Intensive case management has become a popular community treatment in many countries for persons with severe mental illness (

1). However, its efficacy remains in doubt. Some authors claim that intensive case management causes a marked decrease in inpatient bed-days, better engagement in and satisfaction with services, and improved relationships and social networks (

2). Others claim that intensive case management fails to improve clinical outcomes for hard-to-treat patients (

3) and that it has not been shown to produce significant advantages over standard case management in clinical and social outcomes (

4,

5).

It has become a commonplace practice to assess patients' satisfaction with community psychiatric services such as assertive community treatment and intensive case management (

6,

7,

8). However, a criticism of some patient satisfaction questionnaires is that they provide only general measures of satisfaction, which tend not to capture particular areas of dissatisfaction and therefore provide overly positive results of a particular service (

6). Domain-specific measures seem better at picking up dissatisfaction than general satisfaction assessments (

9). Notable, too, is that the appropriateness of satisfaction as a concept for use in evaluating service provision has been questioned (

10).

In that light, we focused in this study on patients' perceptions of their relationship and contact with their case managers. Few case management studies have examined patients' perceptions of the merits of intensive case management. We sought to examine two hypotheses. The first was that patients receiving intensive case management would perceive more benefits than patients receiving standard case management. The second hypothesis was that patients' perceptions of their care and their case managers would be influenced by demographic, clinical, and social variables.

Methods

Sample selection

Our investigation included patients from the UK700 Case Management Trial, a study comparing the efficacy of intensive case management and of standard case management (

4). Intensive case management was defined as a reduced caseload, ranging from ten to 15 patients per case manager. Standard case management was defined as a caseload of 30 to 35 patients per case manager. Staff members for the two services were broadly comparable. Both services offered community mental health teams. Most case managers were mental health nurses, but some were occupational therapists, mental health support workers, and psychologists. The levels of training and skill of the staff members were similar for the intensive case management and standard case management groups (

4). The primary difference between the two services was caseload size.

As part of the UK700 Trial, after a series of baseline assessments of clinical and social variables, 708 patients with psychosis were randomly assigned to receive intensive or standard case management. Patients were recruited from four inner-city mental health services (King's College Hospital, St. Mary's Hospital, St. George's Hospital, and London and Manchester Royal Infirmary) serving populations with substantial social deprivation (

1,

4).

The criteria for entry into the UK700 Trial were age between 18 and 65 years; presence of a psychotic illness of at least two years' duration, identified by hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorder according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (

11); a minimum of two psychiatric hospital admissions, one within the previous two years; absence of organic brain disorder; and absence of a primary diagnosis of substance abuse.

Study design

Patients were assessed with a battery of instruments at baseline, at the end of year 1, and at the end of year 2. For the purposes of this study, we developed a structured questionnaire to measure patients' perceptions of case management. This questionnaire was included in the year 2 interview conducted between 1997 and 1998 at two of the four centers (King's College Hospital and St. George's Hospital).

Instruments

The patients' perceptions questionnaire included nine items addressing patients' perceptions of their case managers and the care received during the preceding 24 months. It took five to ten minutes to complete.

The number of days of hospitalization for a psychiatric disorder was assessed with a modified World Health Organization life chart (

12) for the preceding 24 months. Clinical status was assessed with the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (

13), in which the severity of 65 items of psychopathology are rated for the preceding week on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Negative symptoms were measured with the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (

14), which comprises 24 items, also referring to the preceding week.

The Lancashire Quality of Life Profile (

15) was used to assess quality of life. It contains 100 questions about quality of life and life satisfaction in nine domains: work and education, leisure and participation, religion, finances, living situation, legal and safety, family and social relations, health, and self-conflict. Item scores were summed for each domain, and a mean satisfaction score was computed for the domains. Item scores were rated as present or not present. The satisfaction score was rated by the patient on a scale of 1 to 7 from "things cannot be worse" to "things cannot be better."

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (

16) was adapted to assess social disability during the preceding month. The Disability Assessment Schedule was summarized by using the mean of all scored items. The Camberwell Assessment of Need (

17) measured met and unmet needs in 22 areas of clinical and social functioning, as perceived by the patient.

Patients' satisfaction with psychiatric services was recorded on a self-report questionnaire (

18), rating nine items of satisfaction on a four-point scale.

