Since the 1950s, psychiatrists have prescribed dopamine-D

2 receptor-blocking drugs to alleviate the hallucinations, delusions, and other positive symptoms of schizophrenia (

1,

2). Chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and other antipsychotic medications that were available before 1990 diminished most psychotic symptoms of patients with schizophrenia, but typically caused tremors, stiffness, bradykinesia, and other adverse neuromotor effects (

3). These drugs often did little to ameliorate the cognitive dysfunction, apathy, alogia, and other negative symptoms that account for much of the social disability associated with schizophrenia (

4,

5), and all patients who took them were at risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (

3).

Psychiatrists once regarded neuromotor side effects as almost inevitable, conventional features of antipsychotic therapy, and used the term "neuroleptic"—coined from Greek words meaning "seizing the nerve" (

6)—to describe how antipsychotic agents affected the nervous system. But the treatment of psychotic disorders changed dramatically in the 1990s, when four new antipsychotic medications—clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine—received approval from the Food and Drug Administration. These new medications were called atypical or novel antipsychotic agents because they could often be administered in doses that alleviated positive symptoms without causing the neurological side effects associated with the conventional agents (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13).

Clozapine reduces positive and negative symptoms in previously nonresponsive patients (

7), but the risk of developing agranulocytosis (

14), the need for frequent blood tests, and the resulting high cost of treatment limit its use to treatment-refractory patients. The other novel agents have no such limitations, however, and many prominent U.S. psychiatrists believe that they should be first-line drugs for treating psychoses (

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23). As this view becomes more dominant, psychiatrists may wonder whether treating patients with the older drugs will soon constitute malpractice, even when the treatment is administered in a manner that would have been deemed optimal practice just a few years ago.

In this article, we discuss reasons why conventional agents may still be used as first-line therapy in some settings, despite the apparent advantages of the newer antipsychotic drugs. We then describe several possible sources of liability that might arise from using conventional neuroleptics. We also examine how current case law might affect courts' and clinicians' thinking about other medicolegal issues associated with antipsychotic agents.

Novel antipsychotics and cost issues

If the new drugs were priced in the same range as the older D

2 blockers, psychiatrists would have little reason to hesitate about which type of drug to choose: for patients with new-onset schizophrenia or for individuals who do not have a good reason to take a conventional agent—for example, personal preference, excellent response to an older drug, or need for an injectable preparation—most evidence suggests that patients prefer the novel antipsychotics and would be "better off" (

23) if they were the drugs of first choice.

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project prescribes just such a pattern of care: despite their lower costs, older neuroleptics are relegated to a fourth-line position after trials of risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine have proved unsuccessful. Patients may also receive a depot neuroleptic after demonstrating poor compliance during their first trial of a novel antipsychotic medication (

17,

18).

However, novel antipsychotics usually cost far more than generic conventional agents. Medications for patients with schizophrenia often are purchased with managed health insurance dollars or with public funds administered through state budgets and Medicaid programs. Courts have ruled that in some circumstances these third parties are obligated to pay for qualified individuals' treatment with clozapine (

24,

25) and, presumably, with the other novel antipsychotics. However, private-and public-sector agencies also must administer psychiatric care within budgetary limits. These agencies thus potentially face the fiscal and moral dilemma of deciding whether helping patients avoid the risks of conventional neuroleptics is worth the added pharmacy expenses.

