Assertive community treatment teams provide comprehensive crisis, treatment, and rehabilitation services to people with serious mental illnesses in their communities and homes. To ensure flexible, intensive, individualized care, caseloads are shared by multidisciplinary staff and are kept low, at about eight to 15 clients per full-time staff member, (

1,

2). Assertive community treatment requires a balance between activities that build clients' trust and activities that promote behavioral change (

1,

2,

3). Attempts to help clients manage maladaptive behavior can test the relationship, while failure to address problem behaviors can impede successful outcomes (

3,

4).

Because of their illness or because of personal preferences, some clients do not associate difficulties in daily living, such as self-maintenance, or problem behaviors, such as destructiveness, with their illness or with a need for behavioral change (

5). Others plead for help to change behaviors like substance abuse but feel unable to do so on their own (

6). Faced with a client who denies his or her illness, who refuses treatment but presents a risk to self or others, or whose best intentions prove ineffective, assertive community treatment staff must sometimes augment support with active direction or therapeutic limit setting (

1,

2).

Therapeutic limit setting involves activities by the treatment provider to pressure a client to change behavior that is disturbing, dangerous, or destructive or to engage further in treatment. Short of terminating services, limit-setting activities span a continuum of restrictiveness that includes verbal encouragement or admonition ("That behavior keeps getting you into trouble"), contingent support or contracting ("Once you can manage your medications reliably, we'll see about getting you that job"), involvement of others ("You seem to need help managing your money"), informal coercion ("You can enter the hospital voluntarily, or we will have to commit you"), or formal coercion (competency assessment and a commitment hearing) (

7).

Limit-setting activities typically occur within the context of a therapeutic relationship and are intended to help the client (

8). They reflect a respectful, least-restrictive approach, and limit-setting progresses toward more restrictive or coercive interventions only as necessary (

8). A client may perceive even positive coaching by the therapist as coercive (

5); however, the client is most likely to perceive coercion in activities that involve negative pressure, such as threats, force, and loss of liberty, or that appear one-sided (

8,

9,

10,

11).

The literature on coercion in treatment has focused on formal involuntary treatment rather than informal exchanges in community settings (

12,

13). It has defined coercion (versus choice) on a continuum of restrictiveness that incorporates elements of force or control over individuals against their will or without their permission (

3,

9,

12,

14,

15). Theorists have described various levels of pressure such as "friendly persuasion" (

3) or "coerced voluntarism" (

15) without presenting data on their incidence. Despite expressions of concern about the potential ill effects of coercive treatment (

5,

6) and recognition of the need for research in this area (

16), few studies have examined informal pressure or coercion.

The literature on coercion in assertive community treatment has centered on services in Madison, Wisconsin, not because clinicians there are especially coercive but because the community has a long history of testing alternative systems of care. The Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) and the Dane County mental health system are internationally recognized models of community care for people with serious mental illness (

17,

18,

19,

20,

21). Estroff (

22) has described aspects of social control in staff interventions, and Diamond (

3) has acknowledged that assertive efforts to engage clients and promote community functioning can incorporate paternalistic assumptions or coercive motivational strategies. Consumer advocates have expressed concern about potential abuses if assertive community treatment is mandated or linked to job or housing resources. In most cases, limit-setting activities in assertive community treatment may be less coercive because they occur within a long-term treatment relationship that involves the client in treatment planning (

14).

Although studies of therapeutic alliance in case manager-client relationships (

4,

23) have found associations between perceived alliance and clients' outcomes, scant attention has been paid to limit-setting efforts by assertive community treatment case managers (

16). The study reported here used data from a national Veterans Affairs program serving a large population of clients with serious mental illness to document the exercise of informal pressure or coercion in assertive community treatment. The areas explored were the frequency with which a range of limit-setting activities were employed and the relationship of limit-setting activities to clients' characteristics, to the treatment process, and to clients' and case managers' perceptions of the therapeutic alliance.

Methods

This report is based on monitoring data compiled between June 1995 and December 1997 by intensive psychiatric community care teams at 40 VA facilities (

24). The teams provide assertive community treatment services to veterans with serious mental illness who are among the most frequent and long-term users of VA inpatient mental health resources (

25). The services are characterized by high staff-patient ratios, team delivery of individualized community-based services, a practical problem-solving approach, and a high level of continuity of care, similar to standards published for assertive community treatment services (

1,

2).

