The problem of homelessness among people with serious mental illness has received significant attention since the early 1980s (

1,

2) and continues to be of great concern as the trend of closing and downsizing state hospitals continues. The risk of homelessness among individuals with serious mental illness was found to be ten to 20 times higher than in the general population (

3). Studies show that 4 to 36 percent of state hospital patients experience homelessness either before or after their state hospital stay (

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10). In addition to active psychiatric symptoms, substance dependence, poverty, and scarce instrumental supports from family and significant others contribute to difficulty in acquiring and maintaining housing, particularly in tight housing markets (

11,

12,

13,

14).

The inability of the community-based mental health system to deliver coordinated services required to meet the multiple needs of homeless persons with serious mental illness has figured prominently as a potential contributing factor (

15). According to Okin (

16), community-based services have been "underfunded, incomplete, fragmented, poorly monitored, and inaccessible to many patients." This situation is partly the result of states' inability to shift expenditures from the state hospital to community programs while running both systems at the same time (

17).

The closing of Philadelphia State Hospital in 1990 provided an unusual opportunity to examine the extent of homelessness in a seriously mentally ill population in an area that had a well-funded community-based mental health system. The hospital was a 500-bed facility, serving 1.6 million people in the Philadelphia area. Its closing resulted in an agreement that allowed $50 million dollars in funds received by the hospital annually to be transferred to local community programs. The enriched community-based system consisted of 60 extended acute care beds in two community hospitals and approximately 1,750 residential beds in facilities providing transitional and long-term housing. In addition, an intensive case management program was added to an array of ambulatory services provided by 12 community mental health centers (

18).

A previous study of 321 long-stay patients discharged from Philadelphia State Hospital showed only a 2 percent rate of homelessness in the three years after discharge (

19). Most of the discharged long-stay patients lived in supported residential accommodations where community treatment teams managed their care. The study reported here focused on a group of acute patients with serious mental illness who had been hospitalized in a general hospital and then referred to an extended acute care facility. This group of patients was selected because they represent one of the most challenging groups for a community-based mental health system in which long-term psychiatric beds are no longer available.

The rate of homelessness was examined. The level and type of outpatient psychiatric treatment used by persons who became homeless were compared with the level and type used by those who maintained stable housing. In addition, monthly mental health service use by the homeless subjects before and after their initial episode of homelessness was examined to gain insight into their pattern of mental health service use.

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 438 individuals who had been hospitalized for acute psychiatric care in a community hospital and referred to an extended acute care facility between July 1, 1990, and June 30, 1992. Their mean±SD length of stay in the community hospital was 55±24.2 days. The sample constituted 83 percent of all referrals to the facility during the study period. Those excluded from the study had missing or incomplete service data; no statistically significant differences were found in sociodemographic characteristics between the excluded individuals and the study subjects.

At the end of 1992, Philadelphia's public shelter system had a census of 2,490 persons, including children (

20). Approximately 44,000 people used the shelter system between 1990 and 1992.

Measures and data sources

A homeless episode was defined as admission to a public shelter between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 1993. An administrative data file from the County Office of Mental Health consisting of referrals from general hospitals to extended care beds was used to select the sample. Shelter admission data were obtained from an administrative database maintained by the Philadelphia Office of Emergency Shelter and Services, which contained information on individuals who were interviewed on their first shelter admission, including the date of the interview and sociodemographic variables (

20). Client identifiers were used to link shelter admission to service files. The linking and integration of data files have been described in detail elsewhere (

21).

Sociodemographic data and information about Medicaid eligibility status were obtained from Medicaid claims records. The hospital discharge diagnosis, derived from the Medicaid claims record, was used to identify diagnoses of psychiatric and substance use disorders. Data on receipt of psychiatric, substance abuse, and health care services were obtained from Medicaid claims files. The county reporting system provided information on residential care. Two measures of service use were employed: the percentage of subjects who had a service contact and the intensity of service use, measured by average annual utilization rates per user. Service units were measured in days for inpatient and residential care and in contacts or visits for outpatient services.

In addition, the length of the shelter stay and the number of admissions in the year after the initial shelter admission were calculated using information from the database of the Office of Emergency Shelter and Services, which tracked admission and discharge at an individual level.

