Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of home visiting models and the dedicated federal funding through MIECHV, only approximately 300,000 families received home visiting from evidence-based or emerging models in 2021, reaching less than 4% of the children and families who might benefit (

42). Additional MIECHV funding will further increase the numbers of families served, but closing the gap between need and available capacity requires sustainable, ongoing financing through policy changes that realize Medicaid’s untapped potential (

44). More than 85% of children served by MIECHV programs in 2021 were covered by public insurance (

42).

Medicaid provides health and long-term care coverage for low-income individuals in the United States, accounting for one out of every six dollars that the nation spends on health care (45). As of June 2022, together with its companion program CHIP, Medicaid covered more than 85 million people, including more than 40 million children (

46). In 2020, 12.7 million children under age 6 were covered by Medicaid, including more than 2 million infants in their first year of life—a critical opportunity to reach many mother-baby pairs (

47).

Medicaid’s reach to underserved communities also makes the program an important player in advancing equity in maternal and infant health. Medicaid pays for more than 40% of all U.S. births, including 65% of births to Black women and 60% of births to Hispanic women in 2019 (

48,

49). More than half of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native children in the United States are covered by Medicaid or CHIP (

50).

The federal and state governments, which together fund and administer Medicaid, spent more than $630 billion on the program in 2019 (

51). The federal government provides most of the funding, matching state spending at a rate that varies by state and by some services. Federal dollars pay for at least half the cost of direct services provided to individual beneficiaries (

45). Medicaid’s financing structure offers the possibility for more reliable and consistent funding for qualified home visiting programs, with capacity to follow billing processes for reimbursement. Congress does not have to act to renew or extend federal Medicaid funds. In contrast, other federal programs, including MIECHV, rely on congressional action to renew funding through the appropriations process.

The federal government, through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) within HHS, administers and oversees Medicaid. States and territories make policy decisions regarding eligibility, benefits, delivery systems, and other areas within federal standards and above federal minimums.

Medicaid’s Current Coverage of Home Visiting

Although some states have been covering home visiting services through Medicaid for decades, attention to Medicaid’s untapped potential has grown. In 2016, CMS and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provided guidance encouraging states to expand home visiting and clarifying ways in which states could use Medicaid (

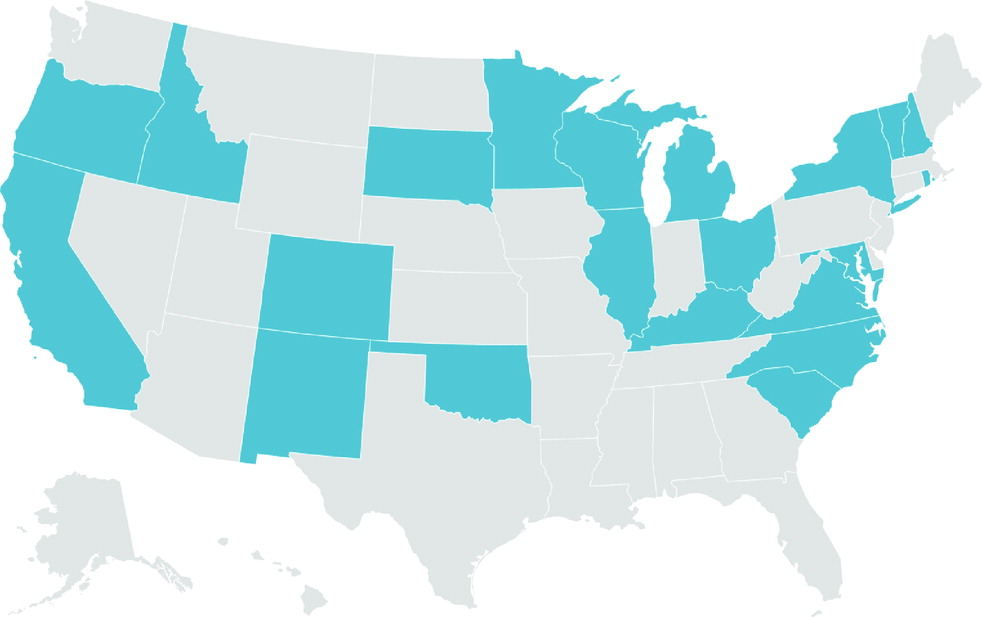

52). Twenty-one states now cover home visiting models through Medicaid for eligible pregnant women, children, or parents (

