Treatment of mental disorders among older Americans has become a major public health need. The number of people over the age of 65 with psychiatric disorders will more than double by the year 2030, from 7 million in 2000 to 15 million (

1). The past decade has seen dramatic growth in research on the causes and treatments of the psychiatric problems of older adults.

In this article we provide an overview of empirically validated treatments as reflected in systematic reviews of the literature on geriatric mental health interventions. Three types of evaluations of the literature on major geriatric mental health disorders are summarized: systematic evidence-based-practice reviews, meta-analytic studies, and expert consensus statements. Next we summarize major barriers to the dissemination and implementation of these practices. Finally, we describe possible strategies for disseminating and implementing evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care.

An impending public health crisis

At least one in five people over the age of 65 suffers from a mental disorder (

1). By 2030 the number of persons with psychiatric disorders in this older group will equal or exceed the number with such disorders in younger age groups (age 18 to 29 or age 30 to 44) (

1). Despite the growing requirement for mental health services for older persons, there is substantial unmet need. The 1999 Surgeon General's report on mental health (

2), the Administration on Aging's 2001 report (

3), and an expert consensus statement (

1) underscore the need to plan for the provision of services for the growing number of elderly persons with major mental disorders.

Older adults with mental disorders are more likely than younger adults to receive inappropriate or inadequate treatments (

4). Bridging the gap between research and clinical services has been identified as one of the most important priorities in health care (

5,

6). Among the greatest challenges is the "expertise gap" that affects clinicians practicing in routine settings. This gap is the result of inadequate training in geriatric care and a failure to incorporate contemporary research findings and evidence-based practices into usual care.

Evidence-based practices

Many of the underlying principles of evidence-based practice reflect Cochrane's (

7) assertion three decades ago that our limited health care resources should be applied to providing interventions that have proven effectiveness based on well-designed evaluation trials, with emphasis on randomized controlled trials. In this respect, evidence-based practice draws heavily on the use of external evidence to support clinical judgment (

8). Criteria for evidence-based practices define different levels of empirical support based on the quality of the data (

8,

9). The specific criteria vary, but the underlying principles for identifying effective treatments are the same: support must be derived from well-designed controlled trials, and findings must be replicated by different investigators with sufficiently large samples from which results can be generalized (

8,

9).

In the hierarchy of evidence-based reviews of the literature, the highest level is occupied by systematic reviews that evaluate the level of evidence with strict criteria and by aggregate meta-analyses of all relevant randomized controlled trials (

8). The following section provides an overview of the evidence base for geriatric mental health interventions derived from this standard of empirical evidence. This overview of published evidence-based reviews and meta-analyses is not intended to be an exhaustive summary of the research literature but rather a starting point that defines geriatric mental health treatments with proven effectiveness.

English-language review articles that examined the effectiveness of geriatric mental health services were identified for the most common psychiatric problems among older adults: depression, dementia, alcohol abuse, schizophrenia, and anxiety disorders (

10) through searches of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. Disorders for which we were unable to identify evidence-based reviews, meta-analyses, or consensus statements specifically targeting older adults, such as bipolar disorder, were not considered.

Searches were conducted of articles published through the year 2001, including but not limited to the terms evidence-based review, meta-analysis, consensus statement, consensus review, and review article. The evidence-based reviews included were those that systematically categorized studies and applied strict criteria for rating the level of evidence. The meta-analyses included were those that described and applied standardized meta-analytic statistical procedures. Expert consensus statements were included that described a systematic method of obtaining, evaluating, and summarizing expert consensus opinion on effective treatments.

This approach identified eight evidence-based reviews, 26 meta-analytic studies, and 12 expert consensus statements, which are summarized in the five tables. The first two categories were used to determine the evidence base defining effective treatments and services, and the third was included to provide a synopsis of effective treatments and best practices from the perspective of researchers and clinicians.

