The past decade has seen significant changes in the way inpatient mental health services are provided. With the advent of managed care, the development of new medications, and more intensive outpatient treatment programs, there is constant pressure to discharge patients from the hospital sooner. Inpatient care is the most expensive component of mental health services, so inpatient episodes are now typically brief and focused on managing crises and stabilizing symptoms. As a result, length of stay on psychiatric inpatient units around the country has progressively decreased. The American Hospital Association reports that the average stay in psychiatric hospitals declined from 75 days to 56 days between 1988 and 1992. Moreover, in the period from 1988 to 1994, length of stay for psychiatric patients in general hospitals declined from 12.1 to 9.6 days (

1).

The large proportion of patients who are discharged after very short stays raises questions about quality of care and the possible impact of early discharge on readmission rates. Studies of the relationship between length of stay and readmission rates have had mixed results (

2,

3,

4,

5). One study looked at the relationship between length of stay and readmission rate for all patients admitted to a university-affiliated adult psychiatric inpatient unit between 1985 and 1992 and found that in a population of privately insured patients, drastically shortening hospital stays did not result in an overall increase in recidivism (

2).

Similarly, another study found that reducing the average length of stay in an acute psychiatric unit from 25 days in 1988 to 16 days in 1994 did not increase the readmission rate (

5). In contrast, other authors who looked at recidivism among patients with schizophrenia have expressed concern that short hospital stays may not provide adequate preparation for discharge and may be associated with higher readmission rates, because discharged patients are now sicker (

3,

4,

6).

