Rapid changes in the delivery of health care in recent years have led to increased emphasis on evaluating the quality of care. Quality evaluation on a large scale is extremely difficult, however (

1). The Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) has become the standard tool for comparing health plans (

2,

3). Even though other measures of mental health quality have recently been considered for use in HEDIS (

4), this tool employs only a single measure of the quality of mental health services: the percentage of patients hospitalized for affective disorder who receive outpatient services within 30 days of discharge (

2,

3).

In response to pressure to reduce the costs of health care, both the private sector and VA have undergone significant changes. The private sector has developed various cost-containment mechanisms, such as utilization review, case management, exclusive contracting arrangements with selected providers, and risk sharing (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11). In October 1995 VA implemented a major reorganization that produced similar results (

12). The VA system was reorganized into 22 distinct networks, each responsible for the health care needs of a geographically defined population. A major goal was to shift the focus of care away from acute inpatient care and toward ambulatory and primary care (

13). National performance standards were implemented to encourage this change. These management changes have had significant effects on mental health utilization and costs in both systems (

12,

14,

15).

In the study reported here, we examined the impact of changes in the organization and delivery of mental health care on the quality of mental health care. The Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System includes a variety of quality measures, which are constructed from readily available administrative databases. Using these measures, we compared the quality of mental health care in VA between 1993 and 1997 and in a sample of privately insured individuals between 1993 and 1995. Because comprehensive assessment of quality must involve trend analysis in addition to assessment of cross-sectional performance, we included 1997 VA data to compare how the systems have changed in response to the introduction of managed care mechanisms.

Methods

Sources of data

VA data for this study came from two national data files that include information from 172 VA medical centers. Patients admitted to the hospital for a psychiatric or substance abuse disorder were identified using the patient treatment file, a discharge abstract of all completed episodes of inpatient care in the VA system. Data on outpatient service use were collected from the outpatient file. Data are available from fiscal year 1993, which began October 1, 1992, to fiscal year 1997, which ended September 30, 1997.

Data on privately insured individuals come from MEDSTAT's MarketScan database, which contains claims information for a national sample of more than seven million covered lives between 1993 to 1995. The claims data, which cover employees and retirees of large corporations and their dependents, were collected from more than 200 different insurance plans, including Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans and third-party administrators.

For both systems, we identified patients admitted to the hospital with a psychiatric or substance use disorder and discharged in the first half of the year. In the VA system behavioral health inpatients were identified by the bed section from which they were discharged. Privately insured behavioral health patients were identified by the primary diagnosis associated with the admission, usually the discharge diagnosis. In both systems, these patients were tracked for 180 days after discharge, and data on both inpatient readmission and outpatient service delivery were recorded.

Quality measures

We defined ten measures to evaluate the quality of mental health care. The inpatient measures include the length of the index hospital stay, the number of days to the first readmission after discharge, and the percentage of patients who were readmitted within 14, 30, or 180 days after discharge. Readmission measures have been shown to be significantly related to clinical outcome (

16).

Outpatient follow-up measures included the percentage of patients who had an outpatient visit within 30 or 180 days after discharge, the number of days to the first outpatient visit, the number of outpatient visits in the 180 days after discharge, and a measure of continuity of care. The continuity measure was defined as the number of two-month periods with two or more outpatient visits in the six months after discharge. These measures have also been shown to be significantly related to some clinical outcomes (

16).

Patient characteristics

In computing the quality measures described above, we controlled for a number of patient characteristics. We were able to control for age and gender of the patient across both systems, but were unable to control for ethnicity in the privately insured sample because insurance organizations are prohibited from collecting this information. We also could not control for income, disability, or homelessness, all of which are likely to be very different between these two systems.

Besides controlling for demographic characteristics, we assigned each patient to one of five diagnostic groups: schizophrenia (ICD-9 codes 295.00 to 295.99), major depression-bipolar disorder (296.00 to 296.99), substance use (291.00, 292.00, and 303.00 to 305.99), mild-moderate depression (300.40, 300.50, 301.10, 309.10, 309.90, and 311.00), and other psychiatric disorders (290.00 to 312.99 not elsewhere assigned).

