In mental health services, the goal of performance monitoring is twofold: to improve health status by stimulating improvements in the quality of health care (

1) and to ensure that patients are receiving appropriate, adequate, and continuous care. Health care report cards such as the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) have been used as central tools for performance monitoring. HEDIS and other performance monitoring systems use standardized sets of measures from administrative databases that help both purchasers and consumers of health care compare performances of different managed care plans (

2). These performance monitoring systems have been used both to quantify performance and to improve quality of care (

3). However, the number of performance measures that are readily available for mental health services is limited, and new performance measures for assessing the quality, continuity, and intensity of care need to be developed.

There are three criteria for a good performance measure. First, the measure must be readily available—that is, the information that is needed to measure performance must be comprehensible and easily accessed. Second, the performance measure must have face validity—that is, it should make clinical sense. Third, the measure must be associated with desirable outcomes, such as greater access to care, shorter inpatient stays, and greater connectivity between outpatient and inpatient care.

One aspect of care that could be evaluated through performance monitoring systems is whether patients who are admitted to a hospital were receiving outpatient care before admission. Using such connectivity between outpatient and inpatient care as a performance measure makes clinical sense, because the fact that a patient has received preadmission outpatient treatment indicates at a minimum that some effort has been made to prevent hospitalization and that the system has made a commitment to continuous care for the patient. The fact that a patient has received preadmission care may suggest the presence of interventions or bridging strategies, which have been shown to predict successful transitions between inpatient and outpatient treatment settings (

4).

Researchers have commonly addressed linkages between inpatient and outpatient psychiatric services by focusing on the transition from inpatient to outpatient care (

5,

6,

7,

8). In this study we used administrative data from a large national sample of veterans who had been discharged from psychiatric inpatient units at 122 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals to examine the relationship between preadmission care and three outcomes: length of inpatient stay, access to aftercare 30 days after discharge, and rehospitalization at 14, 30, and 180 days after discharge.

Methods

Sample

The sample comprised all 37,852 psychiatric inpatients who had been discharged from 122 VA Medical Centers across the United States between October 1, 1997, and March 31, 1998. The data on inpatient hospitalization came from the VA's Patient Treatment File, and the data on outpatient service use came from the VA's Outpatient Care File. Together these files track all service delivery in the VA Health Care System. They are used routinely for performance monitoring of VA mental health programs (

9). The VA's institutional review board waived the requirement to obtain written informed consent from the study participants.

Data analysis

To prevent duplication, data were extracted on the first inpatient stay for each patient during the study period. Unique identifiers—scrambled social security numbers—were then used to merge the data from the two sources. The primary independent variable of interest was preadmission care, or the level of mental health outpatient service use in the month before admission. We measured preadmission care in three ways: as a continuous variable, describing the total number of outpatient visits in the month before hospitalization; as a spline variable, based on five discrete levels of care; and as a binary variable, describing whether or not the patient had received any outpatient care before the index hospitalization. These exploratory analyses allowed us to determine whether specific levels of care were associated with better outcomes.

There were three dependent variables of interest: length of inpatient stay in days, access to postdischarge aftercare 30 days after discharge, and rehospitalization at 14, 30, and 180 days after discharge. Potential confounding covariables we considered were age, gender, race, marital status, diagnosis of schizophrenia, diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder, VA service-connected disability, drug or alcohol problems, dual diagnosis, medical illness, the distance from the veteran's home to the nearest VA or non-VA hospital, and whether the outpatient care received in the month before admission represented a new contact preceded by five months without VA outpatient mental health care services or was received as part of more continuous involvement in outpatient care.

We began the statistical analyses by examining the bivariate relationships between the outcomes of interest and the potentially confounding covariables. Covariables that were significant in these analyses at an alpha of .05 were then controlled for in later multivariable models. Multivariate models were then used to model preadmission care as a linear function, as a five-level spline function, and as a binary function regressed against the outcomes of interest with significant covariables controlled for. Multivariable ordinary-least-squares linear regression models were used to regress preadmission care and length of stay. Multivariable unconditional logistic regression was used to regress access to postdischarge aftercare 30 days after the index admission and readmission at 14, 30, and 180 days against preadmission care.

