Demand for proper health care has spawned a greater awareness of the role of ethnicity or race in the provision of appropriate mental health services for minority populations (

1). Until recently, research on the provision of mental health services did not consider race or ethnicity as a major factor (

2). However, when investigators examined the use of and expenditures for mental health services by Medicaid beneficiaries in New York, they found marked differences between ethnic groups (

3). These data, as well as the findings of other investigators (

4), have raised concerns about potential disparities in mental health care among racial and ethnic minorities.

Not all differences in rates of service use constitute disparities. Adjustment for "legitimate" sources of difference—such as need—is necessary for identifying inequities (

5). Further adjustment for the many factors that affect use, such as socioeconomic status, is necessary for identifying the inequity due to race or ethnicity (

6). The U.S. Surgeon General (

7) recently called attention to the limited understanding of cultural factors that may contribute to an inadequate allocation of and access to resources for appropriate treatment. The study reported here used data from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (

8)—a nationwide survey designed to provide information on the prevalence of

DSM-III-R disorders and the use of mental health services—to investigate whether there are inequalities in the rates of specialty care for Latinos and African Americans compared with non-Latino whites.

Some studies have indicated that Latinos experience great difficulties in obtaining adequate access to mental health services (

9,

10,

11) and are underrepresented in mental health care settings (

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17). Other studies have shown comparable levels of use of mental health services between Latinos and non-Latinos (

18,

19). Possible methodologic explanations for these divergent results are differences in the measures used to assess psychiatric disorders and service use (

20), response bias due to instrumentation (

21,

22), differences in geographic locations, and differences in measures of access to mental health services. The differences have also been attributed to the selection of covariates or to uncontrolled factors such as level of psychiatric morbidity (

23), insurance coverage (

24), and socioeconomic status.

We explored multiple factors that may contribute to ethnic or racial disparities in the use of mental health services. What role does ethnicity or race play compared with other components of social position, such as income and wealth or the environmental context, in explaining differential rates of specialty care use? Substantial evidence indicates that social position plays a major role in psychiatric disorders (

25) and service use (

26,

27). Similarly, the environmental context is crucial in the variations in health and access to health care (

