In recent years, the prescription of psychotropic medications to youths under the age of 18 years has become more common (

1,

2,

3). However, with the exception of data on stimulants for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), relatively few studies have been published on the sociodemographic characteristics of youths for whom psychotropic medications are prescribed or on the clinical management approaches used in the prescription of psychotropic medications for youths in the community (

1,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8). Such studies of pediatric pharmacoepidemiology can help identify determinants of access to treatment with psychotropic medications. These data can then be used to assess the extent to which community treatment is consistent with recommended guidelines for the prescription of psychotropic medications to youths, an issue that has received little direct attention (

1,

6,

9).

Jensen and colleagues (

1) described the overall prescription rates of psychotropic medications to patients under 18 years of age in the United States by using data from the 1995 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Disease and Therapeutic Index. Stimulants were the most commonly prescribed, although prescription of other psychotropic medications was not infrequent. The use of anxiolytics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and stimulants has increased in recent years (

1,

5,

8). Jensen and colleagues commented on the paucity of data supporting the efficacy or safety of most of these agents among youths. However, neither their study nor any other has provided data on the sociodemographic characteristics of youths to whom these medications are prescribed.

Another area that has remained largely unexamined is the clinical management approaches to prescribing psychotropic medications to youths. Using data from the 1985 NAMCS, Kelleher and colleagues (

10) described the clinical management provided with prescriptions of psychotropic medications, and with stimulants specifically, during visits by youths to office-based practices. Only a small minority of visits during which a psychotropic drug was prescribed also involved psychotherapy and the scheduling of a follow-up appointment. Close monitoring of clinical changes and side effects associated with psychotropic medications prescribed to youths is particularly important, because many of the clinical indications are "off-label," and fewer data are available to guide the course of treatment (

1). However, with the exception of Kelleher's work (

10), no recent studies have systematically addressed this issue.

In this study we used NAMCS data to examine patterns of prescription of psychotropic medications to children and adolescents in office-based medical practices. We collected demographic and diagnostic data and information on the source of payment associated with the use of each major class of psychotropic medication—antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and stimulants—during these visits. We also examined the medical specialties of the physicians who prescribed each class of medication. Finally, we updated and expanded existing information on clinical management approaches associated with the prescription of specific classes of psychotropic drugs.

Methods

The NAMCS is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which samples a nationally representative group of patient visits to physicians in office-based practice as defined by the American Medical Association and the American Osteopathic Association (

11).

We obtained information about a total of 166,256 visits to a national sample of office-based physicians who participated in the NAMCS from 1992 to 1996. On the basis of recommendations of the NCHS, we combined data from the surveys during that four-year period to establish a larger base from which to derive estimates (

11). A total of 17,347 physicians were sampled. Of these, 5,912 were deemed ineligible for the study, or out of the study's scope, mainly because they had retired; had died; were employed in teaching, research, or administration; or had not seen any patients during the study period because they were on vacation or were ill. Among the 11,435 eligible physicians, the overall response rate for the four-year study period was about 72 percent.

Survey design

The NCHS uses a multistage probability sampling design for the NAMCS. Counties or standard metropolitan statistical areas are stratified by size, region, and demographic characteristics (

11). The surveys were conducted in three stages. First, a probability sample of 112 primary geographic sampling units was drawn, followed by a probability sample of practicing physicians, stratified by specialty within these primary sampling units. Finally, a systematic random sample of the visits to these physicians was drawn. Attending physicians or their office staff completed a one-page data form for each visit, which defined the sampling unit. The form contains items such as basic demographic characteristics; payment sources; diagnoses; medications prescribed, supplied, or administered; and medications that patients continued to take with or without a new prescription.

Only minor modifications were made to the survey between 1992 and 1996; a more detailed description of the survey's design and procedures has been published elsewhere (

12). The sampling period was one week. Physicians who expected more than ten visits a day recorded visits on the basis of a predetermined sampling interval, which may have resulted in some patients being recorded more than once. Data were obtained from general practitioners, pediatricians, psychiatrists, child psychiatrists, and all other physicians who reported visits from patients aged 19 years or under.