Interaction variables were also evaluated to test for possible differences in subgroups of the sample. Each interaction term was included in a separate regression with all significant covariables controlled for. Because of these multiple comparisons, we used a Bonferroni correction to adjust the significance level by dividing the initial alpha of .05 by the number of comparisons (eight in total), resulting in a significance level of .005. SAS version 6.12 was used for all the analyses (

10).

Results

The patients' mean±SD age was 50±11.7 years. The patients were predominantly white (N=24,164, or 63.8 percent) and male (N=35,782, or 94.5 percent). A total of 8,701 patients (23 percent) were single, and 10,169 (26.9 percent) were married. The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia (9,017 patients, or 23.8 percent), followed by alcohol problems (4,781 patients, or 12.6 percent) and drug problems (2,157 patients, or 5.7 percent). More than a third of the patients (15,550 patients, or 41.1 percent) had a dual diagnosis of substance abuse. A majority of patients had received outpatient services the month before they were hospitalized (23,373 patients, or 61.8 percent). The participants' mean±SD inpatient length of stay was 20±43 days. A total of 987 patients (2.6 percent) were new to the system, meaning that their first visits of the previous six months occurred during the month preceding the admission.

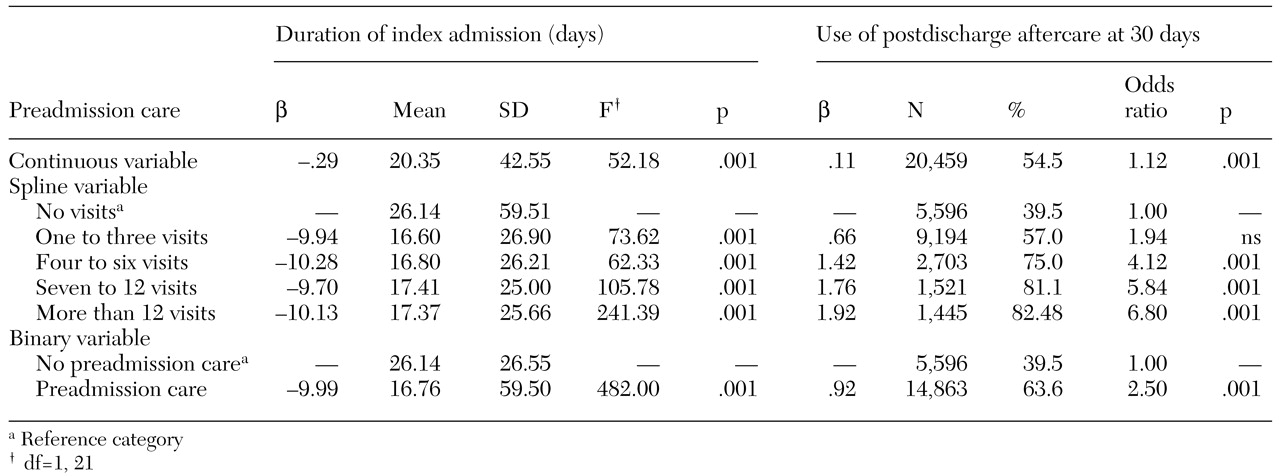

The results of the multivariable analyses for the first two dependent variables are summarized in

Table 1. The duration of the index admission was significantly shorter among patients who had received previous outpatient care. Patients who had made at least one outpatient visit before hospital admission had a mean±SD length of stay of 16±1.2 days, compared with 26±1.1 days for patients who had not received preadmission care, a significant difference of almost 63 percent. However, careful examination of the parameter estimates for all three preadmission care variables—continuous, spline, and binary—indicated that receipt of previous treatment alone was more important than the actual number of preadmission care visits.