Geriatric depression

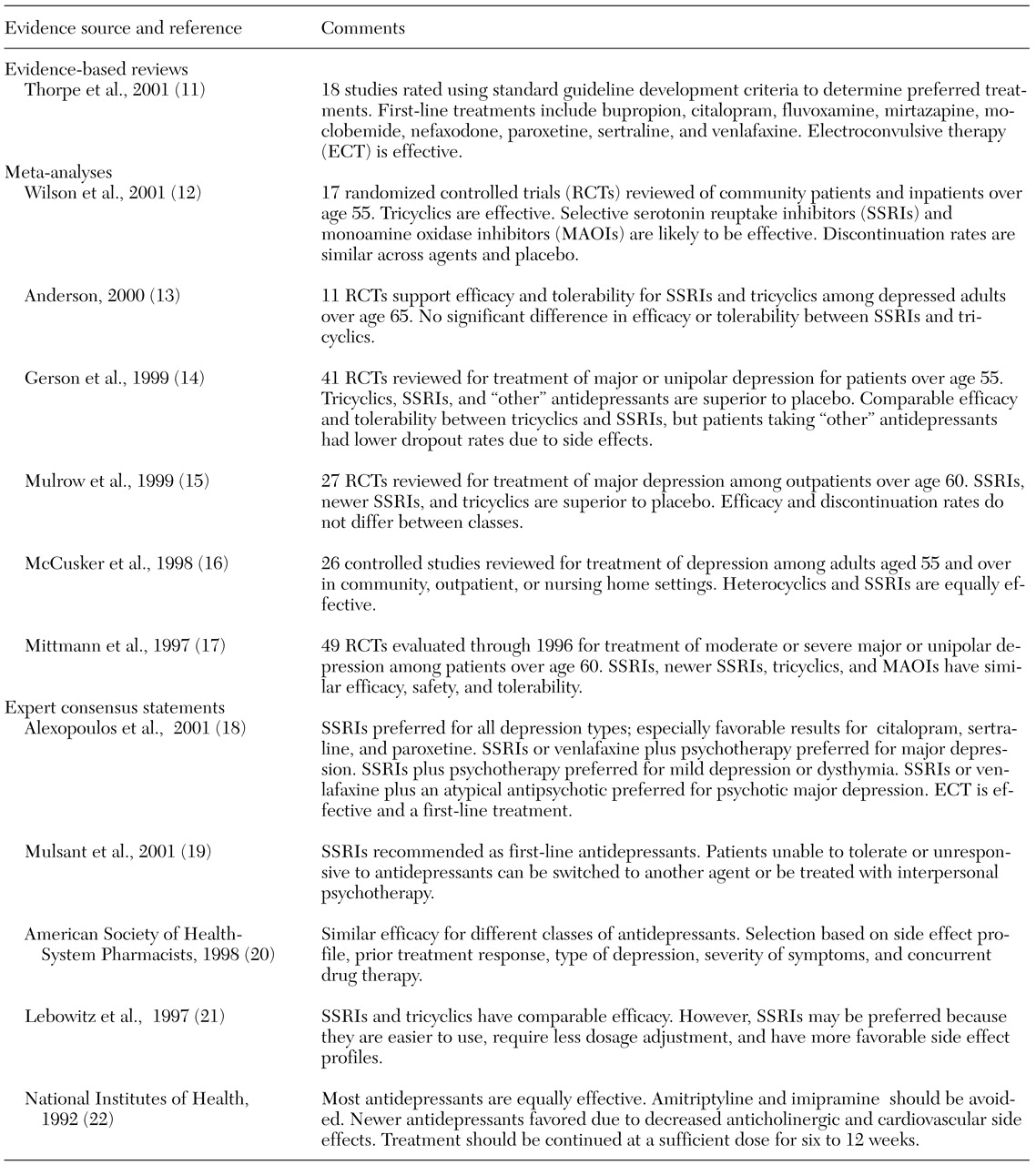

As shown in

Table 1, there is general agreement on the effectiveness of antidepressants for geriatric depression (

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22). In general, more than half of older adults treated with antidepressants experience at least a 50 percent reduction in depressive symptoms (

12). However, a recent meta-analysis of antidepressant studies that included all age groups found that antidepressants offer only a 20 percent (2 points) greater reduction in scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression compared with placebo. This analysis suggests that placebo medication combined with visits by the prescribing physician may account for 80 percent of the effect of antidepressants (

23). In addition, the comparative efficacy and tolerability of different classes of antidepressants remain controversial. Meta-analyses have not shown significant differences between the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the older tricyclic agents in terms of efficacy or treatment dropout from adverse effects. In contrast, expert consensus statements recommend SSRIs as first-line agents for geriatric depression and suggest avoiding tertiary amine antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, imipramine, and doxepin, because of the serious side effects, including cardiovascular and anticholinergic side effects, associated with their use (

18,

19,

20,

21,

22).

Although the meta-analyses did not find a difference in tolerability between SSRIs and tricyclics on the basis of rates of discontinuation due to side effects, clinically significant differences may still be present. For example, common reasons for discontinuing SSRIs include sleep disturbance, gastrointestinal distress, anxiety, headaches, and weight loss, whereas common complications of tricyclic agents include more worrisome side effects, such as postural hypotension and arrhythmia (

14).

