Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living (

1), a flexible and highly individualized form of social skills training, has been continuously offered for more than 30 years in community mental health centers, outpatient clinics, private practices, state hospitals, and veterans' medical centers throughout the world (

2). Because this type of training uses basic principles of human learning that apply to everyone—such as goal setting, modeling, behavioral rehearsal or role playing, repeated practice, positive reinforcement for small changes, and community-based assignments—persons with every type of disorder who come for psychiatric services can be involved (

3).

Building on the motto of the National Association of Social Workers, "helping people help themselves," social skills training aims more specifically to teach people to help themselves. Skills training enables clients to learn how to get their own needs met with less involvement of case managers and other clinicians.

Procedures used in the module

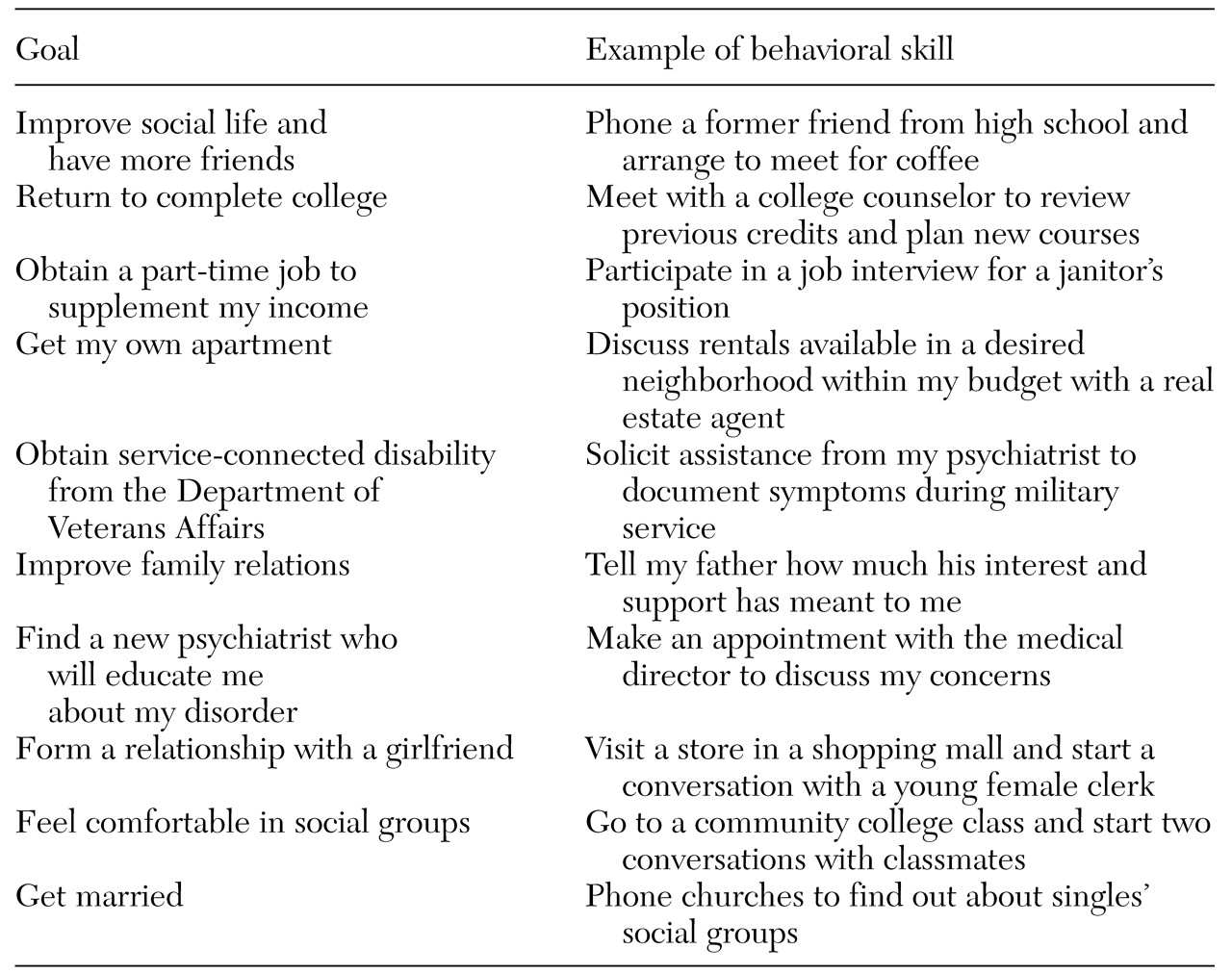

The Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living module, which can be conducted in individual, family, or group formats, begins with the clinician's assisting clients to articulate their personal long-term goals. This is the most technically challenging part of the training, because many individuals will get stuck focusing on their symptoms or problems and pose their goals in negative terms, such as "I'd like to be free of my depression," "I'd like to be able to leave the hospital," "I don't have enough money to enjoy life," or "I don't want to be so lonely." The clinician must help the client translate these problems into positive goals by asking questions such as, "What would you like to be able to do/like to do/enjoy doing if you were free of your depression or voices?"; "What can you do to convince your doctor that you are ready to leave the hospital?"; "How might you reduce your expenses or earn some money?"; and "Do you know anyone with whom you could meet and do things together?" Some personal goals of consecutive clients who have participated in this type of skills training, framed in positive and constructive terms, are listed in

Table 1. When skills training is conducted in a group, the members' personal goals are listed on a flip chart or marker board to maintain focus and overcome attentional deficits.