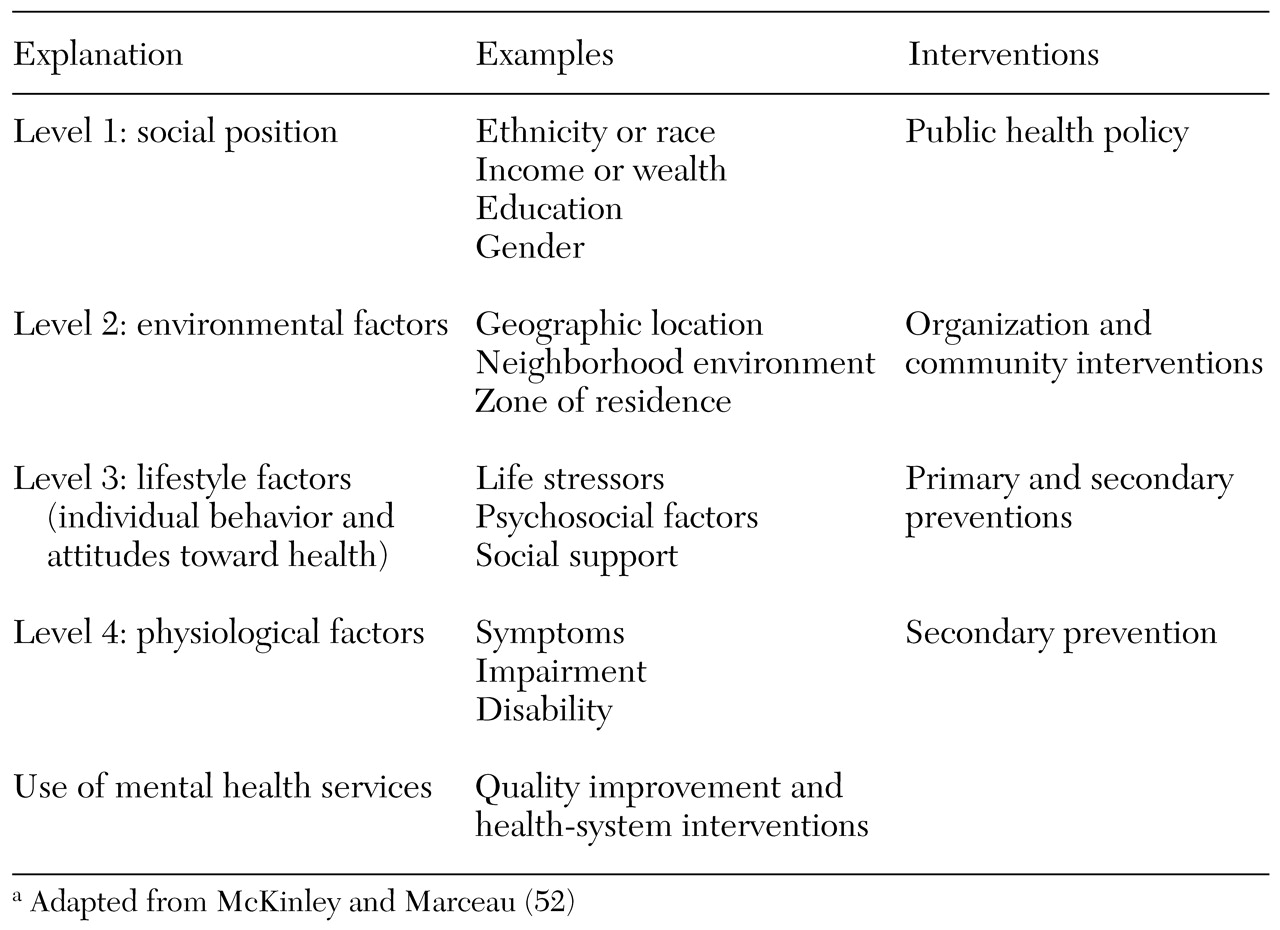

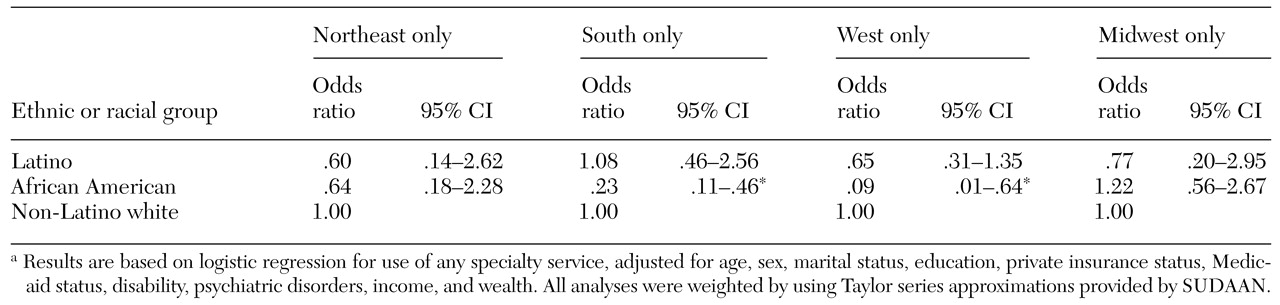

28). These factors can help clarify links to ethnic or racial differences in service use, illustrated in

Table 1. Therefore, we first compared estimated rates of use of specialty care services by ethnic and racial groups, adjusting for psychiatric disorder, insurance status, and socioeconomic status. Second, we evaluated the association between ethnic and racial group and differential rates of specialty care, stratifying by poverty status and by geographic location.

Methods

Study population and data

We used data from the 1990-1992 NCS (

29), based on a probability sample of 8,098 English-speaking respondents in the United States aged 15 to 54 years. The study methods have been described previously (

30,

31,

32). Although the NCS was not designed to provide an understanding of racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services, it does provide comparative data for African Americans, Latinos, and non-Latino whites, all based on the same methods and research design.

Ethnic and racial identification

Respondents were asked to self-identify whether they were of Spanish or Latino descent and, if so, to indicate their nationality—Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or other Spanish. Persons who identified themselves as being of Latino descent, independent of how they reported their race, were categorized as Latino (N=695). Overall, there were 432 Mexican Americans, 67 Puerto Ricans, 30 Cubans, and 166 other Latinos. Nonetheless, the small size of the Latino sample prevented us from conducting subgroup analyses. Respondents who did not identify themselves as being of Spanish or Latino descent were asked to identify themselves as white, black, American Indian, Asian, or other. Respondents who classified themselves as non-Latino white (N=6,026) or African American (N=987) were also included in the analysis.

