Psychiatric advance directives (PADs) are instruments that allow users of mental health services to state their preferences regarding future mental health care. PADs are used to increase mental health service users’ autonomy and engagement in care and to ensure that the care provided, especially in times of crisis, is aligned with their preferences (

1). We have previously identified several important steps that facilitate PAD completion: engaging peer support workers or nonpsychiatrist clinicians, educating service providers and users to manage negative attitudes toward PADs, and creating a clear process for establishing electronic PADs linked to service users’ clinical files (

2). A limitation of this research is lack of consideration of cultural factors that may influence the creation of and the specific directives included in PADs; this limitation is also apparent in the wider literature. Brown (

3) reviewed five studies on mental health advance directives published between 1999 and 2009 and noted that although participants’ ethnicity was reported in each study, none of the studies evaluated the influence of culture on PAD creation or use. The only study reporting on the influence of culture on PADs was from a cohort of 85 Latinos in Florida (

4), indicating strong support for family involvement in directive completion and for the use of bilingual documents.

Current New Zealand health policy reflects the five principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi) recognized by the New Zealand Ministry of Health (

5). A Māori model of PADs that supports

rangatiratanga (self-determination), active protection of Māori health, options for health care that reflect Māori models, and partnership would directly address four of these principles and thereby help to achieve equity, the fifth principle of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Our earlier PAD research (

6) recruited relatively few Māori participants and did not explore ways of developing a Māori-centered approach to creating a culturally relevant PAD instrument. To address this gap, we collected data to assist with developing a Māori PAD model.

We aimed to prioritize Māori perspectives on PADs in our research, recognizing that Māori disproportionately experience coercive mental health care (

7), have an inequitable voice in decision making about responses to their mental distress, or have limited opportunities to seek mental health support that incorporates

kaupapa (Māori knowledge and values) (

8). Māori face increased risk for involuntary detention when clinically assessed under New Zealand’s mental health legislation. The current legislation does not require clinicians to take the culture of a mental health service user into account when conducting assessments. Clinicians are encouraged to seek involvement of

whānau (family), but ultimately such involvement is discretionary (

9). Without a cultural assessment, no opportunity is available to explore the cultural safety, strengths, and resources that might reduce distress and provide support options for the service user. Approximately half of Māori who receive a diagnosis of a severe mental illness are diagnosed as having schizophrenia, and Māori are 3.2 times more likely to be placed into involuntary care under the Mental Health Act than non-Māori (

9).

Study Design

Our research was a prospective Māori-centered qualitative study to record the lived experience of

tāngata whāiora (people seeking wellness),

whānau (extended family), and Māori clinicians. We used this information to create a

whānau ora (family health) model of PADs and to ensure a pathway for its culturally safe implementation. The University of Otago Human Ethics Committee approved this study (H20/084), and participants provided written informed consent. We collected data at seven

hui (meetings).

Hui were conducted after a

tikanga (Māori traditional customs and practice) that guided engagement with

whānau and participants. The

hui were led by a respected

kaumatua (male elder) and

kuia (female elder) who were engaged in mental health services. In all but one meeting, where one person was not Māori, all participants were Māori. Participants either had lived experience with mental health services as

tāngata whāiora or

whānau or were

iwi (tribal) representatives,

whānau ora navigators, or Māori clinical staff. Audiotapes were transcribed for thematic analysis by using the six-stage model outlined by Braun and Clarke (

10). Independent of this, two Māori researchers (J.P., D.T.) compiled the information they had gathered during the

hui to create a conceptual model of a Māori PAD for

tāngata whenua (Māori people), which they called

pou herenga (literally translating to “mooring place”). The themes from the

hui are reflected in

pou herenga, and this information provides a foundation for a Māori process to create a culturally specific

tikanga-informed Māori pathway for a PAD.

In total, 38 people (29 women and nine men) participated in the seven

hui. The thematic analysis identified several concepts that the

hui participants thought were relevant to informing how best to create a pathway for

tāngata whāiora and their

whānau to navigate mental health services. One of the dominant themes that emerged from the work was that although the current PAD instrument was a good tool that could be valuable for young Māori who lack cultural connections, it would not be appropriate to simply place a Māori lens over the existing PAD instrument to create a tool for use by Māori who do have extensive cultural connections, because such an approach would lack any Māori cultural considerations.