In comparisons with state-managed programs, intensive psychiatric community care teams have demonstrated good fidelity to the assertive community treatment model (

26). Most teams are composed of master's-level social workers, nurses, rehabilitation specialists, and a part-time psychiatrist, who meet daily to review cases, work collaboratively to provide services for a shared caseload, and are available for off-hours consultation.

Sample

Study participants were 1,564 veterans who had each received intensive psychiatric community care services for six months. Hospitalized veterans with serious mental illness who had 30 or more psychiatric inpatient days in the previous year were eligible for intensive psychiatric community care. At entry, veterans in the program tended to be middle-aged (median age=49 years), male (92 percent), white (71 percent), unmarried (89 percent), and unemployed. About half of the clients (48 percent) had a designated payee and received VA service-connected compensation (57 percent).

Three-fourths of the group (78 percent) had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, and a fourth (24 percent) had both psychiatric and substance use disorders. Clients had a range of clinical diagnoses including schizophrenia (58 percent), schizoaffective disorder (18 percent), bipolar disorder (16 percent), affective disorder (9 percent), alcohol abuse or dependence (19 percent), drug abuse or dependence (10 percent), and personality disorder (4 percent). Clients had extended histories of psychiatric disorder (mean±SD=27±11 years), with a mean±SD of 20±38 hospital admissions. Most (60 percent) had two years or more of cumulative lifetime psychiatric hospitalization.

Baseline clinical measures

Starting at program entry, veterans participated in semiannual face-to-face structured interviews. They reported on their relationships with family members, number of arrests, days of alcohol use (

27), days of drug use (

27), violent behavior, quality of life (

28), and therapeutic alliance (

29,

30). Interviewers rated each client on psychopathology (

31) and global functioning (

32), and clients were given a

DSM-IV diagnosis (

32). Client-family relationships were rated with two 5-point Likert-type questions about the extent of the client's contact with family members; responses ranged from 1, not at all, to 5, at least daily. Violent behavior was scored with four yes-no questions about thoughts, discussions, threats, or actions involving striking or injury.

Case managers completed semiannual structured reviews of clients' progress and of service delivery. They rated limit setting (see below), perceived alliance, and frequency of contact with the client, the client's family members, nonfamily members (conservators, guardians, landlords, residence supervisors, and so forth), and staff at other agencies.

Clients' ratings of the therapeutic alliance were obtained as part of the semiannual follow-up interviews. The alliance was assessed with parallel case manager-client versions of seven 7-point Likert-type questions about the nature of the clinical work relationship, adapted from the Working Alliance Inventory (

29) for use in case management (

30). Responses ranged from 0, never, to 6, always. The frequency of contact between case manager and client was rated with five 6-point questions about typical contact levels during the past six months, with responses ranging from 0, no contact, to 5, three times a week or more.

Therapeutic limit-setting measure

The 25 initial limit-setting items were derived from clinical and evaluation experience with different clinical services and locations. Items exemplified five a priori domains of clinical intervention arrayed along a hypothetical continuum of restrictiveness (

7), from initially making a judgment that a client needs an intervention to implementing the intervention.

The first was verbal confrontation, in which a case manager or team attempts to motivate a client by illustrating the destructive consequences of certain behaviors but without invoking real or threatened behavioral sanctions. The second was behavioral contracting, in which the team and client articulate specific goals for the client to meet, such as reduced substance use, to obtain an identified reinforcer. The third was passive sanctions, in which the team withholds certain aspects of help until the client changes his or her behavior, such as refusing to help a client gain access to a particular program or resource until the client demonstrates that he or she is better able to use and benefit from it.

The fourth intervention domain was invocation of external authorities, in which the team expands the clinical arena to address a problem behavior with a representative payee, a benefits officer, or a criminal justice officer. The fifth was imposition of restrictions, in which the team intervenes directly to establish limits on client behavior, such as through designation of incompetency, appointment of a representative payee, or civil commitment. Response options for this initial trial of the measure reflected three levels of use of the five interventions: 0 indicated rarely or never, 1 sometimes or occasionally, and 2 often or always.