Use of outpatient mental health services

Any use of outpatient mental health services in the previous year was defined as speaking to a professional about symptoms or disorders in the 12-month period before the interview (

32). Treatment for a mental health problem by a physician other than a psychiatrist or treatment in a hospital emergency department or a doctor's private office was defined as general medical care. Specialty mental health care was defined as treatment by a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or a psychotherapist or treatment by any professional in a specialty mental health setting. Mental health care provided in a social service agency or department was coded as human service- sector care.

Social position, geographic location, and zone of residence

No consensus exists about how social position is best operationalized, but—however defined—this variable shows a robust relationship to psychiatric illness and service use (

26,

33,

34). Social position was based on the respondent's estimate of household income from all sources before income tax deductions and wealth. Income was coded in four categories: $0 to $14,999, $15,000 to $34,999, $35,000 to $69,999, and $70,000 or more. Wealth was defined as the total funds of the respondent and his or her spouse or partner in checking and saving accounts, stocks, bonds, real estate, and house value net of any mortgage. Wealth was coded in three categories: less than $10,000, $10,000 to $99,000, and $100,000 or more. Poverty status was determined by dividing the family income data into poor (less than $15,000) and nonpoor ($15,000 or more). This categorization is based on Census Bureau income thresholds for 1990-1992. The poverty threshold for a four-person household was $13,400 to $14,400 (

35); therefore, a threshold of less than $15,000 was used to designate poverty in our sample. Geographic location was coded as Northeast, South, West, and Midwest. Zone of residence was coded as urban or rural.

Demographic characteristics, insurance status, and psychiatric morbidity

Several demographic variables that have previously been found to be correlated with use of mental health services (

36,

37) were included as controls: sex, age, marital status, education, and insurance status. Sex was a dichotomous variable, with female as the reference category. Age was included as either a categorical variable (15 to 24 years, 25 to 34 years, 35 to 44 years, and 45 years or older) or as a continuous variable. Marital status was categorized as disrupted marriage (for example, separated, divorced, or widowed), never married, or married. Education was included as a continuous variable of the number of years of education or as a categorical variable (less than high school, high school, 13 to 15 years, and 16 years or more). Insurance was represented by two dichotomous variables: private insurance other than Medicaid and Medicaid, with no insurance as the reference category.

Previous research has established a strong association between the presence and severity of psychiatric morbidity and the use of mental health services (

17). Therefore, we examined how differences in psychiatric morbidity might influence ethnic and racial differences in service use. Psychiatric morbidity was constructed as a four-category variable: two or more diagnoses in the previous year, one diagnosis in the previous year, any lifetime diagnosis, and no lifetime diagnosis. Diagnoses of mental disorders were determined by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

38) using

DSM-III-R criteria. The CIDI generates diagnoses of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders with good reliability and validity (

39). Disability was measured by asking respondents to report the number of days in the previous 30 days that they either cut down on or were unable to perform usual activities because of mental illness. Disability was recorded for respondents who reported one or more such days.

