Nearly 30 years ago, the senior author established a neuropsychology research program at the Topeka Veterans Affairs Hospital and subsequently moved the program to the VA facilities in Pittsburgh. The primary aim of the program was to study brain-behavior relationships in a variety of clinical groups through neuropsychological assessment. An extensive database has been developed, now comprising data on more than 3,000 inpatients and outpatients from either the Topeka or the Pittsburgh VA hospitals. As part of this research, data on study participants' length of illness, age of onset of illness, length of hospitalization, number of hospitalizations, and related clinical and demographic characteristics are gathered from medical records.

The study reported here used data from the research project to investigate possible differences in patterns of hospitalization during two different eras of treatment and management policies for patients with chronic schizophrenia. Data for two cohorts of male veteran patients with schizophrenia are reported here. The first group consists of patients who were hospitalized at some point during the years 1965 through 1975. The second group consists of patients hospitalized at some point during the years 1991 through 1994. Differences in neuropsychological findings for the two cohorts, reported elsewhere, were found to be minimal (

1). That is, the level and pattern of cognitive function were remarkably similar between the two groups.

During the era of the first cohort, treatment for chronic schizophrenia generally involved long-term care in institutional settings. Although antipsychotic medications were available, the practice of stabilizing patients on medication and returning them to the community after a brief period of hospitalization was rarely implemented. Sheltered environments such as halfway houses and therapeutic communities were only beginning to appear, as were outpatient clinics for treatment of patients with schizophrenia in the community.

By the time the patients in the second cohort were hospitalized, these policies and practices had largely been abandoned. Most patients with schizophrenia no longer were institutionalized for lengthy periods; they typically were discharged from the hospital shortly after being stabilized on medication. This policy change was apparently driven by improvements in the effectiveness of medication, the increasing availability of community treatment and rehabilitation facilities, and the concern that had emerged about numerous detrimental effects of long-term institutionalization (

2,

3). The outcome literature concerning brief hospitalization has produced somewhat inconsistent results, but there appears to be general agreement that a longer stay does not improve patient outcome or reduce the risk of subsequent rehospitalization (

4,

5,

6).

Methods

Subjects

The first cohort consisted of 136 male patients with schizophrenia who participated in the neuropsychology research program while hospitalized during the years 1965 to 1975. Diagnoses of schizophrenia for the first cohort were made during that period using

DSM-II criteria (

7). The diagnoses were established for this research through retrospective review of clinical records to identify cases in which

DSM-III (

8) or

DSM-III-R (

9) criteria were later explicitly indicated.

The second cohort consisted of 73 hospitalized male patients with schizophrenia who participated in the research program while hospitalized between 1991 and 1994. The diagnoses of these patients were based on

DSM-III-R criteria and were obtained using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (

10). A board-certified psychiatrist clinically confirmed the diagnoses.

Essentially all subjects in both studies were stabilized on appropriate medications available at the time and were able to cooperate with procedures for neuropsychological testing. Stabilization was evaluated based on patients' ability to cooperate with the testing and lack of change after prescription of a given medication and an increase in dose level.

Procedure

The variables considered in this research were age, age at onset of schizophrenia, years of education, number of months of illness, number of months of hospitalization for schizophrenia, and number of hospitalizations for schizophrenia. The data were collected from interview material and medical records. Instances in which the required information was not available or definitive were treated as missing data. Data were analyzed using t tests comparing the two cohorts on these variables.

