In the context of psychiatry, insight is defined as the ability to recognize that one has a mental illness or is experiencing psychopathological symptoms (

1). Although insight is a relevant focus of intervention for people with a range of mental illnesses, most research in the area has focused on its relevance to schizophrenia (

2). Higher levels of insight have been shown to correspond to better psychosocial functioning and clinical outcomes (

3).

Although a great deal of research has addressed lack of insight, little information is available to guide clinicians in working with clients who have impaired insight. Studies that link insight to severity of symptoms offer hope that treating the symptoms will improve insight (

4). However, more information is needed to develop psychosocial interventions in this area.

It has been suggested that identity, quality of life, and a sense of control are instrumental in shaping the explanatory models that people develop to understand the experience of mental illness (

5). If these factors are relevant to insight, they could be targeted for psychosocial intervention. In this study we aimed to clarify the relationship between severity of symptoms, engulfment, locus of control, quality of life, and insight among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Methods

Respondents were recruited through notices posted at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto. Potential participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were asked to contact a research assistant, who explained the study and obtained informed consent. Medical charts were reviewed to confirm illness history and DSM-III-R diagnosis. Exclusion criteria included known organic brain disorder or mental retardation. The study, which was conducted during 1995 and 1996, was approved by our institutional review board.

Five instruments were used to assess the patients. Insight was assessed with the Schedule for Assessing Insight (

1), a structured interview that evaluates three dimensions: awareness of illness, capacity to relabel psychotic experiences as abnormal, and treatment compliance. The respondent answers questions from an interview schedule, and responses are coded with use of anchors on a scale from 0 to 2, with higher scores indicating a higher level of insight. The summation of seven questions produces a maximum score of 14 and a minimum score of 0.

Quality of life was assessed with the Quality of Life Interview-Short Version (

6), a structured interview for psychiatrically disabled persons that assesses objective and subjective quality of life in eight dimensions: living situation, daily activities, family relations, social relations, finances, work or school, safety, and health.

Engulfment was assessed with the Modified Engulfment Scale (

7), which assesses the development of deviant or sick roles—with the exclusion of other roles—in response to the experience of mental illness.

The Internality, Powerful Others, and Chance Scales (

8) measure belief in chance as opposed to expectancy as having a role in control exerted by "powerful" others or perceived mastery of one's personal life.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (

9) rates symptoms over the previous week on the basis of 18 items that are assessed through a semistructured interview.

The data were subjected to preliminary analyses to assess suitability for regression analysis. Regression analyses were used to assess the contribution of engulfment, internality, and subjective quality of life to insight. Diagnosis and severity of symptoms were also included, because they have been identified in previous research as important variables.

Results

The sample contained 25 people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 33 people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder; 31 were men and 27 were women, with similar representation of the sexes between the two diagnostic groups. The mean±SD age of the participants was 41.1±8.4 years. The mean duration of illness was 18.4±9.5 years, and the mean number of previous hospitalizations was 7.8±9.1. Most of the participants were single or never married (39 participants, or 67 percent) and unemployed (39 participants, or 67 percent).

No significant differences were found between the diagnostic groups in illness variables or sociodemographic variables, with the exception of education, severity of symptoms, and subjective quality of life. Patients with bipolar disorder were more likely to have had a college or university education (Mann-Whitney U=228.00, p<.05). In addition, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were assessed as having a greater severity of symptoms (t=−2.096, df=56, p<.05) and a lower subjective quality of life (t=2.295, df=56, p<.05). The mean± SD score on the Schedule for Assessing Insight was 10.4±3.6, and t tests indicated no significant difference in scores between the two diagnostic groups (9.8±4 and 10.8±3.2 in the schizophrenia and bipolar groups, respectively). Analysis of covariance indicated that the levels of insight in the two diagnostic groups remained equivalent when the variance associated with severity of symptoms and with subjective quality of life was removed.