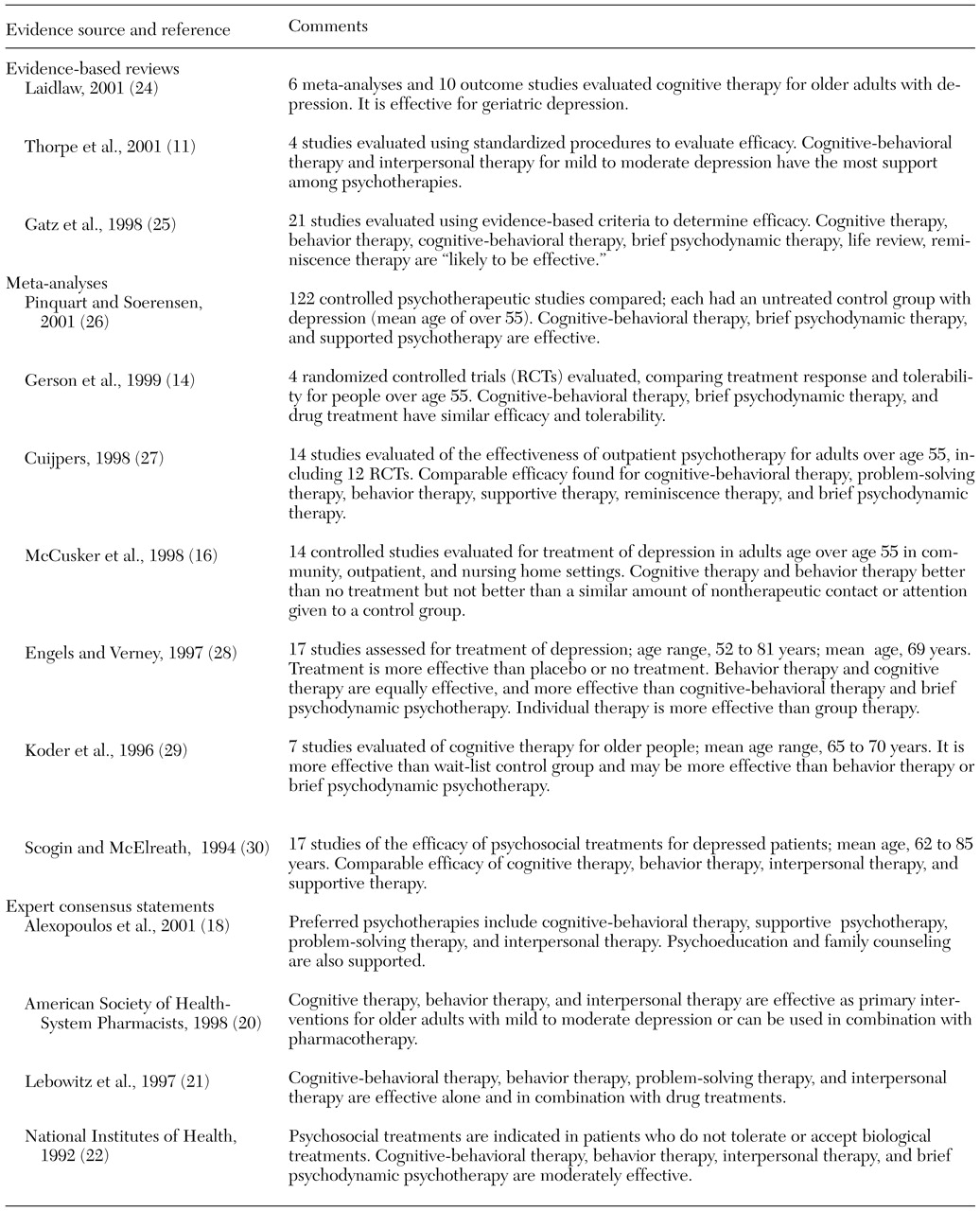

Table 2 summarizes the efficacy of psychosocial treatments for geriatric depression (

11,

14,

16,

18,

20,

21,

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30). In general, cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy have the greatest empirical support for effectiveness in the treatment of geriatric depression. A variety of other psychosocial interventions are likely to be efficacious among older adults, including problem-solving therapy, interpersonal therapy, brief psychodynamic therapy, and reminiscence therapy. Moreover, it is likely that a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions is more effective than either intervention alone in preventing recurrence of major depression, although replication of these findings is warranted (

2,

18). Expert consensus findings recommend the combined use of antidepressants and psychotherapy in the treatment of late-life depression, especially for episodes in which there is a clearly identified psychosocial stressor (

18). Finally, a meta-analysis that compared the rates of response to pharmacological and psychological treatments of depression among patients over the age of 55 found similar effectiveness for antidepressants (tricyclics and SSRIs) and psychotherapeutic interventions (cognitive-behavioral, behavioral, and psychodynamic therapies), although firm conclusions are not possible given the small number of studies (

14).

Evidence-based reviews of interventions for geriatric depression primarily address major depression, with little attention to the treatment of associated conditions such as minor depression or suicidal behaviors. The number of studies addressing the treatment of minor depression among older persons is limited. For example, the results of randomized placebo-controlled studies of SSRIs in the treatment of older adults with minor depression suggest only modest benefits (

31). In addition, little is known about the efficacy of interventions in preventing suicidal behaviors among older adults, even though the rate of suicide among older adults is greater than in any other age group (

32). An evidence-based review of the literature suggests that the only supported preventive intervention for late-life suicide is the identification and effective treatment of depression (

32).

In summary, there is a well-substantiated evidence base supporting the efficacy of antidepressants and cognitive, behavioral, and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the acute and short-term treatment of geriatric major depression. However, caution is indicated in interpreting the results of individual studies that report the superiority of one treatment over another—for example, SSRIs over tricyclic agents—because of the potential sources of bias, which include industry sponsorship of clinical trials, sample selection, and study design.

Dementia

Evidence of treatment effectiveness for dementia can be separated into studies of cognitive symptoms, such as problems with memory, language, and abstraction, and studies of behavioral symptoms, such as agitation, psychosis, and depression.

