The Manitoba Schizophrenia Society, a community-based organization, provides support and information for people with schizophrenia and their families. During the discussion component of the society's information sessions for consumers, it was observed that women tended to remain silent and did not return for future sessions. This observation fueled the development of a needs assessment, which was conducted in three phases: focus groups, illness narratives, and a survey. The needs assessment results will ultimately be used in the design of a community-based program for women.

The research question for the needs assessment was: What are women's perceptions of their experience with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in the context of their life stages and corresponding health issues? This paper reports the major findings from the focus group sessions.

Methods

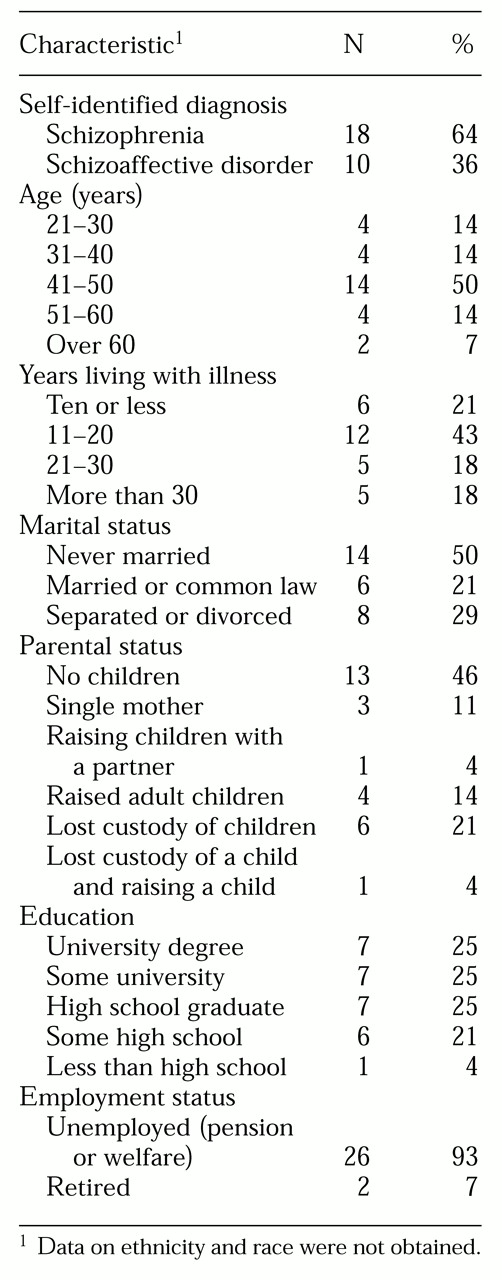

Potential focus group participants were recruited through advertisements and information sheets provided by health care professionals who work with this population. A purposive sampling strategy was used to select 28 women who identified themselves as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, who were living in the community, and who were willing to discuss the topic areas in a group format. The ability to give informed consent was predicated on living in the community. Each participant was paid an honorarium of $20. Characteristics of the participants are listed in

Table 1.

Focus group interviews were selected as the primary data-gathering method. This method was used to promote interaction among the women. Strengths of group interviews include their efficiency and the insights that emerge from the comparisons among participants' experiences and views (

8).

Each woman participated in one of five focus groups. The groups were organized around the women's age, marital status, and parenting responsibilities, and they ranged in size from four to seven women. All the groups discussed the same topics, such as experience with a psychotic illness, reproductive health, relationships, sexuality, parenting, menopause, and getting older. A range of broad, open-ended questions as well as focused questions were asked in order to facilitate discussion and the sharing of information.

The two-hour discussions were moderated by the program coordinator, herself a consumer, with a nurse researcher as assistant moderator. The moderator encouraged participation by asking each group member to compare her experience to the stated one, by letting the participants know that there were no right or wrong responses, and by encouraging different members to begin the discussion of a new topic. The sessions were audiotaped, and verbatim transcriptions were analyzed for thematic content by the program coordinator and two researchers. In this report, the direct quotations were taken directly from the transcripts.