Results

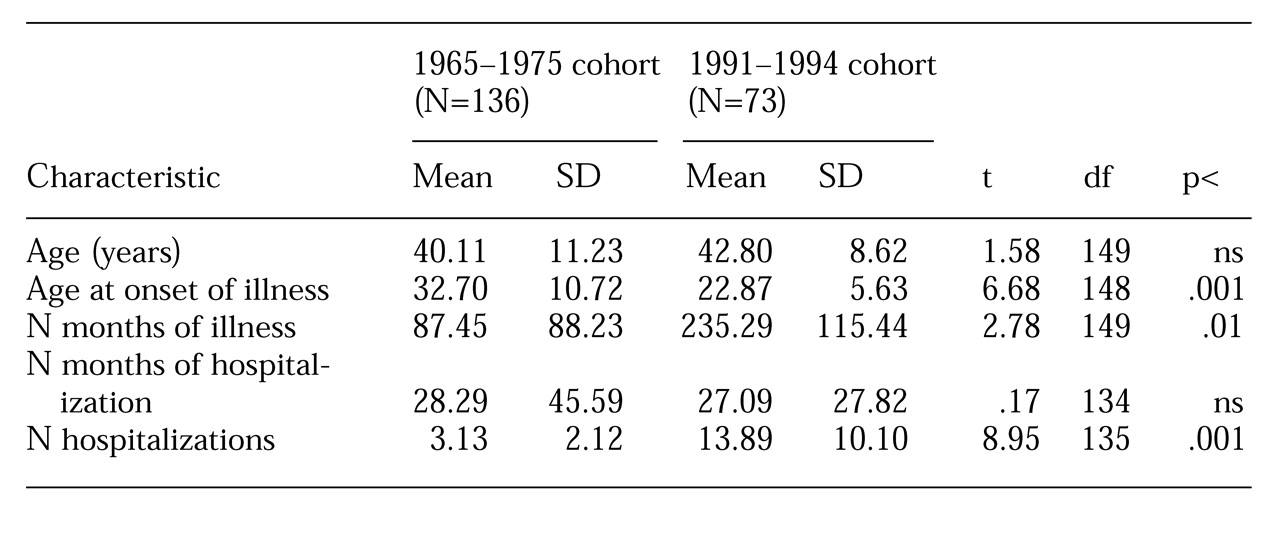

Comparisons between the various clinical and demographic variables are presented in

Table 1. Although the cohorts differed significantly on several variables, the most pertinent findings were the lack of a significant difference between cohorts in length of hospitalization and a highly significant difference in the number of hospitalizations. Other significant differences included age of onset of illness and months of illness. The first cohort had a later age of onset and a shorter length of illness.

Discussion and conclusions

The major finding is that individuals treated for schizophrenia under the older policy of longer hospitalization did not actually remain hospitalized longer than patients treated under the newer rapid discharge policies. However, we attribute this result to characteristics of the two cohorts themselves rather than to change in treatment policy, particularly because several other significant differences were found between the cohorts. We suggest that the other differences are at least partly artifacts of the nature of the VA patient population and do not appear to be associated with differing patterns of hospitalization.

Thus the difference in length of illness may be related to the composition of the cohorts. The first cohort consisted largely of veterans of the Korean conflict who were evaluated about ten years after the end of the Korean conflict. The second cohort consisted largely of veterans of the volunteer military, with some veterans of the Vietnam conflict. However, the second cohort was evaluated more than 20 years after the end of the Vietnam era, and no major intervening war took place during that 20-year period. If one views war as a precipitating event for onset of schizophrenia, the second cohort had experienced more time since such an event than the first cohort and therefore had more time during which to be ill. Similarly, the extreme youthfulness of many Vietnam-era servicemen may explain the difference in age of onset.

The more recent cohort encompassed a shorter time span than the older cohort; if the time spans had been equal, the more recent cohort may have experienced a lengthier period of hospitalization. Such a contingency would reinforce the hypothesis that short hospitalization is not associated with reduced total length of hospitalization. Unfortunately, that matter must be left undetermined, because changes in health care policy have essentially eliminated long-term hospitalization for new cases of schizophrenia.

Another possibility is that changes in the population of veterans who use the VA health care system have included development of a subpopulation of veterans with schizophrenia who are particularly prone to relapse due to numerous factors such as homelessness, substance abuse, and noncompliance with medication schedules. Indeed, a limitation of this study is that the results may not apply to nonveterans. We suggest that although the two cohorts may differ in the ways described here, the finding that rapid discharge associated with numerous rehospitalizations does not appear to reduce total length of hospitalization for patients with schizophrenia would seem worthy of consideration. This finding does not suggest a need to revert to long-term hospitalization but rather a need to improve methods for effective relapse prevention.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.