Cognitive symptoms

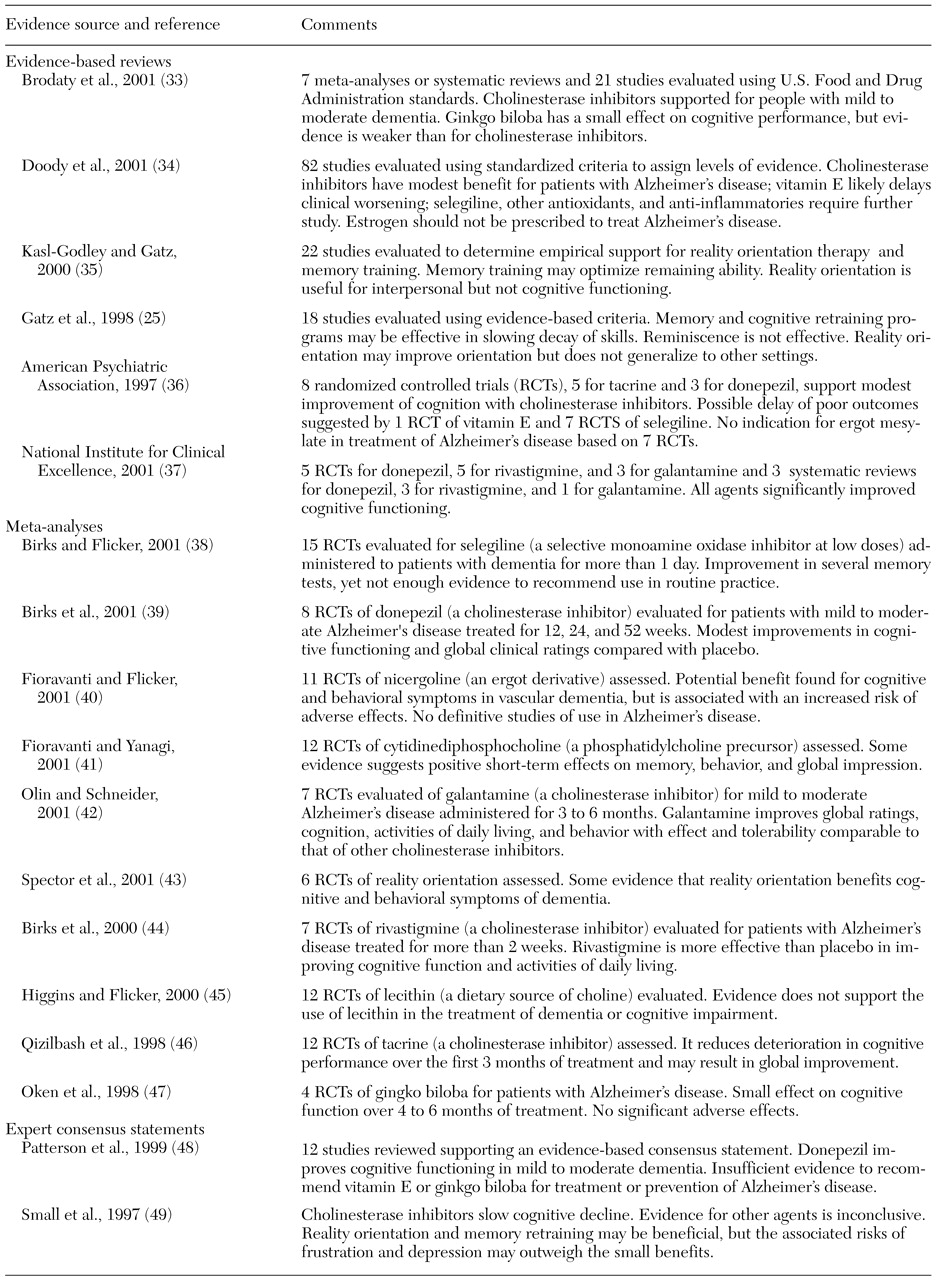

As shown in

Table 3 (

25,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49), for patients with mild to moderate dementia associated with Alzheimer's disease, evidence-based reviews and meta-analyses agree on the effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors compared with placebo in modestly reducing the rate of decline or enhancing cognitive functioning over the course of six to 12 months. In addition, evidence is emerging that cholinesterase inhibitors may be effective in delaying nursing home placement (

50) and that they may improve cognitive functioning in severe Alzheimer's dementia (

51) and in some non-Alzheimer's dementias (

52). Selegiline may also be used, although it has a less favorable risk-benefit ratio and less supporting evidence (

34,

38). In the one placebo-controlled trial of vitamin E, no significant differences were found in cognitive signs and symptoms, although vitamin E minimally slowed progression to institutionalization (

53). The effectiveness of other antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, estrogen replacement, ginkgo biloba extracts, and other agents is not supported by evidence. However, research on the pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's disease is a rapidly advancing field, and a variety of multicenter trials that hold promise for expanding the array of available evidence-based treatments are under way.

In general, psychosocial treatments for the cognitive symptoms of dementia are not effective (

25,

34,

35,

49). A review of the empirical evidence for cognitive retraining programs and reality orientation suggests that these interventions may temporarily improve cognitive, behavioral, and functional skills, but compelling evidence of sustained benefit is lacking (

25,

43).

In summary, despite a traditionally pessimistic view of treatments for dementia, there is an emerging evidence base supporting modest effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors in temporarily decreasing cognitive decline and enhancing cognitive functioning for mild to moderate Alzheimer's dementia over six to 12 months.