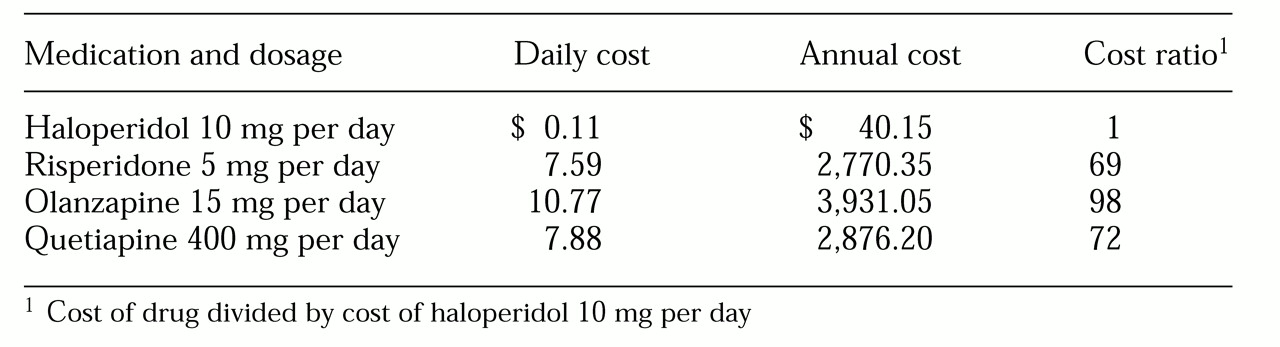

To illustrate these issues,

Table 1 lists the pharmacy costs as of October 2000 for generic haloperidol 10 mg per day and common doses of the new antipsychotic drugs at the authors' public-sector hospital in Ohio. Per-day costs of the new drugs are 70 to 100 times greater than that of generic haloperidol ($7.59 to $11.82 versus $0.11). Although the absolute differences are only around $3,000 to $4,000 per patient per year, the additional cost becomes important when one considers the budgetary implications for the 300 or so patients who receive antipsychotic treatment: about $1,000,000 per year, or nearly half of the hospital's salaries for staff psychiatrists.

Several published pharmacoeconomic studies suggest that using novel antipsychotics could reduce the total cost of treating persons with schizophrenia, chiefly by reducing the need for hospitalization (

26). For several reasons, however, we believe this notion should not be embraced unquestioningly.

Potential bias in study results. Neumann (

27,

28) notes that many pharmacoeconomic studies have credibility problems because of support by drug manufacturers. We do not believe that manufacturer-sponsored studies of atypicals have been intentionally biased, but three features of these studies may have tended to place the newer drugs in an overly favorable light.

First, treatment-resistant patients may have been overrepresented in some studies. Authors may therefore have overestimated the savings that would occur in typical populations of psychotic patients.

Second, several pharmacoeconomic studies have used data from pharmaceutical manufacturers' prerelease studies comparing novel agents to haloperidol 10 to 20 mg per day. Patients often receive such doses of haloperidol and equivalently high doses of other neuroleptics (

29). However, relatively few patients benefit from neuroleptic doses above the equivalent of haloperidol 5 mg per day (

30,

31), and evidence suggests that for neuroleptic-naive patients, haloperidol 1 to 3 mg per day is a reasonable starting dose (

32). A recent report suggests that the risk of developing tardive dyskinesia is less with risperidone than with a comparable dosage of haloperidol (

33). However, the evidence in premarketing studies favoring the novel drugs' ability to reduce negative symptoms might have been less striking had more modest doses of haloperidol—say, 2 to 5 mg per day—been used (

34).

A third point concerns weight gain and antipsychotic-induced diabetes mellitus. These medical problems often follow treatment with older antipsychotic agents, but their frequency and severity may be more pronounced among patients who take novel agents (

35,

36,

37,

38). Although lower risks of extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia are consistently touted in promotions of the newer drugs, increased risks of obesity and diabetes often go unmentioned. Our society greatly values thinness. We know of no study that compares attitudes about tardive dyskinesia and obesity, but if patients were asked about this point, a substantial fraction might prefer the risk of movement disorders to the risk of becoming fat.

Expected results versus findings from intent-to-treat studies. Early comparisons of total pre-and postclozapine costs in previously refractory patients who took clozapine successfully have suggested that lower use of hospitalization more than offsets the drug's high costs (

39,

40). However, intent-to-treat studies have found that clozapine improves many patients' functioning but achieves, at best, only modest calculated savings (

41,

42,

43). Modeling studies of risperidone and olanzapine also have suggested possible overall financial benefits (

44,

45,

46,

47), but intent-to-treat studies have not yet demonstrated such savings (

48).

Nonunanimity of findings. Not all studies have shown that novel agents save money or induce better compliance among patients. Schiller and colleagues (

49) found that costs and effectiveness did not differ among matched outpatients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone or with conventional agents. Binder and colleagues (

50) reported that only 29 percent of patients for whom risperidone was prescribed were still taking the drug two years later; reasons for discontinuation included noncompliance, nonresponse, and adverse effects. Coley and colleagues (

51) found that risperidone therapy did not reduce patient readmission rates and that the mean yearly costs for medication and hospitalization associated with risperidone therapy were nearly twice those of conventional agents.