Results

Even before the diagnosis of schizophrenia was made, loss became a dominant theme in these women's lives—loss of jobs, relationships, and children. As the diagnosis was made and symptoms of illness interfered with the women's ability to connect meaningfully to others, further losses occurred. Perceived rejection and criticism were commonplace. The pride and self-respect that develop out of accomplishments were often missing for these women, who were frequently denied many of the adult social roles that people use to define themselves.

The women felt that the health care system focused on their illness and that they had become invisible as women. In fact, they vacillated between seeing themselves as women and seeing themselves as "schizophrenics." Over time these internal conflicts took a devastating toll on their self-image and well-being. With a tenuous sense of self, the women began to perceive themselves as powerless to control their lives and vulnerable to the demands of others.

Work

Many of the women in the focus groups had at least some postsecondary education but had not held a job in years. Some had chosen either to be homemakers or to stay on disability pensions. Unlike men with schizophrenia, participants felt that as women, they could "get away with" not working; however, many wanted to work but faced the perceived risk of losing welfare or pension benefits if they pursued this desire. Still others were afraid they would not be able to handle the stress of working.

"I want to try to find a job, but I'm scared. I'm really scared that I'm going to get sick and I'm going to lose my job, and I'm going to have no money and how am I going to get back on welfare?"

The women expressed a deep indignation at the restrictive messages they were given about their inability to work or go back to school because of their diagnosis. Most of them, particularly younger women, single women, and those who had a university background, held on to the possibility of work in the future.

"I had a doctor about ten years ago who said I would never work again. I tore up all my résumés. I don't know if I'll ever work again, but I'm trying. I'm going to volunteer placement. And I want to work competitively some day."

Stigma and rejection

A keen sensitivity to stigma and the risks of disclosing their diagnosis ran through much of the discourse of these women. They either did not disclose their illness—thus compromising honesty and openness in relationships—or they chose to disclose and risk rejection.

"I don't tell. I just find that telling a person … they don't understand … especially with schizophrenia, they think they're going to be murdered by you, so I don't like to mention anything."

Adding to the prevailing sense of social stigma was the reality of the experiences of rejection, which made participants acutely sensitive to the messages they received from people around them. They felt judged as inferior and felt that they did not belong, no matter where they went. The following exchange between three mature women illustrates this point.

"I know, you feel you're a misfit in the eyes of other people."

"I don't feel it. I know it."

"Second-class citizen."

"An oddball."

"A freak."

"A weirdo."

"But it's not true. Everybody has feeling, and the feelings are similar."

"They call us emotional cripples."

Relationships and intimacy

Participants talked about the loss of friendships and relationships with family members who didn't understand their illness and with the difficulty they now have relating with and connecting to the world around them. Pervasive in this group of women, no matter what their age, was an overwhelming sense of loneliness and isolation. Knowing how to connect with other people in a way that was psychologically, physically, and emotionally safe was a challenge voiced over and over again. Making new friends or reestablishing connections with old friends was socially difficult and could be emotionally threatening, but not making friends resulted in lives of isolation and loneliness.

"It's really hard to find good friends, you know, like me. I had to stay away from people who drank, used drugs, and I'm in low-income housing … it's really hard."

The normal human desire for love and belonging created potential dangers of vulnerability and victimization for these women, both emotionally and physically. Intimate relationships had proved too stressful for many of them, and they cited the strain of relationships as a reason for relapse. Some women resolved their dilemma by choosing to be alone, while others still hoped to meet someone who would value them and understand their illness.

Complicating the fear of intimacy was the sense that the women felt preyed upon once their psychiatric history was known. Guilt and regret surrounded their stories of early promiscuity and prostitution, particularly while they were not taking medication.

"In my few sexual experiences I had when I went off my medication, I don't know why I was having sex. I certainly wasn't getting anything out of it. I wasn't getting paid. I wasn't getting any physical satisfaction. What was I doing? Just because I was sick, I wanted somebody to talk to me. I was lonely.… I felt like a reject, and it was the only way I could find some attention and make somebody talk to me."

Furthermore, many women reported histories of childhood abuse, rape, and physical abuse, resulting in an aversion to and fear of sexual intimacy.