Analyses

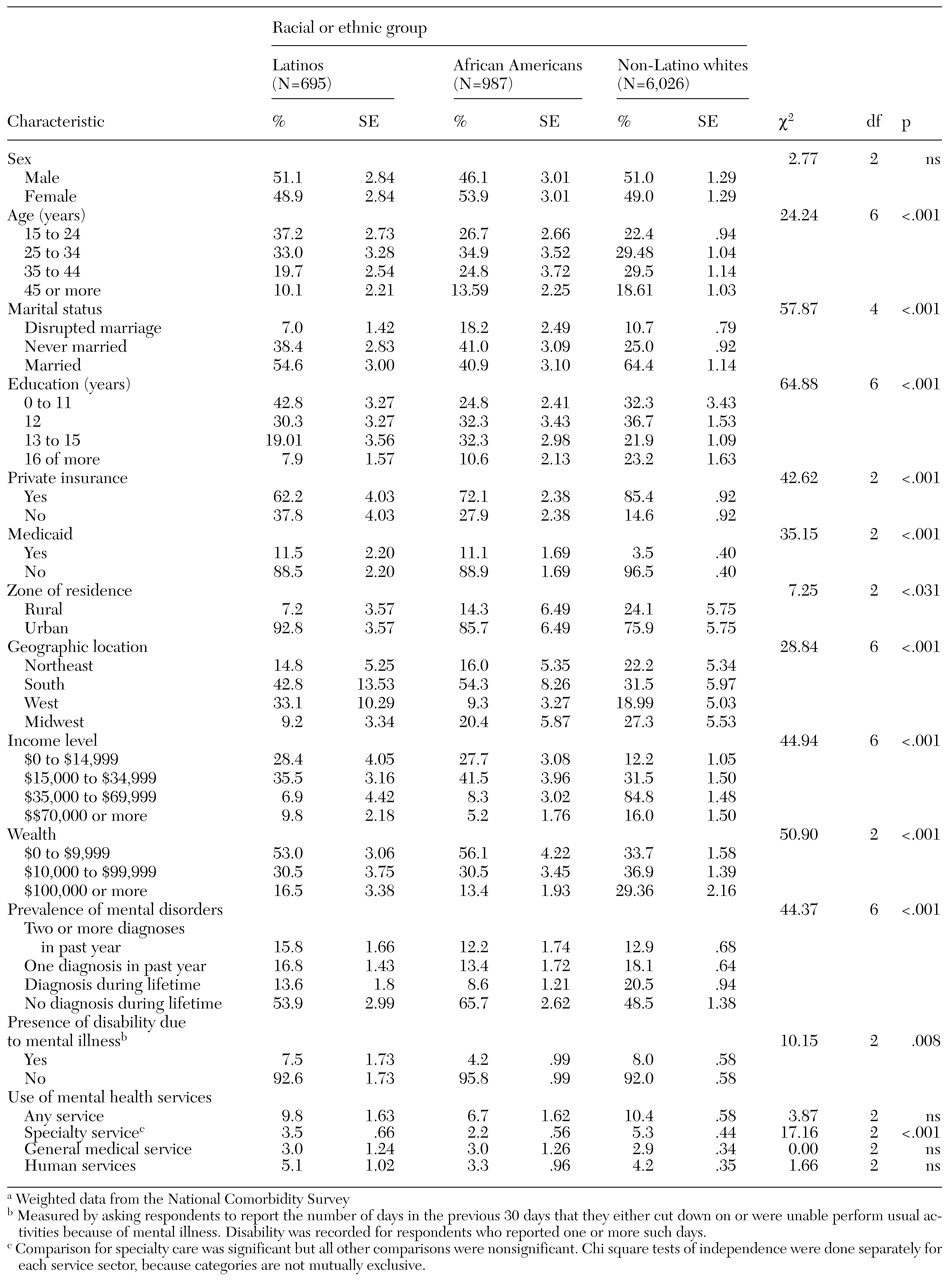

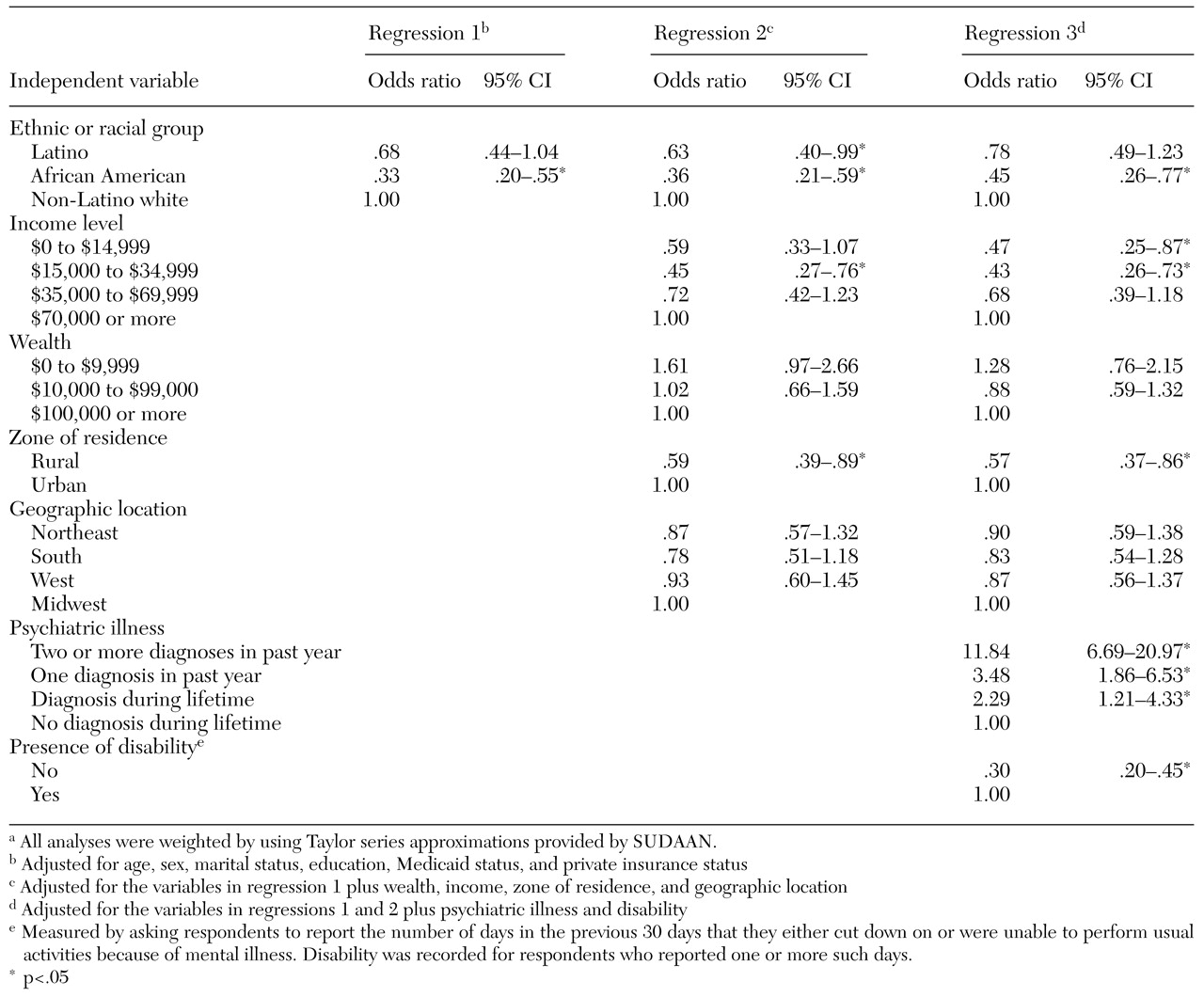

Comparisons of the distributions of demographic characteristics, insurance status, psychiatric morbidity, zone of residence, geographic location, income, and use of mental health services across ethnic groups were made by using chi square tests. Differences in service use were apparent only in the use of specialty services; therefore, all subsequent analyses used specialty care as the dependent variable. Logistic regression analyses examined the positive correlations between ethnic or racial group and use of specialty care with adjustment for demographic and insurance variables.

