Access to high-quality medical care is a problem for people with schizophrenia. Patients with chronic mental illness in general (

1,

2), and those with schizophrenia in particular (

3,

4), have high rates of underdiagnosed and undertreated medical problems. A recent study indicated that people with schizophrenia who had a physical illness were less likely to be admitted to a hospital during the early, less severe phases of the illness and more likely to be admitted when the disease was more advanced and more severe (

5). People with schizophrenia who are hospitalized because of a myocardial infarction are less likely than members of the general population to receive state-of-the-art medical care (

6). The number of older people with schizophrenia in the community is increasing (

7), and, because medical illnesses become more common and more debilitating with age, the treatment of comorbid medical illnesses among older people with schizophrenia is becoming an important health care issue (

8).

Serious mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, are much more common among homeless people than in the general population. Investigations have consistently found higher rates of substance abuse, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression among homeless people than in the general population (

9,

10,

11). Schizophrenia is about ten times more common among homeless individuals than in the general population (

12).

Both schizophrenia and homelessness are associated with elevated mortality rates. The age-adjusted mortality rate for people with schizophrenia is about two times that of the general population (

13,

14,

15); cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death among people with schizophrenia (

16,

17). Homeless people have been reported to have a mortality rate 3.5 times as high as that of the general population (

18). Elevated mortality rates among homeless people have been observed in studies of several large cities (

19,

20,

21). Among homeless people with schizophrenia, mortality rates 3.7 times as high as in the general population have been reported (

19).

We sought to assess the health status of middle-aged and older homeless people with schizophrenia and to document the primary and preventive health care they received. To our knowledge, no published studies have evaluated medical comorbidity in older homeless people with schizophrenia or have reported rates of physical examinations or preventive screening among individuals with schizophrenia. Our study setting was St. Vincent de Paul Village, a homeless services agency and shelter in San Diego, California. We used a systematic review of charts from the shelter's free medical clinic, which also provides psychiatric services, to obtain data on the primary and preventive health care received by shelter residents with schizophrenia. We hypothesized that people with schizophrenia would receive less primary and preventive health care and have fewer documented medical problems than a comparison group treated for major depression.