Budgetary issues. Studies from France (

52) and Australia (

53) suggest that in countries with national health care budgets, atypical antipsychotics may generate substantial systemwide savings. In the United States, however, because of the way psychiatric care is funded, cost savings from using atypical agents may not be realized by the agencies or organizations that pay for the drugs. If savings do occur, they may be distributed unevenly, with some payers benefiting greatly and others very little. For many patients, the advantages of the new medications—and their associated cost savings—take many months to become apparent (

39,

40,

54), so financial benefits may not fall within the time horizon of a typical annual budget.

Theoretical versus actual savings. Finally, small reductions in patient bed-days may not produce any actual savings. Reduced use of hospital beds does not produce cash savings until hospitals have actually closed wards and reduced clinical and administrative payrolls. In many treatment settings, managed care or other policy decisions have already cut inpatient stays, leaving treatment agencies little room to realize savings to offset increased pharmacy expenses (

55). A lack of actual—or readily detectable—savings may help explain why the use of novel antipsychotics has remained limited.

"Stepped care": cash savings at a legal cost?

Two studies suggest that the atypicals lower treatment costs primarily for those patients who previously were nonresponders or high users of hospital services (

54,

56). However, published pharmacoeconomic studies typically evaluate treatment schemes in which patients from the outset receive treatment with either a conventional neuroleptic or a novel drug. It may turn out that the most cost-efficient antipsychotic treatment strategy is what we call a "stepped-care" approach.

Under this model, patients begin therapy with an older, less expensive antipsychotic in judicious doses, undergo conscientious monitoring for adverse effects and clinical response, and receive novel agents only if they do not have a good response to, or if they develop problems from, a conventional neuroleptic. Glazer (

57) has urged fellow psychiatrists to protest such policies, but some clinicians and administrators may conclude that first-choice use of efficacious but inexpensive drugs is justified by reasonable desires to marshal financial resources prudently (

58).

Adoption of a financially motivated, stepped-care policy should raise moral questions about whether it is acceptable for doctors to engage in such baldly utilitarian decision making, about what doctors should tell patients about the policy, and about the policy's possible effects on treatment relationships and clinical outcomes (

59). These important clinical and ethical matters are beyond the scope of this article, and we do not discuss them here. The following sections focus on possible legal consequences of stepped care and examine factors that could affect the outcome of lawsuits against psychiatrists who continue to prescribe conventional neuroleptics.

Evolving legal attitudes

Before the novel antipsychotic agents became available, U.S. legal decisions often described antipsychotic drugs in highly critical terms. The risk of adverse effects was central to several important cases that have heavily influenced the administration of these medications. In two cases, the U.S. Supreme Court made side effects a specific element in its 14th Amendment analysis of the right to refuse antipsychotic drugs and found that prisoners could not be forced to take the medications absent certain procedural safeguards (

60,

61). Judicial concerns about adverse reactions and the effects of medication on thought processes have figured prominently in state court decisions concerning administration of antipsychotics to involuntarily hospitalized patients (

62,

63,

64) and to death row prisoners who are found incompetent to be executed (

65).

The tone of some recent appellate decisions on forced treatment with atypical antipsychotics is distinctly different. Although courts often have not distinguished between refusals of conventional antipsychotics and refusals of novel agents (

66,

67,

68,

69,

70), in some cases the superior efficacy of the novel antipsychotics and their lower risk of side effects have been cited as reasons to impose involuntary treatment. These rulings have not been concerned with physician liability, but we discuss them here because they illustrate judicial attitudes that could influence decisions concerning novel agents and the standard of care.

Several Minnesota cases describe the advantages of atypicals as reasons to administer clozapine against a patient's wishes. For example,

In re Tyler (

71) states: "Clozaril is known to be more effective with some patients than other neuroleptics, and he may not experience many of the side effects which Prolixin causes. …[A]n atypical neuroleptic such as risperidone or Clozaril may better treat appellant's remaining problematic behaviors, and there is little disadvantage to either medication."