Figure 1) (

53–

55). Yet even in states that fund home visiting in Medicaid, services may not be available statewide or to all populations that need them. The National Home Visiting Resource Center estimates that an additional 18 million pregnant women and families with children under age 6 could benefit from home visiting, based on one of five prioritization criteria: caring for an infant, income below the federal poverty line, pregnant or parenting mothers under age 21, single or never married parents or pregnant women, and parents with less than a high school diploma (

42). Across states, home visiting programs reach between 0.1% (Vermont) to more than 9% (Michigan) of potential families (

42).

There is no specific home visiting benefit in Medicaid. Instead, states can choose from different authorities to cover many services included in home visiting programs (such as screenings, case management, family supports, and specific treatments, such as dyadic or family therapy). Most states cover home visiting through Medicaid’s Targeted Case Management benefit, which aids beneficiaries in accessing medical, social, educational, and other services and allows states to target services to specific populations and geographical areas (

56). States also use Medicaid’s comprehensive benefit for children, Early Periodic Screening Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT), pregnancy-related services for women, and section 1115 demonstration waivers to cover home visiting (

52).

To qualify for reimbursement, home visitors must meet Medicaid provider criteria set by the state (

52). Many providers are nurses and social workers, but more states are creating programs to reimburse community health workers, doulas, and peer mentors who may be employed by home visiting models based on each model’s staff qualifications (

57). Minnesota, for example, allows community health workers to serve as home visitors (

43). Use of community health workers as home visitors can help reflect the cultural and linguistic make-up of communities served, an important strategy for promoting health equity, especially among Black and Brown families, who have been historically underserved (

58). More state Medicaid agencies have also begun to allow for reimbursement of doulas for pregnant beneficiaries (

59,

60). Home visiting models, such as Parents as Teachers, may employ doulas as part of the service team (

61,

62).

A new state Medicaid option to extend postpartum coverage offers an important platform for home visiting services for new parents and their newborns. The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act gave states an option to extend coverage to pregnant women in Medicaid and CHIP from 60 days to 12 months postpartum. More than 35 states and the District of Columbia have implemented or moved to adopt this extended coverage period, with additional states likely to adopt it in the coming months and years (

63). States can use the opportunity of establishing the extended full year of coverage to provide home visiting benefits to many more new mothers and their newborns (

64). This can help advance maternal mental health and newborn screenings and connections to services, a goal that CMS established in its implementation guidance (

65). New Mexico, for example, is seeking to expand access to home visiting in Medicaid by making new models available to postpartum mothers and their children. The state submitted a waiver application and is awaiting federal approval to add four evidence-based home visiting models to an existing pilot program, making new expanded services available during and beyond the postpartum period (

66). The range of available models will help the state deploy multiple approaches to address a variety of unique family circumstances and help create a continuum of home-based services.

Expanding home visiting services through Medicaid can help connect families to other follow-up prevention and intervention services that they might need, including mental health and other follow-up services that Medicaid covers. Home visiting can also help Medicaid meet its obligation to ensure preventive screenings and needed care to children, which are required under Medicaid’s pediatric benefit EPSDT (

67,

68).

Scaling home visiting through Medicaid presents a clear opportunity to better align health and mental health in the postpartum period, complementing state policy initiatives to address high rates of maternal and infant mortality. Too often, mental health has not been a central focus of efforts to serve new parents and infants, despite its clear relationship to maternal and child health.