Analysis

Factor analysis was conducted and varimax rotation performed for the nine items of the patients' perceptions questionnaire to identify which items were correlated with each other. The optimum number of factors was determined by using the scree plot and was considered with the interpretability of the associated factors. A factor score based on the regression method was derived for each group of items. The factor scores could be interpreted as a subscale of the scores of the grouped items. A constant of five was added to factor scores to make all numbers positive. Factor scores were then transformed by using natural logs for a more normal distribution.

Three main analyses were conducted on the transformed factor scores. The first included t tests to examine perception scores in relation to patient and case manager sex (male versus female), ethnicity (white British versus African-Caribbean and first generation versus second generation), center (King's versus St. George's), and allocation (intensive versus standard case management). Additional t tests were performed to test the differences between male and female case managers and patients' clinical and social variables. Further analyses were conducted to assess interactions. For these analyses, one-way analysis of variance was used to examine whether the effect of case managers' sex on patients' perceptions differed as a function of patients' sex and ethnicity.

Finally, multiple linear regression was used to examine the association between patients' perceptions (using transformed factor scores) and patients' clinical and social variables. The analysis controlled for patients' age, sex, ethnicity, and education; case managers' sex; allocation; center; and corresponding baseline scores. Additional analyses were conducted by using one-way analysis of variance to assess whether the effect of patients' clinical and social variables on their perceptions of services varied as a function of their case management group. All analyses were conducted with SPSS (version 8.0.2, 1998) and STATA (version 6.0, 1999).

Results

Patients' demographic and clinical characteristics

Overall, 339 participants completed the year 2 follow-up assessments at two centers as part of the main trial (189 at St. George's and 150 at King's). Of these, 225 patients completed the additional perceptions questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 66.4 percent.