Behavioral symptoms

Thirty to 40 percent of persons with Alzheimer's dementia experience behavioral symptoms, including agitation, psychosis, and depression, at some point during the disease (

49). Limited research consisting of individual randomized placebo-controlled studies of conventional antipsychotics (

54,

55,

56) and novel antipsychotics (

56,

57,

58) supports the modest effectiveness of these agents for the treatment of agitation and dementia compared with placebo. However, aggregate analyses of multiple trials of antipsychotics are less conclusive.

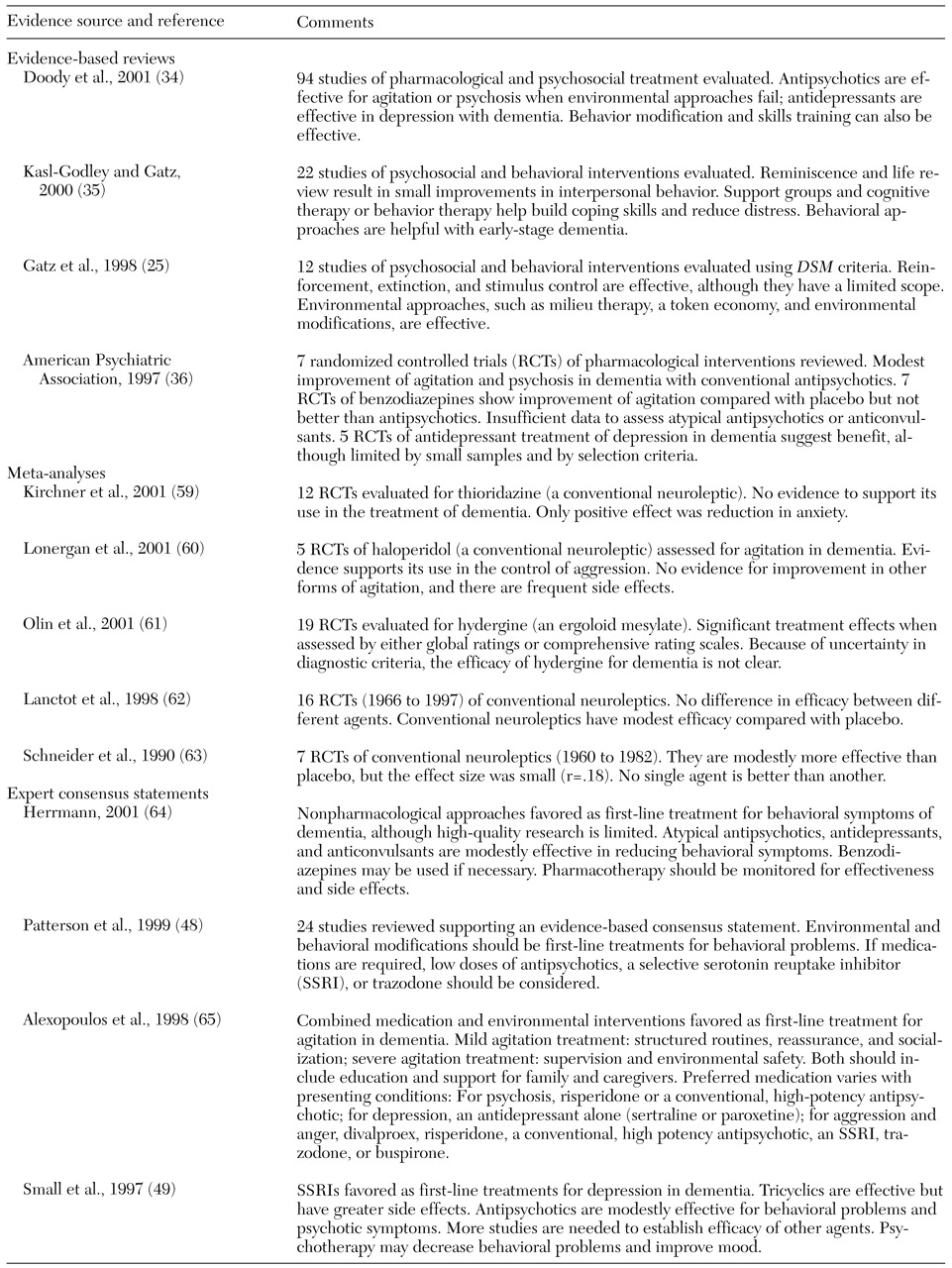

As shown in

Table 4 (

25,

34,

35,

36,

48,

49,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65), evidence-based reviews of pharmacological treatments generally have found that antipsychotic agents are effective in the treatment of behavioral symptoms; however, meta-analyses of studies of single agents or classes of antipsychotics have shown no effect or modest improvement. In contrast, consensus statements widely support the use of antipsychotics and favor the use of novel antipsychotics over conventional agents (

48,

49). In addition, there is accumulating evidence that antidepressants and anticonvulsants are effective in reducing agitation and other behavioral symptoms of dementia (

64).

A limited body of literature suggests that the use of cholinesterase inhibitors can result in changes in behavior and functioning that are detected by both physicians and caregivers, although these findings are based on subanalyses of trials that did not enroll patients with dementia specifically for behavioral problems (

34). In addition, a considerably smaller literature base has examined treatments for depression in dementia. The effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressants for depression in dementia is not supported (

66). However, a recent review suggests that SSRIs may have some benefit (

34).