Because selection was not completely random, a weighting and downweighting procedure was used to convert the data from the sample into data that could be treated as coming from a simple random sample. Such weighting corrects for the design effect of a stratified complex sample. Because the NCHS's exact sampling probabilities have not been published, multivariate analyses of these data cannot take advantage of adjustment for nonrandom sampling. We used the downweighting method of Lee and colleagues (

13), which is a conservative strategy for approximating a simple random sample.

Measures

During each visit, patient record forms were used to collect information on prescriptions and several sociodemographic and clinical characteristics—for example, age, sex, and ICD-9 diagnosis. The three items used to describe the clinical management that was provided with prescriptions of psychotropic medications were psychiatric diagnosis, psychotherapy, and disposition of the visit. Three spaces are provided for recording ICD-9 diagnoses on the patient record form. Disposition of the visit was grouped into two categories, "scheduled follow-up" and "no follow-up planned." An item on the form specifically coded whether or not psychotherapy or counseling was provided.

Prescription of a psychotropic medication refers to whether a drug was prescribed, refilled, or recommended or whether a drug sample was given to a patient. Psychotropic medications were grouped to determine prescription patterns. Antidepressants included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics, venlafaxine, trazodone, and nefazodone. Anxiolytics included alprazolam, clonazepam, and other benzodiazepines. Antipsychotics included haloperidol and fluphenazine. Valproic acid, lithium, and carbamazepine were grouped under mood stabilizers. The stimulant category included methylphenidate, pemoline, and amphetamine compounds.

Information on payment source for each visit was recorded on the physician record form. Categories of payment source included health maintenance organization, Medicaid, Blue Cross-Blue Shield, other private insurance, and payment by the patient.