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analysis included a review of descriptive univariate statistics and factor analysis of 25 limit-setting items (SAS PROC FACTOR with promax rotation) to determine whether a priori domains retained coherence as subscales. Item loadings of .40 were used to interpret the rotated factor pattern. Resulting scores were assessed for internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha, interscale correlation, and correlations with clients' characteristics, frequency of case managers' contacts with service providers and others, and perceived alliance. Finally, limit-setting scores were regressed separately on 17 client characteristics, five contact variables, and two perceived-alliance variables, using SAS PROC REG, a standard multiple-regression procedure.

Results

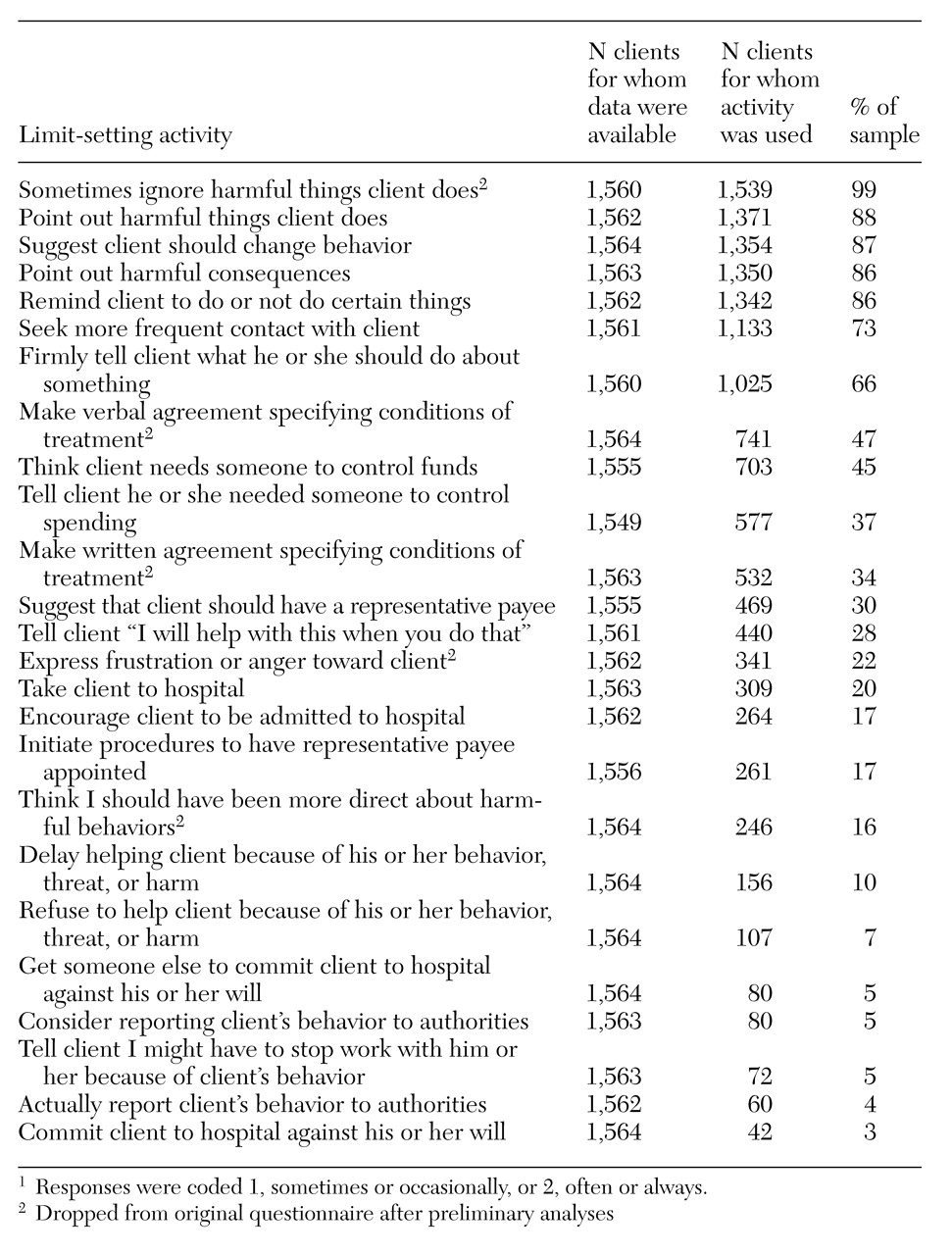

Table 1 presents case managers' reports of how often they used the 25 limit-setting activities listed in the original questionnaire. The activities are listed from most to least frequent. Overall, the frequency of use was inversely related to the restrictiveness of the activity. As discussed below, five items were dropped from the original 25. The frequency of use of the remaining limit-setting activities ranged from 88 percent for pointing out harmful things to 3 percent for committing the client to the hospital. The use of verbal interventions, such as firmly telling clients what they should do, far exceeded the use of strategies restricting service, such as delaying help, or involving other parties, such as initiating use of a representative payee.

