Psychotropic medications are one of the fastest-growing and most commonly prescribed classes of medication in the United States (

1). They represent about 9 percent of the prescription drug market (

2). Three of the top ten brand-name prescription drugs are antidepressant medications (

3). Between 1985 and 1994, the number of visits to all physicians during which a psychotropic medication was prescribed increased from 32.7 million to 45.6 million, and the proportion of such visits, as a proportion of all visits, increased significantly, from 5.1 percent to 6.5 percent (

1). Much of this increase was accounted for by a twofold increase in visits for antidepressant medications, although among psychiatrists a 46 percent increase was also noted in visits for antipsychotic medications.

The introduction of new antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs has spurred the increase in psychotropic prescriptions. Although these drugs have advantages over older drugs in respect to side effects and efficacy (

4), their high cost may pose a major limitation to their availability (

5). Many state Medicaid programs, community mental health centers, and managed care companies have limited the use of newer drugs in an attempt to control costs (

5). The National Advisory Mental Health Council (

6) estimated that about 40 percent of persons with severe mental illness do not receive treatment. One reason for this failure to treat is thought to be the high cost of medications (

5).

A recent survey of the pricing structure of newer antidepressant and antipsychotic medications in North America and Europe indicated that the acquisition costs for pharmacists were 1.7 to 2.9 times higher in the United States than in the other countries studied (

5). These findings suggest that a variety of structural factors, including the absence of a national health program, allow for greater profits and concomitantly higher prices for drugs in the United States. Although political and consumer pressures may eventually alter these disparities, prescribers and patients must address the exigencies of the current situation.

Some physicians and patients have long known that considerable cost savings can be realized by splitting higher doses of pills. For example, the

Drug Topics Red Book lists the cost of a hundred Zoloft 100 mg tablets as $228, while the cost of a hundred 50 mg tablets is $221 (

3). Thus when the higher-strength tablet is prescribed and split by the patient, the cost of the 50 mg tablet is cut by half. This pricing pattern is similar for nearly all the newer psychotropic medications and reflects the relative independence of the quantity of the drug from its pricing structure (

7).

Moreover, psychotropic medications generally lend themselves to pill splitting. Unlike some other classes of medication, their clinical actions depend primarily on long-term alterations in neurotransmitter production and receptor sensitivity (

8,

9). Small variations in doses usually are not critical to effectiveness.

Methods

To assess the feasibility and potential cost savings from pill splitting, we identified all new psychotropic medications that were among the top 200 brand-name prescription drugs, according to the