Pregnancy and motherhood

Pregnancies were largely unplanned. Some women had not wanted to be mothers, while others had welcomed the role. Some women had abortions and regretted it later. One woman had an abortion under the delusion that the fetus was already dead. Some women chose to avoid pregnancy altogether because of their illness and were variously angry, sad, or resigned about their decision.

The question of whether or not to take medication during pregnancy had presented the women with the dilemma of risking their own mental health by going off medication or exposing the fetus to perceived harmful effects. Their experiences with physicians' advice during their pregnancies varied greatly.

"I knew I had to continue taking my medication because without my medication I'm helpless, and you can't be helpless when you're pregnant. What harm is my medication going to do to my child? I don't know. But I knew I couldn't stop taking it."

"I never took medication. The doctor wouldn't give it to me.… He said, 'You're okay so far—keep going, better for the baby.' I was really strained—emotionally suffering."

Mothers reported many benefits to having children, such as love, purpose, and identity and support as the children became adults.

"Children were a godsend because … it straightened me out. It's really hard, but it's rewarding to have children."

"My daughter has given back to me more than she ever took from me."

Some of these benefits were offset by stress, exhaustion, the difficulties of poverty, fear of the children's being apprehended, and fear of the children's developing schizophrenia. The difference between women who had raised children and those who had lost children to foster care or adoption seemed to be the presence or absence, respectively, of frequent, multiple supports, especially from family and day care.

"I gave up on parenthood a long time ago. I'll never forget those kids though. She called me 'mommy.' Now she calls everybody mommy. You start to get feelings for them, and then they're gone, and you don't think you have a reason to live … you don't think there's any more happiness for you. Gotta get your mind off of it. Pray for them. That's all you can do."

"When people ask me if I have kids, I just say no. It's less painful that way."

A deep sense of loss, grief, and some anger haunted the women who had lost children to child and family services. Years later these women were still struggling to process and integrate their experience of being judged an unfit mother. One woman continued to live in the same house for more than 20 years in case her child wanted to locate her.

Responsibility for illness

Cognitive-emotional dilemmas were pervasive in the women's talk about themselves, their illness, and their choices in life. Many women vacillated between knowing that they were not responsible for the onset of their illness and feeling that they somehow must be responsible.

"I don't know when the worst began. I don't know what my illness is, but the worst thing is I caused it. I mean I know I didn't, but it's like I caused it and … it feels like I caused it. I mean now that I realize it, I just watched myself go. And I know it's an illness and I know there's something wrong with me, but I can't believe I just watched myself go like that."

Physical health and interaction with a physician

Compounding emotional deprivation and social marginalization is the physical devastation of schizophrenia. The women spoke of the side effects of antipsychotic medications, such as weight gain, amenorrhea, decreased libido, lactation, and facial hair, which adversely affected their health and sense of self and femininity. Older women expressed a belief that long-term medication use had caused premature aging. The difficulty with losing weight was a major preoccupation for many women.

"I found that I put on a lot of weight over the last two or three years. I feel so uncomfortable.… I feel too self-conscious. I feel like everybody in the neighborhood knows there's this girl and something's wrong with her. I don't feel that womanly, and other times I feel that I am very much a woman."

"When I accepted the mental illness, I gained 80 pounds and got depressed. I literally watched my legs grow. Now that I'm older, it's harder to get the weight off."

Many of the women also seemed to have moved out of the mainstream information sources on women's health issues, even though the sample was relatively well educated. Generally, the women's talk revealed that they were not adequately informed about family planning, pregnancy, parenting, or menopause in light of their illness and its psychopharmacologic treatment.

"I was interested in the reproductive aspect of what … my pills do'cause I haven't had a period for a year.… The first one that I missed was when I started taking the pills. So I'd like to know if it's the pills."

Some women expressed reluctance to engage health care professionals in discussions about menstrual irregularities and sexuality. Others experienced lack of adequate response to their concerns about these issues.

"My doctor just does nothing. I say I haven't had a period for 14 months, and he doesn't say anything.… The doctors are so busy nowadays that they don't really have time to talk about things like that.… But I like him as a doctor … he's very good with my schizophrenia."