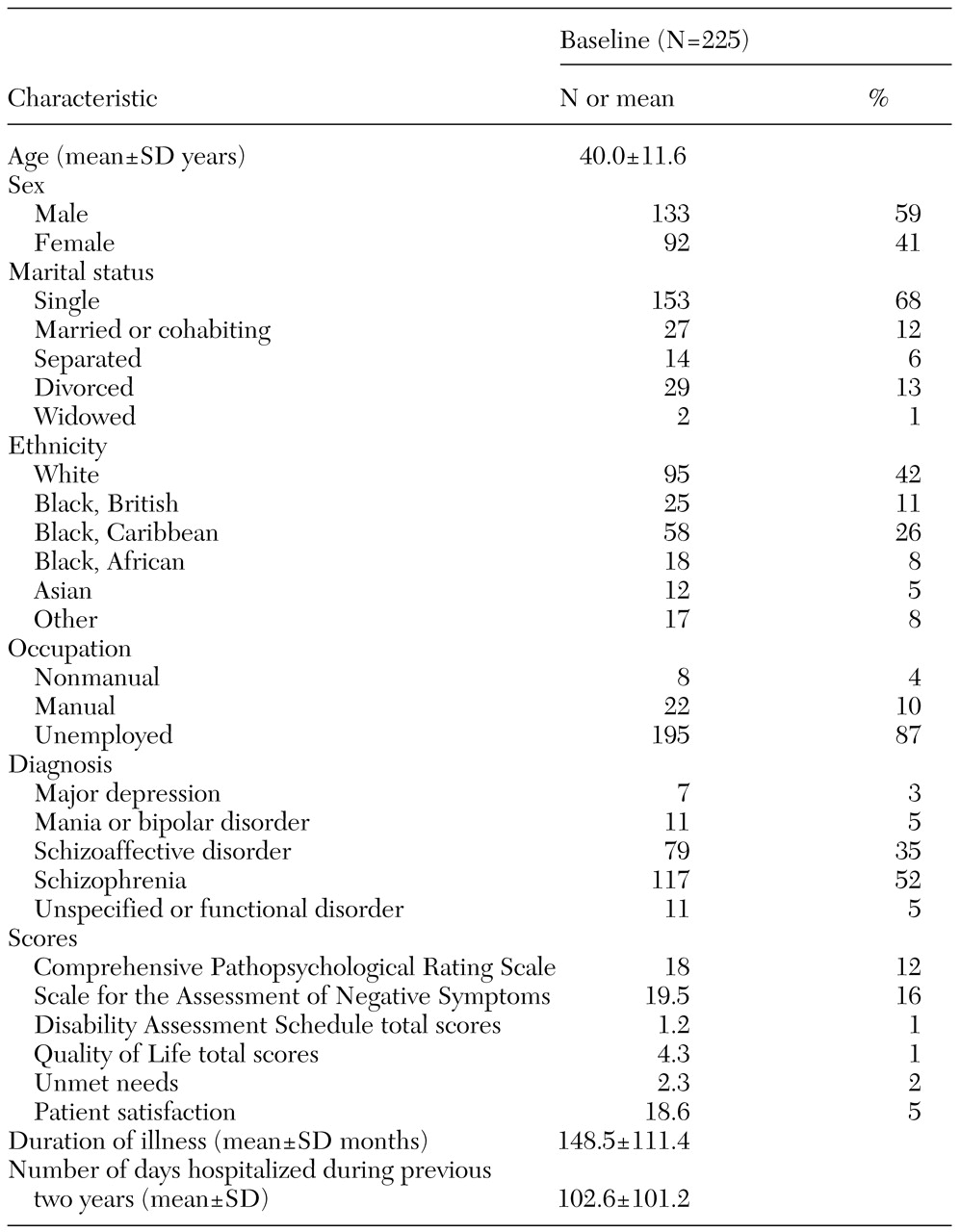

Table 1 summarizes the patients' demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline. About 60 percent of the participants were men, and the patients' mean age was 40 years. More than two-thirds were single and never married, and 12 percent were currently married. The majority of the patients were unemployed (87 percent). Most had diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and about 13 percent had other diagnoses. The median duration of illness was 120 months, or ten years.

Participants were compared with eligible patients who did not complete the patients' perceptions questionnaire. There were no differences between these two groups in terms of age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, and diagnosis.