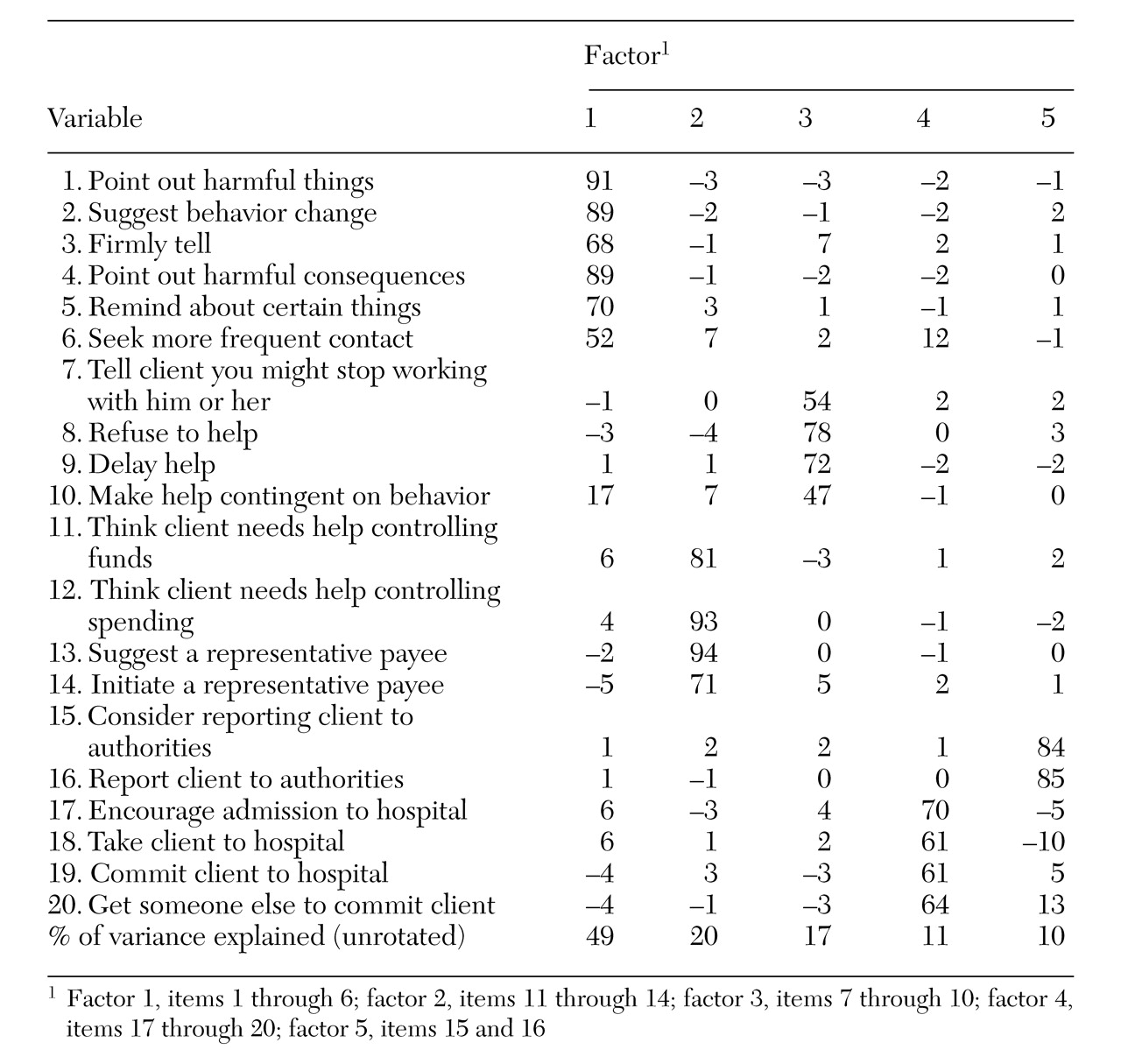

Bivariate correlations of the 25 original limit-setting items ranged from .01 to .82. Five items failed to show a moderate correlation of .40 and hence were excluded. Data for the resulting 20-item scale, the Therapeutic Limit Setting (TLS) scale, form the basis of this report. Factor analysis yielded five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 and marked scree separation. The five factors accounted for at least 10 percent of the variance. They were clearly interpretable and showed satisfactory construct coherence. Items tended to group more by intervention domain than by restrictiveness.

Loadings for TLS items and the variance explained by the five factors are presented in

Table 2. The first factor involved verbal guidance; six items measuring supportive communication loaded on this factor. Money management was the second factor, with four items reflecting a client's inability to manage funds. The third factor was related to contingent withholding, with