Results

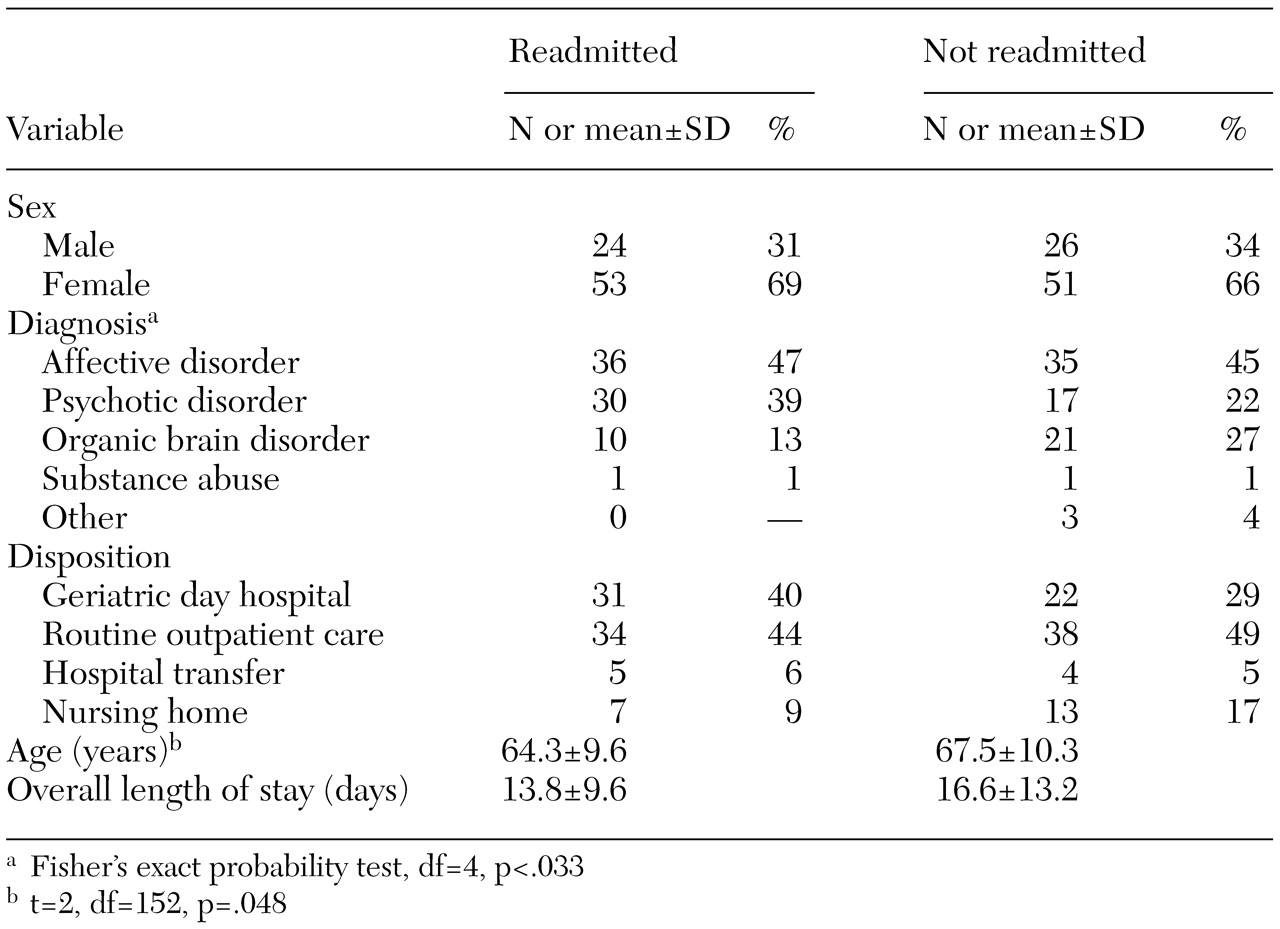

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 77 readmitted patients and the 77 randomly selected patients who were not readmitted are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age of the readmitted patients was 64.3 years, significantly less than the 67.5 years for patients who were not readmitted. The two samples also differed significantly in type of diagnosis. The largest group of readmitted patients met criteria for a mood disorder, which included major depression, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, and other forms of depression. The next largest group of readmitted patients were diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder, which included schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and other psychoses, and an organic brain disorder—either delirium or dementia secondary to various causes. By comparison, the patients who were not readmitted had more than double the rate of organic brain disorders and about 50 percent fewer psychotic disorders. For the five-year period, the mean length of stay for readmitted patients was about three days less than that for those who were not readmitted; however, this difference was not statistically significant.

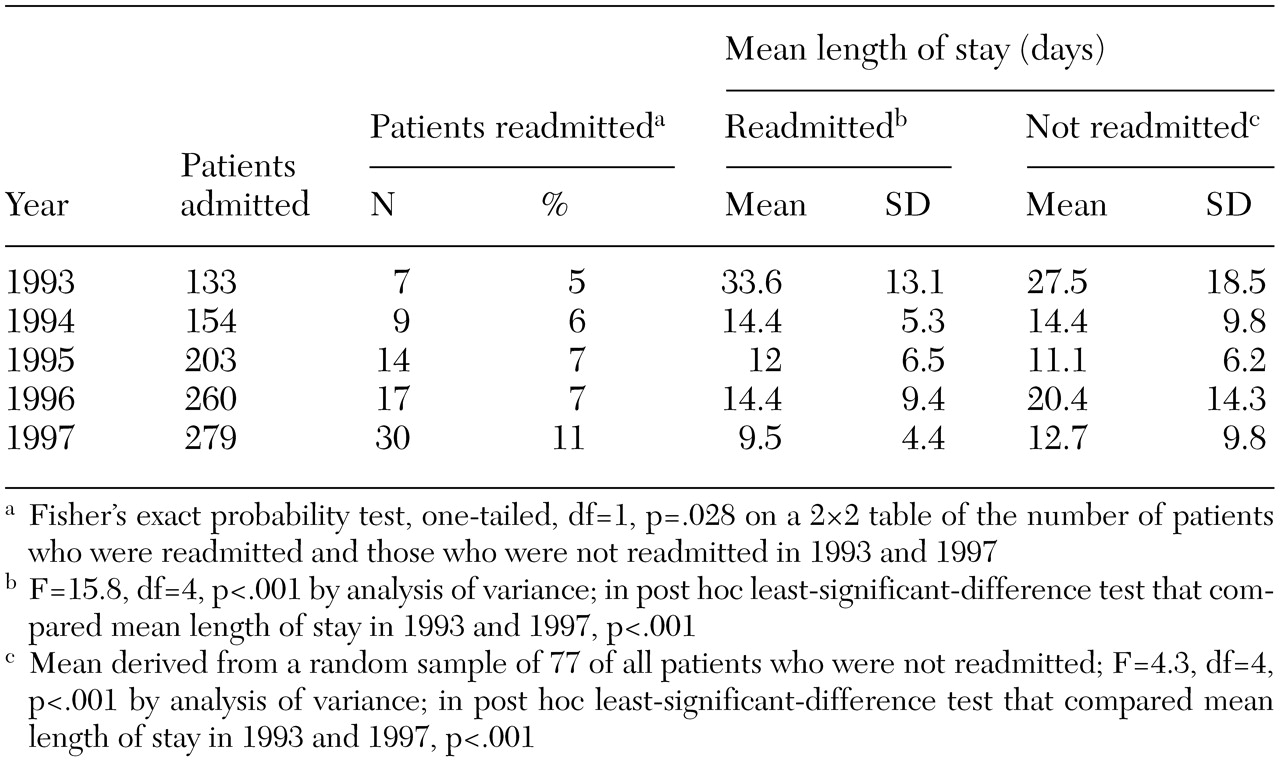

Analyzed by year, data on length of stay and readmission revealed some interesting trends, as can be seen in