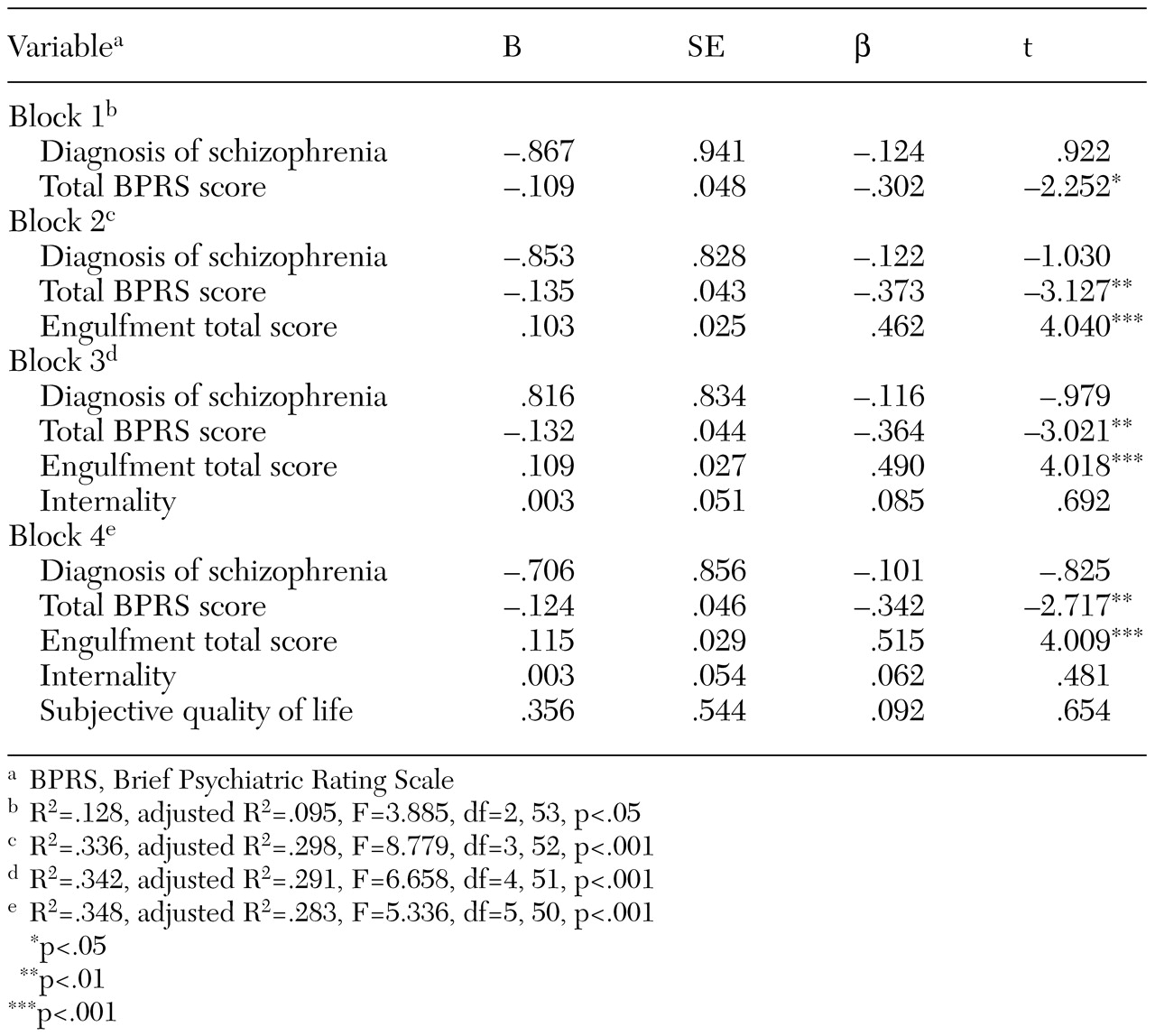

The hierarchical regression model included diagnosis, severity of symptoms, engulfment, internality, and subjective quality of life as possible predictors of insight. The results of the analysis are summarized in

Table 1. The first block, which contained diagnosis and severity of symptoms, was significant but accounted for little of the variance (adjusted R

2=.095). For the second block, with engulfment added, the adjusted R

2 was .298. For the third block, with internality added, the adjusted R

2 was .291. For the final block, with subjective quality of life added, the adjusted R

2 was .283. Standardized beta coefficients indicated that engulfment scores and severity of symptoms were the only independent predictors in the regression equations.

Discussion and conclusions

The participants in this study had relatively high levels of insight into their illnesses. As was found in other studies (

4,

10), patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar disorder did not differ significantly in their insight.

The association between severity of symptoms and insight has been found in other studies and reinforces the notion that the promotion of recovery is central to all interventions in this patient population (

3). However, engulfment in the patient role has not received much attention in the literature. Engulfment is particularly relevant to psychosocial care, because psychological and social interventions address identity issues. The results of this study suggest that the desirable outcome—insight—is associated with an undesirable outcome—engulfment.

The Modified Engulfment Scale characterizes the patient role as identifying oneself as a patient and acknowledging a need for medical help. However, this role is also associated with ideas of being damaged and deviant (

7). Thus it is apparent that insight and engulfment are overlapping constructs that have some important differences. The significant association between insight and engulfment suggests that psychosocial interventions that focus on promoting insight must not only address the internalized stigma that threatens self-esteem but also promote the development of an identity that can incorporate health-seeking behaviors without destructive role constriction.

Internality and subjective quality of life were not associated with insight in this study, which may suggest that insight into illness is more closely tied to illness-specific factors. Given that we used a small convenience sample, our results are preliminary and should be interpreted and applied with caution. Nevertheless, results suggesting that severity of symptoms and engulfment are the most significant predictors of insight in this sample of outpatients with serious mental illness reinforce the importance of integrating sensitivity to these issues into strategies for supporting insight among similar patients.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant from the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry Research Fund.