four items involving the restriction of services to reduce negative behavior. Factor four was enforced hospitalization; four items loaded on this factor, ranging from suggesting hospitalization to committing a client. The fifth factor was invocation of authorities, with two items related to reporting to outside agencies. The variance explained by the five unrotated factors ranged from 10 percent to 49 percent. Item loadings ranged from .47 to .94 across all scales, with a mean of .74.

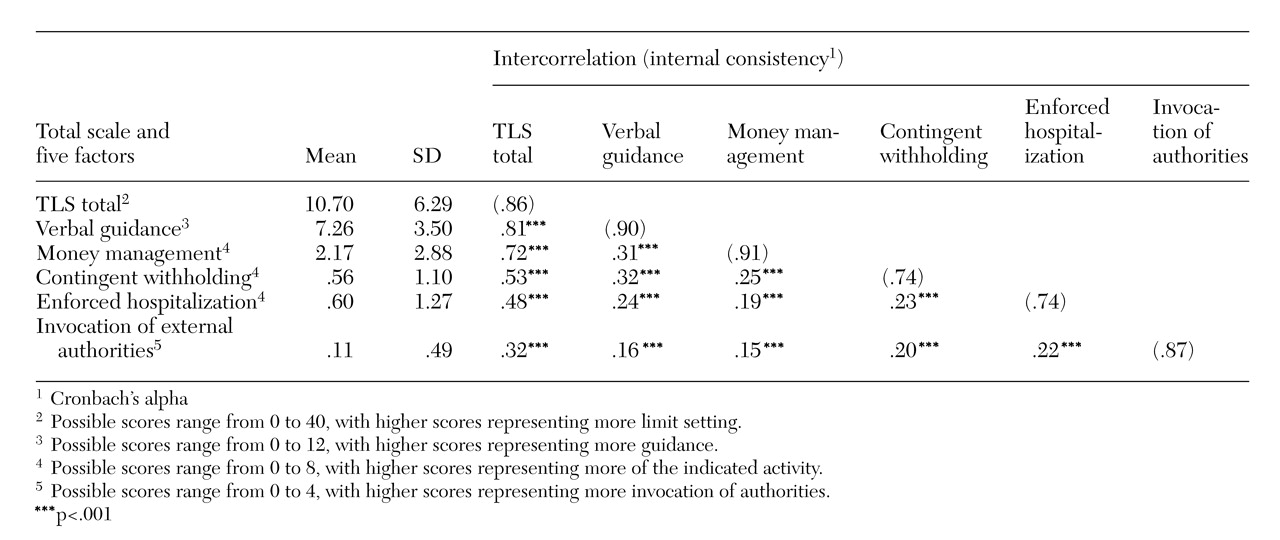

Table 3 presents means, standard deviations, intercorrelations, and internal reliability data (Cronbach's alpha) for the TLS total score and for the five TLS factor scores when used with the 1,564 veterans in the sample. The factor subscore correlations ranged from .32 to .81 with the total TLS score, and from .15 to .32 with each other. Internal consistency was very good for the TLS total score (correlation of .86) and for the five factor subscores (range=.74 to .91; mean=.83).

