Study design and sample

A cross-sectional survey was designed to replicate the 1987-1988 National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) (

9,

10,

11). NVVRS identified higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among African-American and Hispanic veterans than among white veterans. In 1990 Congress mandated an NVVRS-like investigation to collect prevalence data for other minority groups, including American Indians. The ensuing American Indian Vietnam Veterans Project (AIVVP), conducted between 1992 and 1995, followed procedures approved by institutional review and councils of participating tribes (Beals J, Holmes T, Ashcraft M, et al, unpublished manuscript, 2000).

AIVVP samples were recruited from two distinct tribal groups in the Southwest and in the Northern Plains. To protect community confidentiality these tribes are not named (

12), but they can be described generally. The Southwest sample was drawn from one of the largest reservations in the United States. Although about 150,000 people live on the reservation, population density is only six people per square mile, compared with the national average of 60. Unemployment is very high (

13).

The Northern Plains sample was drawn from three closely related reservation communities. These communities represent a combined geographic area of several thousand square miles and have a combined tribal enrollment of about 48,000. The area is rural and is economically disadvantaged. More than 50 percent of the population on each reservation meet poverty criteria.

Tribal rolls define the membership of a given tribe. Samples were drawn equally from these rolls from Northern Plains and Southwest groups. Veteran status was obtained from state and tribal records and verified in an interview. Only Vietnam veterans were eligible, and only those living on or within 50 miles of the reservation were selected. Samples were limited to men, since few women from these communities served in Vietnam. Only persons born between 1930 and 1958 were selected; this group encompassed over 95 percent of the men who served during the Vietnam era.

In the Southwest, this selection procedure produced a sampling frame from which potential respondents were chosen at random. In the Northern Plains reservations, it produced our study sample, which included all available veterans. A total of 316 Southwest and 305 Northern Plains veterans completed interviews. At each site, more than 90 percent of those selected were located, and more than 90 percent of those located agreed to participate. The overall response rate was 80 percent. Analyses are weighted to reflect sampling in the Southwest and to adjust for missing data in both tribal groups. Detailed weighting information is available for the authors.

Interviews were administered by trained lay staff using the same procedures for both tribal groups (

14). The instrument assessed personal characteristics, physical and mental health status, and service use.

Health measures and service use measures

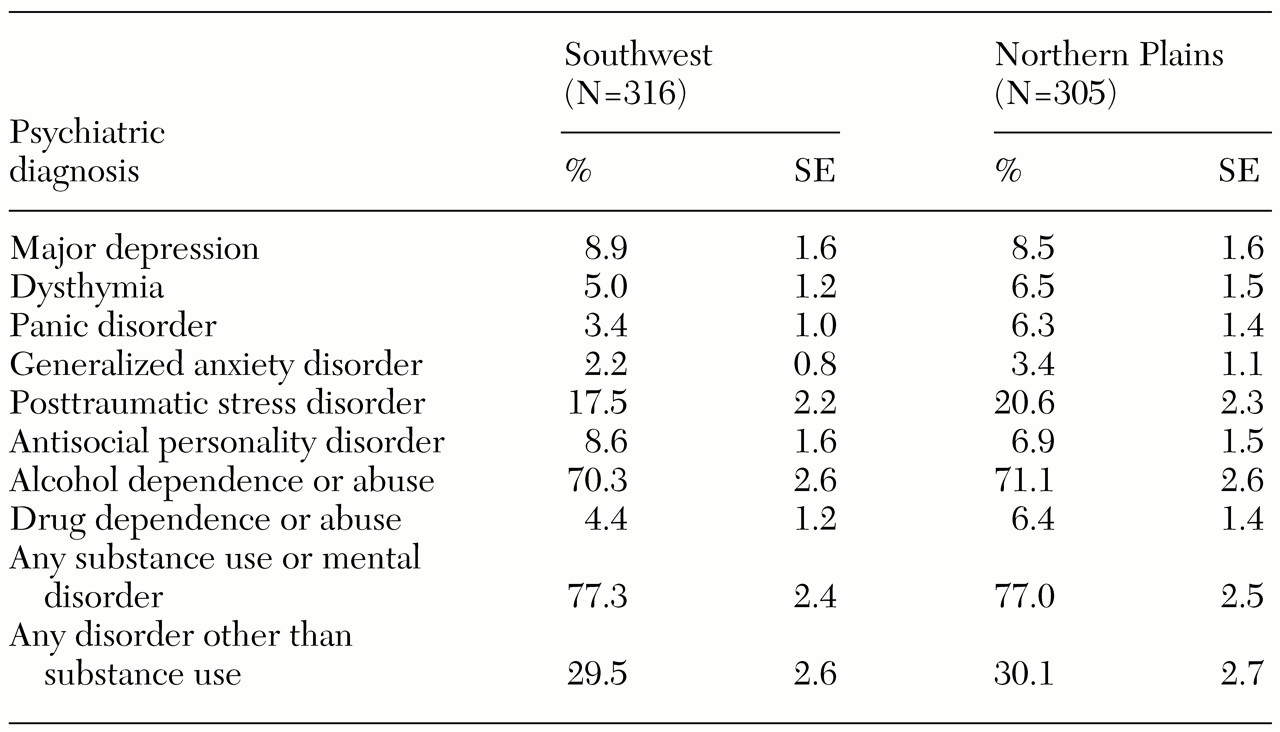

Health measures. Mental health status was based on

DSM-III-R (

15) criteria and included mental and substance use disorders. Substance use conditions were assessed using a form of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) adapted for use in the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) (

16). We reviewed the NCS-CIDI in focus groups of veterans, families, and providers from the Southwest and the Northern Plains, making modifications only when items were incomprehensible or culturally inappropriate. Our analyses considered

DSM-III-R diagnoses made within the 12 months preceding the interview.

