Psychiatric practice in nursing homes

A recent survey of practitioners suggested that psychiatric services in nursing homes, if they are available, are most commonly provided by a psychiatric consultant who works alone, comes only when called to see a specific patient, and does not provide subsequent care unless specifically called back (

8). This survey of clinicians, as well as a multistate survey of nursing home administrators (

6), concluded that traditional, "as-needed" consultation models are inadequate to address the many needs of nursing home residents and staff. Available data on nursing home practices by mental health clinicians are largely limited to the results of surveys of general psychiatrists (

9) and psychiatrists who specialize in geriatric psychiatry (

10).

An annual practice survey of a randomly selected sample of general psychiatrists in the United States conducted from 1982 to 1996 has shown a gradual increase in the proportion of American psychiatrists who have a substantial geriatric practice (

9). The proportion of psychiatrists for whom elderly patients constitute at least 20 percent of their caseload increased from 7.3 percent in 1982 to 14.5 percent in 1988 and then to 18.1 percent in 1996. This group of psychiatrists devoted 7 percent of their professional time to practice in nursing homes. Moreover, 14.9 percent had board certification with additional qualifications in geriatric psychiatry. In contrast, psychiatrists for whom elderly patients made up less than 20 percent of their caseload were unlikely to devote much time to nursing home practice, spending on average of only .5 percent of their time in nursing homes. These data suggest that despite trends showing an increase in the proportion of psychiatrists who treat older people, the vast majority of psychiatric practice in nursing homes is provided by a minority of clinicians who devote at least a fifth of their practice to geriatrics.

Not surprisingly, most psychiatrists who have a subspecialty in geriatrics routinely provided mental health services in nursing homes. Data from surveys conducted in 1997 by the Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry (

10) and in 1998 by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (

8) have shown that more than three-quarters of geriatric psychiatrists saw patients in nursing homes. The Canadian survey revealed that 78 percent of respondents worked in nursing homes and that they provided services for an average of 5.8 institutions (

10). Canadian geriatric psychiatrists reported that they spent, on average, 7.5 hours a week in nursing homes, which accounted for about a fifth of their professional time. Sixty-five percent reported that they worked within an interdisciplinary team structure.

The 1998 survey conducted by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry found that geriatric psychiatrists in the United States visited six nursing homes on average (

8), nearly the same proportion as their Canadian counterparts. At these facilities, they covered an average of 678 beds. At the primary nursing home where they worked, they spent an average of four hours per visit and saw nine residents for an average of 26 minutes per resident. Sixty-seven percent worked within a team consisting primarily of nurses (76 percent), social workers (62 percent), or psychologists (36 percent). This finding is comparable to the 65 percent of Canadian geriatric psychiatrists who reported working as part of a team. The most common treatment recommendations by geriatric psychiatrists in the U.S. survey included psychiatric medications (84 percent), changes in the general medical regimen (55 percent), staff support interventions (46 percent), medical diagnostic testing (37 percent), behavioral interventions (35 percent), staff training (30 percent), individual or group psychotherapy (20 percent), and family psychotherapy (13 percent). These data suggest that geriatric psychiatrists tend not to rely solely on pharmacotherapy, instead recommending a more diverse range of treatment interventions, as suggested by the treatment literature (

11,

12). This approach contrasted with the more typical pattern of exclusive reliance on pharmacotherapy that nursing home staff perceive to be inadequate (

6).