The diagnostic group to which a patient was assigned was based on the ICD-9 code representing the primary diagnosis of the index admission. The diagnostic categories are mutually exclusive. Of the diagnoses included in "other psychiatric disorders," the most common were adjustment reaction (25.8 percent for the private sector and 7.3 percent for VA), neurotic disorders (19.3 percent for the private sector and 3.9 percent for VA), and other nonorganic psychoses (13.5 percent for the private sector and 3.9 percent for VA).

Finally, among VA patients, we controlled for whether the patient's illness was connected to military service. Veterans with service-connected disorders have more comprehensive coverage than those whose illness is not connected to service.

Statistical analysis

Analysis proceeded in several steps. For both the VA and privately insured samples, we first identified inpatients discharged in the first half of each year with a behavioral health primary diagnosis. Next we abstracted service utilization data, which we used to construct the quality measures described above. We then calculated adjusted means for each of these measures for both the VA and the privately insured samples, controlling for year, patient age, gender, diagnostic category, whether the patient had dual diagnoses, and, for VA patients only, whether the disorder was service connected.

We ran separate models for the VA and the privately insured samples to control for a different set of patient characteristics in each sample. We used the SAS general linear models procedure (

17), with the least-square means option, to calculate the means of our measures. To investigate the interaction of year with patient characteristics, we conducted a series of two-way analyses of covariance in which we looked at differences across the years in the effects of patient characteristics on the dependent variables. (A more detailed description of the procedures is available from the authors.)

Results

Sample characteristics

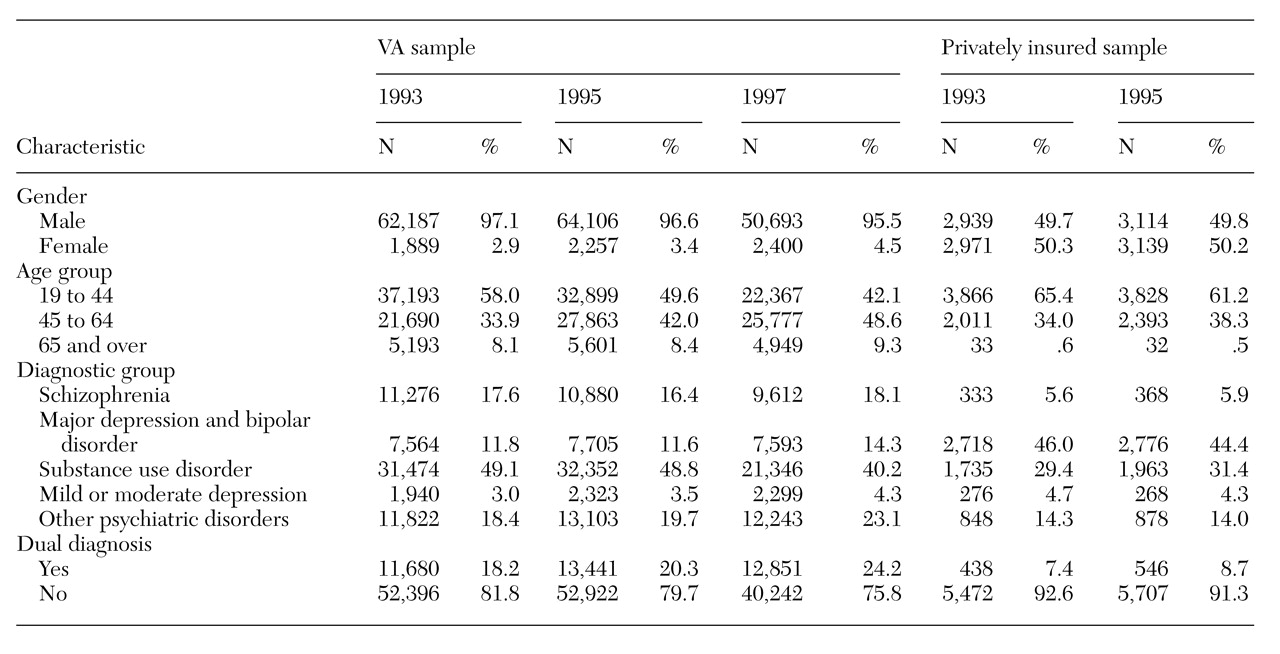

Table 1 shows sample characteristics. The VA sample was overwhelmingly male, whereas the private-sector sample was more evenly divided across gender and was younger than the VA group. A considerably higher fraction of VA patients were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, and a much lower fraction were diagnosed as having major depression or bipolar disorder. Finally, VA patients were much more likely than privately insured patients to have a dual diagnosis.