Analytic strategy

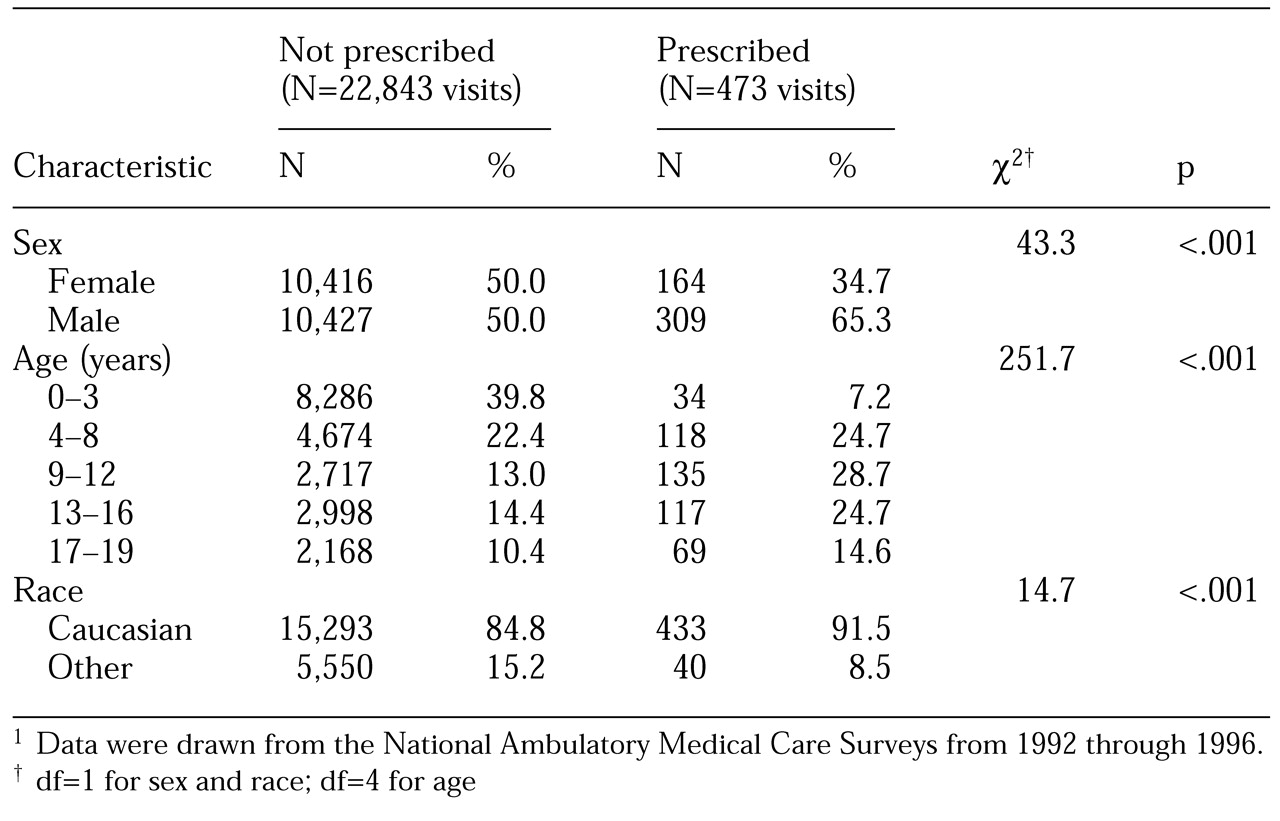

In the first series of analyses, we used Pearson's chi square test to compare the sociodemographic characteristics of patients aged 19 years and under who did and did not receive a prescription for a psychotropic medication during an office-based ambulatory care visit. Next, the demographic characteristics of patients who received a prescription for each class of medication were compared with the characteristics of those who received a prescription for any other psychotropic medication. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was set at .05 or less.

