Few epidemiological studies of homeless populations focus on persons who are homeless for the first time. Male first-time users of homeless shelters have been studied in New York (

1) and Montreal (

2), and women who are homeless for the first time have been studied in Pennsylvania and California (

3). Studies of recent arrivals at homeless shelters in a Midwest city (

4) and the short-term nonchronically homeless persons in Florida (

5) have contrasted these individuals with the general homeless population. These studies provide some evidence of less severe illness and dysfunction among younger persons who are homeless for the first time, but there are also many similarities between this younger group and the larger group of homeless persons. Kuhn and Culhane (

6) complemented these investigations by presenting a typology for differentiating between persons who are episodically homeless and those who are chronically homeless.

What we do know about the short-term experience of first-time homeless persons is not encouraging. In a six-month follow-up study, Sosin and colleagues (

4) detected a pattern of intermittent homelessness: of 65 recent arrivals in homeless shelters, 80 percent exited from homelessness, but 60 percent of these become homeless a second time. In a study of 119 male first-time users of homeless shelters, Fournier and associates (

2) found that 25 percent either had remained homeless after a year or had returned to homelessness after exiting temporarily. These findings suggest that many people who are homeless for the first time will become homeless again.

This article is based on findings from a study in which users of homeless shelters in Toronto were interviewed during a 12-month period ending in July 1997 to identify characteristics of individuals who are homeless for the first time and to describe how these persons differ from those who have been homeless more than once.

Methods

The Pathways Into Homelessness project used both quantitative and qualitative interviews to estimate the prevalence of mental illness among homeless persons, to describe pathways into homelessness, and to identify areas for policy reform. A more complete outline of the project's approach, instrumentation, and methods has been published elsewhere (

7,

8), as have reports based on the qualitative findings (

9).

An episode of homelessness was defined as a lack of housing for at least seven nights in the previous month and no prospect of housing in the next month. Episodes of homelessness had to be more than one month apart to be counted as separate occurrences. This requirement ensured that contextual factors, such as limits on the duration of shelter stays, did not artificially increase the number of reported episodes of homelessness.

The sample was stratified by age, sex, level of shelter use, and type of shelter to match the proportions obtained from Toronto's Hostel Services database, which details the previous year's use of shelters by unaccompanied persons aged 18 years or older. Thus the sample reflected a population of more than 10,000 homeless individuals. In the larger population, days of shelter use differed significantly between persons who had stayed at a single shelter once during the year (defined as low use) and those who had had more than one stay either at the same shelter (medium use) or at two or more different shelters (high use). Thus our sample of first-time homeless persons was unlikely to include many persons with prolonged shelter stays.

In addition to a structured interview for diagnostic purposes, the study participants were asked questions that covered sociodemographic characteristics, employment and income history, legal problems, social support, history of homelessness, adverse life events, physical health, and service use. Measures of childhood background were based on the definitions of Koegel and colleagues (

10).

First-time homeless persons were defined as those who had not been homeless since the age of 18 years. Differences between groups were tested by using Pearson one-tailed chi square tests for categorical data and independent-sample t tests for continuous variables, with a significance level of .05.