Results

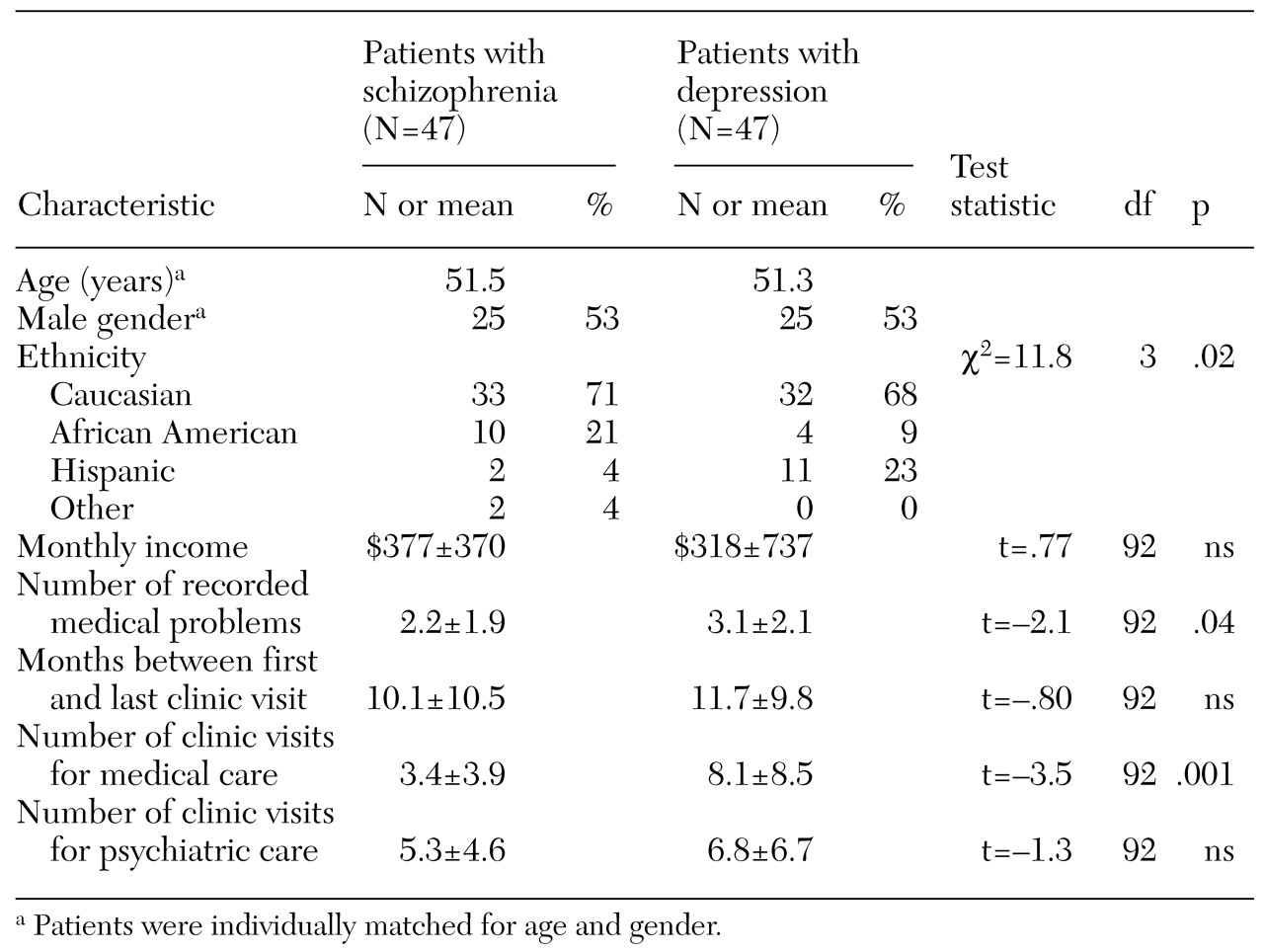

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the two age- and gender-matched groups. The two groups differed in ethnic composition. Shelter residents who received treatment for schizophrenia were more likely to be African American, and those treated for depression were more likely to be Hispanic. The number of psychiatric visits and the duration of treatment at the clinic were also similar. However, patients with schizophrenia had fewer documented medical problems and fewer medical visits. No differences in mean income were noted between the two groups.