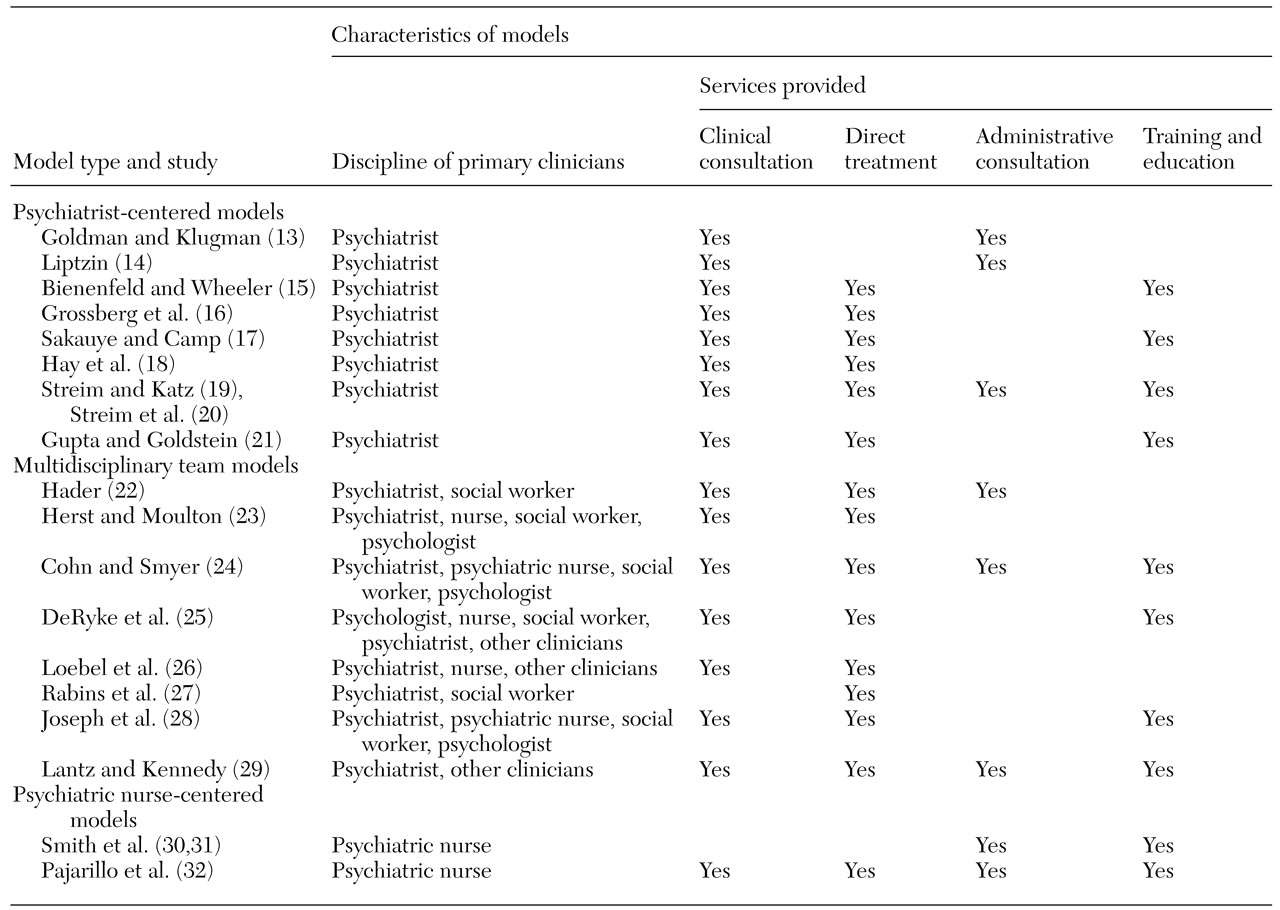

Models of mental health services

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of three models of mental health services in nursing homes—psychiatrist-centered models, multidisciplinary team models, and nurse-centered models. Psychiatrist-centered models emphasize the role of the psychiatrist as the primary and often the sole provider of direct consultation and clinical services (

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21). In this respect, the psychiatrist-centered model is an adaptation of the traditional hospital-based consultation-liaison model. In general, the psychiatrist responded to a request to provide clinical evaluation and treatment recommendations for a specific resident. Only a minority of the reports on this type of model included a description of administrative or program consultation provided to the nursing home managers, and only half explicitly described staff training and education.

In contrast, multidisciplinary team models included a variety of mental health clinicians with different roles and responsibilities (

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29). Teams varied in size from two individuals—for example, a psychiatrist and a social worker or another clinician—to as many as five clinicians, including a psychiatrist, a psychiatric nurse, a social worker, a psychologist, and other types of service providers. Most reports on these models described direct clinical consultation services to individual nursing home residents, and half described training and educational activities. Multidisciplinary team models emphasized the complementary contributions of different disciplines (

24). For example, the psychiatric nurse specialist may be more effective in directly relating to the nursing staff and in developing treatment plans, and the psychiatrist may be most influential in relating to the medical director and physician staff and providing recommendations for differential diagnosis and pharmacological interventions. Psychologists may offer specific expertise in behavioral programming and neuropsychological assessment, whereas social workers may have superior skills in addressing family and social support concerns.

Finally, two reports described nurse-centered models of mental health service delivery that are distinguished by the presence of a geropsychiatric nurse specialist who coordinates the service of other extrinsic mental health clinicians while providing training to develop the skills and abilities of the intrinsic nursing staff. These nurse-centered models (

30,

31,

32) emphasize routine administrative consultation to nursing home personnel and training of intrinsic direct care staff to provide mental health interventions within the nursing home. These models included a "train-the-trainer" approach in which an extrinsic geropsychiatric nurse specialist provides ongoing training and consultation to a nursing home staff nurse who becomes the internal "expert" responsible for training others.

