The growing evidence that persons with severe mental illness have active sexual lives runs contrary to the prevailing stereotypic impression that schizophrenia is synonymous with either asexuality or with bizarre, illness-related sexual practices (

1). Cournos and colleagues (

2) reported that at least 50 percent of the persons with schizophrenia in the sample they studied were sexually active, and many had multiple partners and were casual about contraceptive and other safe-sex practices that would diminish their risk of exposure to HIV.

When dealing with sexual behavior between inpatients, hospital staff, in the absence of administrative direction, have to resort to idiosyncratic and inconsistent responses, most often based on their own sexual mores (

3). Staff appreciate clear administrative rulings on how best to uphold their duty to be responsible for and protective of patients while not infringing on patients' personal liberties (

4). Because of fear of litigation, hospitals may be reluctant to address the issue of sexual behavior openly and to provide clear guidance to staff. Holbrook (

5) described how one hospital faced severe public censure, repeated investigations, threats of litigation and closure, and declines in staff morale when a sexual incident between two patients was poorly handled (

5).

In an earlier study, we reported that 50 of 57 hospital administrators (88 percent) responding to a survey considered the sexual behavior of inpatients at their facility to be problematic (

6). Forty-seven respondents (83 percent) indicated that they had a formal policy to address this concern. To learn more about how issues of inpatient sexuality are addressed, we collected and analyzed policies from these and other state facilities.

Methods

The 47 respondents from the previous study who indicated that they had a formal policy on inpatient sexuality were directors of state psychiatric facilities in nine states: New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington. They were recontacted in 1997 by letter to request a copy of their policy. We contacted other states for lists of their state psychiatric facilities. Seven states responded—Alabama, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin—naming a total of 34 additional facilities. In 1997 these facilities were contacted by letter for the first time to request a copy of any policy on sexuality, if such existed. We followed up the letter by telephone or fax to try to secure a response.

Policies were reviewed by the second author for explicit definitions and distinctions between various sexual behaviors; for the presence and content of statements about patients' rights and personal autonomy, duty to protect, competency to consent, and staff guidance and education; and for instructions on the management of sexual incidents. These coding categories were selected based on a thorough review of the literature and are consonant with guidelines that were subsequently published by other researchers (

8).

Results

Of the original cohort of 47 hospitals from the earlier study, 23 (49 percent) forwarded their policy. Of the second cohort of 34 hospitals, 18 (51 percent) responded to our request. Ten sent an explanatory letter; many of these respondents noted that they had no formal policy or were struggling to develop one. Eight hospitals provided an actual policy. Thus 31 policies were reviewed.

