline (i.e., prior to random assignment) through the end of the week 36 follow-up. Of note, the adherence categories were time varying, (i.e., participants may have been categorized differently each month). As can be seen, the proportion of participants with high adherence diminished over time, consistent with the documented problem of deterioration of MOUD adherence.

Predictive Analysis

All variables and results derived from the probit models and GLMs are shown in the online supplement to this article. The results for the main predictor variables (the measures of MOUD adherence) are presented below.

Inpatient addiction treatment.

Participants with high adherence to MOUD were less likely to use inpatient addiction treatment (p<0.001) than were those with low adherence. However, among participants who used any inpatient addiction treatment, those with high adherence used significantly more inpatient addiction treatment days (p=0.032) than did those with low adherence.

Outpatient addiction treatment.

Participants with medium and high (vs. low) adherence to MOUD were more likely to use outpatient addiction treatment (p=0.003 and p=0.045, respectively). Among participants who used any outpatient addiction treatment, only those with medium adherence, compared with low adherence, used significantly more outpatient addiction treatment days (p=0.010).

Acute care.

Participants with high adherence to MOUD, compared with low adherence, were less likely to use an ED or hospital for psychiatric or general medical reasons (p<0.001). Among participants who used any acute care services, neither those with high adherence nor those with medium adherence used significantly fewer acute care days compared with those with low adherence.

Other outpatient care.

Participants with high adherence (vs. low) to MOUD were more likely to use other outpatient care (p=0.042). Among participants who engaged in any other outpatient care, those with medium adherence, compared with low adherence, used significantly fewer other outpatient care days (p<0.001).

Predicted mean health care utilization days.

Table 2 shows the predicted mean number of utilization days, derived from the GLM portion of each model, for each resource category, by adherence group, across the 36-week assessment period. Participants with high adherence to MOUD, compared with low adherence, used 17.87 fewer inpatient addiction treatment days (p<0.001), 3.32 fewer acute care days (p<0.001), 1.28 more outpatient addiction treatment days (p<0.001), and 10.45 more other outpatient care days (p=0.034) across the 36-week assessment. Participants with medium adherence to MOUD, compared with low adherence, used 8.90 more outpatient addiction treatment days (p=0.045) over the 36-week assessment.

Discussion

We evaluated the extent to which increased adherence to MOUD was associated with changes in health care utilization patterns among participants in the national X:BOT trial (

32). Across 36 weeks, participants with high adherence to MOUD, compared with those with low adherence, were significantly less likely to use inpatient addiction treatment and acute care and were significantly more likely to engage in outpatient care. Although direct comparisons are difficult because of differences in data sources and adherence definitions, our findings supported those of previous research (

16,

18) indicating that greater MOUD adherence is associated with lower rates of inpatient addiction treatment and acute care and with increases in outpatient service utilization.

This study overcame key limitations of previous research. In contrast to previous studies that evaluated health care utilization among those receiving MOUD, our study included any MOUD (i.e., study and nonstudy MOUD: XR-NTX, BUP-NX, oral naltrexone, sublingual buprenorphine, and methadone) taken by the participants, a rigorous measure of adherence, and a repeated-measures analysis with time-dependent adherence, all of which increased our ability to draw conclusions from the data. Differences between our findings and those of previous studies may be explained by differences in the methodological approaches: we categorized MOUD adherence into three levels, and we evaluated how the levels of adherence influenced the probability of using a service, as well as the quantity used. Furthermore, we were able to control for a wide range of factors that could potentially confound the relationship between MOUD adherence and service utilization.

Whereas participants in the group with high adherence to MOUD used more outpatient care days than those with low adherence, participants in the medium adherence group had the highest number of outpatient addiction treatment days. The latter finding should be approached with caution, however, because there were relatively few cases in this category (e.g., 21 cases at week 24 and 12 cases at week 36). Medium adherence to medication may reflect greater engagement with nonmedication psychosocial treatment. Alternatively, medium adherence may reflect a type of poor adherence associated with worse clinical outcomes and greater risk for morbidity (

9,

44–

46), which may in turn result in higher health care utilization and more frequent office visits. The small proportion of participants categorized as having medium adherence may indicate that adherence is mainly a binary phenomenon—adherent or not—although the occurrence of some cases in the medium category is of interest and deserves further study, perhaps reflecting patients who move on and off buprenorphine as needed or a nonlinear relationship between adherence and health care utilization.

Strengths of this study included the use of data derived from a longitudinal, multisite trial, which allowed for more precise and comprehensive measures of MOUD adherence and health care utilization (i.e., the primary variables of interest) over time, as well as the extensive list of individual and social determinants of health, measured at the participant level. Additional strengths included the relatively large community-based sample and the use of a repeated-measures analysis with time-dependent adherence. This study was limited in that, as a secondary analysis, it was not part of the parent study’s a priori design. In addition, data about adherence and service utilization were self-reported and thus were subject to social desirability and recall bias; however, this limitation was addressed with frequent (i.e., weekly to monthly) administration of validated assessments (

47–

49). Without plasma samples of naltrexone concentrations, we were not able to account for the variability in medication coverage among individuals receiving XR-NTX in our analysis.

Nonadherence and deterioration of adherence over time, as observed in this study (

Figure 1), are documented problems, and interventions are needed to improve adherence to medication-based treatment. Examining predictors of adherence may be helpful in designing interventions. Understanding whether negative prognostic indicators (e.g., severe psychiatric or general medical problems) and indicators of socioeconomic status (e.g., educational attainment, employment) predict adherence to MOUD, and whether MOUD type and dosage are associated with adherence, would be valuable. Finally, exploring the associations between different levels of adherence and other clinical outcomes (e.g., opioid use, craving) and economic outcomes (e.g., hours worked, income) should be a priority for future research.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this was the first study to use data from a randomized controlled trial to evaluate health care utilization among individuals with opioid use disorder by PDM. This novel methodological approach allowed us to examine the extent to which MOUD adherence affected the use of specific health care resources over time. Our results reinforced the view that greater MOUD adherence is associated with reduced usage of high-cost inpatient addiction treatment and acute care services and increased utilization of outpatient care. Causation cannot be inferred from these data, but the data suggested that interventions that increase MOUD uptake and adherence can reduce health care costs. Because high-risk patients (e.g., those with high disease burden, complex care needs) are more likely to receive acute care and inpatient services (

50), our results suggested that increased MOUD adherence likely results in achievement of greater clinical stability and recovery capital over time. However, even with efficacious opioid use disorder pharmacotherapies, adherence continues to be a clinical challenge, highlighting the need not only for enhanced access to MOUD but also for interventions that improve adherence.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the participants, the sites, and the staff involved in this study, including the leadership of the Greater New York Node of the NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN) and the CTN Data and Statistics Center.