Factors associated with perceptions of case management

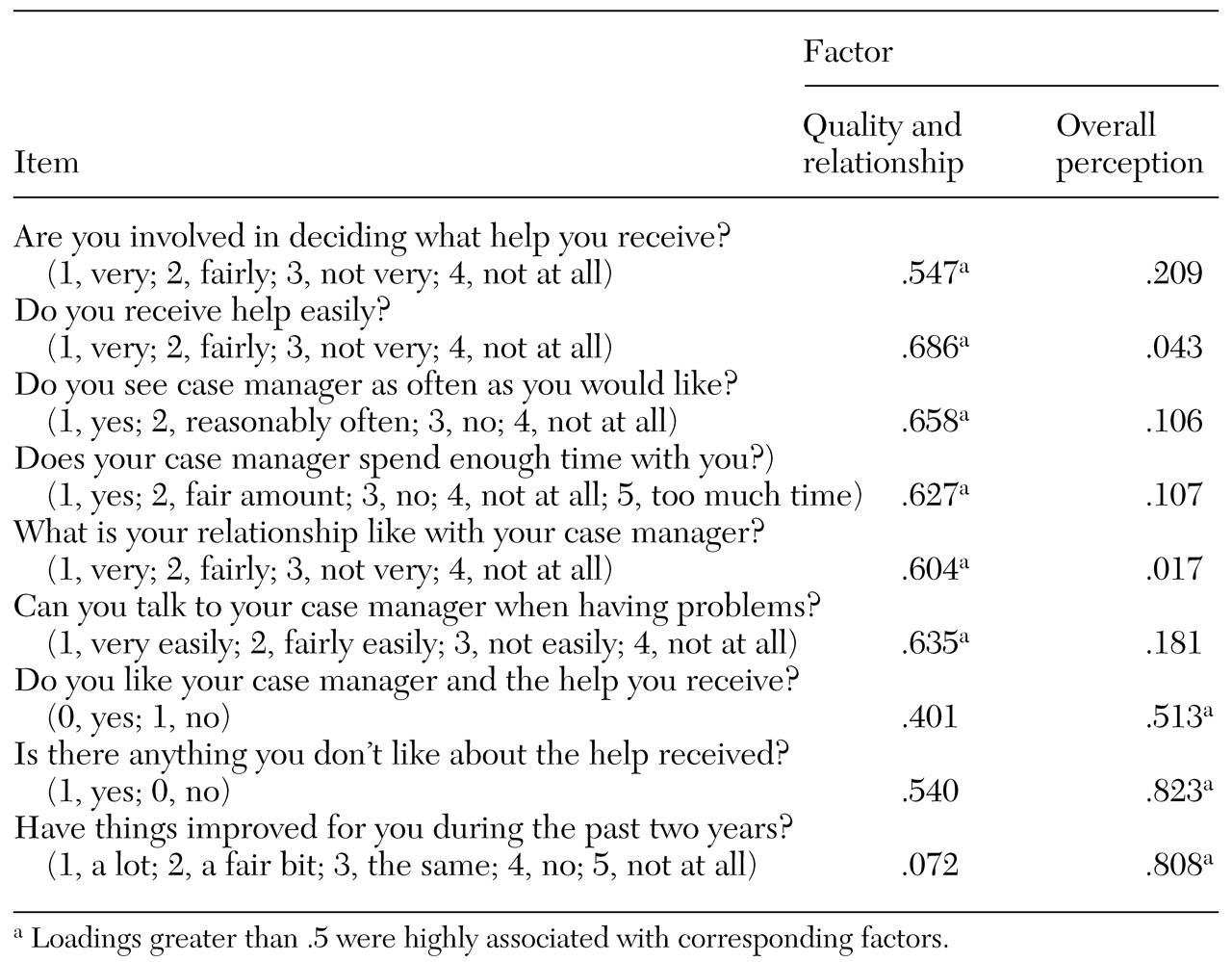

Two main components of perceived benefits of case management emerged from the factor analysis: perceived quality of care and relationship with case manager, which we abbreviated to "quality of care," and overall perception of case management, which we abbreviated to "overall perception."

Table 2 presents the rotated component matrix and the loadings for each factor. The loadings represent the extent to which the item is determined by the factor; for example, .547 is highly associated with factor 1.