Finally, stronger Medicaid coverage policies would ensure a substantial, ongoing source of financing for home visiting. Leveraging Medicaid can help stretch limited public or private grants further, redirecting grant funding to develop new capacity or to pay for costs Medicaid does not reimburse. Having more comprehensive, stable financing, along with expanding the reach of home visiting, could create new incentives to build state and local home visiting capacity, which despite recent growth remains limited.

Additional Federal Actions to Accelerate Medicaid Financing for Home Visiting

The need and growing urgency to promote the mental health of mothers and children warrants strong federal leadership to expand home visiting through Medicaid. Federal policy makers can use a combination of legislative and administrative actions, which are described below.

Make evidence-based home visiting programs a required state benefit during pregnancy and through the child’s first year of life.

To expand and scale home visiting services, Congress should require states to cover Medicaid home visiting. For the first 5 years, this benefit would be optional in order to allow states to adopt new models and build home visiting capacity. At the end of that 5-year phase-in period, home visiting would become a required Medicaid benefit in all states. The mandatory benefit would apply to pregnant women and their children through the first year of an infant’s life and would be available statewide. Congress should also give states flexibility to extend the benefit for families with children ages 1 through 5. Congress should also provide grants to states to develop the capacity of home visiting providers, including strengthened or streamlined ability to effectively enroll in and bill for Medicaid reimbursement.

The new benefit would give states the ability to choose one or more HHS-reviewed models, along with a state option to include additional promising research-based models with emerging evidence. Congress should task the HHS HRSA, which operates HomVEE, with reviewing models that include or pair with specific mental health interventions, such as Moving Beyond Depression or Child First. States could choose from and deploy a variety of HomVEE-reviewed models to meet the new mandatory requirement, targeting different models to specific populations or geographic areas.

In 2020, Medicaid covered more than 2 million newborns in their first year of life and more than 10.5 million young children ages 2 to 6 years (

46). Making home visiting a Medicaid benefit would bring services to far more families, offering additional chances to access needed mental health services during a time of rapid change for the family. It would also complement Medicaid postpartum coverage extensions to 12 months, making the most effective use of the longer coverage period. The cost to the federal government of establishing this new mandatory benefit could be modest, because evidence suggests that some home visiting models are highly cost-effective and have benefits that exceed their costs (

69).

Clarify how states can effectively coordinate federal funding streams that support home visiting.

States seek to build more seamless and coordinated service delivery by maximizing use of MIECHV, Medicaid, and other federal and state funds. But lack of clarity on federal rules can inhibit the development of successful financing and service approaches. For example, federal law requires that Medicaid serve as the payer of last resort to ensure other available insurance sources pay before public safety-net dollars are spent. Congress has made exceptions to this rule in the case of some federal programs with more limited financing that provide direct services to children and families, such as the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act Part C Early Intervention, Families First Title IV-E prevention services, and Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant (

70). Congress should make a similar clarification exception with MIECHV to minimize implementation confusion when states seek to use funding sources together.

Require HHS to provide technical assistance to states on ways to advance home visiting.

Federal agencies, specifically CMS, HRSA, and the Administration for Children and Families, should support state efforts to take up home visiting and support state integration of home visiting across child-serving systems. Technical assistance can help states consider the best ways to help community-based organizations outside the traditional health system to bill Medicaid more effectively and to clarify mechanisms to use Medicaid alongside other federal funding. Congress should assign HHS this responsibility and provide additional funding for technical assistance.

Proactively identify strategies to maximize the reach of Medicaid with other federal programs for in-home parent and early childhood mental health services.

Some evidence-based prevention and treatment interventions that may be provided in the home (see table in the online supplement 1) may not be considered “home visiting” programs on the basis of HHS criteria but may qualify as eligible treatment services under Medicaid. HHS should coordinate across programs and funding sources to advance high-impact strategies for states to use Medicaid most effectively, along with other federal funding sources.