Today most behavioral health care in the United States is managed by specialized managed behavioral health care organizations under managed behavioral health carve-out contracts. Considerable research has been conducted on the effect of this type of organization on the costs and quality of care. However, less research has focused on the patterns of care under these contracts.

In this report, we present information obtained from a large managed behavioral health organization on the distribution of insurance payments for behavioral health care services for a large sample of employment-based contracts. The behavioral health organization managed the care under these contracts but did not assume financial risk.

The data reflect the use of behavioral health services in calendar year 1996 under 911 contracts with 1,667,015 covered lives. Behavioral health services were identified by the primary International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code on the billing record. Payments were for services only and did not cover psychotropic medications.

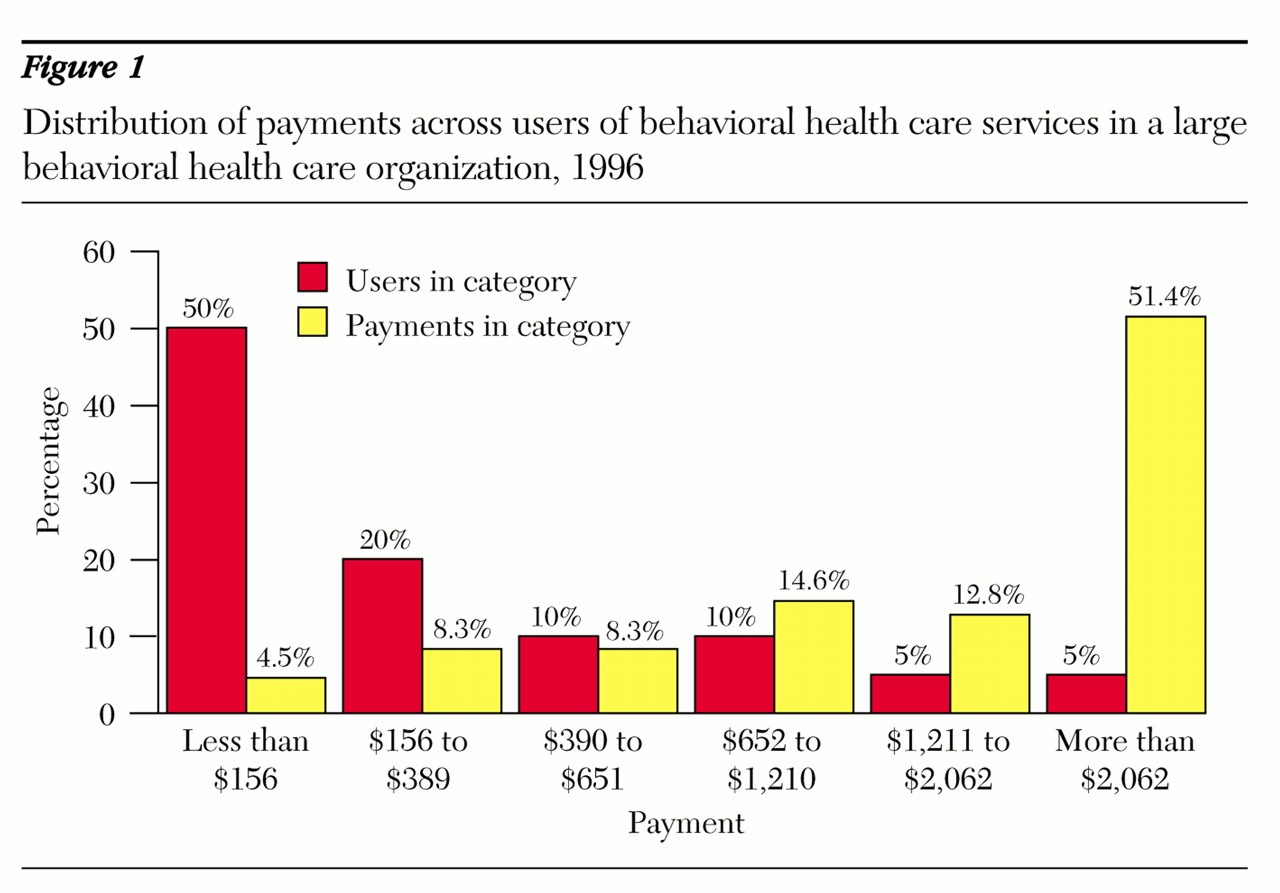

Figure 1 presents the results of the analysis. It shows that payments made in 1996 on behalf of the majority of the users were very low—less than $156 per year for 50 percent of those who used behavioral health services. A small proportion of service users—5 percent—accounted for slightly more than 50 percent of plan payments.

It is worth noting that these payments for behavioral health care mimic the patterns of payments for physical health care, even though the total payments differ markedly. For example, among Medicare beneficiaries who had some Medicare payments in 1997, 36 percent had payments that totaled less than $500 per year. These payments accounted for only 1.2 percent of all Medicare expenditures. Six percent of beneficiaries had payments over $25,000, but they accounted for more than 50 percent of overall Medicare expenditures (

1).

This distribution is a result of several factors. Some people are referred for evaluation and do not need subsequent care, which contributes to low average yearly payments for those patients. Of more importance is the fact that although many people in this insured population are not very sick, some are very sick and require intensive services such as hospitalization. It is likely that these very sick patients account for a significant number of those who are in the top 5 percent of users.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant MH-56925 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Magellan Behavioral Health for providing these data, in particular Keith Roberts, Loretta Sefovic, Dave Dressman, and Ann Montgomery. They also thank Ying Xu for programming assistance.