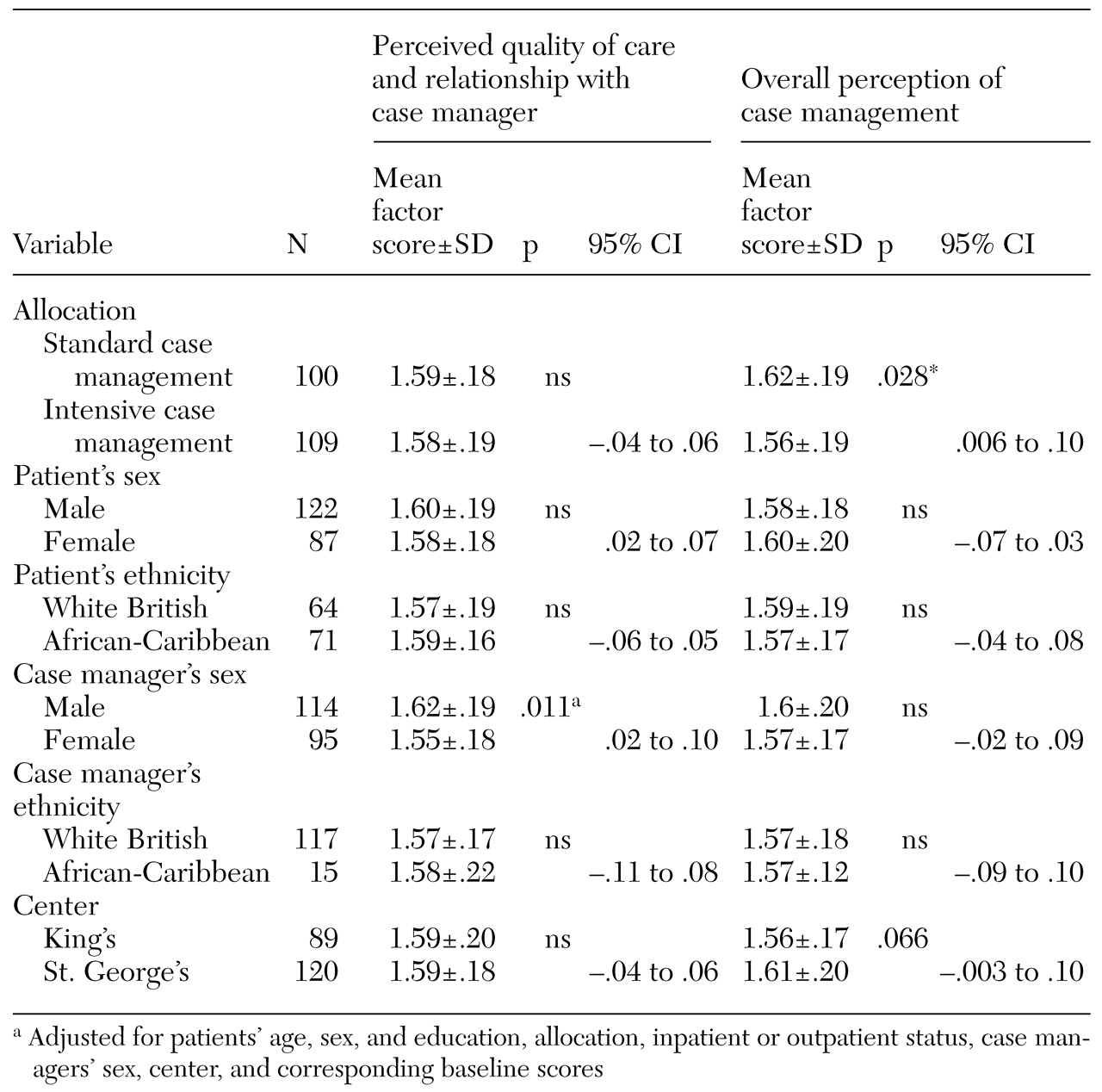

Table 3 lists the associations between patients' perceptions and various characteristics, including type of care allocated. Higher factor scores indicate fewer perceived benefits. Intensive case management was significantly associated with better overall perception compared with standard case management (p=.028) but not with better perceived quality of care. Patients' sex, patients' ethnicity, and case managers' ethnicity had no significant association with the way in which case management was perceived.

A significant positive relationship was observed between having a female case manager and perceived quality of care (p=.011). This positive association was not dependent on whether patients were male or female, nor was it dependent on their ethnic group. Patients with female case managers also tended to have a more positive overall perception of case management, although this was not significant. Closer examination indicated that there was no relationship between having a female rather than a male case manager and patients' clinical and social variables.