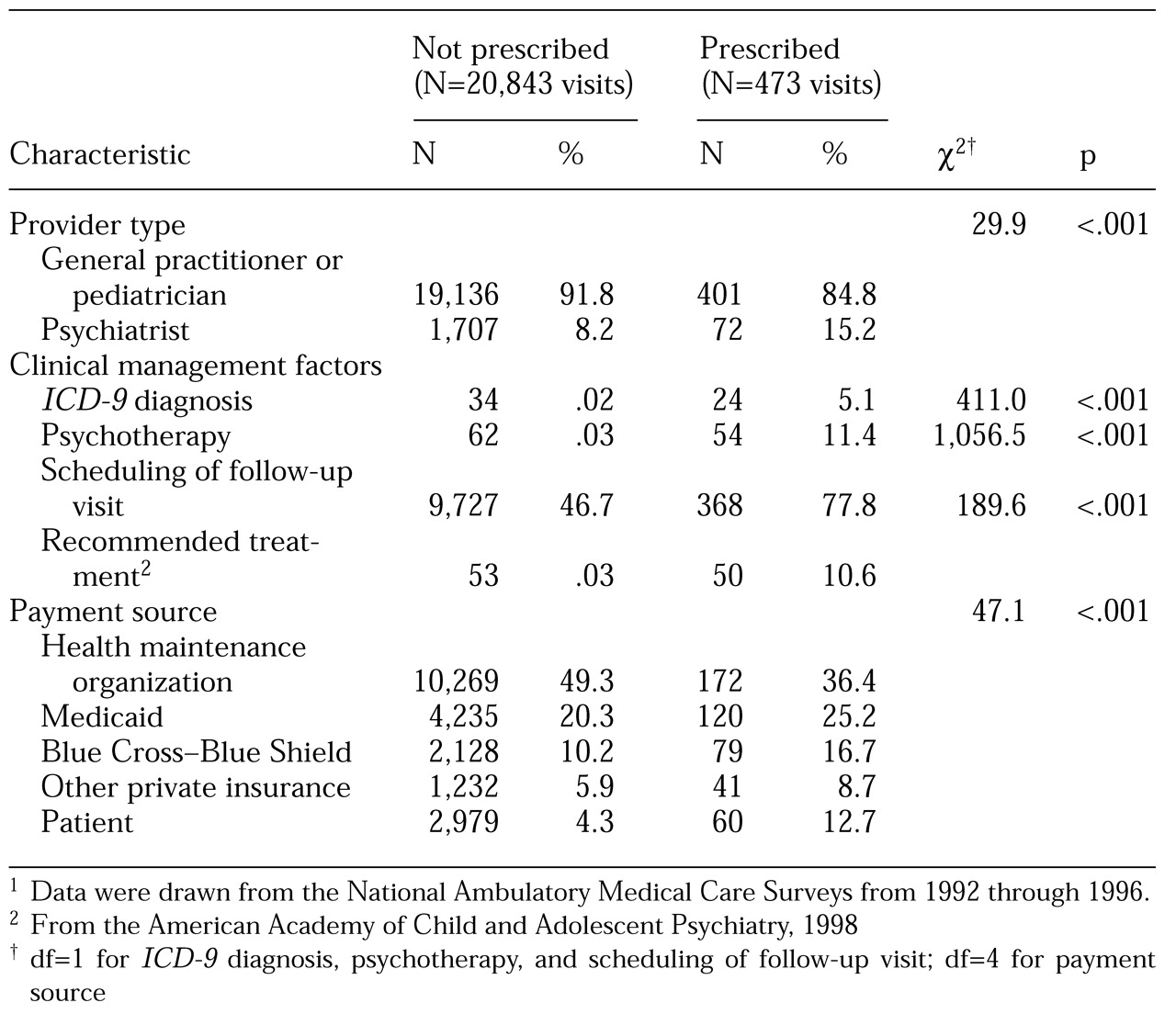

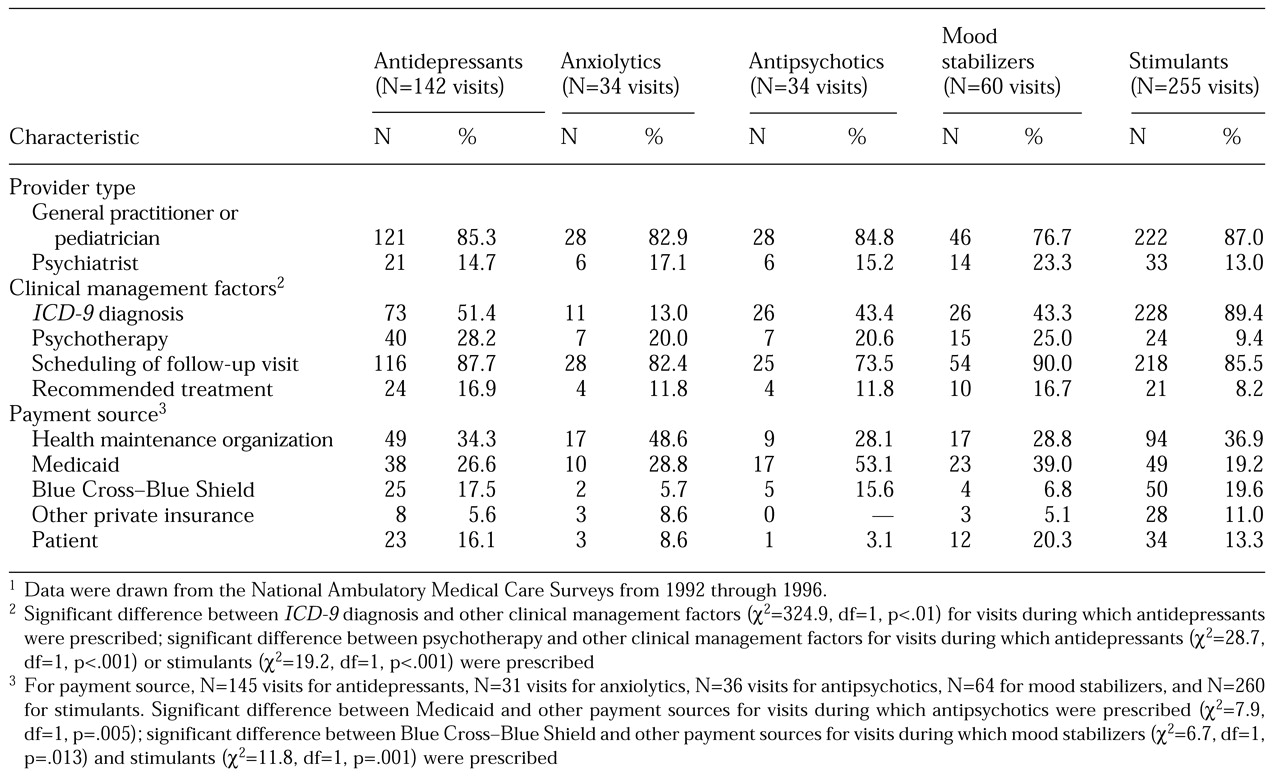

In the next series of analyses, we used Pearson's chi square test to compare differences in physician specialty (general practitioner, pediatrician, or psychiatrist), the number of visits that involved documentation of a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 290 to 319), whether psychotherapy was provided, whether a follow-up appointment was scheduled, and the source of payment for visits that did and did not involve a prescription for any psychotropic medication. The same method was