Measures

The EEOC database includes claimant demographic information, the statute (or statutes) under which the charge was filed, issues alleged in the charge, the claimant's self-reported disability (or disabilities), the EEOC office handling the charge, the dates associated with receiving and closing the charge, the charge's priority assignment, and the final charge outcome (

15).

Demographic variables in the database include the charging party's gender, race, ethnicity, and age. The EEOC database provides no information about income, so we included a variable specifying the average household income in the claimant's zip code. Because household incomes within zip codes are not homogeneous, we used this proxy as a reflection of economic opportunities or neighborhood effects that may influence the charging party. Because of skewness, the natural log of zip code area household income was used in the regression-based analysis.

To denote charges filed under multiple statutes, we incorporated separate dummy variables for charges filed simultaneously under the ADA and either the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) or Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Each of the 19 major issues under which charges can be filed were included as dummy variables. A variable denoting charges citing more than one issue was also included.

Cases involving persons with psychiatric disabilities were defined as cases in which the charging party reported at least one psychiatric disability as a basis for discrimination. The EEOC database has categories for four specific psychiatric impairments—anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and manic-depression—and a fifth category labeled other psychiatric illnesses. We created dummy variables for each of the five categories. In addition, because preliminary analysis showed HIV infection to be a categorization outlier compared with other nonpsychiatric disabilities, we included a dummy variable denoting a self-reported disability of HIV infection. Had we not included this variable, the model would not have been correctly specified. Because claimants may cite more than one statute and may report up to six disabilities and up to eight issues, dummy variables must be interpreted as nonexclusive. In the regression-based analyses, the disability reference category became complainants reporting neither psychiatric disability nor HIV infection.

In bivariate analyses, we included all three priority categories. In the multivariate analysis, we wanted to determine what factors predict whether a charge will be given the highest priority and thus receive a full investigation. Because category B was developed as a holding position until further information was gathered, we dichotomized the dependent variable, with charges classified as category A coded 1 and those classified as category B or C coded 0.

In the multivariate analysis, we used a time variable indicating the period when the charge was initially received as a control variable. We defined the first period as the initial implementation period of the ADA's employment provisions, from July 26, 1992, through June 30, 1995. This period preceded the implementation of the charge priority handling procedures, but it covers charges that were received during that time and then prioritized and closed later. Subsequent periods are divided into six-month blocks, until the final period, which is a three-month block running from January 1 through March 31, 1998. Periods were coded from 1 to 7, in chronological order. To account for the nonlinear relationship between time and assignment of priority category, we used the squared value of the time variable in the multivariate analysis.

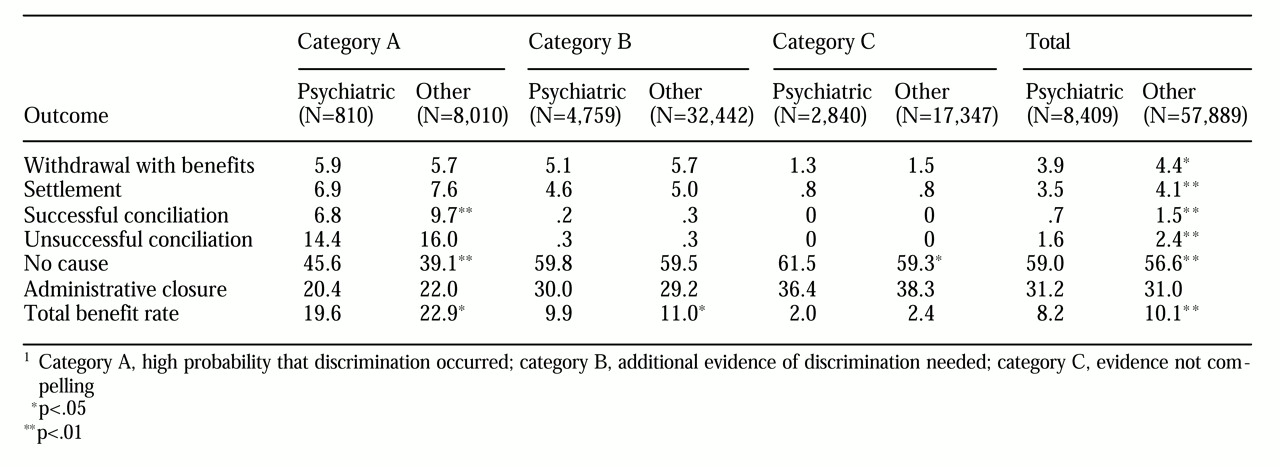

Three of the six major categories of charge resolutions benefit the charging parties. "Withdrawal with benefits" and settlements are agreements between charging parties and employers that resolve charges before the EEOC has finished its investigation and determined the merits of the charge. In this outcome, the charges are resolved by the parties independently without the formal involvement of the EEOC. Settlements, by contrast, involve the EEOC as a party. Conciliation agreements are settlements achieved after the EEOC has established reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred (

12).

Three other resolutions bring no direct benefits to charging parties. An outcome of "no cause" is an EEOC determination that there is not reasonable cause to believe that discrimination has occurred. An "unsuccessful conciliation" is a failure to obtain a settlement after an EEOC investigation established reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred. An "administrative closure" is a charge closed for other reasons without a cause determination (

12).

Table 1 presents summary statistics on the variables used in the model.