Quality of care and clinical and social variables

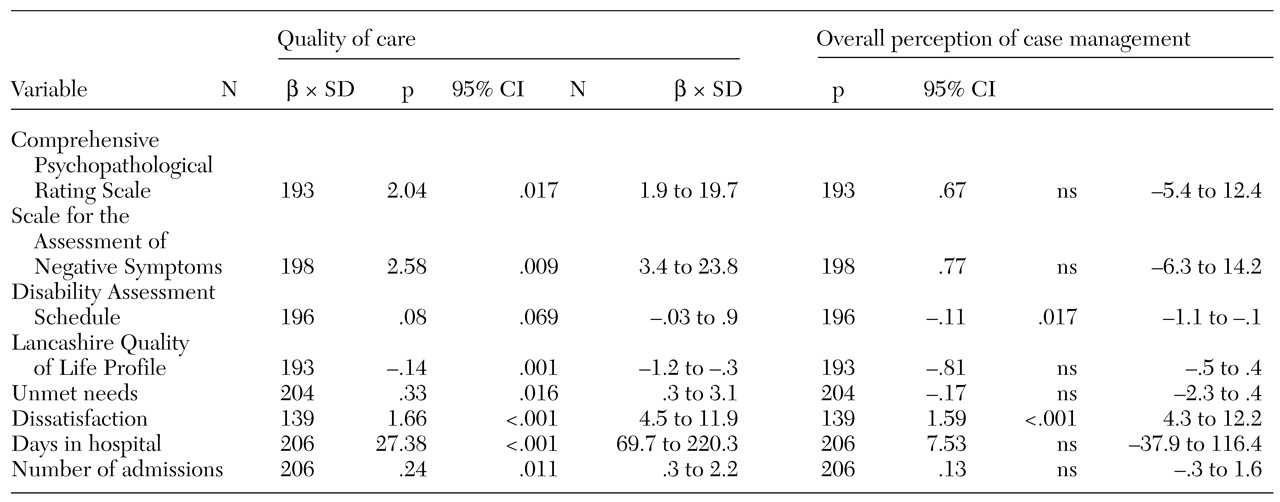

Table 4 lists the linear associations between perceived quality of care and clinical and social factors. Scores on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale and on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms were positively associated with perceived quality of care after adjustment for patients' age, sex, and education; allocation; status; case managers' sex; center; and corresponding baseline scores (p=.017 and p=.009, respectively). After adjustment, the number of days hospitalized was significantly associated with perceived quality of care (p<.001). The number of admissions was also significantly associated with perceived quality of care (p=.011), although not as strongly as the number of days hospitalized. Adjusted quality of life and dissatisfaction with services were again strongly associated with perceived quality of care (p=.001 and p<.001, respectively), but adjusted Disability Assessment Schedule scores were not. Considering that the data are cross-sectional, it is impossible to establish the causal direction of these significant associations. However, the findings indicate that patients' perceived quality of care was worse for those who had more severe symptoms, more hospitalization, and a worse quality of life.

The effect of case management intensity on the association between clinical and social variables and perceived quality of care was minimal. The relationship between social and clinical variables and perceptions of case management did not differ significantly between intensive and standard case management groups, with the exception of unmet needs (F=5.27, df=1, p=.023).

Overall perception of case management and clinical and social variables

By contrast, few of the clinical and social measures examined were associated with patients' overall perception of case management (

Table 4). After adjustment, only the Disability Assessment Schedule and satisfaction with services were significantly associated with overall perception of case management (95 percent confidence intervals, −1.1 to −.1, p=.017, and 4.3 to 12.2, p<.001, respectively).

Case management intensity had no effect on the association between patients' clinical and social variables and their overall perception of service.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that patients who were receiving intensive case management had a better overall perception of the service they received than those receiving standard case management. However, there was no significant difference in perceived quality of care between the intensive and standard care groups, despite the greater contact and accessibility of intensive case managers. Female case managers were regarded more favorably than male case managers in terms of perceived quality of care. Patients' sex and ethnicity had no effect on this association.

Some highly significant associations were found between perceived quality of care and clinical and social variables after adjustment was made for a number of potential covariates. More days of hospitalization and poorer quality of life were particularly associated with poorer perception of care. However, the confidence intervals for number of days hospitalized are very wide, so this finding needs to be interpreted with caution. Overall, these significant associations between perceived quality of care and clinical and social variables did not differ by the intensity of case management, except for unmet needs.

Implications

The perception of better quality of care from female case managers may suggest that both male and female patients prefer female case managers. However, patients who had female case managers did not have better clinical and social outcomes than those who had male case managers.

Given the cross-sectional nature of our data, we cannot determine the direction of the association between patients' perceptions and their clinical and social statuses. Whether patients who are doing well have a better perception of the care they have received or vice versa is not clear; further study using a longitudinal design is needed to clarify the association. It is possible that patients who perceive their relationships with their case managers and their quality of care to be good are more cooperative with treatment and more likely to engage with services, although this is highly speculative. Nevertheless, the relationship between patients and their case managers is an important consideration in any assessment of patients' satisfaction with services. Similarly, if severity of symptoms influences the way patients perceive the services they receive, this, too, must be considered in any evaluation of patients' satisfaction with services.

Limitations

The perceptions schedule was designed for the purposes of this study to focus on certain factors not usually covered by general satisfaction questionnaires. Some items of the perceptions questionnaire overlap with satisfaction questionnaires, but we also sought to assess patients' perceptions of their contact and interaction with their case managers.

It was difficult for assessors to remain blind to patients' case management allocation because of safety issues, and some bias may have been introduced in rating patients' perceptions. Similarly, patients were not blind to the treatment group to which they had been allocated (intensive or standard case management), and patients' responses may have been influenced by this.

Two years is a long period for patients to consider when asked about their case management, and it is possible that their responses were based on more recent experiences. Some patients, particularly those receiving standard case management, had different case managers during the trial period. These patients were asked to provide a general overview of their care during the two-year period. Finally, our sample included only adults with established psychoses in inner-city areas, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

On the whole, the patients in our study with severe psychotic illnesses who were receiving intensive case management had a more positive overall perception of their care than did the patients who were receiving standard case management. However, no differences were observed between the groups in perceived quality of care. Patients with female case managers perceived that they had received better care than did patients with male managers. We found patients' clinical and social status to be strongly related to their perceived quality of care, although these associations did not vary overall with case management group.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Pak Sham, M.R.C.Psych., for statistical advice and Norman Urquía, M.Sc., for advice on constructing the perceptions questionnaire.