As also shown in

Table 1, receipt of preadmission care was associated with a greater probability that the patient had received postdischarge aftercare at 30 days after the index admission. However, unlike with length of stay, the probability of having received postdischarge aftercare at 30 days increased with the number of preadmission care visits. For example, patients who had made seven to 12 preadmission care visits were nearly seven times as likely as other patients to be using postdischarge aftercare at 30 days, and patients who had made only one to three visits were only about two times as likely to be using postdischarge aftercare at 30 days.

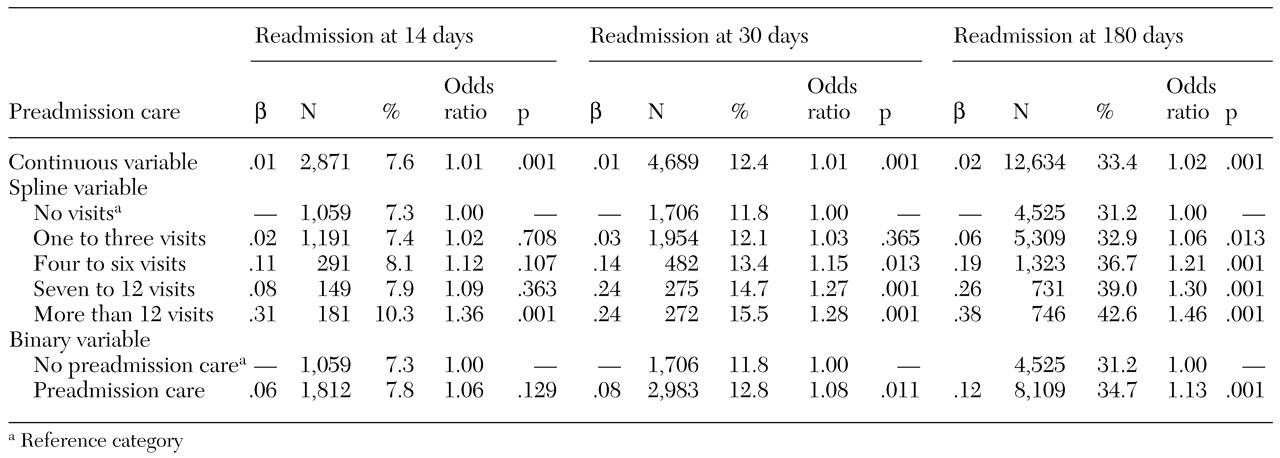

Data on the relationship between preadmission care and readmission 14 days after discharge, 30 days after discharge, and 180 days after discharge are summarized in

Table 2. The patients who had received preadmission care were slightly more likely to have been readmitted by any of these three time points. The probability of readmission by each time point also increased slightly with the number of preadmission care visits.