These results illustrate the significant differences between the two populations. Individuals eligible for VA services are poor and often homeless (

18) and unemployed (

6). We expected such a population to be sicker on average than a group of employed individuals with private health insurance, but we could not control for all of the differences between these populations because data on homelessness, income, and disability are not available from the MarketScan database.

Inpatient measures

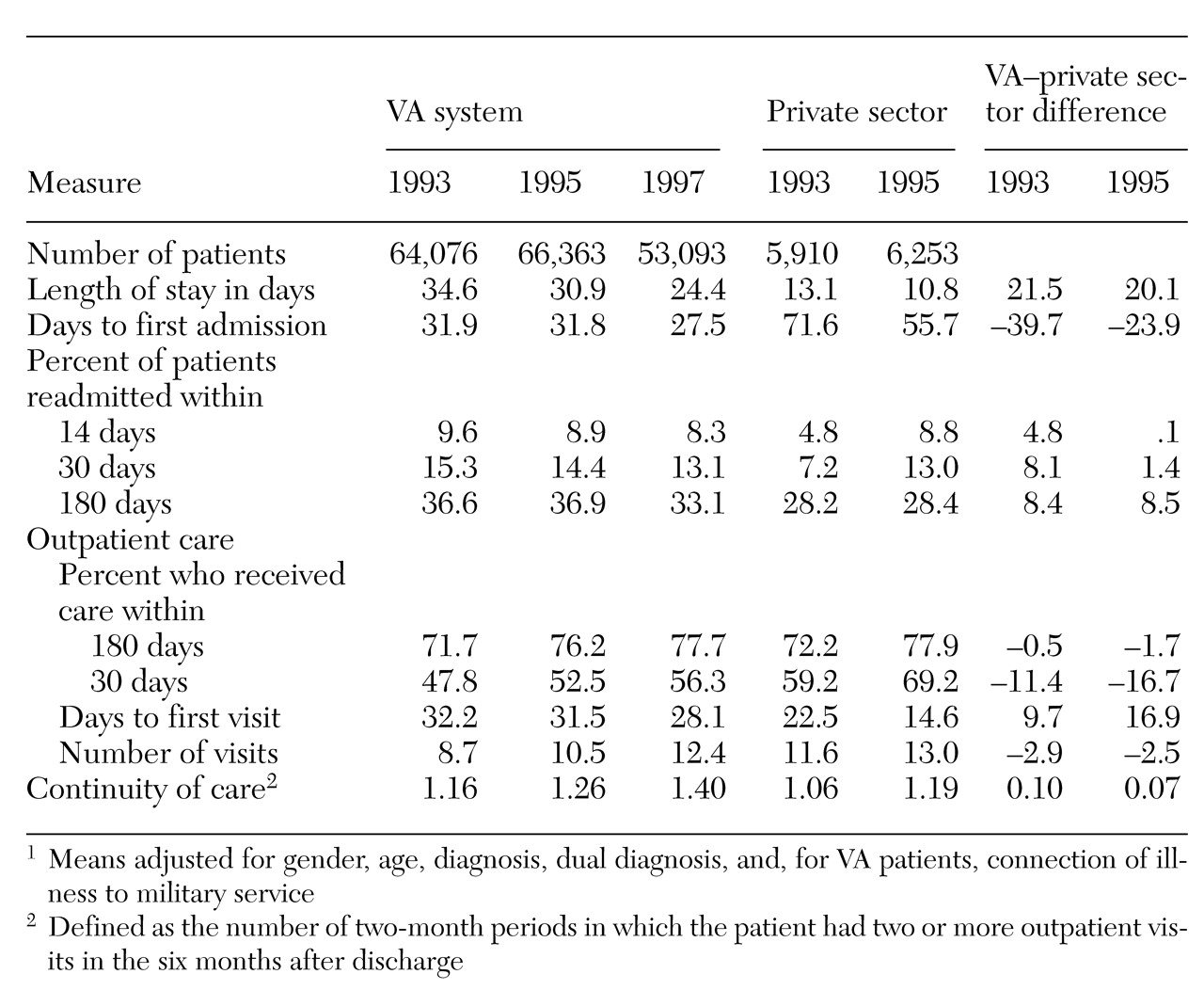

Table 2 shows the adjusted means for the quality measures for the VA and private-sector systems and the difference between the two systems on these measures. We cannot report statistical tests of the differences across service systems because these models were run separately for each system and could not legitimately be merged.