Another Minnesota appellate-level decision (

72) cited evidence, heard by the trial court, that "Clozaril is a better medication … because it greatly reduces [the patient's] symptoms of mental illness and makes him more amenable to other treatment while avoiding the risk of tardive dyskinesia." The appeals court even approved of administering clozapine to an unwilling patient by nasogastric tube: "If the medication is medically necessary, the means to administer it must be medically necessary as well." Recently the New York Supreme Court approved of giving an incompetent patient involuntary antipsychotic therapy that "in turn would allow [the patient] to take newer antipsychotic drugs which have no [sic] side effects" (

73).

Appellate-level right-to-refuse cases have thus far left the choice of medication "to the discretion of the medical professionals" (

74). It sometimes seems, however, that courts might prefer that psychiatrists prescribe novel agents. In

Dibley v. Gomez (

75), for example, the appellate court was troubled that a patient was not receiving "the newer medications that do not precipitate the adverse side effects associated with the older neuroleptics.… We must, however, leave to the treating professionals the decision of how best to proceed."

Proper use of traditional neuroleptics

According to the American Psychiatric Association's April 1997 guideline for treating schizophrenia (

9), either conventional or atypical antipsychotics constitute acceptable initial therapy. By 1999, however, novel antipsychotics had become the dominant first-line choice among expert psychopharmacologists (

19). Some psychiatrists have speculated that prescribing conventional neuroleptics might now constitute grounds for a lawsuit, even if the treatment adhered to practices sanctioned by the APA guideline.

For example, National Institute of Mental Health director Steven E. Hyman (

76) has suggested that trying to use conventional agents to save money might be a false economy; the cost of defending "only one or two lawsuits" brought by patients who received conventional antipsychotics and developed tardive dyskinesia would be enough "to make up the difference between the cost of generic standard antipsychotics and the atypical antipsychotic medications currently available." Kaye and Reed (

21) made a similar argument, noting that especially in fiscally strained treatment systems, avoiding "expensive civil rights litigation arising from patients developing TD [tardive dyskinesia] from older medication is as important an economic consideration as the initial cost of medication."

Indeed, a few malpractice cases have resulted in massive judgments for improperly using or monitoring the effects of conventional neuroleptics (

77,

78). Patients can always sue doctors or agencies for using these drugs, and defending such suits might indeed be expensive. In the following subsections, we consider factors that might influence whether a malpractice suit or civil rights action would be successful.

Use of conventional neuroleptics per se as malpractice. A malpractice action might assert that, in the era of atypicals, it is a compensable deviation from the "standard of care" if any patient suffers damage such as tardive dyskinesia from neuroleptic therapy, even if the physician who prescribed the drug followed practices that were acceptable only a few years ago. The prevailing standard is usually established at trial through expert testimony about "the average degree of skill, care and diligence exercised by members of the same medical specialty community in similar situations" (

79). Although the law generally does not require a doctor to choose any particular treatment, the treatment chosen must receive the support of "a respectable minority" of physicians, and the practitioner must follow "acceptable procedures of administering the treatment as espoused by the minority" (

80).

Two reports on U.S. prescribing patterns in 1999 found that most prescriptions for antipsychotic medications were for conventional neuroleptics (

5,

81); worldwide, just 10 percent of prescriptions are for atypical agents (

82). Available data thus suggest that prescribing conventional neuroleptics still falls within the prevailing standard of care, notwithstanding the recommendations of expert panels.

Failure to inform. Although a malpractice suit probably would not succeed if it simply alleged that it was improper to prescribe a conventional neuroleptic, failure to tell patients about the availability and possible advantages of newer drugs might result in physician liability. The only appellate-level case concerning novel antipsychotics and psychiatric malpractice—

O'Keefe v. Orea (

83)—has already touched on this matter. In this case, Ruth O'Keefe sued the Florida psychiatrist who treated her son, Christopher, after Christopher attacked his parents and killed his father. A consultant who had evaluated Christopher had suggested that clozapine might be an effective treatment. The treating physician had not discussed this recommendation with Christopher's parents, and the lawsuit asserted that this omission (along with many other alleged errors) constituted negligence.