Common themes among these models include an emphasis on the limitations of traditional consultation services provided on an as-needed or emergency basis. The reports emphasized the value of a team approach for providing ongoing routine services within the nursing home, ideally in the context of a formal contract for clinical, administrative, and training services.

Effectiveness of mental health services

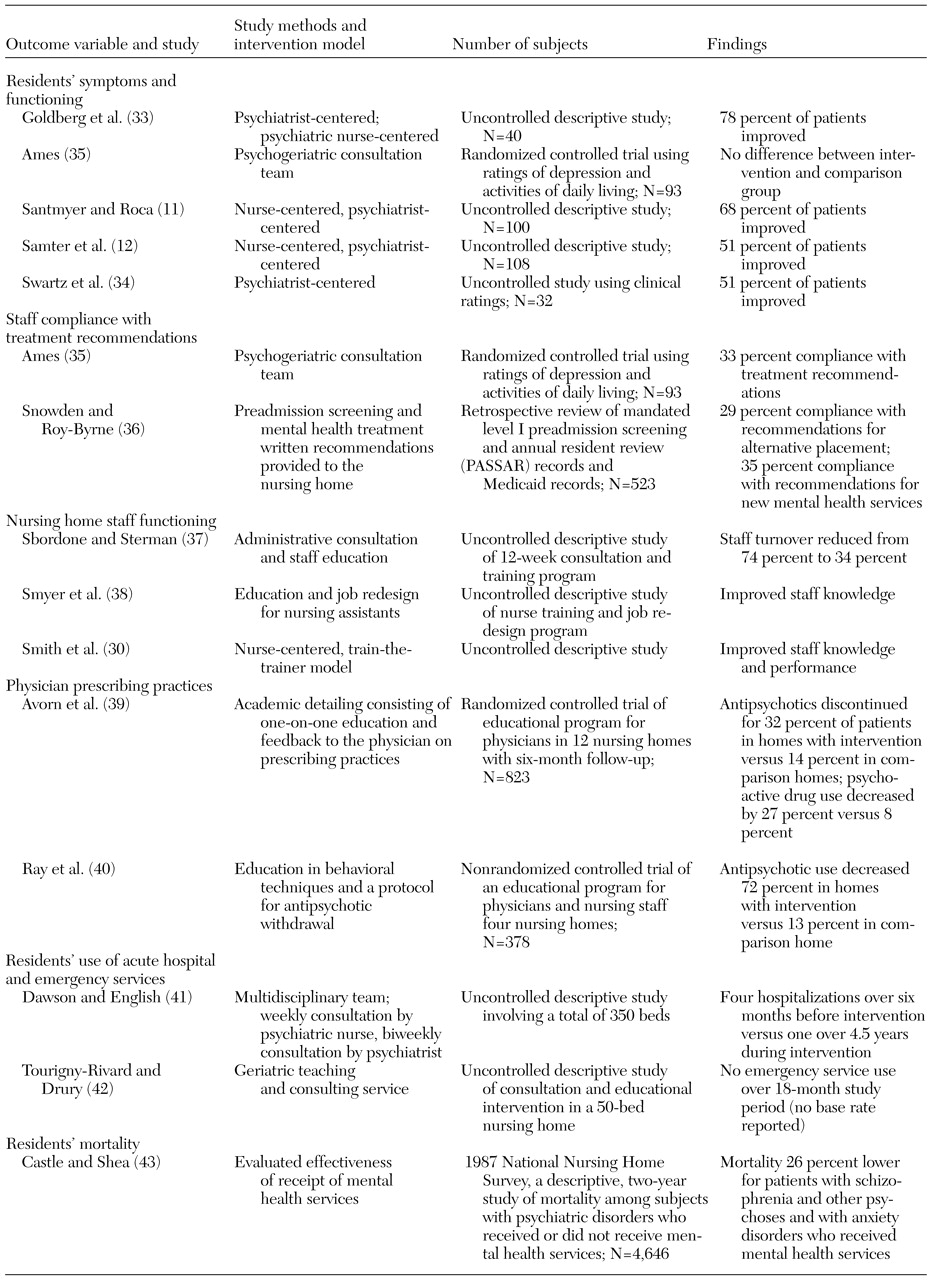

Few studies of the outcomes of mental health services in nursing homes have been conducted, and most have substantial methodological limitations. For example, a majority were observational studies that did not include a comparison group, and, in most studies, outcomes were rated by clinicians.