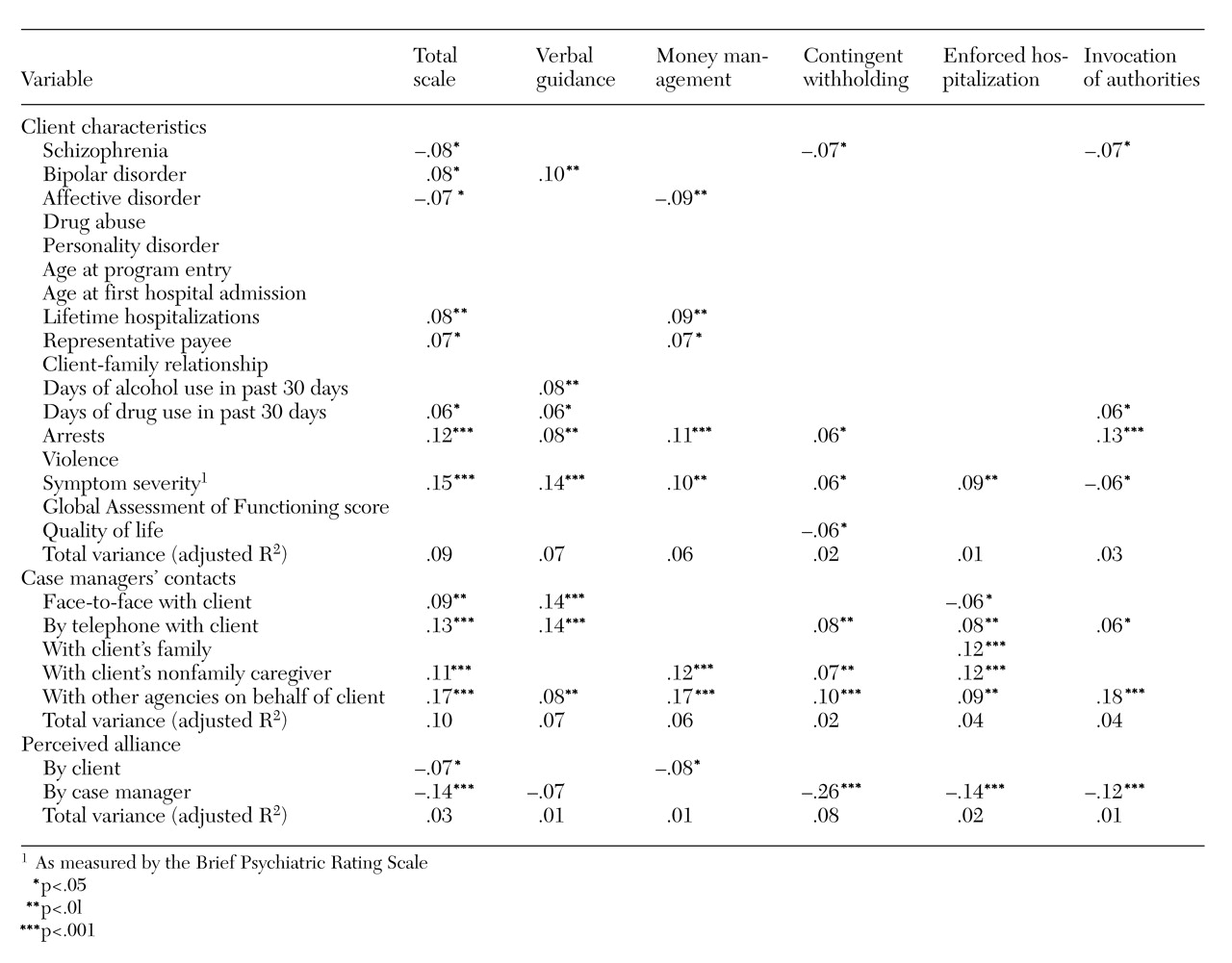

Table 4 presents significant findings for regressions of the five limit-setting variables and the total TLS score on clients' characteristics at program entry, frequency of case managers' contacts at six months, and perceived alliance at six months. Overall, model variance was low, with adjusted R

2 values for the TLS total score of .09 with variables related to clients' characteristics, .10 with variables related to frequency of contact, and .03 with variables related to perceived alliance.