Behavioral and environmental modifications are also effective in enhancing functioning and reducing problem behaviors associated with dementia. Interventions include light exercise or music (

34,

35,

67), behavioral or social reinforcement, and environmental modifications, such as access to an outdoor area, simulated home environments, and reduced-stimulation units for agitated residents (

25,

67). Psychoeducational training and support groups for caregivers have been shown to delay placement in nursing homes and to decrease caregiver stress (

34).

In summary, empirical evidence supports the value of psychosocial interventions in addressing behavioral symptoms of dementia, but there is less agreement on the effectiveness of antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, and antidepressant agents. However, aggregate analyses of the literature should be interpreted with caution because of the substantial heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria, the inclusion of patients with different types of dementia, the variability in specification of the interventions, and the difficulty of rigorously assessing outcomes in this population.

Finally, it is imperative that clinical assessment of all behavioral and cognitive symptoms includes the differential diagnosis of delirium. The increased risk of delirium among older persons (

68) and the poor prognosis (

69) warrant a careful and systematic assessment of the wide spectrum of possible etiologies and the appropriate treatment of the cause and associated symptoms (

70,

71).

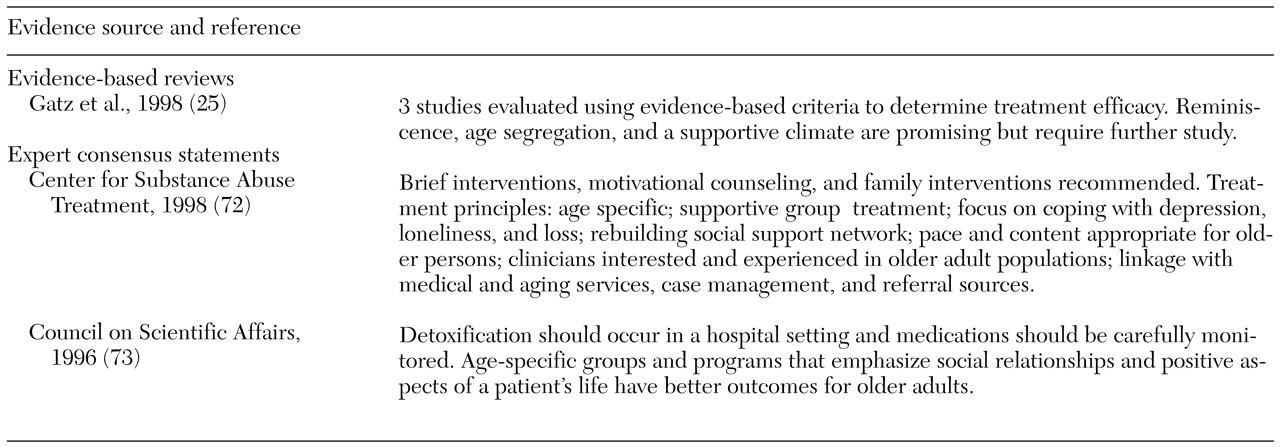

Alcohol abuse

Consensus statements (

72,

73) and general reviews (

74,

75) provide little endorsement for the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for geriatric alcohol abuse. In contrast, psychosocial interventions are likely to be effective for older persons with alcohol use disorders (

Table 5). Promising treatment components include separate treatment groups for older persons, supportive and nonconfrontational treatment approaches, and group or individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (

25). In particular, there is compelling evidence that brief cognitive-behavioral interventions are effective in treating late-life alcohol abuse (

76).

In summary, age-specific, nonconfrontational, brief motivational, and cognitive-behavioral therapies show promise as interventions for alcohol abuse in geriatric populations.

Schizophrenia

We found no evidence-based reviews or meta-analyses of treatment for schizophrenia among older persons. Nonetheless, a consensus statement on late-life schizophrenia (

77) and general reviews of the treatment of psychosis in the elderly population (

78,

79) endorsed the view that antipsychotic medications are effective.

For example, reviews have compared the relative merits and potential complications of conventional antipsychotic agents (

80,

81) and novel antipsychotics (

80,

81,

82,

83,

84) for the treatment of psychosis among older persons. Clinical reviews have reported that older persons are more susceptible to adverse effects of conventional antipsychotics, including parkinsonian side effects and tardive dyskinesia (

80,

81,

82). Recent research on the use of novel antipsychotics among older adults is largely limited to open-label uncontrolled studies (

85,

86,

87,

88) and a small number of controlled trials (

89,

90). Overall, the reports and reviews suggest that atypical antipsychotics should be considered as first-line agents in the treatment of schizophrenia among older persons. Recent systematic reviews comparing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of conventional agents and atypical agents other than clozapine among younger patients did not find evidence of significant differences in efficacy (

91,

92). However, atypical agents have been shown to be safer for older persons in terms of motor side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (

93).

Data on psychosocial interventions for older adults with schizophrenia are lacking. The literature on the effectiveness of psychosocial treatments for geriatric schizophrenia is limited to a single controlled pilot study suggesting the potential benefits of a combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and skills training (

94). A consensus statement supports residential alternatives rather than long-term hospitalization and the provision of social and vocational skills training, community support programs, and psychoeducational programs for family members (

77). However, the lack of data supporting these recommendations is noted, which underscores recommendations for studies addressing this research gap (

1).