Results

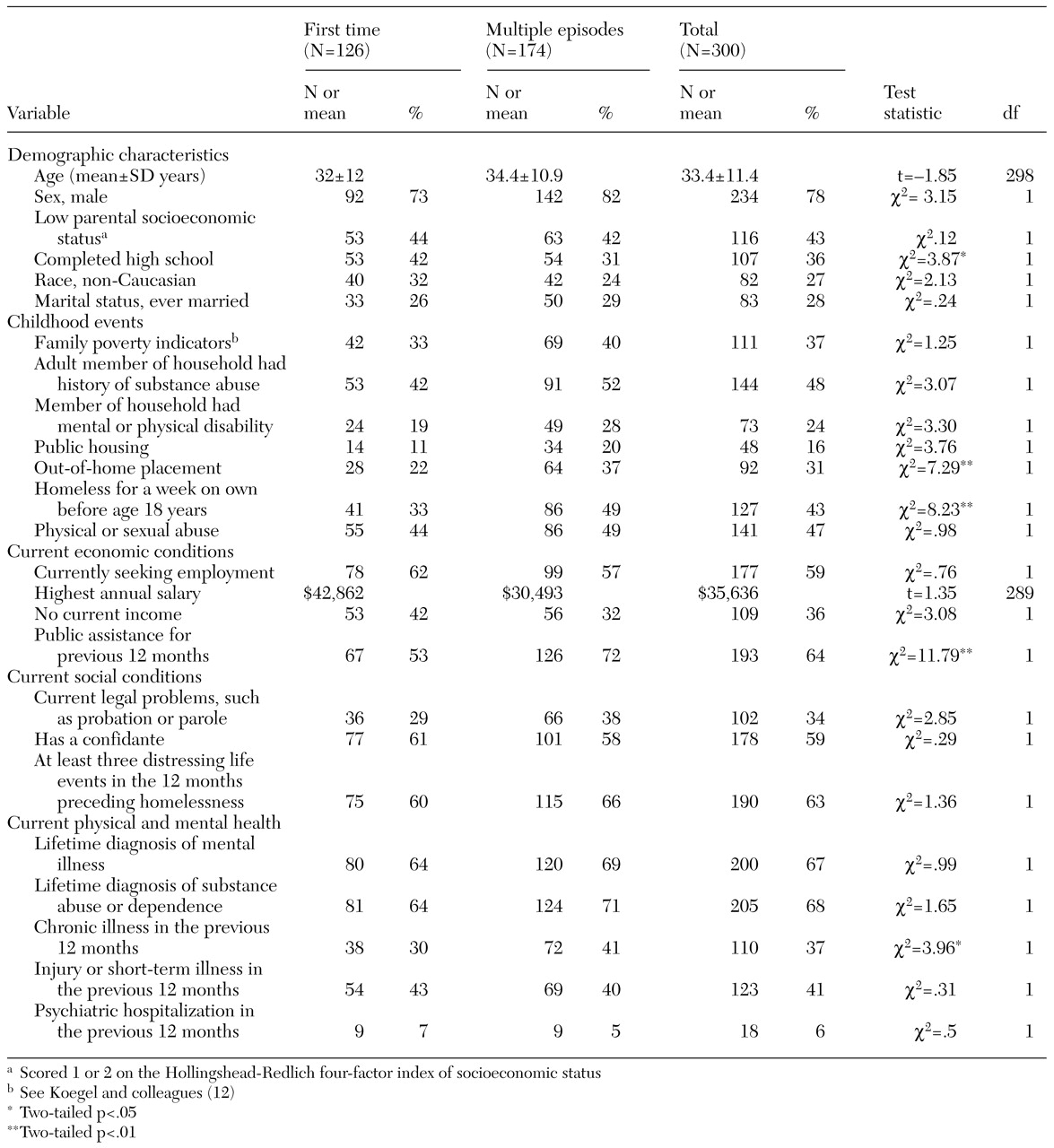

The characteristics of the sample are summarized in

Table 1. Both groups were predominantly male and had impoverished socioeconomic backgrounds with high rates of family history of mental illness and substance abuse. The two groups were differentiated by childhood events related to housing history. Those who had been homeless previously were more likely to have had an out-of-home placement (37 percent compared with 22 percent) and to have been homeless before the age of 18 years (49 percent compared with 33 percent). Childhood abuse was common in both groups.

In both groups, current life conditions included high rates of unemployment and absence of income other than public assistance. A larger proportion of first-time homeless persons had completed high school (42 percent compared with 31 percent). First-time homeless persons were also less likely to have received public assistance before becoming homeless (54 percent compared with 72 percent). Indicators of legal problems, social support (having a confidante), and distressing life events were similar between the two groups.

Lifetime substance abuse or dependence and rates of psychiatric hospitalization in the previous 12 months were also similar between the two groups. Those who had been homeless before were more likely to have chronic physical problems (41 percent compared with 30 percent).

Discussion

Persons who are homeless for the first time represent a sizable proportion of the overall population of homeless shelter users. Two-fifths of the homeless persons in this study had not been homeless before in their adult lives.

It is incorrect to assume that the first-time homeless represent a high-functioning group of individuals who are only temporarily dislocated and unlikely to return to shelters or the streets. We found more similarities than differences between those who were homeless for the first time and those who had been homeless before. No gender differences were noted, and in both groups there was evidence of social disadvantage as well as mental and physical illness. Rates of various psychiatric disorders did not differ between the two groups, and nor did rates of previous hospitalization. In contrast with most other studies, we found no differences in substance abuse between persons who were homeless for the first time and those who had been homeless before. First-time homeless persons have multiple indicators of serious problems and in many ways resemble their more chronically homeless counterparts.

The differences we found are not surprising, and all have been reported in at least one previous study. The finding that persons who had previously been homeless are likely to be receiving disability benefits and to have chronic physical problems indicates that this slightly older group has had more opportunity to experience multiple episodes of homelessness and illness and to obtain income supports with the passage of time. A lower educational level in the chronically homeless group reflects differences in human capital that are modifiable with appropriate rehabilitative interventions.

The results of this study suggest that certain childhood factors predispose individuals to more chronic homelessness. Poverty alone does not seem to be a predictive factor, but housing instability increases the risk of continued homelessness. Out-of-home placement and childhood homelessness have also been identified as predictors in previous studies (

3,

4,

5). Early experiences of not having a secure and stable place to live seem to make it harder over the long term to regain and maintain housing once it has been lost.

Conclusion

The results of this study underscore the importance of primary prevention strategies that target dysfunctional families to improve their housing stability. Few risk indicators identify target groups for secondary prevention strategies. Given the level of need that is evident among persons who are homeless for the first time, this group should receive appropriate services early. Such interventions must be tailored to meet a variety of needs given that this is not a homogeneous group.