then used to compare visits that involved a prescription for each class of medication with visits that involved a prescription for any other psychotropic medication.

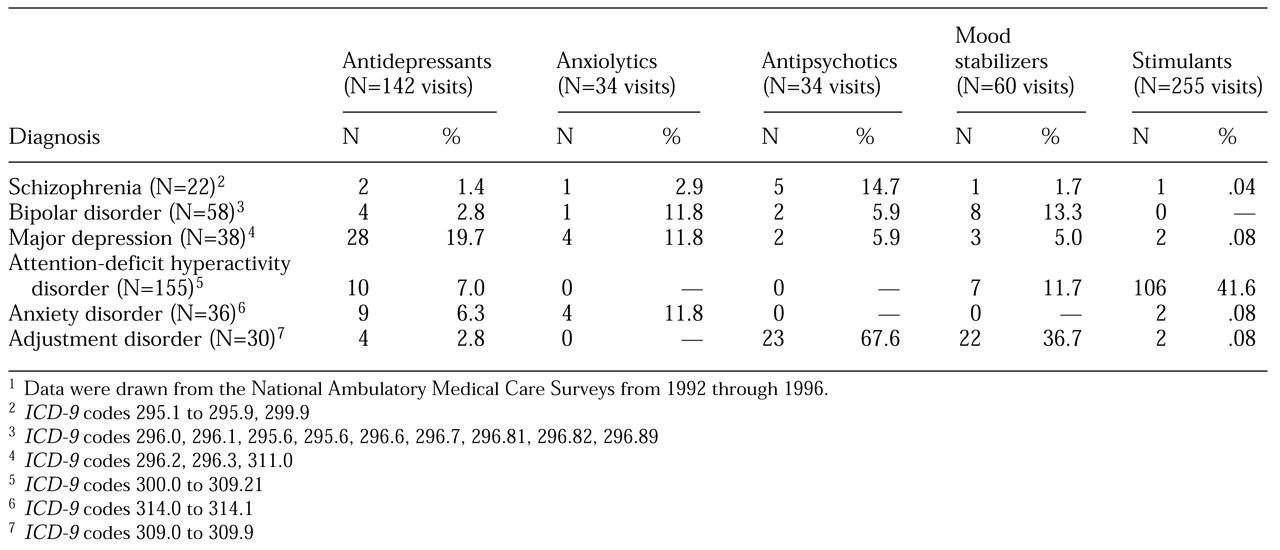

Finally, we computed the numbers and percentages of specific ICD-9 diagnoses associated with prescriptions for each class of medication. Diagnoses of anxiety disorder were collapsed into one category, because of the small number of patients with panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Because of the small subsamples, formal tests of association were not conducted.