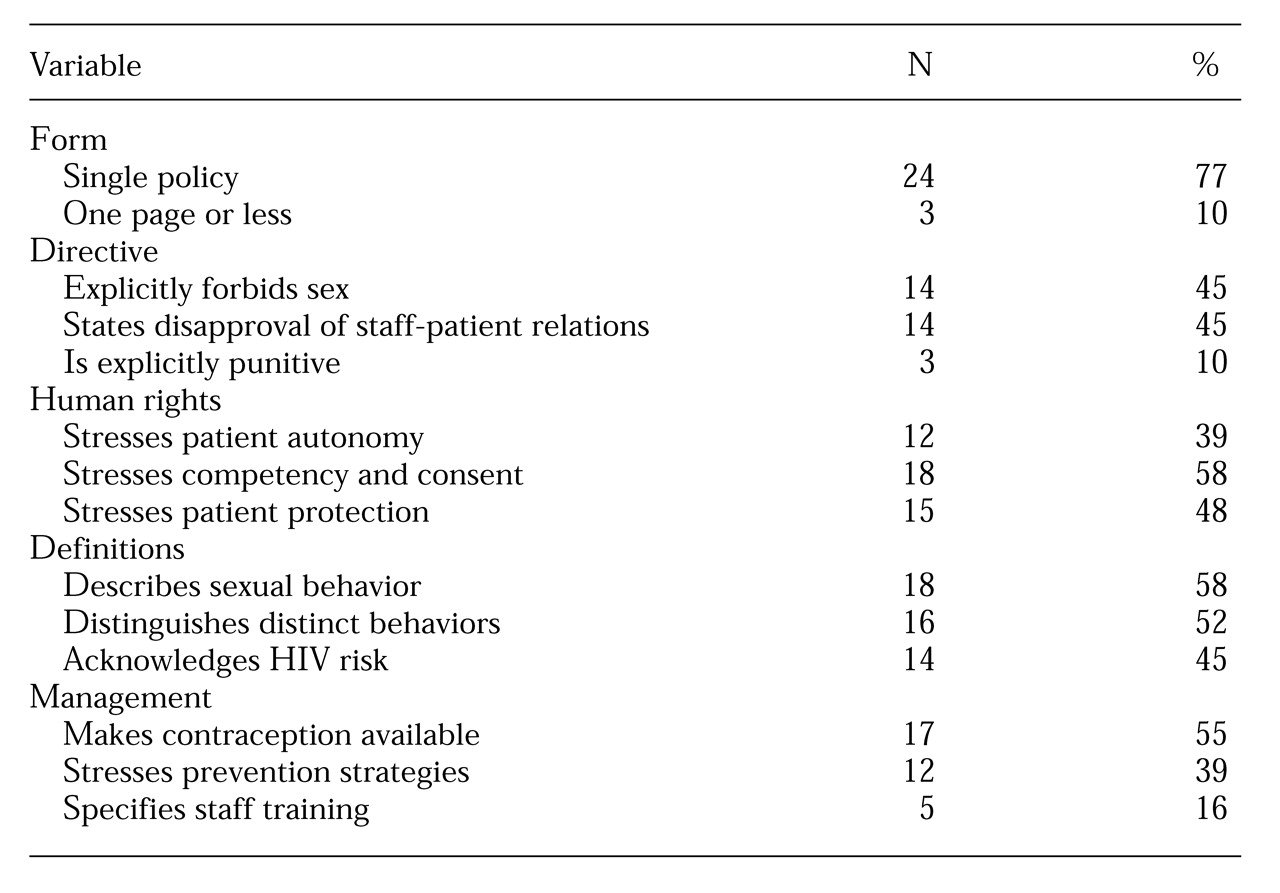

The characteristics of the policies are summarized in

Table 1. The most detailed information was provided on the management of sexual assault. Some policies included directions and responsibilities specific for each discipline and stated explicitly how corroborating physical evidence of assault should be collected.

Eighteen of the 31 policies (58 percent) had statements on contraception or on prevention of sexual relations through sex education and counseling. However, only five (16 percent) specifically mentioned staff training. Details on the content of training were not provided, although one policy emphasized that staff members should be instructed not to tease patients who engage in sex or not to use derogatory sexual terms.

More than half of the policies addressed the issue of competency, but to various levels of detail. One policy emphasized the distinction that legal competency or status was not the major determinant of the capacity to consent to sexual acts and that adults who were declared incompetent may or may not have the capacity to consent to sex, just as legally competent adults may or may not have such capacity. The determination of capacity was stated to be the responsibility of the attending psychiatrist.

Many policies began with a preamble or a philosophical statement that acknowledged the complexity of this issue. One policy emphasized that patients are entitled to rights of freedom of expression as described in the First Amendment, but at the same time they are entitled to an environment free of harassment. Another policy enumerated basic sexual freedoms—freedom of sexual thought (that is, fantasy), of sexual identity, of autoerotic sex in private, of consensual sex that occurs in private and with dignity, and of choice of contraception. However, this policy included the caveat: "provided [the sexual freedoms] do not represent an infringement on others' freedom."

Several policies affirmed the appropriateness of limited physical contact, such as hugs and farewell embraces, as a means of expressing affection. One policy succinctly stated that the expression of patient sexuality should be "consistent with reality, with the hospital's primary mission, and with the law. Principles guiding this philosophy are the promotion of patient dignity, privacy, the protection of vulnerable patients, the fostering of personal and environmental safety, and encouragement of responsible sexual practices."

Another policy gave some guidance about which patients might appropriately engage in sex. Staff members were asked to consider the patient's current length of stay and expected duration of hospitalization and the opportunity for home passes; capacity to consent to sex; current mental status; level of comfort with sexual activity; and the presence of medical conditions that might compromise or complicate sexual expression, such as physical illnesses or sexually transmitted diseases. One policy prefaced its guidelines with key references from the psychiatric literature.

Discussion and conclusions

Consistent staff response, guided by unambiguous administrative direction, is necessary both to protect patients' rights and to minimize litigation for sexual relationships between patients in psychiatric hospitals. In the late 1970s Keitner and Grof (

7) surveyed 70 psychiatric units in Canada about inpatient sexuality; no unit had even a written policy. More than 15 years later, Welch and Clements (

8) developed a comprehensive policy to facilitate, under carefully monitored circumstances, consensual sex between inpatients. Although their staff expressed concern at the adoption of a "modern-day" approach to human sexuality among inpatients, the absence of a policy was viewed to be of greater medicolegal risk because it could be construed as negligent omission in law. Mossman and colleagues (

9) reached a similar conclusion and advocated particular attention to this issue in long-stay psychiatric facilities.

The results reported here are consistent with those of our earlier study (

6) and with informal impressions that hospitals vary widely in their attention and management approach to sexuality of inpatients. However, this study was neither exhaustive nor comprehensive in its attempt to reach all hospitals and states. The response rate was low. Furthermore, facilities that either lacked a policy or were uncomfortable with their policy may not have replied to our request. Thus the representativeness of the sample of policies and practices cannot be determined. Also, policies may not reflect practices because they may become outdated or may not be actively monitored or enforced. It is also apparent that the presence of a policy, irrespective of how explicit it is or the extent of staff training, does not mean that staff will follow it.

Despite these substantial shortcomings, collation of such policies has not been previously reported. Review of the policies provides useful insights into the commonality of this dilemma and how individual hospitals address the issues raised by patients' sexuality.

One respondent concluded, "Sexual activity among patients is a reality and one with which we must deal and not put our heads in the sand."

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation for support.