1998 Drug Topics Red Book, that had strengths that could be halved and that were in noncapsule form (

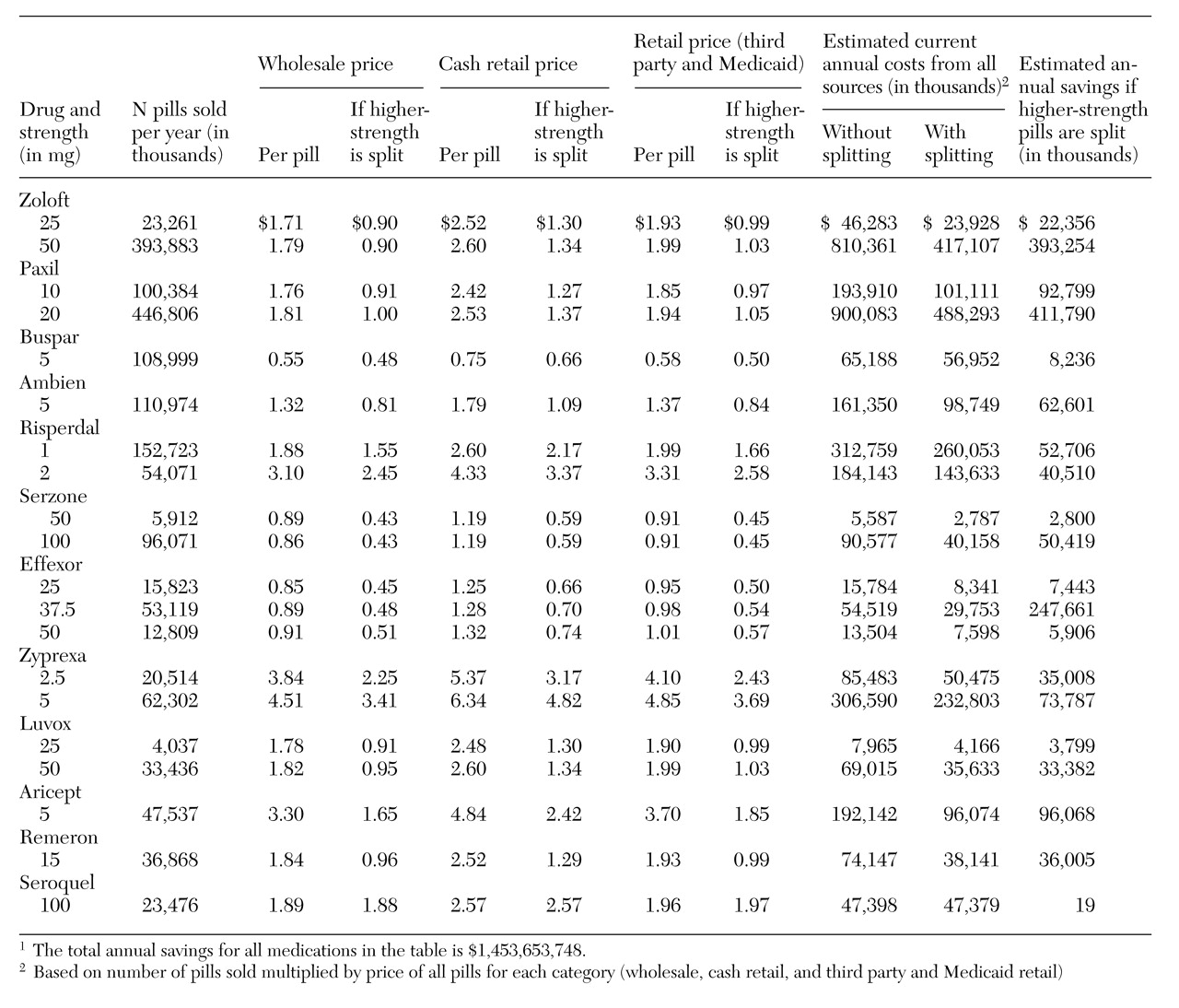

3). We identified a total of ten drugs, which are listed in

Table 1 along with two new psychotropic drugs that were introduced in 1997, Remeron and Seroquel.

Thus a total of 12 drugs that had been on the market for all of 1998 were examined. Manufacturers' data indicated that 54 percent of all pills sold were at strengths that allowed for pill splitting. We did not include the new sustained-release form of Wellbutrin, although the exposed area of the pill after it is split is so small that blood levels of the drug would probably not be appreciably altered.

The calculation of drug costs must include a variety of factors such as discounting of official wholesale (Red Book) costs and use of third-party reimbursements for which precise data are not always accessible. However, it is possible to make a reasonable estimate of prescription costs that illustrates the advantages of pill splitting. Sites of prescription dispensing were divided into two categories. In the first category are nonfederal hospitals, federal facilities, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and clinics. In the second category are chain stores, independent pharmacies, food stores, and long-term-care facilities.

The proportion of all prescriptions dispensed at sites in the first category ranged from 6 to 18 percent for the 12 psychotropic medications. Between 82 and 94 percent were dispensed at sites in the second category (

10). For the cost of medications dispensed at sites in the first category, we used the wholesaler's actual invoice costs for each strength of medication (

10). For medications dispensed at sites in the second category, we calculated costs for prescriptions covered by third-party payments and Medicaid based on 90 percent of the

Red Book charges listed for each strength of medication. For prescriptions without third-party payment, we estimated costs for each strength to be 117.7 percent of their

Red Book cost. These parameters were based on our survey of nine large pharmacies in New York City. The percentage of prescriptions without third-party payment ranged from 10 to 34 percent for the 12 medications.

Results

As can be seen in the table, if all eligible prescriptions were used in split dosages, consumers could save about $1.45 billion annually. If a half or a fourth of eligible prescriptions used split dosages, savings of $725 million and $363 million, respectively, could be achieved. If pill splitting was restricted to only the two most widely prescribed psychotropic drugs in tablet form, Zoloft and Paxil, pill splitting could still realize a savings of as much as $920 million dollars.

Discussion and conclusions

Given total retail and wholesale sales of approximately $12 billion for all strengths of the drugs studied, pill splitting could reduce consumer costs by more than 10 percent. Such savings would be a bonanza not only to consumers but also to state Medicaid programs, community health centers, and managed care companies that have been trying to contain costs. Moreover, this approach would presumably allow for wider use of the newer psychotropic medications.

Of course, some consumers with no social support and with poor eyesight, diminished cognition, disorganized thinking, or impaired dexterity would not be ideal candidates for splitting pills. Patients who are reluctant to use a knife might be pleased to discover that an easy-to-use pill-splitter can be purchased in a pharmacy for under $4. Older patients commonly report that half-pills are much easier to swallow.

Even when patients wish to split their pills, several potential impediments exist. Many pills are not scored in their higher strengths, and some patients feel uncomfortable and imprecise in dividing such pills, even with a pill splitter. This fear is exacerbated by pharmacists who are often unwilling to fill prescriptions that call for half-dosages of unscored medication. Finally, patients should be cautioned that because of the coating of Zyprexa, split tablets must be used within seven days.

Pill splitting offers an innovative, practical method for greatly reducing the cost of psychotropic medications. To further the use of pill splitting, we recommend that manufacturers be compelled to score all strengths of medications; that pharmacists be required to fill all prescriptions for split doses, regardless of whether the pills are scored; and that health care programs provide incentives to pharmacists to split medication for outpatients and inpatients, perhaps allowing them, say, a 10 percent surcharge for pill splitting.