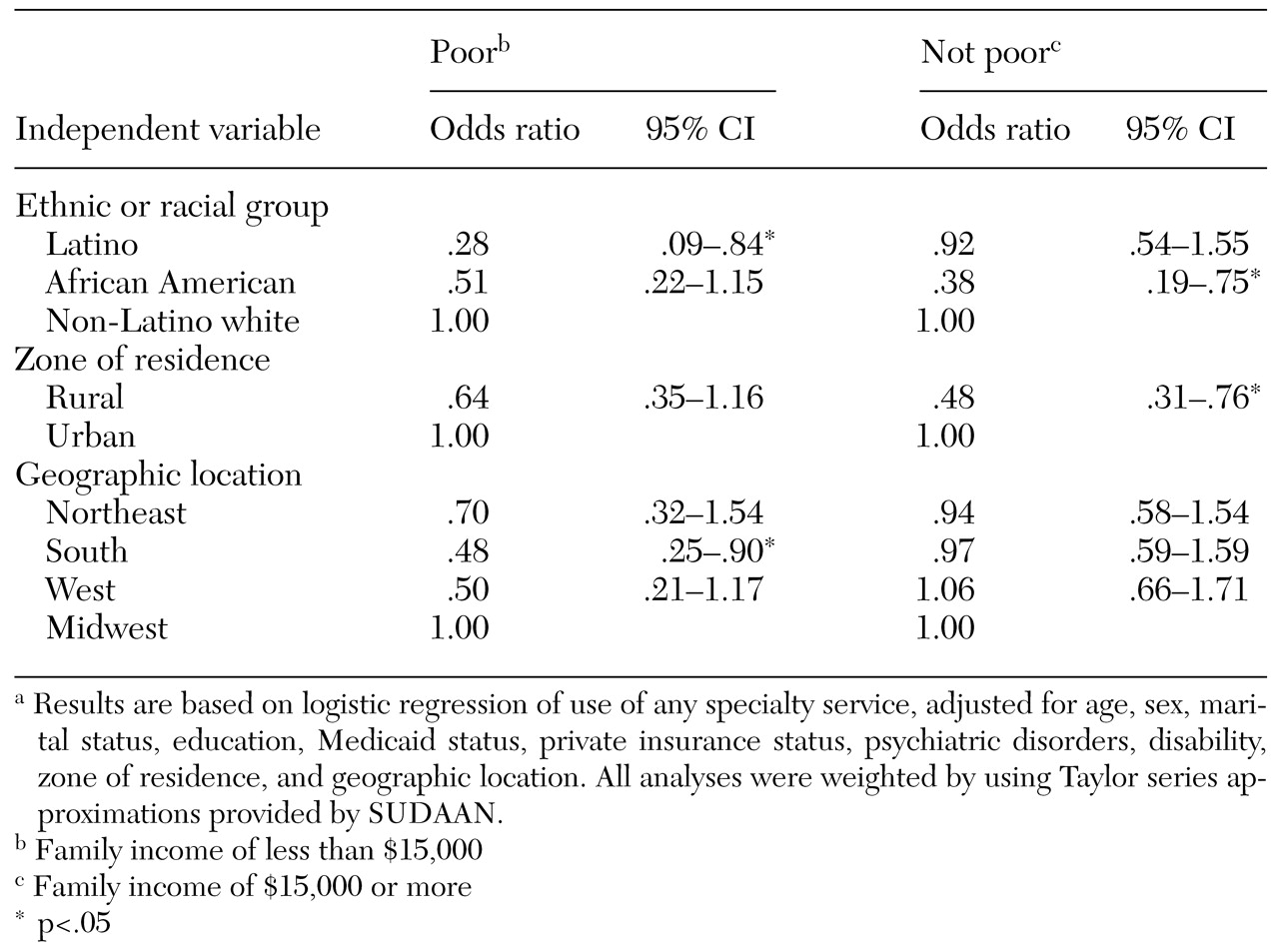

A second set of analyses was conducted to assess the relationship between ethnic or racial group and use of specialty care after adjustment for social position, geographic location, and zone of residence. To better understand the association between ethnicity and the use of specialty care, a third logistic regression was computed that added to the model two additional covariates: psychiatric illness and disability. We also conducted separate logistic regressions stratifying the sample by poverty status and by geographic location. The standard errors of the estimates and the logistic regression coefficients were calculated by using SUDAAN (

40) to adjust for clustering and nonresponse in the sample design.

Discussion

The lower level of access to specialty mental health care among poor Latinos compared with poor non-Latino whites is consistent with the results of other published studies (

4,

33,

41). At least five factors could explain differences in use of specialty services between poor Latinos and poor non-Latino whites: language fluency, cultural differences such as self-reliance, access to Medicaid specialty services in Latino neighborhoods, differences in recognition of mental health problems, and lower quality of mental health care. Even though the NCS was limited to English-speaking respondents, many poor Latinos may not be fluent enough in English to feel comfortable discussing their mental health problems or participating in psychotherapy.

Previous studies have shown that psychiatric patients with limited English proficiency underutilized specialist outpatient services and that those who did receive such services were less likely to participate in psychotherapy than fluent English speakers (

42). We speculate that limited English proficiency among poor Latinos in our study may have contributed to their lower use of specialty services compared with poor African Americans or whites with no linguistic barriers. If a patient with limited English proficiency cannot gain access to a bilingual provider, he or she may not seek specialty care.

A second factor may be self-reliance among poor Latinos. Self-reliance in dealing with mental health problems, a coping mechanism more commonly observed among Latinos than whites (

43), reduces the use of mental health services (

44). A third factor might be the access to Medicaid specialty services in Latino neighborhoods compared with neighborhoods where poor non-Latino whites live. Research has found that the more behavioral health specialists there are in a community, the more likely individuals are to use these services (

45).