In summary, the efficacy of antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia among older persons is supported by individual studies and general reviews; however, no evidence-based reviews or meta-analyses have been published.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is one of the most common mental health problems affecting older adults (

2). However, there is a paucity of research on the effectiveness of available treatments. General reviews of the literature provide a limited perspective on the effectiveness of treatments for geriatric anxiety disorders (

2,

95,

96,

97,

98). These reviews report that benzodiazepines are the most frequently prescribed antianxiety medication among older persons and recommend consideration of pharmacological alternatives. However, few double-blind placebo-controlled trials have been conducted with this population (

96).

Despite preliminary results suggesting possible benefits of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of geriatric anxiety disorders, conclusive findings are not available (

25,

96,

99). Other promising but inadequately researched psychotherapy treatments include cognitive-behavioral group therapy, cognitive restructuring, individual behavioral therapy, and supportive group psychotherapy (

2).

In summary, the limited empirical evidence confirms the efficacy of treatment with conventional antianxiety agents, while acknowledging the potential problems associated with benzodiazepines. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has the greatest support among psychosocial interventions.

Models of service delivery

In addition to research on treatments for specific disorders, a limited body of literature has examined the effectiveness of various models of service delivery. A review of the evidence base found the greatest support for community-based, multidisciplinary, geriatric mental health treatment teams (

100). Promising although inconclusive data were found on the effectiveness of hospital-based geriatric psychiatry consultation-liaison services. In contrast, no randomized controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of geropsychiatric inpatient units or day hospital programs. Finally, the effectiveness of geriatric consultation services to nursing homes is inconclusive. One review (

101) found a randomized controlled trial that showed no significant differences in clinical outcomes between patients who received psychiatry consultation services and those who received usual care.

In summary, empirical evidence supports the effectiveness of community-based, multidisciplinary geriatric mental health treatment teams.

Implementing evidence-based practices

Challenges

Despite evidence supporting the efficacy of a variety of interventions for geriatric mental disorders, the implementation of these interventions in usual care settings is limited. Reasons for this limited implementation include organizational barriers, bias and ageism among providers, inadequate and discriminatory financing of mental health services for older persons, and lack of collaboration and coordination between providers (

2,

3). These barriers are further complicated by national shortages of medical and social service professionals who have training and expertise in geriatric mental health care (

1,

3). The different priorities, capacities, and levels of expertise between primary care, long-term care, and specialty mental health providers in the areas of aging and mental health care further complicate implementation of evidence-based treatments (

3,

102).

In summary, there is a substantial shortfall in the provision of psychiatric interventions in usual-care settings. Nearly half of older adults with a recognized mental disorder have unmet needs for services (

103).

Implementation research

An evolving practice research literature describes methods that may effectively improve the implementation and use of evidence-based practices by mental health providers who serve older adults in usual care settings.

Primary care. Most older persons who receive mental health care are treated by primary care physicians (

102,

103). Yet the many demands of primary care present substantial challenges to such care (

2). Older persons with psychiatric illnesses are more likely to receive inappropriate pharmacological treatment and less likely to be treated with psychotherapeutic interventions than younger primary care patients (

104).

Considerable attention has been focused on educational efforts to improve screening for and treatment of depression by primary care providers, yet the failures of these traditional approaches as a means of improving physicians' practices are well documented. For example, providing practice guidelines to clinicians without additional incentives or interventions aimed at changing practices is ineffective in changing their behavior (

105,

106,

107). Although physician education is necessary, it alone is not effective in enhancing guideline-concordant care. Grand rounds presentations and physician conferences, the mainstay of conventional continuing medical education, are generally ineffective by themselves (

108). Educational interventions that actively involve the learner and use multiple techniques are most effective in changing physicians' behavior (

106).

For example, academic detailing, which consists of brief one-on-one educational sessions coupled with provider-specific feedback on treatment practices, is effective in influencing the practice behavior of primary care physicians (

109). Changes resulting from this novel educational intervention include short-term improvement in rates of detection of the target disorder (

110) and a decrease in prescriptions for medications that are not indicated (

109).

Other effective interventions include changing the process of care within a physician's office. For example, interventions to change the system have been found to result in significant improvements in quality of care and patient outcomes (

107). Such interventions include combinations of physician and patient education, care management, and improved coordination among mental health and primary care providers. Simple but effective interventions for facilitating the process of care also include tools that monitor patients' progress, such as severity measures (

111) and systems for scheduling routine follow-up visits (

112). Care management can also help improve treatment adherence and facilitate monitoring of treatment response. In this model, the geriatric psychiatrist or other specialist supervises care managers and provides limited consultation to the primary care or general psychiatrist providers.

Finally, another approach is integration of services through collaboration between providers of specialty mental health care and primary care in a common setting. A mental health clinician who provides collaborative care is situated in the primary care practice setting and coordinates assessment and treatment services with the medical provider (

113).