So where’s the Māori in this framework? Because we’re still jumping through the pakeha’s [White European’s] hoop to make a Māori thing. No matter where we’re going, . . . and I understand what you’re trying to do. And I understand this [the advance directive] and it’s a good concept, like everybody’s saying. But why do we still have to justify ourselves being Māori to a pakeha system? (male Māori clinical staff)

Common to all the hui was the insistence that whānau be included in decision making and in the creation of PADs, regardless of what is required by the current New Zealand Health and Disability Commissioners Code of Rights. The Māori concepts of whakawhānaungatanga (establishing and building relationships) and manaakitanga (the process of showing respect, generosity, and care for others) are key to understanding the importance of including whānau in the decision-making process regarding care for tāngata whāiora. These concepts also include an understanding of one’s whakapapa (genealogy).

Participants acknowledged that not all Māori have traditional cultural skills and that those who understand

taonga tuku iho (treasures of heritage) are in high demand, but participants also indicated that all mental health service providers have an obligation to understand the importance of correct acknowledgments and to respect language and pronunciation, especially of people’s names.

And you refuse to say my name correctly, as opposed to trying and getting it wrong. And then there’s the other option of not even trying and calling [me] something else. That’s an immediate turnoff. Right? (female Māori peer support worker)

The

hui participants were quite clear about what they perceived to be some of the major barriers to Māori receiving culturally appropriate and inclusive care from existing mental health services. They communicated that having access to alternative therapies such as

rongoa (traditional Māori healing systems) was important.

When we look at rongoa Māori, we look much more broadly. We look at it in the way of karakia [incantations], of mihi whakatau [welcoming], all those processes there . . . [are facilitating] whānau involvement. Because that’s what does heal us, as Māori. (male Māori clinical staff)

Some participants claimed that whānau were using their own resources when standard clinical approaches did not work. They shared their impression that systemic shortcomings and lack of Māori leadership in mainstream and traditional Māori services meant that services were fragmented and not responsive to Māori needs. They expressed their strong feeling that the current service not only was inadequate but also could be counterproductive, because it induced wairua puke (the feeling that everything is erratic or out of control). Participants also indicated that “PADs” is not a good term for advance directives instruments, because in Māori, the term suggests movement, whereas what tāngata whāiora need is kia tau (stillness) and the ability to center themselves.