A lower court dismissed the suit, but an appellate court reinstated it, holding that Mrs. O'Keefe had valid grounds for a malpractice suit under Florida law. The appellate court said that the psychiatrist had "a duty to inform Christopher's parents concerning … the diagnosis of other physicians who had observed Christopher, together with his personal treatment recommendations and the treatment recommendations of other physicians." The

O'Keefe ruling is consistent with informed consent requirements outlined in

Canterbury v. Spence (

84): doctors have a duty to tell patients about "the inherent and potential hazards of the proposed treatment, the alternatives to that treatment, if any, and the results likely if the patient remains untreated."

Use of conventional neuroleptics as a civil rights violation. Conceivably, patients detained in government-run institutions—such as state hospitals—who receive treatment from physicians acting on behalf of those institutions might file civil rights actions alleging that administration of a conventional neuroleptic rather than a novel antipsychotic drug amounts to a violation of their civil rights.

Most U.S. legal decisions concerning institutionalized patients' access to novel antipsychotics have focused on clozapine, because it is the atypical agent that has been available the longest. Two cases—

Visser v. Taylor (

25) in Kansas and

Alexander L. v. Cuomo (

24) in New York—established that state Medicaid programs must include clozapine in formularies and cover its costs; that is, they must make clozapine available to patients. As the following three cases indicate, however, no U.S. court, as of September 2000, has faulted a psychiatrist or a government agency for not prescribing a novel antipsychotic, nor has any court said that psychiatrists, institutions, or public agencies must treat a particular patient with a particular drug.

In a 1993 case, a district court dismissed the civil rights suit of a convicted rapist who was committed to the Bridgewater, Massachusetts, Treatment Center for Sexually Dangerous Persons. He claimed that his past treatment experience suggested "that his only hope of release might rest on securing clozapine therapy" (

85). The prisoner had been offered several psychosocial treatments, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit upheld the lower court's ruling that "mere failure to provide this one recommended treatment was insufficient to demonstrate a genuine issue of material fact."

In

Gates v. Shinn, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided that a 1990 consent decree requiring California "to provide appropriate psychiatric care for prisoners" did not create a mandate to make clozapine therapy available to inmates (

86). In reaching this decision, the court cited an affidavit filed by the prison's psychiatric expert, which said that prison staffing levels made it difficult to administer clozapine safely. The expert added, however, that "new medications with potentially less risk are about to come on line in psychiatric practice." If clozapine's risks indeed were the central factor in

Gates, the court might reach a different conclusion about access to the other atypicals.

In a 1997 opinion (

87) stemming from the 1971

Wyatt v. Stickney case (

88), a federal court ruled that failure to use clozapine in Alabama state facilities was not a violation of its standards for administering medication. Although the court criticized clinicians for sloppy record-keeping and for leaving long-term patients "on stagnant medication regimes … the court cannot, and should not, fault the defendants for deciding, in their professional judgment, not to use [clozapine]. Moreover, the court's duty does not extend to such minuscule oversight."

Treatment choices and potential future liability

Medicolegal considerations may someday be linked to a psychiatrist's drug choice in specific clinical circumstances, such as perceived need for a depot antipsychotic. None of the atypicals is yet available as a long-acting injection, and clinicians may favor depot preparations for noncompliant patients who are at high risk of becoming violent shortly after hospitalization (

89). Suppose a person on outpatient commitment developed tardive dyskinesia from a depot neuroleptic that he was required to take in order to stay in the community. Might the patient try to sue a psychiatrist for not offering a trial of an oral preparation of a less noxious atypical antipsychotic and insisting on the compliance-guaranteeing depot preparation? Successful suits for tardive dyskinesia have been uncommon (

21,

90), but over the next few years, changing perceptions of the older drugs may increase their likelihood of success.

The limited effectiveness of conventional agents in ameliorating negative symptoms and cognitive deficits constitutes a second clinical area in which treatment choices could become a source of malpractice or civil rights litigation. A lawsuit could assert that a patient would have benefited from an atypical antipsychotic drug—perhaps by becoming able to live successfully in a less restrictive setting—but suffered substantial "damage" or deprivation of liberty because he did not receive an atypical agent. Such a claim might draw support from prerelease studies suggesting that patients with schizophrenia who have negative symptoms stand a good chance of benefiting from the newer drugs (

11,

12,

13) and that atypicals may improve cognitive functioning (

5).

