Over the past ten years, several studies conducted in the United States have indicated that a large proportion of patients with severe or persistent mental illness engage in behaviors that place them at high risk of contracting HIV—for example, promiscuity, intravenous drug use with shared needles, and unprotected sex (

1,

2). Although clinical factors such as poor reality perception, affective instability, and impulsiveness play a major role in such behaviors (

2), inaccurate information about HIV infection is also a significant variable. Lower levels of knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention have been found among chronically mentally ill patients (

3) and psychiatric inpatients and outpatients (

4,

5) than among nonpsychiatric patients. Misinformation was found to be associated with high rates of reporting of HIV risk behaviors (

6). However, patients with severe or persistent mental illness who engaged in such behaviors did not believe that they were being exposed to HIV infection (

7).

Despite the worldwide importance of the HIV epidemic and the data concerning the risk of HIV infection among patients with severe or persistent mental illness, only a few studies in Europe have examined this topic. The aim of this study was to examine the level of knowledge about HIV transmission and preventive measures among patients with different types of psychiatric disorders in Italy.

Methods

Participants were recruited at two local inpatient psychiatric units and two mental health outpatient clinics in Ferrara, in northeastern Italy, during one calendar year—1998. The eligibility criteria were that participants be 18 to 55 years old, without a primary diagnosis of substance abuse, and, in the case of the most severely ill, clinically capable of participating in the research as evaluated by a psychiatrist—for example, not exhibiting severe psychotic disorganization. Psychiatric diagnoses were made according to the ICD-10. For the control group, persons with ages and educational levels similar to those of the psychiatric patients were recruited in the waiting rooms of the hospital medical clinics when they came for regular checkups or treatment of physical illness. A brief psychiatric interview was conducted to exclude individuals with past or current psychiatric disorders.

For each participant, after the aims of the study were explained and informed consent was obtained, the Italian version of the AIDS Risk Behavior Knowledge Test (AIDS-KT) (

4), translated and back-translated for accuracy, was given. The AIDS-KT is an 11-item true-false self-report instrument devised to assess the accuracy of knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention among psychiatric patients. Possible scores on the AIDS-KT range from 1 to 11, with higher scores indicating better knowledge. Statistical analysis was performed, including descriptive statistics, the chi square test, the t test, and regression analysis, when appropriate. The significance level was set at .01 or less to control for multiple statistical comparisons.

Results

Of 243 eligible patients who were approached, 214, or 88 percent, agreed to participate. Of these, 105, or 49 percent, were men and 109, or 51 percent, were women. The mean±SD age of the patients was 36.27±9.43 years; 114 patients, or 53 percent, were inpatients, and 100, or 47 percent, were outpatients. The ICD-10 diagnoses of the patients were schizophrenia (99 patients, or 46 percent); affective syndromes—for example, major depression, dysthymia, or bipolar disorders (43 patients, or 20 percent); personality disorders (38 patients, or 18 percent); and neurotic syndromes—for example, anxiety, somatoform, or adjustment disorders (34 patients, or 16 percent). The time since diagnosis ranged from one year to 25 years, with a mean±SD of 5.9± 5.6 years and a median of six years. Most patients (N=141) had had at least one previous psychiatric admission; the mean±SD was 5.5±12.1 admissions, the range was zero to 82 admissions, and the median was four admissions.

Of the 115 persons eligible for the control group who were contacted, 88 individuals, or 76 percent, agreed to participate. Of these, 43 participants, or 49 percent, were men and 45, or 51 percent, were women. The mean age of the control subjects was 35.34± 9.23 years. They were more likely than the psychiatric patients to be married (χ2=6.49, df=1, p=.011).

The AIDS-KT showed an acceptable level of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.72). The mean± SD score for the psychiatric patients was lower than that for the control subjects (8.2±1.8 versus 9.6±.7; t=6.9, df=300, p<.001). Psychiatric inpatients' scores were also lower than those of the control group (7.8±1.7; t=9.33, df=200, p<.001), as were psychiatric outpatients' scores (8.5±1.8; t=5.38, df=186, p<.001). Among the psychiatric patients, inpatients had lower scores than outpatients (t=2.8, df=212, p=.005). The proportion of participants who had a score of 9 to 11—representing good knowledge—on the AIDS-KT was 51 percent for the psychiatric patients and 91 percent for the control subjects (χ2=39.6, df=1, p<.001).

Among the psychiatric patients, the median number of correct answers was nine, or 81 percent correct, compared with ten, or 91 percent correct, among control subjects (χ2=3.3, df=1, p<.06). Two variables were significantly associated with higher levels of misinformation—the duration of mental illness (beta=.27) and the number of psychiatric admissions (beta=.19) (R2=.10, F=8.4, p<.001). The total AIDS-KT score was not related to age or education for either group.