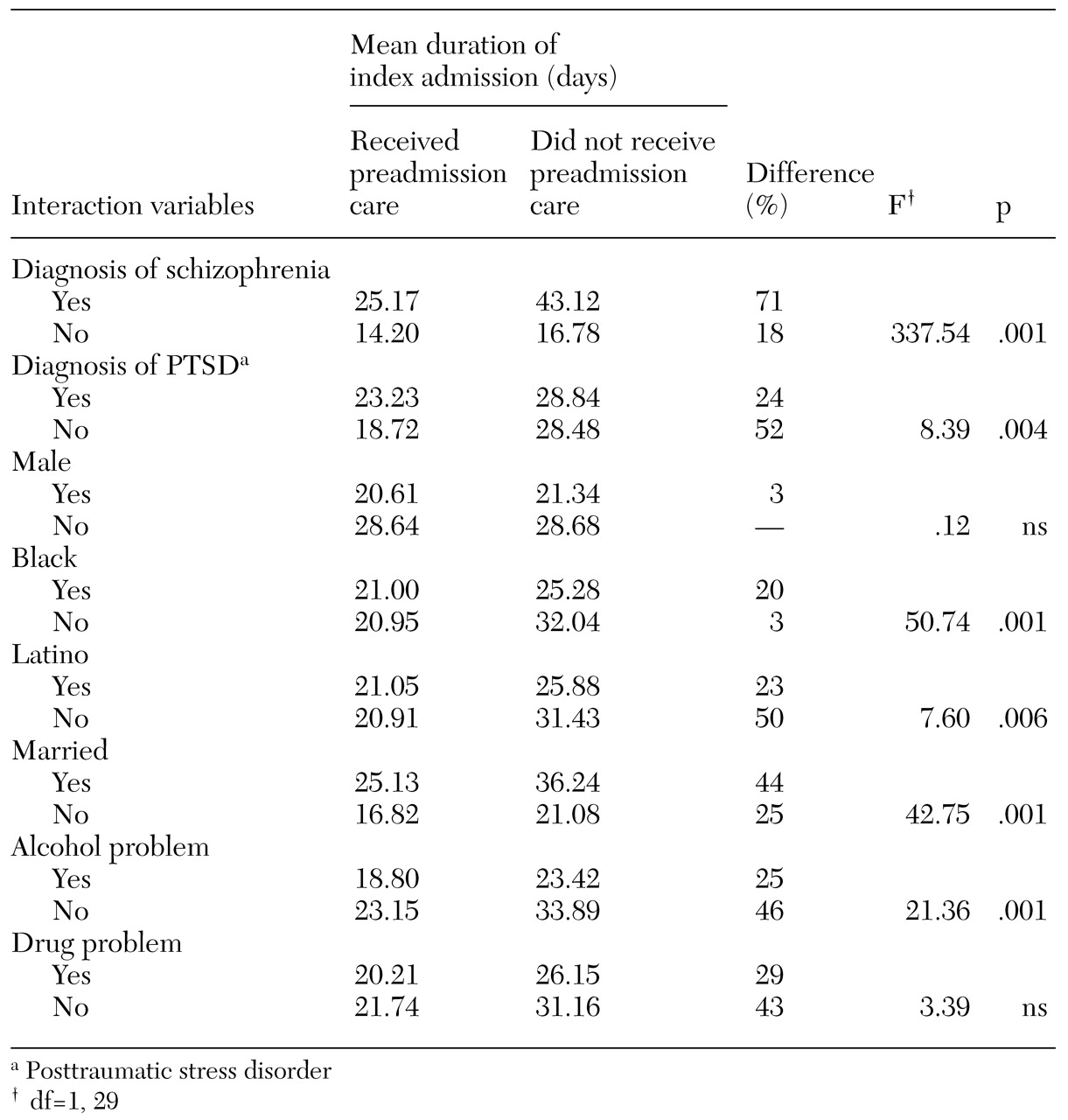

The results of a series of interaction analyses are summarized in

Table 3. After a Bonferroni correction, the significance level was set at .005. It is clear from this analysis that some groups benefited more from preadmission care than others. Patients with schizophrenia who had received preadmission care had the largest benefit: their mean length of stay was 71 percent shorter than that of those who did not receive preadmission care, compared with an 18 percent shorter stay among patients who did not have schizophrenia. White patients who had received preadmission care demonstrated a significantly greater benefit than other patients: their mean length of stay was 50 percent shorter than those who did not receive preadmission care, compared with a 20 percent shorter stay among African Americans and Latinos. Finally, preadmission care had less of an effect among patients who had an alcohol problem than among those who did not.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate a new performance measure for mental health services, preadmission care, which could be used to monitor the performance of mental health systems on the basis of available administrative data. Our findings suggest that preadmission care can be readily assessed with administrative data and that patients who receive preadmission care have shorter stays and are more likely to use postdischarge aftercare but may be slightly more likely to have been readmitted by 14, 30, or 180 days after discharge.

We initially identified three criteria for a good performance measure. The measure must be readily available, it must make clinical sense, and it must be associated with desirable outcomes. As a performance measure, preadmission care appears to readily satisfy the first two criteria in that the data on preadmission care are readily available in administrative databases within the VA system and that such care reflects greater continuity and availability of crisis intervention services.