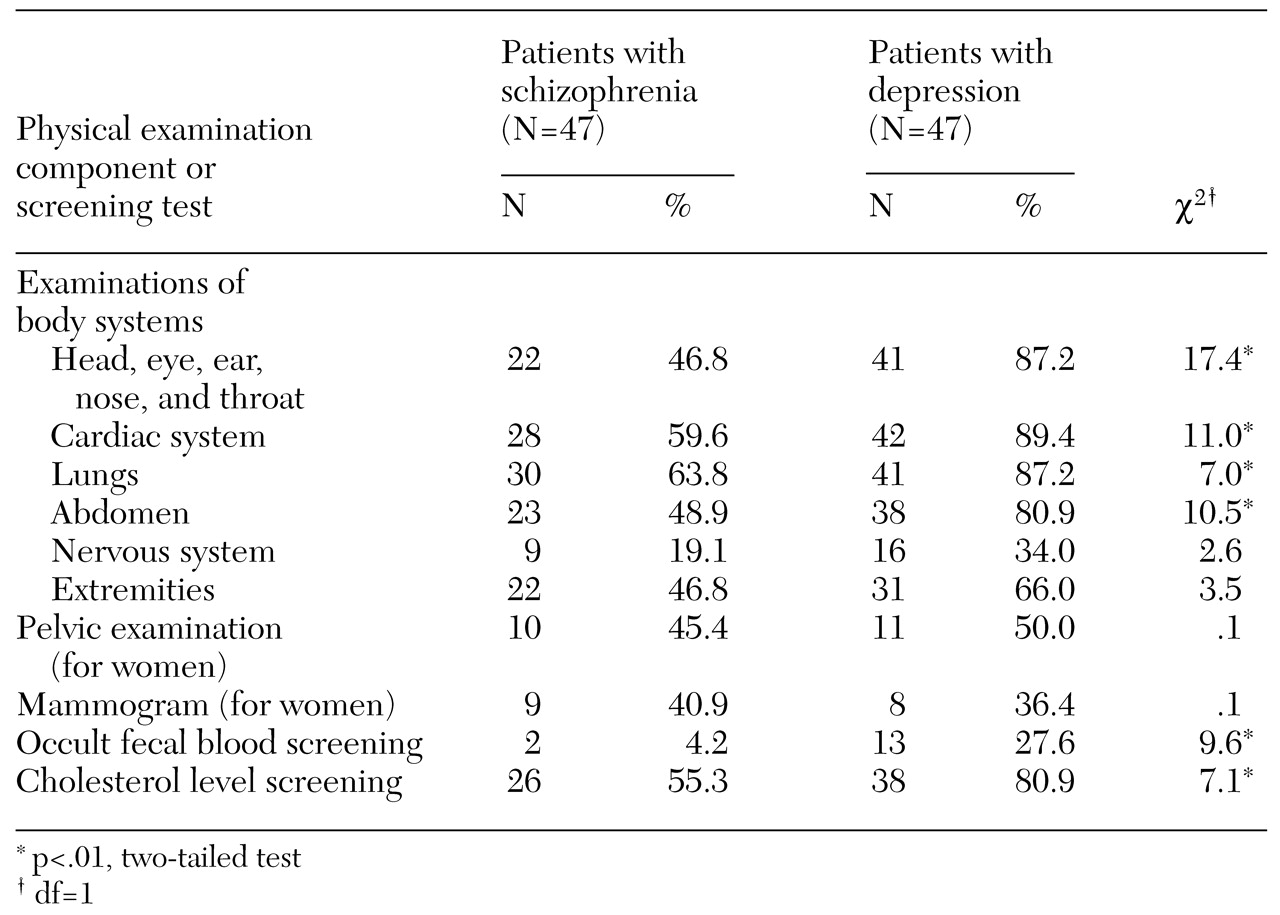

Patients with schizophrenia were less likely than those with depression to receive most components of the physical examination, including examination of the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat and cardiac, lung, and abdominal examinations (

Table 2). For women, there was no difference between groups in the rates of pelvic examination or mammogram. Screening tests for colon cancer and cholesterol levels were documented less often for people with schizophrenia.

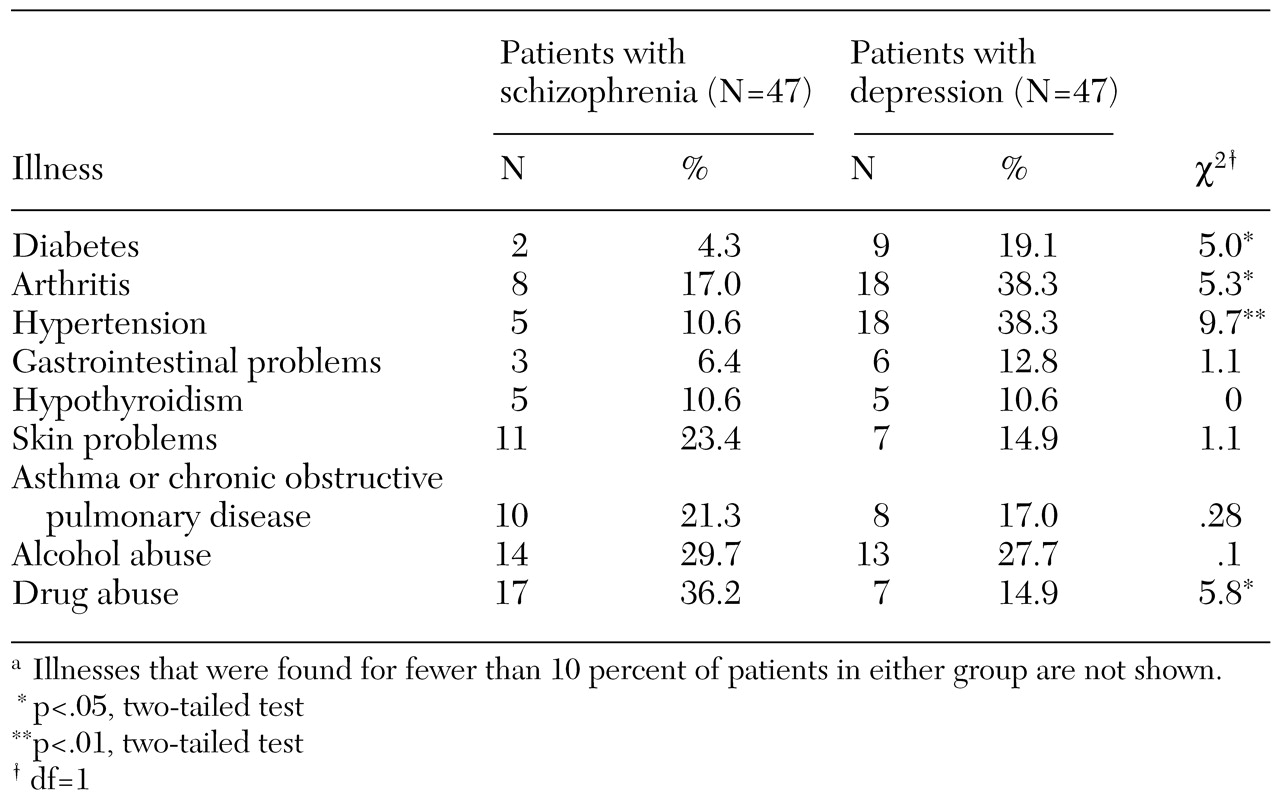

Patients with schizophrenia were less likely to have recorded chart diagnoses of diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension (

Table 3). The frequency of several other common chronic medical conditions, including asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, skin problems, and hypothyroidism, was similar for the two groups. Problems that were uncommon in either group—found for fewer than 10 percent of either group—are not listed in

Table 3. The rates of drug abuse were higher among patients with schizophrenia. The rates of alcohol abuse were similar for the two groups.