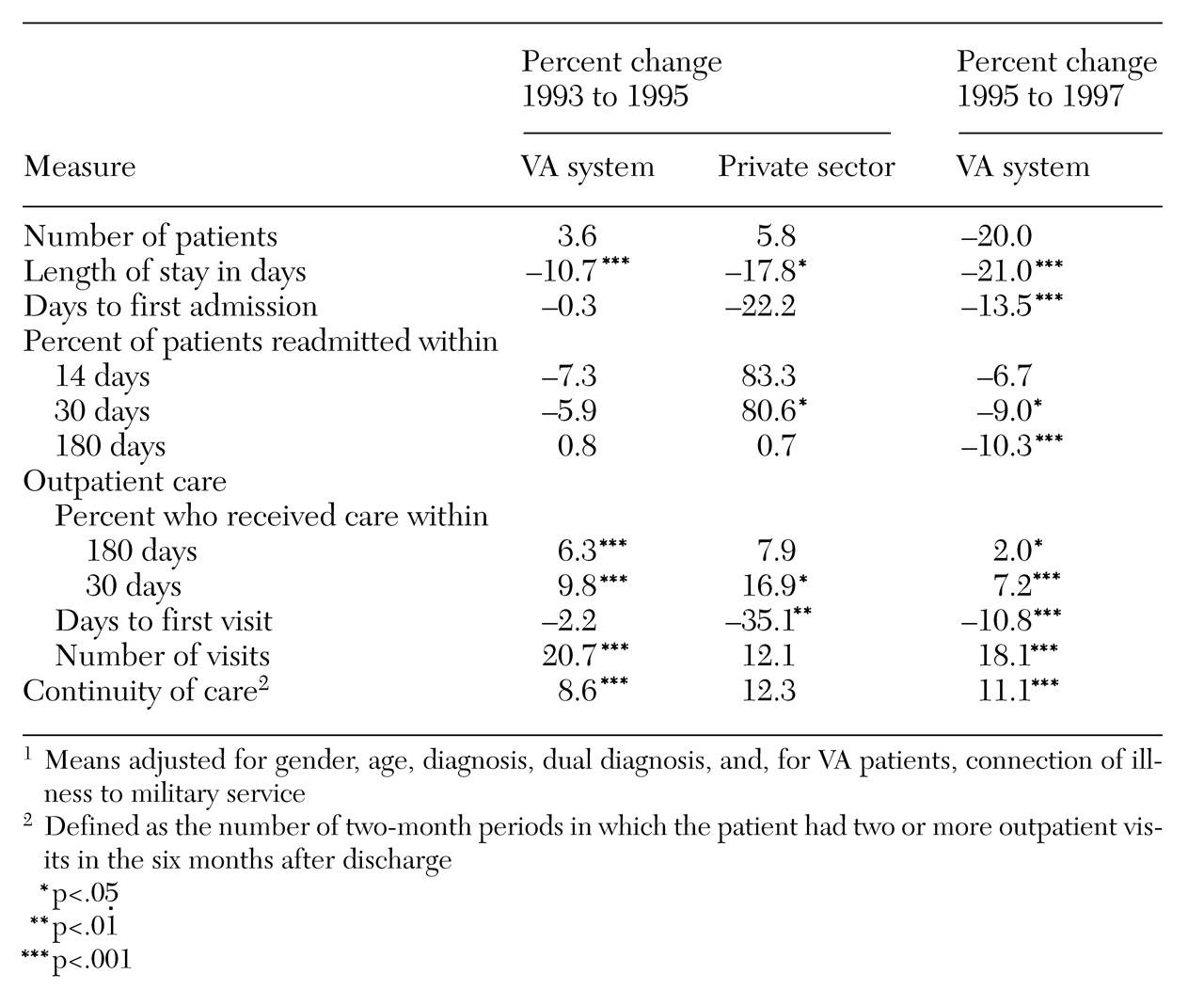

Table 3 presents changes over time within each system, along with data on significant differences.

As

Table 2 shows, in 1993 the length of stay was substantially higher in the VA sample than in the privately insured sample, 34.6 days versus 13.1 days. Length of stay declined over time in both systems, although the decline was much faster in the private sector than in the VA system between 1993 and 1995. After 1995, length of stay fell much faster in VA, with the rate of decline exceeding that seen earlier in the privately insured sample.

Rates of readmission within 180 days of discharge were higher in the VA sample in 1993 (36.6 percent compared with 28.2 percent), but the differences were smaller for readmission rates within 30 or 14 days of discharge. In the VA system, long-term readmission rates stayed roughly the same, and short-term readmission rates declined slightly. In the privately insured sample, however, short-term readmission rates increased dramatically—more than 80 percent between 1993 and 1995. As a result, the gap between the VA system and the private sector in readmission rates declined over time. We see a similar pattern in the number of days to the first readmission.

Outpatient measures

In 1993 the percentage of patients receiving outpatient care within 180 days of discharge was fairly high and virtually the same in both systems (71.7 percent for VA and 72.2 percent for the private sector). Patients in the private sector received outpatient care sooner, however. The percentage of patients receiving outpatient care within 30 days of discharge was higher for privately insured patients (59.2 percent versus 47.8 percent), and the number of days to the first outpatient visit was lower (22.5 versus 32.2). These measures improved over time in both service systems, but much more so in the privately insured sample than in the VA sample. Privately insured patients also had a slightly higher number of visits than VA patients in the 180 days after discharge.

The VA outperformed the private sector on one outpatient measure: continuity of care. In 1993 VA patients averaged 1.16 two-month periods with two or more outpatient visits in the six months after discharge, compared with 1.06 in the privately insured sample. This difference declined over time, however, as the continuity measure increased faster for the privately insured sample than for the VA sample.

Differences by diagnostic group