Table 2. For readmitted patients, the mean length of stay for the index admission decreased significantly over the five years, from 33.6 days to 9.5 days, a decline of 72 percent. The mean length of stay for patients who were not readmitted also decreased significantly, from 27.5 days to 12.7 days, but the decline was less severe —54 percent. During the same period, the overall proportion of readmitted patients doubled, from 5 percent (seven patients) in 1993 to 11 percent (30 patients) in 1997. There was also a dramatic increase in the proportion of patients who were discharged to the geriatric day hospital over that period, from 10 percent to 47 percent (two-tailed Fisher's exact probability test, p=.003).

Discussion

Our findings show a temporal association between decreasing length of stay and rate of readmission to our university hospital psychogeriatric unit between 1993 and 1997. As the overall mean length of stay for all patients declined from 29.6 to 15.2 days, the readmission rate doubled, from 5 percent to 11 percent. This temporal association suggests—but does not prove—that the readmission rate doubled because length of stay declined. Over the same five years, the proportion of patients who were discharged to the geriatric day hospital more than quadrupled, which suggests a need for more intensive outpatient treatment. It is possible that readmission rates would have been higher if not for this more intensive outpatient treatment. It is also possible that the existence of the day hospital raised the inpatient treatment team's expectations that patients could tolerate shorter stays.

The trend toward shorter stays between 1993 and 1997 was probably in part a product of economic and administrative forces. Medicare began reimbursing day hospital programs in 1991 (

11), making it possible to provide more intensive outpatient treatment to older patients. Meanwhile, greater internal and external review of the medical necessity of inpatient care meant that patients were discharged sooner and therefore needed the more intensive outpatient care of a day hospital to prevent relapse and readmission. Our findings indicate that discharging more patients to the geriatric day hospital did not prevent the readmission rate from increasing. As a group, the patients who were readmitted were actually more likely than those who were not readmitted to be discharged to the day hospital (40 percent compared with 29 percent), although this difference was not statistically significant.

Beyond the main focus of our research, which was to answer the question about the relationship between decreasing length of stay and readmission rate, our findings provide some insight into the characteristics of readmitted psychogeriatric inpatients. Although it can be argued that a three-day difference in length of stay is clinically significant for an individual patient, our finding of no statistically significant difference in the overall mean length of stay between patients who were readmitted and those who were not during the study period suggests that length of stay is not the only factor that determines whether a patient is readmitted.

Thus our findings are consistent with the explanation that other factors, including diagnosis, severity of illness, and disposition, in combination with length of stay determine whether a given patient is readmitted. The patients who were readmitted were significantly younger and, accordingly, had lower rates of organic brain disorders, such as dementia and delirium, and were less likely to be discharged to a nursing home. These findings suggest that elderly persons who have organic brain disorders and are therefore often incapable of independent living are less likely to be readmitted because they are discharged to supervised settings, such as nursing homes and assisted living facilities, where medication monitoring, behavioral interventions, and in-house psychiatric consultation are readily available to prevent relapse.

It is also possible that older patients had a higher rate of death within 30 days of discharge and therefore were not readmitted. Given that we do not have follow-up information on patients who were not readmitted, we cannot determine the extent to which mortality played a role in the rate of readmission of the older patients.

This study had several important limitations. First, we do not know whether any of the patients were readmitted to one of the other inpatient psychiatric units in the area within 30 days of discharge from our unit. Thus it is possible that we significantly underestimated the readmission rate and that some of the patients whom we included in the comparison group were actually readmitted to other hospitals. We considered that obtaining this information would be prohibitively laborious and time-consuming.

Second, the study sample was relatively small, which limited the power of our statistical analyses. For example, the difference of almost three days in overall mean length of stay for patients who were and those who were not readmitted would have reached statistical significance with a sample of 268 readmitted patients (alpha=.05, beta=.2, power=.8). Third, ours is a mostly middle- and lower-income, inner-city geriatric population. We must be careful when extrapolating these results to psychogeriatric inpatient units that serve different—and possibly more resourceful—populations.

Fourth, the age cutoff for the inpatient unit is 50 years, which is younger than that for most other psychogeriatric units. Fifth, the data were retrospective, and the scope of the study was confined to the type of data available from the patients' discharge forms. For example, we could not determine the relationship between readmission rate and severity of illness, because we did not have a measure of severity. Thus this study can serve as a pilot study for a more extensive, prospective study that would include ratings of severity of illness at admission and discharge as well as follow-up of patients after discharge to determine whether they were admitted to other area hospitals.