The difference between ethnic groups in psychiatric diagnoses was unexpected. However, ethnic differences in rates of mental disorders were not the focus of this study. Additional studies with larger samples are needed to determine whether this finding is valid. Because of the difference in ethnicity between the two groups, the statistical comparisons were repeated with data from only the Caucasian patients (33 patients in the schizophrenia group and 32 in the major depression group). This reanalysis showed no changes in the direction of the differences between the groups, although the smaller sample reduced the level of statistical significance for some variables. The p values for the comparisons of rates of cardiac and abdominal examinations and of a diagnosis of hypertension changed from <.01 to <.05. The p values for the comparisons of rates of lung examination and of a diagnosis of substance abuse changed from <.05 to <.1. Finally, the differences in the rates of diabetes and arthritis, in the number of medical problems, and in the rate of cholesterol screening became nonsignificant.

Discussion

In this chart review study of middle-aged and older homeless people living in St. Vincent de Paul homeless shelter in San Diego, shelter residents with schizophrenia received less primary and preventive health care than an age- and gender-matched comparison group with major depression. The patients with schizophrenia also had fewer documented chronic medical illnesses. This finding is interesting in light of the fact that no differences between groups were found in the number of psychiatric visits or the duration of treatment.

Our findings of less primary and preventive health care and fewer documented medical problems among older homeless people with schizophrenia are consistent with earlier reports of high rates of undiagnosed medical illnesses among people with schizophrenia (

20,

21). Taken together, the findings of fewer documented medical problems, less health care, and higher rates of mortality strongly suggest that all people with schizophrenia, not just those who are homeless, are at risk of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of medical illnesses.

The elevated mortality rates from cardiovascular disease among people with schizophrenia also suggest that this group is less likely to receive primary and preventive health care in the early and silent stages of a disease (

16,

17). For example, the rate of hypertension has been reported to be 40 percent lower among people with schizophrenia than in the general population, but the reported rates of admission for end-stage complications of hypertension, including cardiomyopathy and pulmonary edema, are 1.8 and 1.5 times greater, respectively (

5).

There are several possible explanations for why people with schizophrenia receive less health care. People with schizophrenia may have problems describing their medical symptoms to primary care physicians. Physicians may be uncomfortable treating people with schizophrenia (

23), possibly reflecting stigmatization of people with this disorder. Likewise, psychiatrists may not feel comfortable providing primary and preventive health care for their patients (

24). Finally, the health care system may treat people with schizophrenia differently than others. A pair of recent studies found that people with schizophrenia who have a myocardial infarction are less likely to receive cardiac catheterization and have a mortality rate 34 percent higher than that of people in the general population who suffer a myocardial infarction (

6,

25).

The findings of this study are supported by the inclusion of comparison patients who were matched for age and gender with the patients with schizophrenia. In addition, all patients were identified by the same mechanism—a review of the psychiatric clinic log. In addition, a single physician reviewed all the charts.

Among the limitations of this study are its retrospective design and its reliance on patients' reporting their symptoms and medical history and on the treating physicians' recording this information in the chart. The physician reviewing the charts was not blind to psychiatric diagnoses and had provided care to a small proportion (less than 20 percent) of the patients in the study. The homeless people in this study were living at the St. Vincent de Paul shelter, which provides a comprehensive array of medical and psychiatric services that are not available in many other homeless shelters. The health status and use of services by homeless people in shelters may be different from those among homeless people who do not use shelters.

The patients in the comparison group had a diagnosis of major depression. People with this diagnosis have been reported to have higher levels of health care utilization, higher health care costs (

26), and worse health outcomes (

27) than the general population. Another study found that patients with depression treated in a health maintenance organization had higher general medical costs than patients with bipolar disorder or no mental illness (

28). Thus the inclusion of patients with major depression as the comparison group in our study may have resulted in larger differences between groups in the amount of health care received than we would have observed with a comparison group of persons with no mental illness.

Several of the differences we found, including fewer medical visits and fewer diagnosed medical illnesses among patients with schizophrenia, probably reflect both less use of medical care by patients with schizophrenia and greater use by patients with depression. On the other hand, other measures we used, including whether a patient received specific components of the physical examination or laboratory screening tests, are likely to be less sensitive to greater use of health care services.

Future research on primary and preventive health care for people with schizophrenia should include comparison groups with no mental illness in addition to those with major depression. The samples were relatively small, and type I error due to multiple comparisons cannot be ruled out. Finally, some patients may have received health care at another clinic, although this is unlikely, given that the clinic at St. Vincent de Paul Village is free of charge, open during regular hours every day, and located within the shelter itself.

The current U.S. health care system can be difficult to navigate for the average person, and this difficulty is magnified for people with schizophrenia. Clearly, better methods of providing primary and preventive health care for people with schizophrenia need to be developed, studied, and implemented.