The findings of data-based studies are summarized in

Table 2, with emphasis on four overall categories of outcomes: residents' symptoms and functioning, residents' use of acute services, functioning of the nursing home staff, and physicians' prescribing practices. The outcomes of mental health services on residents' symptoms and functioning have been reported in four uncontrolled descriptive studies with samples ranging from 32 to 108 persons. These studies found that mental health services were associated with improvement in symptoms and functioning among 51 to 78 percent of residents who received services (

11,

12,

33,

34). In contrast, the only randomized controlled study that examined these outcomes found no difference between nursing home residents who received psychogeriatric consultation services and a comparison group that received usual care (

35). This study of 93 residents included ratings of depression and functional outcomes. Although no difference in outcomes was found for the group that received psychiatric consultation services, only a third (27 of 81) of the treatments recommended in the consultation intervention were implemented. The failure of nursing home staff to adopt the written treatment recommendations of external consultants and reviewers was also noted in a study that examined compliance with mandated preadmission screening and annual residence reviews (

36). This review of the records of 523 nursing home residents found that only 35 percent of recommendations for new mental health services were followed.

Several studies have suggested that targeted educational interventions may be successful in changing clinicians' treatment practices. Three uncontrolled descriptive studies of specific training and educational programs found that the programs were associated with lower staff turnover (

37) and improved knowledge and performance by nursing home staff (

30,

38). These studies emphasized the importance of focusing training on the staff members who have the greatest direct contact with residents, such as certified nursing assistants. Two different educational interventions have also been shown to be effective in changing the prescribing practices of physicians in nursing homes. In the first, a decrease in the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications was found in a randomized trial of academic detailing consisting of one-on-one physician education and feedback on prescribing behavior (

39). In the second, lower use of antipsychotics was achieved in a nonrandomized study of nursing staff and physician education in the use of behavioral techniques combined with a protocol for gradual withdrawal from antipsychotic medications (

40).

Several observational studies have reported that mental health services in nursing homes may be associated with better outcomes, including lower rates of hospitalization (

41) and lower use of emergency services (

42). However, none of these studies reported baseline rates of service use for an equivalent period before the intervention. Caution is also warranted in interpreting these results because these studies did not report the methods for determining service use. Finally, an analysis of nursing home survey data suggested that mental health services may be associated with lower mortality rates among nursing home residents with specific psychiatric diagnoses (

43). This descriptive two-year follow-up study of 1987 national nursing home survey data on 4,646 residents reported that among residents with psychiatric disorders, the mortality rate for those who received psychiatric services was 26 percent lower than the rate for those who did not. Notably, this difference was found only for residents with schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders. There were no differences between the groups for other diagnoses, such as depression, after the effects of resident and facility characteristics were controlled for (

44).

In summary, the data on the effectiveness of mental health services in nursing homes are promising but have substantial methodological limitations. Uncontrolled observational studies have reported that one-half to three-quarters of residents who received mental health services improved and that mental health services may be associated with lower rates of hospitalization and lower use of emergency services. However, well-designed controlled studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of mental health services in improving clinical outcomes and reducing use of acute services in nursing homes. Education and training appear to improve staff knowledge and performance and to decrease staff turnover. Innovative educational models are effective in changing physicians' prescribing behavior when ongoing monitoring and direct feedback are provided.

The literature suggests a general consensus that the least effective model consists of traditional consultation-liaison services in which a clinician provides written treatment recommendations on an as-needed basis. This approach appears to be ineffective because of poor treatment implementation, a lack of adherence to written recommendations, and a failure to provide additional services, including ongoing training, administrative consultation, program development, and discipline-specific support.

In contrast, multidisciplinary treatment team approaches appear to be favored in descriptions of preferred service models. However, these studies did not assess the cost-effectiveness of this model. Although researchers have argued that the combined use of physician and nonphysician services, including follow-up, may result in more efficient and effective services, data are lacking. In addition, evidence-based guidelines are needed to ensure that services are provided by qualified clinicians, are medically necessary, and have the appropriate intensity. The lack of cost-effectiveness data is particularly unfortunate in view of the recent controversial findings of the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services, which concluded that 27 percent of mental health services in nursing homes are medically unnecessary (

44). Despite problems in the methods and interpretations of such regulatory studies, they underscore the urgent need to provide empirical support for recommended treatments and service models. Finally, some of the most promising models have focused on improving the behavioral management skills and treatment behaviors of the nursing home staff though training and discipline-specific interventions.