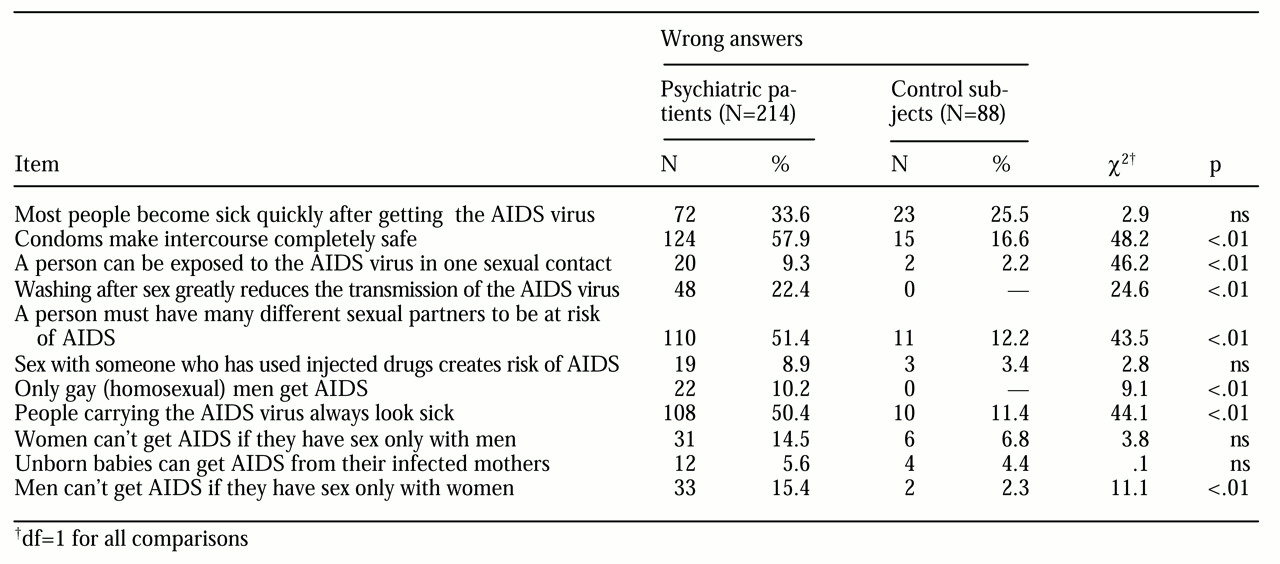

The distribution of responses to the single items of the AIDS-KT is shown in

Table 1. Psychiatric patients gave more wrong answers than did control subjects for most of the items, although for some items this difference was modest. The most significant differences were found among patients with schizophrenia and personality disorders, whereas the responses of patients with affective or neurotic syndromes differed only marginally from those of the control subjects. Among psychiatric patients, 60 of 166, or 36 percent, reported having been tested for HIV in the past; of these, three, or 5 percent, were reportedly seropositive. No corresponding information was available for the control subjects.

Discussion

This study indicated that understanding of HIV transmission and prevention was generally lower among patients with mental illness than among nonpsychiatric patients in this Italian sample. Misconceptions were more evident among inpatients, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, patients with repeated psychiatric admissions, and patients with long-lasting illness than among patients with less severe disorders, such as neurotic syndromes.

These results confirm that there is a need for patients with severe or persistent mental illness to receive education about HIV infection. In fact, it has been shown that misinformation about HIV transmission tends to be associated with HIV risk behavior (

3,

4,

5). However, educational and cognitive-behavioral programs that are specifically developed for patients with mental illness tend to focus on reducing the level of risk behavior (

8). It seems that only a minority of mental health services routinely assess knowledge of HIV transmission and risk behavior among patients with severe or persistent mental illness (

9).

Certain caveats are in order in examining the results of this study. First, although the AIDS-KT has been used in other studies (

4), it is possible that some ambiguous items may have influenced our participants' responses. Ambiguity might have stemmed from the different epidemiology of HIV infection across countries—HIV infection is more prevalent among intravenous drug users in Europe, especially in Italy, than among homosexual men, whereas in the United States infection is more prevalent in the latter group. However, recent reports of HIV risk behavior such as substance abuse, unprotected sex, promiscuity, and homosexual activity among persons with severe or persistent mental illness in Italy are consistent with the results of U.S. studies (

10).

Second, apart from information about HIV, clinical variables such as impulsiveness, poor judgment, and positive symptoms, which were not examined in this study, have been strongly implicated in high-risk behavior among patients with severe or persistent mental illness (

1,

2,

5). Thus educational programs should not be limited to interventions that simply increase knowledge about HIV infection but should extend the focus to clinical factors, including patients' motivation and readiness to change their behavior.

Despite the limitations of our study, Italian mental health services should give more attention to the problem of HIV risk among patients with severe or persistent mental illness by implementing HIV educational campaigns.