To assess physical health, we asked veterans if they currently experienced any of 15 health conditions. The health conditions were selected because they are prevalent on these reservations and have important implications for service use.

Service use measures. The service ecology on reservations is complex and warrants description. Three main sources of care are available for biomedical care of mental and physical health problems: the Veterans Administration (VA), which offers outpatient and hospital care; the Indian Health Service (IHS), which also offers clinical and hospital care (

17); and other providers, including off-reservation private facilities and tribal substance abuse programs (

6). Mental health services provided by these facilities incorporate many approaches in addition to biomedical services; the term "biomedical" is meant here only to describe services offered in the context of hospital and outpatient care.

Availability, accessibility, and affordability vary among the services. VA care is limited to service-related disabilities and is priced according to disability. In the Southwest, the nearest VA outpatient clinic is 20 miles from the easternmost reservation border, but the nearest VA hospital and specialty services are located in urban areas 180 miles and 265 miles away, respectively. Trips to these facilities from the center of the reservation may take more than a day, and they are often complicated by bad weather and lack of transportation.

In the Northern Plains, reservations are smaller in land area and VA services are much closer. Still, the nearest VA facility is 90 miles from a reservation boundary, and reaching it requires a two-hour drive over poor secondary roads.

In contrast, IHS services are similarly available across the Northern Plains and the Southwest. The IHS maintains a hospital on each of the three Northern Plains reservations and several freestanding ambulatory clinics in outlying districts; the large reservation in the Southwest has four IHS hospitals, and another four are available in nearby towns at similar geographic distances (

13). IHS services are also available without cost to all tribally enrolled American Indians.

Private care is available only to off-reservation communities, and costs are generally prohibitive for groups with low incomes, high unemployment, and few insurance benefits. At the time of this study, tribal health programs were inconsequential.

American Indian communities have a rich history of traditional care through consultation with medicine men and ceremonies. Costs associated with traditional care can be high, running to thousands of dollars, and no insurance policies cover this care. Although reimbursements for ceremonies are now possible through VA under special circumstances, at the time of this study such coverage was not available. Family members often contribute to the cost of ceremonies, which are likely to involve family and community members. Time is also a consideration: some ceremonies require a week to perform, and consultations may take hours.

Use of biomedical services was measured separately for VA, IHS, and other biomedical providers, including state and private hospitals, treatment centers or clinics, and private physicians. For each provider group, participants were asked whether they had been hospitalized in the provider's facility within the past 12 months and whether they had gone to the provider for outpatient or clinical care for a physical health problem within the past six months. They were then asked whether they had received help from the provider for personal problems, problems with alcohol or drugs, or emotional problems from the war. The 12-month and six-month time frames were chosen to correspond to NVVRS questions about VA service use.

Traditional healing was assessed similarly. Respondents were asked whether they had gone to a medicine man or traditional healer or had a ceremony for a physical health problem within the past six months and whether they had used these sources within the past 12 months for help with personal problems, problems with alcohol or drugs, or problems from the war.

We present analyses of current health service use, which means any hospitalization at a VA, IHS, or other inpatient facility within the past year; any VA, IHS, or other outpatient facility used within the past six months; any traditional healing option used for physical health problems within the past six months; and any traditional option used for personal or alcohol problems or problems from the war within the past year.

Analysis

Analytic aims. We had three analytic aims. The first was to examine overall levels of service use, stratified by service sector and tribal group. The second was to describe comparative patterns of use among biomedical and traditional healing systems. The third was to explore variations in patterns of use across systems of care that are differentially available to the two tribal groups.

Hypotheses. By design, veterans in our study were demographically similar and were similarly eligible for services through VA and IHS. However, VA services were more readily available to Northern Plains veterans. Accordingly, we expected differences in patterns of service use. We tested four a priori hypotheses about biomedical care.

We first hypothesized that the use of biomedical services would vary as a function of need. This premise assumed that veterans of the two tribal groups would use biomedical services similarly, given similar needs. Because the availability of VA services is lower in the Southwest, we expected Southwest veterans to make greater use of IHS services to address health care needs.

Alternatively, we hypothesized that biomedical service use would vary as a function of availability. Because the availability of biomedical services differs between the sites, we hypothesized that total biomedical service use would be less in the Southwest, where VA services are less readily available. Under this premise, we expected IHS service use to be the same, given similar health care needs.

Traditional healing options are also available among the possible health care choices. We considered that when traditional options are included, use of particular providers might vary according to availability, and overall service use would operate as a function of health care needs. Hypotheses for combined traditional and biomedical care were also specified.

Our third hypothesis was that overall service use, including use of traditional healing, would vary according to need. We predicted that overall service use would be the same across tribes, given similar needs, when traditional healing options are included among the health care choices.

The fourth hypothesis was that use of all services, including traditional options, would vary as a function of availability. This hypothesis suggests that veterans in the Southwest would make greater use of traditional healing to offset lower biomedical service availability.

Statistical analysis. All analyses were conducted with SAS and SUDAAN, a companion statistical package developed by the Research Triangle Institute to weight for sampling and response bias (

18). Utilization rates were evaluated by univariate analysis. We report the percentages that responded affirmatively to service use questions, along with standard errors of the estimates. Service use patterns across systems of care were assessed by first combining all biomedical service use for physical problems, all biomedical service use for mental and substance use problems, and all traditional healing options used for these purposes, and then evaluating associations by cross-tabulation and chi square testing. Service use differences between groups were assessed by t test.