As

Table 4 shows, verbal guidance and money management factors were related most widely to client variables, and the enforced hospitalization factor was related most strongly to variables about contact. Variables most strongly associated with TLS total scores were symptom severity, arrest history, frequency of the case manager's contacts with other agencies or with the client by telephone, and the case manager's rating of perceived alliance with the client. A diagnosis of drug abuse or personality disorder, age, client-family relationship, history of violence, and global functioning were not significantly related to any limit-setting activity.

Limit-setting interventions were more likely to be used with clients who had bipolar disorder, more lifetime hospitalizations, a representative payee, more drug use and arrests, and greater symptom severity. These interventions were less likely to be used with clients who had schizophrenia or an affective disorder. Arrests and symptom severity had the strongest relationships across limit-setting subscores. Hospitalization was exclusively related to symptom severity.

Limit-setting interventions were more likely to be used for clients with whom a team had more direct contact or engagement with nonfamily caregivers or agency staff. Hospitalization was associated with more frequent case manager contacts of all forms, including contact with family members.

Perceptions of alliance at six months, particularly case managers' perceptions, were negatively associated with limit-setting scores. For clients' perceptions of alliance, the negative relationship was associated with money management. For case managers' perceptions of alliance, it affected all areas but money management, and the strongest negative relationship involved contingent withholding of services.

Discussion

These data provide a first look at the use of specific limit-setting activities by assertive community treatment clinicians. Intensive psychiatric community care teams were generally assertive, using various activities to support change and resorting to more restrictive means on the client's behalf when necessary. Although any use of external controls is of concern, the data suggest that the case managers relied on verbal strategies more than on coercive alternatives and used involuntary hospitalization and external authorities with less than 5 percent of the clients.

Intensive psychiatric community care clinicians appeared more likely to employ limit-setting strategies with clients who had greater symptom impairment, who required higher levels of contact with the case manager, and who reported a weaker sense of alliance. Because the data on limit setting, contact, and alliance were collected simultaneously, the direction of causality is uncertain. It is unclear, for example, whether limit setting weakens the sense of trust between participants or whether a stronger alliance lessens the need for limit setting. One might also expect that clients with whom limit setting was used would express greater dissatisfaction with treatment. Further research into the meaning and consequences of clients' ratings of the alliance is indicated.

Several limitations of the study deserve comment. The limit-setting measure was based on retrospective reports of case managers and is vulnerable to self-report error and bias. Because there was no obvious reason for case managers to manipulate reports of more restrictive limit-setting interventions, no attempt was made to validate their reports with information from clients, administrators, or third parties or to assess the measure's interrater reliability. In addition, the data pertain to assertive community treatment services for veterans with serious mental illness and high use of inpatient resources, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations or health care systems. Assessment of services with other client groups and in other treatment settings will be necessary to determine the measure's general utility and validity.

Despite these weaknesses, the study begins to address an issue of considerable clinical and ethical importance with an instrument that has good internal reliability and with a large sample of clients at multiple sites. With additional work on validity and reliability, a limit-setting measure may prove useful for assessing the assertiveness of assertive community treatment teams and comparing community-based services. Future research should address clients' perceptions of coerciveness in limit setting; outpatient commitment, an alternative to hospitalization and incarceration that is gaining popularity among legislators (

13,

33); changes in the use of limit-setting strategies over time; and, most important, the relationship of limit setting to clients' outcomes.

As consumers examine their rights and reactions to mental health care and the legal system redefines what is meant by coercion, mental health service providers and researchers should address the extent and appropriateness of limit-setting activities and their role in effective community-based care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Simpson, Ph.D., for his comments and Richard Baldino, Leslie Cavallaro, and Bernice Zigler for their assistance in managing the data.