Analysis

Sociodemographic and service use characteristics of seriously mentally ill subjects who experienced a homeless episode were compared with those of seriously mentally ill subjects who did not using chi square tests of significance for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for nonparametric statistical analyses. To explain the effect of outpatient service use on homelessness, a multivariate logit model was employed, using shelter admission as the dependent variable (coded 0 for no admission and 1 for admission) regressed against a host of demographic and service history variables. The percentage of subjects who were mental health service users before and after the homeless episode was examined monthly to better understand the mental health care patterns related to the episodes of homelessness.

Results

Characteristics of homeless subjects

A homeless episode was experienced by 104 of the 438 subjects (24 percent) during the four-year study period; approximately 13 percent experienced their first homeless episode before referral to the extended acute care facility and 11 percent after referral.

Data on length of stay in shelters during the year after the initial homeless episode was available for one-third of the homeless subjects (N= 37). The mean±SD length of stay was 14.2±31.6 days for the initial admission (median, one day). The mean±SD number of admissions during the year after the initial shelter admission was 2.4±3.5 (median, one admission). The mean±SD number of days homeless during that year was 21.5±43.1 days (median, four days). Although a large percentage of the subjects were admitted to a shelter, the median length of stay was less than a week. However, the findings about shelter stays should be interpreted cautiously, because of potential differences in retention policies between shelters.