Preadmission care was associated with two of the three desirable outcomes we investigated: shorter stay and greater likelihood that a patient would be engaged in postdischarge aftercare 30 days after the index admission. These findings are not surprising: if a patient initiated a treatment visit before hospitalization, he or she might require a shorter hospitalization. It also makes clinical sense that patients who received some type of care before hospitalization might be more likely to still be using services 30 days after hospitalization.

Although it seems clinically plausible that patients who had received preadmission care were less likely to be rehospitalized because emerging problems could be addressed during their continuous outpatient treatment, we found instead that preadmission care was associated with a slight increase in probability of rehospitalization. It is possible that patients who receive greater levels of preadmission care are more severely ill than those who receive lower levels and that they are therefore at greater risk of rehospitalization, or that patients who receive preadmission care have a greater affinity for treatment than patients who do not receive preadmission care and thus are more likely to seek further care of any type. Unfortunately, we do not have data to evaluate these possibilities.

It is also possible that patients who had received preadmission care were rehospitalized to prevent further deterioration. If this were true we would expect the patients who had received preadmission care, while more likely to be rehospitalized, to have shorter rehospitalization episodes. To test this hypothesis we examined all patients who were readmitted to determine whether those who had received preadmission care had shorter readmission stays than those who had not received preadmission care. Our hypothesis was confirmed in that the patients who had received preadmission care and who were readmitted had significantly shorter readmission stays than patients who had not received preadmission care (p<.01).

The primary strengths of this study were its use of a large sample and the diversity of locations of the VA hospitals across the United States. The study's primary weaknesses fall into three categories: the ambiguous clinical meaning of "preadmission care," nonequivalent comparison groups, and limited generalizability.

Although it is possible that preadmission care reflects the quality of care because it reflects an ongoing commitment of the service provider, as we have hypothesized, it is also possible that preadmission care is a problematic indicator in that some service providers do not provide hospital treatment to people who are not already in their system, instead referring them to inpatient services elsewhere as a matter of policy. Such providers would provide high levels of preadmission care but under a service model in which continuity of care is restricted.

The comparison group may not have been equivalent because of lack of random assignment, which raises the possibly that important covariables were omitted from our analysis. Although the list of potential covariables is extensive, three potentially important covariables that were not available are severity of illness, the quality of the therapeutic alliance (whether a patient had an established relationship with his or her clinician before admission), and the patient's general affinity for treatment.

The direction of any bias inherent in these variables is unclear. For example, we might hypothesize that patients who receive preadmission care are more likely to be severely ill than those who do not. However, if this were true, it could lead these patients to seek either more outpatient care as a result of their direct need for care or less outpatient care because they are less capable of seeking care. Such ambiguities of interpretations are often unavoidable when administrative data are used.

The VA health care system is different from other health care systems, both in the characteristics of the patients it treats and in the characteristics of the system itself. Because these differences may limit the generalizability of our findings, they deserve further comment.

The VA treats mostly men, all of whom have served in the military (about 20 percent of the U.S. population). If men are less likely than women to comply with their medication regimens, the relationship between receipt of preadmission care and outcomes such as risk of rehospitalization could be different for women than for men. However, there is little evidence of such differences.

Furthermore, each state typically has a limited number of VA hospitals. Patients who do not live close to a VA hospital may choose to obtain regular outpatient care from a local provider and go to the VA only for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, because the cost of such care is high and thus makes the trip worthwhile. Under this scenario, the likelihood of preadmission care may be lower and the likelihood of readmission higher.

However, we controlled for distance between a patient's residence and the nearest VA hospital in our analyses, so distance from a VA hospital is unlikely to have confounded the results. Furthermore, the results of several recent studies suggest that cross-system use of non-VA psychiatric care by veterans is not common (

11,

12,

13).

These findings would benefit from replication in other mental health systems and from inclusion of additional baseline and clinical outcome data. A follow-up study that maximizes internal validity would randomly assign patients seeking emergency treatment to either receive preadmission care or be directly hospitalized. Preadmission care deserves further study as a potential mental health quality indicator.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Service Integrated Network 1 Mental Illness Research and Clinical Center and a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH-15783-23). The authors thank Rani Desai, Ph.D.