We also stratified the above analyses by diagnostic group. (Data are available from the authors.) In both service systems, patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia or major depression-bipolar disorder had longer lengths of stay and higher readmission rates. Patients diagnosed as having a substance use disorder had the lowest readmission rates, especially short term. Readmission rates generally declined over time, although slightly less so for patients with schizophrenia. Because these patients are sicker, they may be less likely to improve on the measures over time.

Patients with major depression or bipolar disorder had higher rates for outpatient visits within 30 and 180 days after discharge, more outpatient visits, and higher continuity-of-care scores compared with other diagnostic groups. Patients with a substance use disorder had the lowest outpatient admission rates, fewest outpatient visits, and lowest continuity scores, although these measures increased more over time than for other diagnostic groups.

Comparing the two systems across diagnostic groups, the private sector outperformed VA to a modest degree on many of the quality measures. Relative to levels in the private sector, inpatient readmission rates are lowest in the VA system for patients diagnosed as having other psychiatric disorders. VA patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia had lower readmission rates than the private-sector patients in 1993, but relatively high rates in 1995. Patients with major depression-bipolar disorder or mild-moderate depression had the highest readmission rates relative to the private sector. VA patients diagnosed as having a substance use disorder came the closest to their private-sector counterparts on the outpatient measures.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the performance of VA and private-sector systems on ten measures of quality of mental health care, adjusted for age and gender but not for other potentially confounding factors. We found that, overall, private-sector mental health inpatients had shorter lengths of stay, more days to the next inpatient readmission, and lower readmission rates within 14, 30, or 180 days of discharge compared with VA mental health inpatients. Although VA patients had higher continuity-of-care scores, moderately higher proportions of private-sector patients had an outpatient visit within 30 and 180 days after discharge. Private-sector patients also had fewer days to the first outpatient visit and more outpatient visits in the six months after discharge. Readmission rates increased substantially over time for private-sector patients, however, whereas these measures fell in the VA sample. The proportion of patients receiving outpatient care within six months of discharge improved over time for both populations.