The next step is to help the individual identify a specific interpersonal action that, if accomplished, would bring that individual closer to his or her personal goal. Thus a series of stepwise, incremental goals leading to the personal goal of "having more friends" might begin with "attend a Bible class where there would be others who share my interest in religion," "sign up for tennis instruction at the local recreation district," "join the Sierra Club and go on its weekly hikes with other members," "call a friend from high school with whom I've stayed in contact and invite him to join me for coffee or a movie," "ask my case manager whether she knows of anyone on her caseload whom I might enjoy getting to know," or "ask one of the members of my psychosocial club if I could join her for dinner at her table." Examples of concrete and short-term goals selected as targets for training in skills groups, linked to clients' various long-term personal goals, are also listed in

Table 1.

The acronym SMART (specific, meaningful, attainable, realistic, and transfer) can be used to recall the attributes of setting highly specific and incremental goals for the skills training. First, goals for training are specific: they are described by answering the questions "What is the goal?"; "With whom do I need to interact to achieve the goal?"; and "When and where will this interaction likely take place?" Second, the goals are meaningfully linked to a longer-term personal goal. Third, each goal should be attainable—neither too difficult nor too easy to accomplish in real life. Fourth, the goal should be realistic so as to be consistent with the individual's rights and responsibilities and to improve the individual's social functioning, while building on the individual's strengths, deficits, and resources. Finally, community-based case managers and natural supporters should be mobilized to promote the transfer of the skills practiced in the group into the clients' everyday life.

The procedures used for this type of flexible and individualized skills training have been described in treatment manuals (

1,

3,

4). The procedure usually takes no more than five or ten minutes per person, which makes group training with up to ten clients cost-effective. The principles used in training are based on procedural, active, and implicit learning that can compensate for many of the cognitive deficits experienced by people with schizophrenia and other mental disabilities. Thus benefits from skills training sidestep the neurocognitive obstacles posed by verbal learning, insight, and memory that characterize traditional "talk" therapies and discussion groups.

Once the specific goal for the skills training session is chosen and endorsed by client and clinician, a modeling interaction is provided by the clinician or, in the case of group sessions, by a peer who has the appropriate skills and experience. The modeling sequence is closely annotated, and the individual is asked to repeat the verbal and nonverbal elements of communication that were demonstrated by the model; for example, the eye contact, intonation of voice, facial expression, posture, gestures, phrases, and speech used to initiate and respond in the interaction. If the person is unable to identify the discrete skills that have been demonstrated by the model, this sequence may have to be repeated or made less complex.

Next, the individual has an opportunity to practice the verbal and nonverbal elements of the skill that were demonstrated by the model. However, the clinician stays close to the person while he or she goes through the role play and provides coaching and feedback to increase the adequacy of the performance. Immediate positive feedback is given to the person for whatever was done well. In a group setting, the leader structures and elicits positive feedback by asking each of the group members what he or she liked about how the leader communicated in each scene. Posters on the walls or on easels remind participants of the specific verbal and nonverbal communication and problem-solving skills that are the subjects for the training. Video feedback is often given, with special care taken to highlight the segments of the role play that showed positive communication skill. If it appears that the individual would benefit from further practice, additional rehearsing, either within the skills training session or outside of it, can be prescribed.

The "rubber hits the road" with homework or community assignments. Each person in training is given a reminder card with the date, assignment, and prompts to make good eye contact, speak with an appropriate tone of voice, use facial expression to convey emotions, and communicate with the goal in mind. Sessions should be at least weekly, but progress in achieving community-based, personal goals can be accelerated through the use of more frequent sessions.

Conclusions

Few outcomes are more valued by consumers than achieving their own personalized goals. This is the primary aim of social skills training. What better way to empower a mentally disabled person than to equip that person with the know-how and skills to meet his or her own needs without direct assistance from a clinician? Skills training operationalizes the ancient Chinese aphorism, "Give a man a fish and he has a meal; teach a man to fish and he can feed himself for life." The title "Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living" was chosen for the training module because it conveyed empowerment to clients and motivated them to participate in the gradual, effortful learning enterprise.

The further evolution, development, and dissemination of skills training methods will come from clinical services research and a broader focus on goals that are identified by consumers themselves. Controlled studies of skills training combined with supported employment are under way to determine whether teaching fundamental workplace skills can improve employment tenure among persons with serious and persistent mental illness. Because so many persons with mental disabilities are sexually active and at risk of unwanted pregnancy, rape, and sexually transmitted disease, a new Friendship and Intimacy module has been produced (

7). Computer-aided and errorless training are technical innovations aimed at enhancing individual-paced and efficient learning of skills.

Afterword: For many evidence-based psychosocial treatments that require programmatic overhaul and new human resources, organizational and administrative obstacles and lack of commitment from top and middle management may torpedo the effort. On the other hand, social skills training can be readily implemented by a single clinician even when others in the organization are not interested in this modality. We have noted the successful application of skills training when a psychologist decided to lead groups in an acute inpatient unit, an occupational therapist began a group in a partial hospital program, and a nurse developed a group for geropsychiatry outpatients.

The importance of acquiring social skills is underscored by a substantial body of research that has shown high correlations between social skills and community and social functioning, even after symptoms and cognitive impairment have been controlled for (

8). The growing use of social skills training in the mental health marketplace should reduce the burden and stress on case managers in intensive case management programs and should enable clients to steer their daily lives more autonomously (

9). The zeitgeist for this type of learning-based empowerment is favorable, as reflected by a new self-advocacy curriculum developed by the National Mental Health Consumers' Self-Help Clearinghouse, the National Mental Health Association, and the National Association of Protection and Advocacy Systems.