Discussion

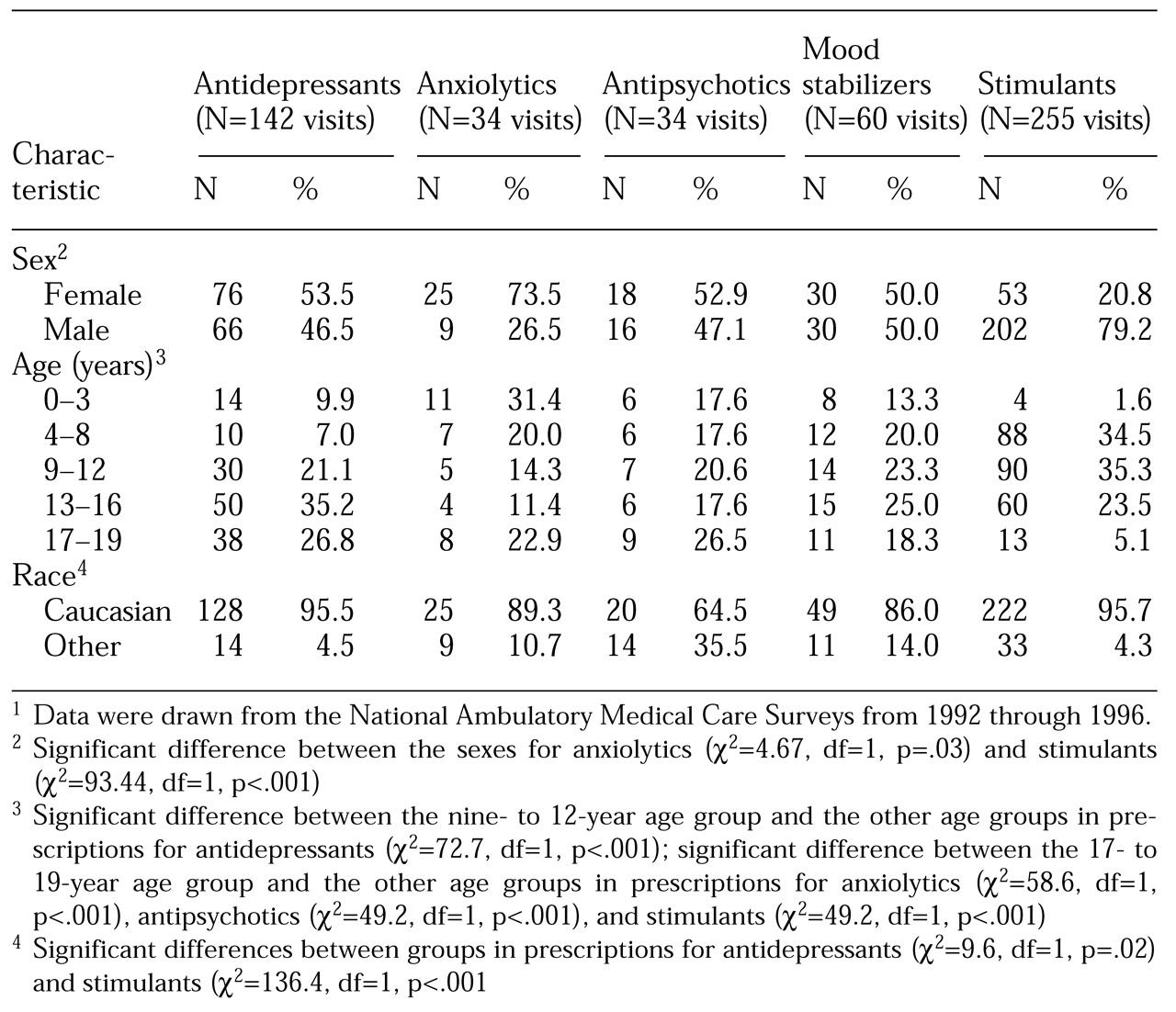

In this study we documented the sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses, and clinical management approaches associated with prescription of each major class of psychotropic medication to youths who visited office-based medical practices in the United States. Use of these medications is common among children and adolescents.