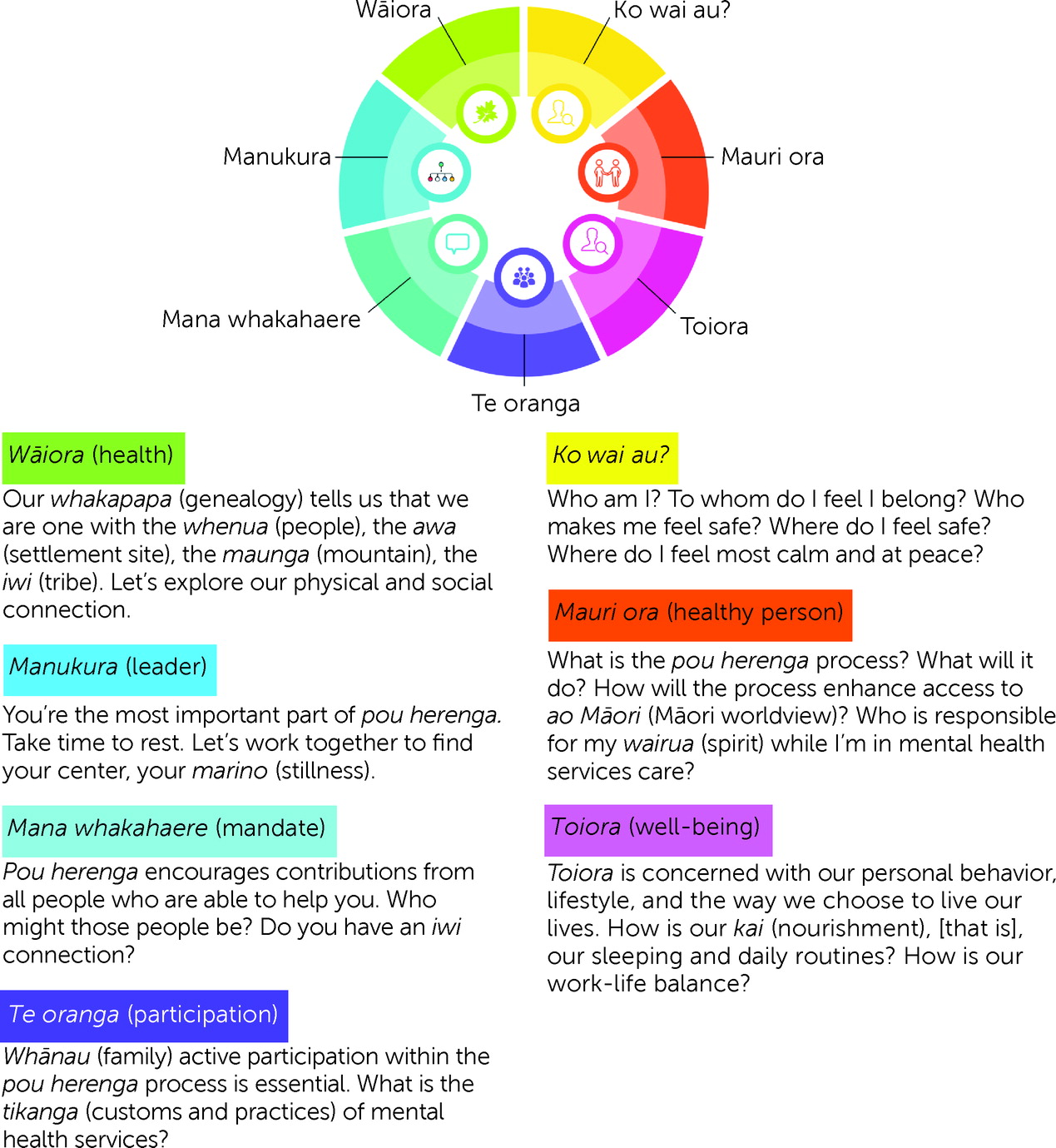

Pou herenga refers to the Māori tradition of a person landing someplace new; fixing and securing their

waka (canoe); and taking the appropriate time to rest, reflect, and replenish themselves before continuing their journey. Unlike a PAD, which identifies actions to take and thereby highlights movement and the journey being traveled,

pou herenga focuses on the importance of stopping and reassessing all aspects of one’s life journey. Centering, or finding calm, plays an integral role in the

pou herenga process. Taking stock of individual and

whānau wants and needs is essential to ensure that the time spent at

pou herenga is healing, productive, and culturally safe. The seven domains of

pou herenga (shown in

Figure 1) are broad, encompassing the themes identified in the thematic analysis. They are designed to elicit a conversation with

tāngata whāiora and

whānau, but most important is

manaakitanga when

tāngata whāiora and

whānau arrive, which creates an opportunity to discover the mental health service user’s will and preferences within a wider context.

Discussion

The main finding from this research was that Māori mental health service users are profoundly influenced by cultural issues when creating and implementing PADs, which contrasts with our earlier findings from research with a predominantly European cohort of mental health service users and clinicians, who emphasized the individual rather than the collective (

2). A broader research question, which has not yet been explored, is how cultural considerations might influence other populations’ attitudes about creating PADs.

The Māori perspective on health focuses on holistic health and well-being and on understanding individuals in the context of their culture. This perspective maps the space within which the concept of well-being can be understood and described in terms of links between physical and social environments, a community’s intergenerational potential, and connections with the land and resources. Recognizing whakapapa as inherent to Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview) ensures a culturally informed approach and is a key determinant of Māori health. Despite having areas of commonality, Māori health promotion is not simply a targeted form of generic health promotion that adapts standard practices to the preferences of Māori but is about building from Te Ao Māori. The starting point is a Māori worldview in which Māori beliefs, values, preferences, and needs are inherent. This view acknowledges that identity and cultural integrity are fundamental to good health for Māori.

Common to all hui was the insistence that whānau be included in decision making and in the creation of PADs, regardless of the requirements codified by New Zealand legislation. Under the current Western paradigm, the primary decision maker regarding the contents of a PAD is the individual patient. In contrast, the Māori concepts of whakawhānaungatanga and manaakitanga are key to understanding the importance of including whānau in decision making for tāngata whāiora. We must emphasize, however, that whānau does not necessarily mean people who are related by blood, and it is important not to presume close family relationships. For many, the concept of ko wai au (who am I) is an integral part of the wellness journey as well as part of mana motuhake (control over one’s destiny).

To date, there has been scant recognition of the cultural influences on the people who are creating or using PADs. In this study, we have identified types of considerations that are important to Māori who are developing PADs, but these considerations may significantly differ from those that we and others have identified while using a Western cultural lens. For Māori service users, of critical importance is including whānau in the process of creating and using PADs. The current legal structure around PAD-making models does not accommodate this role for whānau; instead, legislation stresses that the instrument is personal to the individual and should be created and affirmed without external influences. Some culturally informed guidelines are needed in New Zealand to address how best to create Māori PADs. In particular, the next step needs to be kaupapa engagement to guide or direct further hui to discuss pou herenga and refine this concept into a working instrument. Our findings indicate that more researchers worldwide need to examine the influence of Indigenous cultures on the creation and use of PADs.