Some recent reports have questioned whether atypicals actually ameliorate the "deficit" negative symptoms intrinsic to schizophrenia or merely the "secondary" negative symptoms caused by neuroleptic side effects, lack of social stimulation, or intrusion of positive symptoms (

91,

92,

93). But as data accumulate on the long-term benefits of the newer drugs, a successful suit based on failure to optimize functioning may become plausible.

A related set of claims might devolve from psychiatric patients' rights under the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) (

94). In a 1999 case concerning two hospitalized Georgia patients who doctors believed could live outside a hospital, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the ADA obligated the state to find and pay for community placement (

95). Holding "that unjustified institutional isolation of persons with disabilities is a form of discrimination," the majority in

Olmstead v. L.C. concluded that Title II of the ADA requires states "to provide community-based treatment for persons with mental disabilities when the State's treatment professionals determine that such placement is appropriate, the affected persons do not oppose such treatment, and the placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the State and the needs of others with mental disabilities."

The significance of Olmstead will ultimately be determined by future decisions in which lower courts implement this general principle. But because several studies have shown that atypical agents improve patients' chances of successful tenure in the community, Olmstead might permit a patient to argue that an institution's failure to use the newer drugs amounted to ADA-prohibited discrimination.

A final area of potential treatment-choice litigation concerns aggression by patients toward themselves or others. Pinals and Buckley (

96) recently reviewed a small but growing literature that suggests that the atypical agents may be more effective than the conventional neuroleptics in reducing the likelihood of patients' acting violently. Conceivably, if a neuroleptic-treated patient with a known propensity for violence caused harm to a third party, the injured party might sue the patient's psychiatrist, arguing that by failing to use a novel antipsychotic, the clinician negligently failed to take reasonable measures to reduce a foreseeable risk. A similar claim might be brought by family members of a neuroleptic-treated patient who had committed suicide, in view of recent evidence suggesting that atypical agents may reduce depressive symptoms and suicidality in patients with schizophrenia (

97).

Conclusions

Courts are just beginning to address legal issues arising from the arrival of atypical antipsychotic drugs. In decisions published through September 2000, courts have deferred to professionals' judgments about the choice of antipsychotic medication and have not condemned use of conventional antipsychotic drugs. Yet as legal decision makers become more aware of the novel agents, their attitudes toward antipsychotic therapies are evolving. There are signs, in some forced-medication cases, that courts view atypical antipsychotic drugs more favorably than they do conventional neuroleptics.

Traditional malpractice law requires the psychiatrist to "possess the degree of professional learning, skill, and ability which others similarly situated ordinarily possess; exercise reasonable care and diligence in the application of his knowledge and skill to the patient's care; and use his best judgment in the treatment and care of his patient" (

98). Recently published data suggest that conventional agents still account for a substantial fraction—and across the world, a majority—of antipsychotic prescriptions (

5,

81,

82). For now, prescribing conventional neuroleptics as first-line therapy still falls within the standard of care.

However, the informed consent doctrine outlined in

Canterbury v. Spence (

84) and medicolegal texts (

99) holds that when physicians recommend a course of therapy, they have a duty to provide information about other treatments. As Klerman (

100) put it, "The patient has the right to be informed as to the alternative treatments available, their relative efficacy and safety, and the likely outcomes of these treatments." In

O'Keefe v. Orea (

83) —which to date is the only malpractice case dealing with novel antipsychotic drugs—a Florida appellate court held that a psychiatrist had an obligation to provide information about the potential benefits of clozapine. It seems only logical that courts would apply the principles of

O'Keefe and

Canterbury to all novel antipsychotic agents. This would mean that doctors who choose—for clinical or financial reasons—to prescribe conventional neuroleptics are legally obligated to tell patients about the newer antipsychotics.

Klerman (

100) has argued that psychiatrists have a clinical duty "to use effective treatment. The patient has the right to the proper treatment. Proper treatment involves those treatments for which there is substantial evidence." A growing number of U.S. psychiatrists—though not all (

58)—believe that scientific evidence unambiguously supports the use of novel antipsychotics as first-line therapy and that older drugs should have only a minor, limited role in the treatment of psychotic patients. Many psychiatrists also believe that proper, well-monitored use of conventional neuroleptics may soon leave doctors vulnerable to being sued successfully for malpractice or violations of civil rights. This point has not yet been reached, however. Whether it ever will remains a matter of speculation.