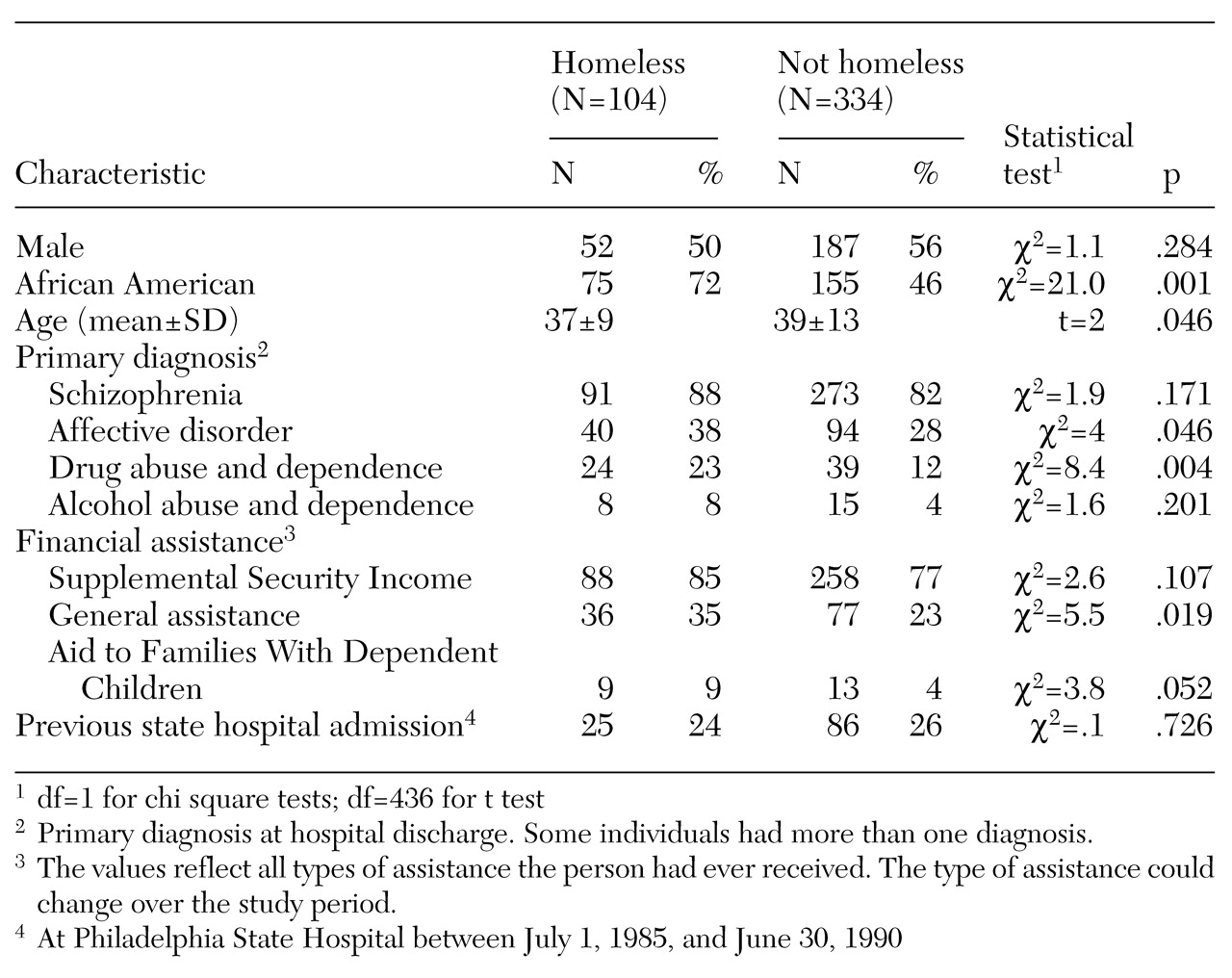

Table 1 presents data on the sociodemographic characteristics of the 104 homeless subjects and the 334 subjects who did not experience homelessness. As other studies have found, the homeless subjects were younger on average (37 years versus 39 years) and more likely to be African American (72 percent versus 46 percent). In addition, a significantly larger percentage of the homeless subjects received state income assistance—that is, general assistance (35 percent versus 23 percent). Homeless subjects were significantly more likely to have affective disorders (38 percent versus 28 percent) and drug use disorders (23 percent versus 12 percent).