Long-term care. Observational studies suggest that mental health consultation services in nursing homes may be associated with better outcomes for residents (

101). However, few randomized controlled studies of these programs have been conducted. Training in assessment and management of behavioral problems has been shown to reduce turnover of clinical staff (

114) and improve the knowledge and performance of nursing staff (

115,

116). Educational outreach interventions are also effective in changing the clinical practice behavior of prescribing physicians when education and feedback is provided on an individual basis (

117). In addition to evidence-based interventions, a series of guidelines specific to the treatment of major mental health disorders have been developed to assist nursing home professionals in caring for older adults with mental illness (

118,

119).

Specialty services in the community. There are few data on improving the adherence of community-based specialty mental health providers to empirically based geriatric mental health practices. General mental health clinicians lack training in basic assessment and treatment of the mental disorders of aging. System change interventions that support clinicians in the use of assessment and treatment planning toolkits have been shown to improve clinicians' adherence to standardized geriatric assessment practices (

120). However, data are lacking on interventions aimed at improving the use of evidence-based treatments in community settings.

Strategies

The gap between research findings on empirically supported treatments and clinical practice suggests the need for an organized strategy to facilitate the implementation of geriatric evidence-based practices in usual care settings. Key elements of an approach to implementing evidence-based practices emphasize the involvement of stakeholder groups, including administrators, clinicians, consumers, and families (

121). Implementation guides for mental health authorities and administrators are designed to address the reorganization of practice environments, procedures, incentives, and reimbursements to incorporate empirically supported treatment practices. In contrast, materials for clinicians are designed to accommodate different levels of expertise and to provide decision support technologies and treatment guides that facilitate the use of evidence-based treatments in routine practice. Finally, the adoption of empirically supported treatments depends on buy-in by consumers and their families, who will ultimately decide to follow or reject recommended treatments. Multimedia educational materials that are sensitive to the preferences and needs of consumers and their family are important in supporting the acceptance and use of evidence-based treatments.

In summary, a successful strategy for implementing evidence-based mental health interventions is grounded in a systems approach, combined with the development and dissemination of easy-to-use implementation kits and well-described procedures for changing practices (

121).

Conclusions

This overview of research defining evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care suggests that there is a need to address the profound gap between research findings on effective treatments and the current availability of such treatments for older persons with mental disorders.

However, several caveats are indicated in considering such an effort. First, identification of evidence-based practices should be considered as a starting point for improving the quality of care. In essence, evidence-based practices define "the floor" in quality and should not be confused with best, optimal, or promising practices. Second, there is a misperception that only randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, or systematic reviews can constitute the evidence base. Evidence-based practice is based on careful and appropriate use of the findings of the best relevant studies, accompanied by an appreciation of the limits of the existing data. In some instances, the best studies include randomized controlled trials, whereas in other situations, nonrandomized outcome studies or case reports may constitute the evidence base.

An additional and important consideration involves inherent limitations in the methodology used to identify evidence-based practices, which may result in the overly conservative exclusion of informative studies or may group studies together without adequate attention to important differences between studies. For example, common problems affecting meta-analyses and evidence-based reviews include small samples and lack of power, heterogeneity of samples, lack of interchangeable instruments, lack of extractable data, different definitions of outcomes, differences in the quality of research and the duration of the studies, and reliance on statistical rather than clinical significance (

63,

122).

Furthermore, evidence-based reviews and meta-analyses are largely dependent on data from randomized controlled trials that compare a single well-defined intervention with a placebo or other control. Thus they are less suited to inform more complex decisions, such as choosing the next step after a series of failed interventions for a treatment-refractory condition or making the most effective use of the many different possible combinations of agents. The large number of potential combinations and sequences of treatments and the large number of different clinical conditions and comorbid physical conditions make it virtually impossible to support all clinical decisions with data from randomized controlled trials (

8).

One approach to addressing gaps left by standardized evidence-based reviews and meta-analyses is the use of expert consensus guidelines. Recently published guidelines on the pharmacotherapy of depression among older patients are an example of treatment recommendations based on an aggregate analysis of independent ratings by experts on the appropriateness of various treatment options (

18). In addition, the guidelines for major psychiatric disorders developed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (

36,

70,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127) provide treatment recommendations that are assigned one of three levels of confidence based on clinical consensus. With the exception of the guidelines on dementia, the APA guidelines are not age specific, suggesting that future initiatives may be undertaken to develop clinical guidelines specific to older adults.

In general, guidelines and treatment algorithms can provide the clinician with a practical and comprehensive summary of recommendations. However, caution is warranted. Guidelines should be evaluated on the basis of their level of support from systematic reviews of the evidence, because the consensus of experts may inadvertently incorporate the bias of specialties and disciplines and may misrepresent treatment effectiveness or side effects (

128,

129).

Finally, despite advances in clinical expertise and research, a substantial body of literature chronicles the failure of conventional educational approaches and the limited impact of disseminating treatment guidelines. Meaningful changes in the quality of care require innovative technologies that use research findings focused on organizational and provider change. This challenge is compounded in a system of geriatric mental health care that includes different organizations and sources of financing and treatment by providers from different disciplines. Despite these challenges, there is a clear and urgent demographic imperative to address the emerging public health problem of the mental disorders of aging. It is time for geriatric psychiatry to take up the mantle of evidence-based practices and translate research findings into the mainstream of clinical treatment for older Americans.