The visits during which each class of medication was prescribed had several notable attributes in common as well as some distinct characteristics. The age and sex differences we observed for prescribing patterns appear to be in accord with epidemiologic and clinical data on the differences in prevalence of mental disorders between sexes and between different age groups; for example, prescription of stimulants is more common during visits by male youths (

14,

15). However, no data exist to suggest that the prevalence of mental disorders is higher among Caucasian children and adolescents than among children of other races. The reasons for the observed racial disparity in prescribing patterns remain unknown. The data are consistent with and expand on previous findings of racial inequalities in the prescription of stimulants to children and adolescents (

15,

16,

17,

18).

For example, Zito and colleagues (

15) found that African-American children were two and a half times less likely to receive prescriptions for stimulants than their Caucasian counterparts. In addition, Melfi and colleagues (

18) found in a Medicaid population that African-American children were less likely than Caucasian children to have received antidepressants when they were first diagnosed as having depression; when they did receive medication, the African-American children were more likely to have received prescriptions for tricyclics, whereas the Caucasian children were more likely to have received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Two possible explanations for the racial disparity in prescribing patterns are cultural differences in the expression of symptoms that result in lower rates of detection and treatment (

19) and cultural bias in diagnosis (

20). Alternatively, lower rates of use of mental health services among minorities, as found in several community-based studies, may help to explain the difference we observed, but it was not possible for us to control for service use. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown similar racial disparities in the treatment of ADHD, even after service use was controlled for (

21).

Our findings indicate that Medicaid is a major source of payment for visits during which psychotropic medications are prescribed for children. Interestingly, our observation that antipsychotics and mood stabilizers—but not antidepressants—were more likely to be paid for by Medicaid are consistent with the findings of other studies (

15,

18). None of these findings definitively address the question of why psychotropic drugs were more likely to be prescribed for children during visits paid for by Medicaid.

However, it is certain that these findings highlight the increasingly apparent need for research that addresses the quality of care and equity in the quality of care for Medicaid recipients. Given that Medicaid is the largest source of health insurance for children and adolescents in the United States (

22), research on the quality of care and issues that affect quality is extremely important for this population. The fact that youths who are covered by Medicaid are more likely to be of lower socioeconomic status—a strong risk factor for mental illness—highlights the potential impact on the health of this population of improving the quality of care (

23). The rate of prescriptions was also low among patients who belonged to health maintenance organizations, which might have been a result of an emphasis on primary care rather than on treatment by specialists, who are more likely to prescribe medications.

It is unclear why more than 30 percent of visits involving a prescription for a psychotropic medication did not also involve a psychiatric diagnosis. However, this finding is consistent with those of previous studies (

24). It has been suggested that physicians who are not psychiatrists—who provide a majority of psychotropic prescriptions—may improperly use psychiatric terms or may feel less comfortable with these terms, and thus they may be less likely to record psychiatric diagnoses. This phenomenon has been documented for the treatment of adult patients (

25). Other authors have hypothesized that some physicians intentionally misdiagnose—or neglect to document—psychiatric illnesses because of the stigma associated with these disorders (

26). Also, it is conceivable that vague behavioral problems for which there is no clear diagnosis are being treated pharmacologically.

In addition, the reluctance of physicians to diagnose mental disorders among pediatric patients may stem from a belief that neither a psychiatric diagnosis nor any available treatment will significantly alter the clinical course of the disease (

27). The infrequency with which psychiatric diagnoses were documented in our study is striking, yet it is not evident from these data alone that diagnostic practices affect quality of care, because the diagnoses recorded were generally consistent with the type of medication prescribed; for example, major depression was the most common diagnosis among visits during which antidepressants were prescribed.

This study had several limitations. First, because the NAMCS records visits rather than individual patients, the extent to which data for individual patients were duplicated is unknown. Second, although our findings can be considered to be representative of office-based practice in the United States, the response rate was only 72 percent, so response bias may have affected the results. Thus the generalizability of the results may be limited. Also, the NAMCS data do not provide information about prescribing patterns for psychotropic medications in hospitals, clinics, or university-based health care settings, nor on the frequency with which individual patients receive mental health services from two or more health care professionals.