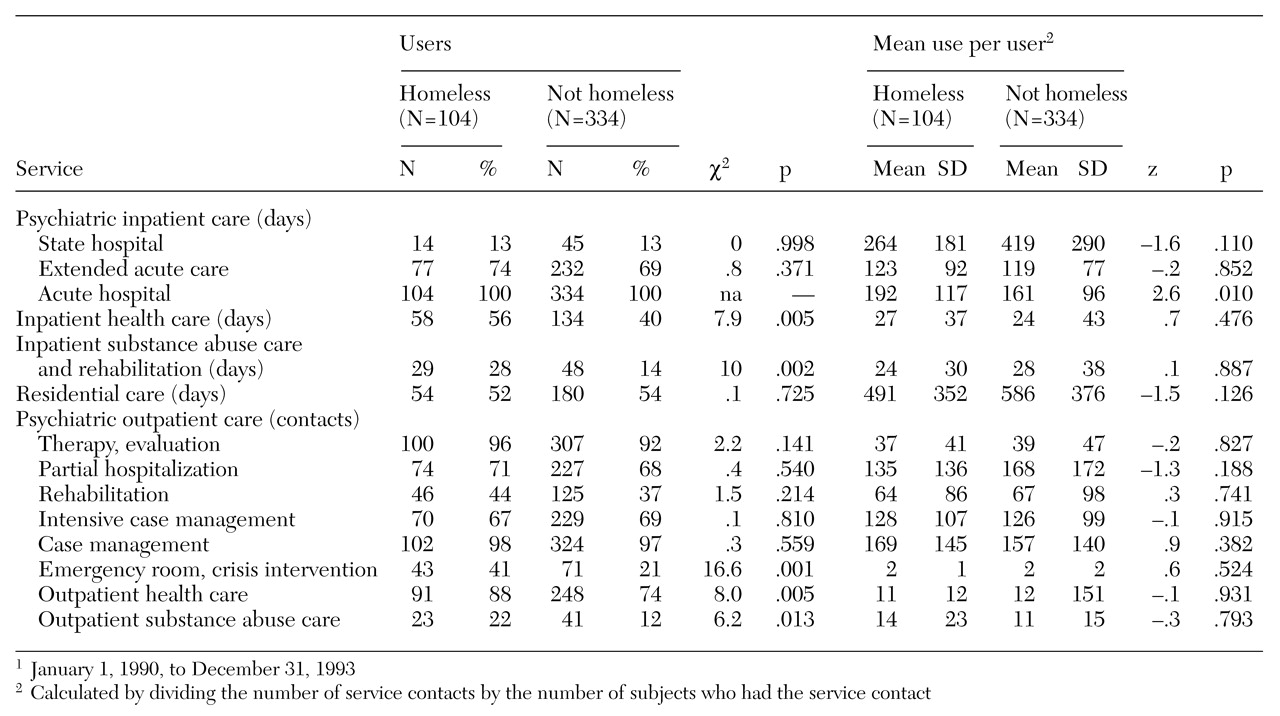

Table 2 presents data on the service utilization patterns of both groups during the four-year study period. The homeless subjects used significantly more psychiatric acute care hospital days (192 days versus 161 days). They were significantly more likely to use outpatient emergency-crisis intervention services (41 percent versus 21 percent). In addition, a greater proportion of homeless subjects received drug and alcohol treatment services in both inpatient settings and outpatient settings (inpatient, 28 percent versus 14 percent; outpatient, 22 percent versus 12 percent). Furthermore, a significantly larger percentage of homeless subjects were hospitalized for medical care (56 percent versus 40 percent), and a larger percentage visited a physician for a medical reason (88 percent versus 74 percent). The most frequently cited reason for hospitalization among the homeless subjects was "injury and poisoning." These seriously mentally ill individuals who experienced homelessness were more severely incapacitated than those who maintained stable housing.

The results from the multivariate logit model were consistent with the findings from the univariate analyses. The analysis showed that sociodemographic variables were stronger predictors of homelessness than the type and intensity of mental health treatment. The variables that increased the likelihood of homelessness were being African American (beta=1.07, odds ratio=2.91); having a substance abuse episode (beta=.654, OR=1.92), and receiving general assistance (beta=.57, OR=1.77).