When we stratified the analysis by diagnostic group, we found that the private sector outperformed VA to a modest degree for each of the diagnostic groups. The VA quality measures were highest relative to the private sector in treating substance use and other psychiatric disorders. The difference between the service systems was largest for patients in the depression diagnostic groups. We might have expected VA to do relatively well in treating the more severe diagnostic groups, as it has more comprehensive coverage. However, the results did not bear out this expectation.

One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that private-sector patients who are more severely ill may have exhausted their plan benefits. In that case, our claims database would not have captured services used after the claims were no longer paid. The difference in readmission rates may also be biased downward for this reason as the VA system does not impose such benefit limits. In addition, patients in the private sector must follow very specific rules in order for claims to be considered valid by insurance companies. Some claims may not be reimbursed—and therefore would not show up in the database—if these rules are not followed.

Unmeasured differences in the types of patients treated in these service systems are likely to explain some of the observed differences in quality measures between VA and the private sector. In contrast to private-sector patients, VA patients are poor, with an average income of $10,204 (

5). They are typically disabled (

6), and 35 percent are homeless (

18). Further, they generally have more severe disorders than patients in the privately insured sector.

Other studies have found that low-income and homeless patients have longer lengths of stay than other patients (

19). A study of hospital discharge data from hospitals in New York City between 1992 and 1993 found that lengths of stay for homeless mentally ill patients averaged 36.2 days (

20), just slightly more than the average length of stay of 34.6 days for VA patients in 1993. In addition, poor, disabled, or homeless patients might be more likely to develop complications requiring readmission or be less likely to show up for outpatient follow-up appointments.

This study demonstrates some of the methodological challenges of assessing quality across health care systems. One can argue that low readmission rates or high proportions of discharged inpatients receiving outpatient follow-up care are indications of quality health care. However, low readmission rates may also be a result of restrictive readmission criteria or exhausted plan benefits, and a high proportion of inpatients receiving outpatient care within 30 days of discharge might suggest that patients were pushed out of an inpatient setting to outpatient care too soon. Without detailed information on procedures and outcomes, it is difficult to determine overall quality using administrative data. Another approach, using detailed survey data to compare quality across systems, is feasible (

21). It is more costly, however, and relies on much smaller and possibly unrepresentative sample sizes.

Despite the differences observed in our quality measures between VA and private-sector patients—perhaps partly attributable to differences in severity of illness and failure to capture all private-sector service use—it is notable that the systems were roughly similar on most measures. It is also of interest that inpatient readmission rates increased substantially in the private sector while they declined in the VA system, which may reveal significant differences in how the quality of care is changing over time in these two systems.

Do the substantial limitations of our quality measures and the differences in the populations served in the two systems overshadow the usefulness of doing these analyses? In addressing this question, we consider the following thought experiment. Suppose the federal government was considering whether to discontinue VA mental health services, and crucial decision makers asked if data existed to support their decision. We feel that the data from this study, although flawed, would be more useful than no data at all. These data could reasonably support the statement that the VA does less well than the private sector, but that the differences are likely explained by differences in patient characteristics, and that VA performance is therefore roughly equivalent to that of the private sector. If in the VA system, for example, only 10 percent of patients made an outpatient visit in the 30 days following discharge and 40 percent were readmitted within 14 days of discharge, one might come to a more negative conclusion.

This study is useful in that it presents a rare comparison of the operation of two very different sectors of the U.S. health care system. In addition, it sheds light on how changes in the delivery of mental health services in the VA and private-sector systems may have affected the quality of care. This study is also useful in pointing out both the difficulties and the importance of comparing quality across service systems. As government health care systems are increasingly compared with private-sector firms, designing measures for comparing quality across service delivery systems, and for adjusting for differences in patient populations, should be a major priority for health services researchers.