Behavioral health benefits have long been subject to greater restrictions than other health benefits. However, the gap between behavioral and other health benefits widened during the 1980s and 1990s as health plans and purchasers sought to contain rising costs. The Mental Health Parity Amendment (P.L. 104–204), which took effect in 1998, sought to redress these inequities by requiring companies with 50 or more workers to set the same annual and lifetime spending limits for mental health care as for other health benefits. This column provides a snapshot of mental health coverage across two different types of health plans, health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and indemnity insurance plans, in 1997, immediately before enactment of the parity law.

Our analysis used data from the 1997 Employee Benefits Survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The survey included a national sample of 1,945 U.S. employers with more than 100 workers. Because smaller employers generally offer less generous health benefits packages (

1), the estimates likely represent the upper limits on rates of mental health coverage by employer-based health insurance in the U.S.

Of an estimated 29.3 million people working in medium and large firms in 1997, more than 95 percent had at least some inpatient or outpatient mental health coverage. However, only a small minority had the same level of coverage for both mental and medical benefits—12 percent for inpatient care and 2 percent for outpatient services.

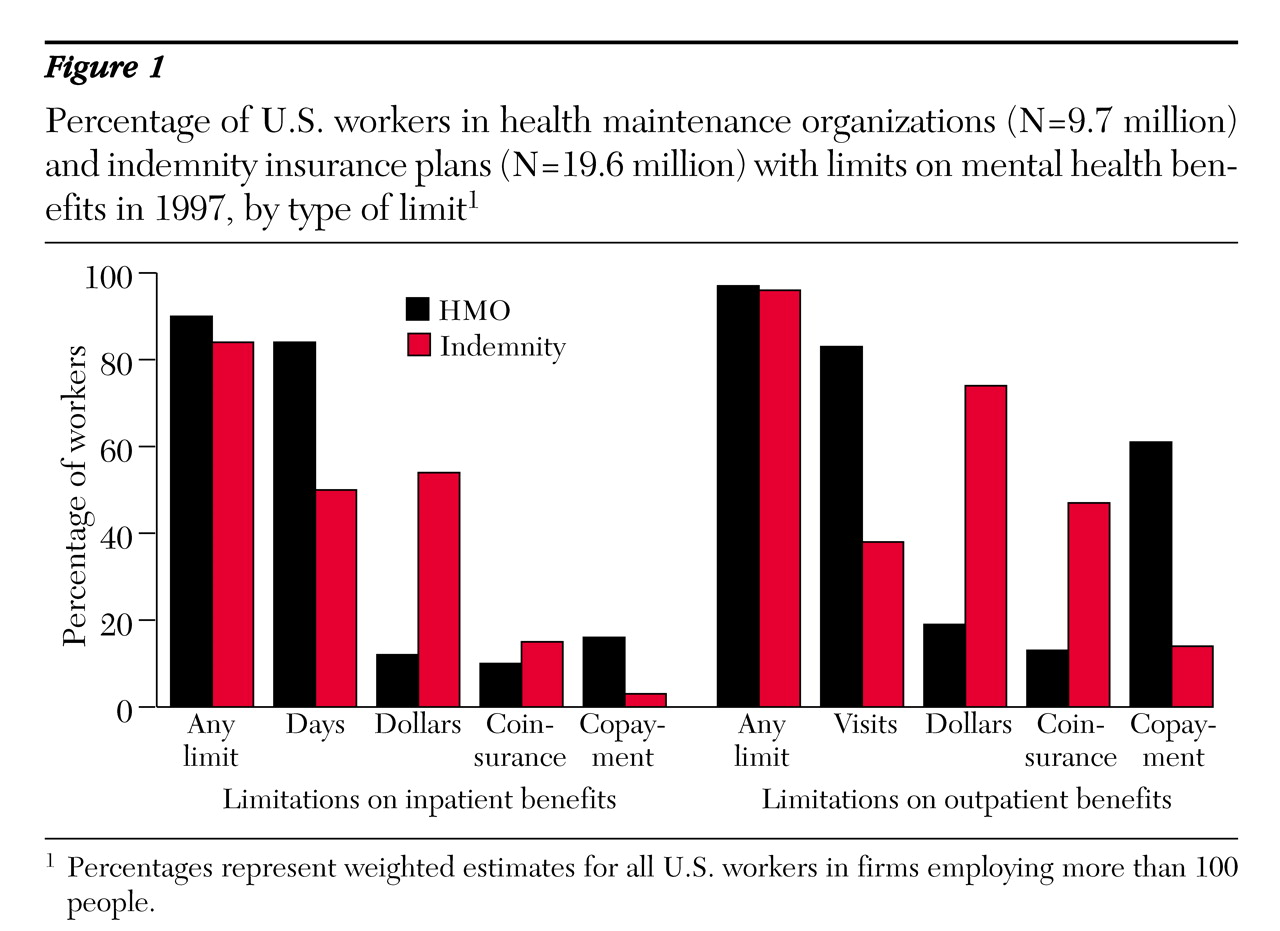

Figure 1 shows the percentage of U.S. workers enrolled in HMOs and indemnity insurance who had limits on their mental health coverage. Although these plan types had similar rates of overall limits on inpatient and outpatient care, the restrictions varied substantially. In HMOs, limits on inpatient days and outpatient visits were the most common restrictions, whereas indemnity plans used dollar caps as the primary cost-containment mechanism. Indemnity plans used coinsurance (payment of a percentage of overall charges after deductibles) as the primary cost-sharing mechanism, while HMOs predominantly used copayments (payment of a set dollar amount per visit or inpatient day).

The results of the survey suggest that although almost all plans offered some mental health coverage in 1997, that coverage was shallow compared with other benefits. Because current mental health parity legislation prohibits only discriminatory dollar limits, it may have a relatively small impact on HMOs, which primarily rely on limits on days and visits rather than on dollar caps to control costs. In the coming years, it will be essential to track benefit packages and to monitor the impact of parity legislation on patients' access to mental health services.