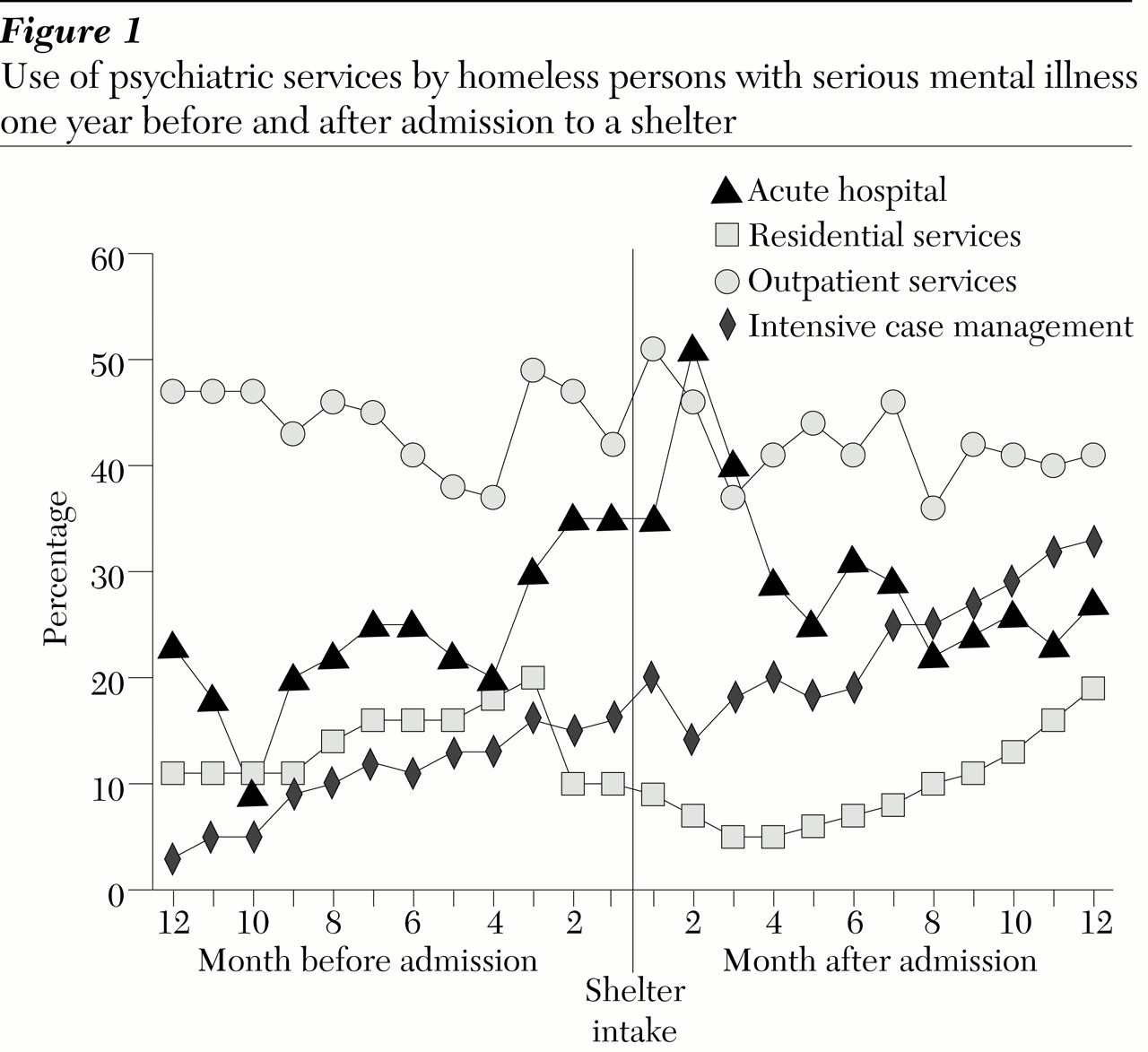

Service use before and after a shelter admission

Figure 1 shows the pattern of mental health service use for 91 homeless subjects in the year before and after admission to a shelter. Acute hospital admissions were highest in the month after a shelter admission (51 percent). In the months after the admission, as the percentage of subjects admitted to a hospital declined, the percentage admitted to extended acute care facilities and enrolled in community rehabilitation residences increased. Similarly, use of intensive case management services increased in a linear fashion as the length of time since shelter admission increased. Approximately one-third of the 91 subjects received intensive case management services after the shelter episode. Forty to 50 percent of them received some type of outpatient psychiatric services both before and after the shelter episode.

Discussion and conclusions

This study had several limitations. First, the study sample included only homeless individuals who were known to the mental health and shelter systems. Homeless individuals living on the streets or not in treatment were thus excluded. From a design perspective, the study did not have a comparison group from the period before the state hospital closed; the shelter registry did not exist before 1989. Also, no specific community treatment intervention was used. Nevertheless, this opportunistic sample permitted an investigation in a unique naturalistic setting where an enriched system of community resources was established using the money from closure of the state hospital. The findings raise questions about the relationship between services provision and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness.

Despite the large amount of resources that went into the enhancement of the ambulatory and residential mental health system, episodes of homelessness among a subgroup of acute patients persisted (24 percent), particularly among young African-American individuals who experienced extreme poverty and who had co-occurring drug or alcohol disorders.

In addition, contrary to the notion that homeless persons with serious mental illness are noncompliant with ambulatory psychiatric treatment, our findings suggest that these individuals had as many ambulatory service contacts as those who did not experience homelessness. Thus receipt of outpatient care did not seem to prevent homelessness among a subset of persons with serious mental illness. However, an increasing number of subjects began to receive intensive case management services after their homeless episode. Whether such services are enough to prevent recurrence of homelessness is a matter that deserves further study.

Although we cannot say that the state hospital closure resulted in an increased risk of homelessness among persons with serious mental illness, we can say that community outpatient mental health treatment was not sufficient to prevent homelessness in this high-risk population. Eleven percent of persons in our study experienced homelessness after referral to an extended acute care facility. Strategies to prevent homelessness should perhaps be considered at the time a patient is discharged from the referring community hospital or the extended acute care facility. For example, provision of practical and emotional support at the point of transition from institutional to community living has been found to significantly increase patients' chance of retaining housing (

3). Homelessness prevention efforts could result in more effective use of resources, given the higher level of use of medical and substance abuse treatment, psychiatric hospitalization, and emergency room services among homeless persons with serious mental illness.

This study examined homelessness in the seriously mentally ill population after closure of a state hospital. The findings serve as a baseline to measure progress of the community mental health system in dealing with the homelessness problem in this population.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Pew Charitable Trusts grant H92-01985-000.