In one study, lack of recognition of mental health problems might also account for differences in use of specialty care. Differences in the use of mental health services between persons in Canada and persons in the United States (mostly non-Latino whites) were not significant after perceived need for mental health care was controlled for (

46). This finding suggests that ethnic or racial differences in perceived need for care might explain lower rates of care.

Another explanation for the lower rates of specialty care among poor Latinos than among poor whites might be previous experience with lower-quality mental health care. In a recent study, only 24 percent of Hispanic persons with anxiety and depression received appropriate care (

47), which suggests that Latinos may perceive that they have less to gain from the mental health care system.

Our findings that African Americans who were not categorized as poor were less likely to use specialty services than their white counterparts, even after adjustment for demographic variables, insurance status, and psychiatric morbidity, is supported by the results of other research (

48). African Americans appear to have fewer financial resources than whites in any income bracket and may experience the modest cost sharing associated with private insurance as more of a burden than whites (

49). Crude control for insurance might not eliminate the differences in the insurance benefits between African Americans and whites categorized as not being poor.

Another possible explanation for the differences we observed is greater mistrust among patients; African Americans have experienced racism and mistreatment by the health care system (

50), which may discourage them from seeking specialty care. In a nationwide study, 35 percent of African Americans stated that racism was a major problem in health care, compared with only 16 percent of whites (

51).

In addition, regional variations in the receipt of specialty care by ethnic and racial minorities suggest policy or system factors as topics for research. Whether these regional differences are functions of geographic location rather than different levels of availability of particular minority providers in different communities cannot be determined from the NCS data. Thus it is impossible to clarify whether eligibility policies in the South make it less likely for African Americans than for non-Latino white to obtain care or whether the difference is due to the availability of minority providers or health care system factors—for example, referrals and reimbursement procedures. Distribution of specialty facilities that serve African Americans in the South compared with those that serve non-Latino whites may account for differences in access to specialty care.

Our results are consistent with McKinlay's framework (

52), which supposes that the combined effect of poverty and minority status places a person at a higher risk of reduced access to mental health services. Our findings suggest that the effect of minority status on use of specialty care services may vary depending on poverty status and geographic location. The importance of stratification underlines how the effects of ethnicity or race, poverty, and geographic region need to be analyzed in combination. In terms of specialty care use, being African American has less of an impact among poor persons than among those who are not poor, whereas the opposite is true for Latinos. Thus the effects of ethnicity and race should not be examined alone but in terms of how they interact with poverty and region.

The fact that the magnitude of the association between ethnicity and the use of specialty services did not substantially change after adjustment for psychiatric morbidity and other covariates suggests that ethnicity and race may be a component of a more complex construct of social position. Subjective social class, perceived placement in the community, and relative deprivation may all be important variables—not measured in the NCS study—that, in addition to race, income, and wealth, define a person's social position. Furthermore, income can be confounded by other dimensions of health that were not measured in this study (

53). More detailed information about environmental context is also required for modeling the effects of the neighborhood—for example, the neighborhood's environment and cohesion. Such information portrays commonly held views about life that may affect psychiatric illness and pathways to treatment.

This study had several limitations. The NCS study was conducted in the pre-managed care era, so there are no data on how the results of our study might vary under newer health care organization and financing structures. In addition, the cross-sectional design of the study makes it difficult to establish the causal pathways of differential rates of use of specialty services among different ethnic and racial minorities. Selective migration to geographic regions where specialty services are not easily accessible could explain some of the observed ethnic or racial differences. The exclusion of other social and lifestyle factors that were not available in the data set could also change the strength of the correlations with some of the independent variables. Furthermore, some of the observed results may have been due to measurement error in ethnic and racial data (

54).

Operationalization of the constructs of race or ethnicity in the NCS follows a crude approach. The survey merely asks respondents to indicate their race or ethnicity by choosing from one of several response options, which might be arbitrary depending on the types and number of categories provided (

55). The conceptual validity of these constructs has been challenged (

56).

Another limitation of the NCS is that all interviews were conducted in English. Latino, Spanish-speaking, monolingual respondents were effectively excluded from the survey. This bias might have served to underestimate the effects of ethnicity or race on use of specialty services, if we assume that these ethnic minorities are less likely to seek care as a result of increased barriers, such as language barriers, lack of knowledge about how to navigate the service sectors, and undocumented immigration status.