Fatigue was common among these women. It prevented them from attending to appearance and personal grooming as much as they would have liked and from getting things done. Much-desired social interaction was also prohibited by fatigue. Women struggled with the possibility that they were to blame for the lack of productivity related to fatigue.

"I find that I'm so tired. I tend to get stuck in one position. If I sit down I don't want to get up again. I don't know if it's my medication or whether I'm just plain lazy. I don't think I'm lazy."

The women faced the prospect of aging with some trepidation. They felt that the unpredictability of their psychiatric illness exacerbated an uncertain aging process and jeopardized their personal safety.

"Being sick and old is a bad combination. I'm afraid I might turn out to be a bag lady or something. If you're sick and you're not thinking clearly, something harmful could happen."

Hope and spirituality

Despite the expressed difficulty of their lives, these women nonetheless conveyed a pervasive and persistent sense of wanting life to improve and hoping that it could. They wanted friends, a job, and the energy to do things and to find some connection to the world and a purpose in life. Although they often expressed a degree of helplessness in managing their illness, they never expressed complete hopelessness about their lives.

Many women cited faith or spirituality as a source of strength, often found "deep within" themselves.

"I didn't start getting better'til I started going to church, and then stuff started happening … good stuff … and I really started to become attached to it. Like I wanted to, you know, live 'the way.' Like not wasting my time and just being sad all the time. I wanted to do something productive but didn't know what.… I'm searching, searching."

Spiritual connections were also found in creative activities such as writing, cooking, and gardening. Some women had developed their own philosophy about how they lived their lives, and they saw their illness within the context of their sense of self.

"I think it's important to see yourself as a person first. It's part of life that people with schizophrenia have the same desires as other people."

"It's always good to live in the present. It's good to have long-term goals but stop on the way and smell the roses, as they say. You find that when you get sick, you've got LOTS of time."

Discussion and conclusions

The strength of engaging women in discussion through qualitative interviews is that it enables them to reveal thoughts and feelings within the context of everyday living in a way that surveys and other quantitative methods cannot. In the face of multiple losses, social stigma, limited interpersonal contact, poverty, and feeling out of the information loop, these women described leading marginalized, deprived lives in the pervasive shadow of their illness.

The self-selection recruitment method employed in this study facilitated participation among women who were ready and willing to talk about their lives and connect with other women who shared similar experiences.

The limitation of our method of selection was that this sample is not representative of all women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Groups not clearly represented—despite our recruitment efforts—included women who had fully reconnected to society, aboriginal women, rural women, women of color, elderly women, and lesbian women.

The findings in this research have implications for practicing health care providers. The illness itself often takes precedence over other significant issues in women's lives, and practitioners may unwittingly contribute to their diminished quality of life, self-esteem, and sense of control by not contextualizing their treatment.

Practitioners can lessen the pain of a woman's dilemma in several ways: by engaging her in discussions of her options and providing support while she ponders which are best for her, by monitoring her response to the side effects of medications, by setting a climate that promotes discussion of sensitive subject matter, and by adopting an attitude of working with a woman in partnership.

The women in this study who had lost custody of children conveyed living with a deep sense of grief, a finding that is consistent with the work of Nicholson and colleagues (

9). Practitioners need to recognize the seriousness of such a loss.

It is important to note what the women did not talk about. Given the nature of their lives, we expected to see anger about their losses, difficulties, and uncertainties. Although some women alluded to feelings of anger, overt anger was not apparent in any of the focus groups. Conversely, limited pleasure or joy was expressed or conveyed as the women talked about even the positive things in their lives; in fact, the reality of their lives would suggest that they have limited sources of pleasure or joy.

Although sadness, depression, and fatigue may be assessed as negative symptoms, these feelings may also be a woman's response to losing control over her life and of having limited resources in a society that stigmatizes those with serious mental illness. Further investigation is needed to explore these alternative explanations.

The women were directly asked about substance use, but they were generally reluctant to reveal much about this topic, particularly the more mature women. Also, the subject of suicide was not introduced, and it rarely came up in the discussions. When one woman began to talk about suicide and dying, she was asked by another group participant not to be so graphic. The group method of data collection may not have been appropriate for discussion of these topics for this population. However, these are two significant areas to be pursued in future research.